HEALTHY COMMUNITIES Legislative Comparison Survey Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Largest Annual Gathering of Planners in PA! WE SHARE YOUR GOALS for COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

PLAN on ERIE American Planning Association Pennsylvania Chapter CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENT 2018 Annual Conference APA PA2018 this year! • 400 Planners expected! • 40 Classroom sessions • 6 Mobile workshops offered • Up to 12.25 CM credits, including Law and Ethics • Making a return, Fast – Fun – Fervent showcasing multiple presenters, multiple topics, seven minutes each • Welcome Reception at Erie Maritime Museum • “Intentionality: Competing in the 21st Century” Opening Keynote Session by Tom Murphy, Urban Land Institute • Annual Awards presentation – our best and brightest • S tate of the APA-PA Chapter • Monday reception with the Exhibitors • “The Neighborhood Play Book: Community Engagement” Plenary by Joe Nickol and Kevin Wright, Yard and Company • “Infrastructure Crisis: It’s Time to Rethink our Approach to Growth” Pitkin Lecture by Charles Marohn, PE, AICP, Strong Towns • Tuesday afternoon Desserts with our Exhibitors • NEW THIS YEAR! Erie Networking Lounge PA Chapter of the American Planning Association 2018 Annual Conference Sunday, October 14 – Tuesday, October 16 Erie, PA #APAPA18 The largest annual gathering of Planners in PA! WE SHARE YOUR GOALS FOR COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Paseo Verde in Philadelphia was funded in part by Low-Income Housing Tax Credits from PHFA Affordable home loans since 1982 www.PHFA.org 855-827-3466 Tom Wolf, Governor Brian A. Hudson Sr., Executive Director & CEO 2018 Annual Conference PA Chapter of APA |3 Get all the conference details at www.planningpa.org YOURGUIDE Conference At A Glance 5 Many Thanks -

Healthy Rural Community Design: a Scorecard for Comprehensive Plans

Healthy Rural Community Design: A Scorecard for Comprehensive Plans Version 3.1.1 Suggested citation: Charron, Lisa. Healthy Rural Community Design: A Scorecard for Comprehensive Plans – Version 3.1.1. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute; 2018. Funding to develop this tool was provided through a grant from the Wisconsin Partnership Program, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin- Madison. We value your feedback! Please visit https://www.wihealthatlas.org/comprehensive- plans/ to complete a short survey about your experience using the tool so that we can make future versions even better! The web page also has a link to sign up for email updates about new versions of the tool. Design modified from “Gertrude” template, slidescarnival.com. Photo credits, all via Flickr creative commons: Cover photo: Suzie’s Farm Facing photo: Daniel Feivoir Facing photo next page: David Clow 2 Table of contents Introduction Creating the Healthy Rural Community Design tool 4 About the tool 4 Helpful tips and resources 5 How do I know if my community is rural? 5 Scoring methodology 5 Plan evaluation process 7 For researchers 7 The Scorecard A. Overall plan, vision, and strategy 8 B. Healthy living 1) How we move around and access services 10 2) How we eat and drink 16 3) How we play and get our exercise 18 C. Active design 20 References 24 Appendix A: Scoresheet 26 3 Creating the Healthy Rural About the tool Community Design tool This scorecard is meant to help rural planners, puBlic health advocates, and community members The Healthy Rural Community Design Scorecard was recognize planning policies, strategies, and visions developed as part of the University of Wisconsin- within their local comprehensive plans that promote Madison's OBesity Prevention Initiative (OPI). -

WOMEN SEEKING FACULTY POSITIONS in Urban and Regional

2015 FWIG CV Book WOMEN SEEKING FACULTY POSITIONS in Urban and Regional Planning Prepared by the Faculty Women’s Interest Group (FWIG) The Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning October 2015 Dear Department Chairs, Heads, Directors, and Colleagues: The Faculty Women’s Interest Group (FWIG) of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning (ACSP) is proud to present you with the 2014 edition of a collection of abbreviated CVs of women seeking tenure-earning faculty positions in Urban and Regional Planning. Most of the women appearing in this booklet are new PhD’s or just entering the profession, although some are employed but looking for new positions. Most are seeking tenure-track jobs, although some may consider a one-year, visiting, or non-tenure earning position. These candidates were required to condense their considerable skills, talents, and experience into just two pages. We also forced the candidates to identify their two major areas of interest, expertise, and/or experience, using our categories. The candidates may well have preferred different categories. Please carefully read the brief resumes to see if the candidates meet your needs. We urge you to contact the candidates directly for additional information on what they have to offer your program. On behalf of FWIG we thank you for considering these newest members of our profession. If we can be of any help, please do not hesitate to call on either of us. Sincerely !Dr. J. Rosie Tighe Dr. K. Meghan Wieters Editor, 2014 Resume Book President, FWIG! [email protected] -

Planning & Zoning for Health in the Built Environment

PAS EIP-38 November 2016 T Planning & Zoning for Health in the Built Environment The Planning Advisory Service (PAS) researchers are pleased to provide you with information from our world-class planning library. This packet represents a typical collection of documents PAS provides in response to research inquiries from our subscribers. For more information about PAS visit www.planning.org/pas. PAS Essential PAS INFO PACKE INFO EIP-38 Planning & Zoning for Health in the Built Environment This Essential Info Packet was supported through a cooperative agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Copyright © 2016 American Planning Association 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200, Chicago, IL 60601-5927 1030 15th St., NW, Suite 750 West, Washington, DC 20005-1503 www.planning.org/pas ISBN: 978-1-61190-189-4 EIP-38 Planning & Zoning for Health in the Built Environment Contents Foreword I. Background: The Connections Between Health and the Built Environment Big-picture planning-focused reports that make the case that the built environment can impact health II. Clearinghouses and Websites on Planning for Health in the Built Environment Websites that offer collections of resources on health in the built environment III. Data Sources for Health in the Built Environment Sources of data for planners on health in the built environment IV. Collaborating with Local Public Health Agencies and Officials Information and guidance on planner–public health official collaboration V. Health Impact Assessments Resources focusing on Health Impact Assessments VI. Toolkits and Model Documents on Planning for Health in the Built Environment Guidance for planners on general planning for health strategies and implementation VII. -

BUILDING HEALTHY COMMUNITIES by Dr

BUILDING HEALTHY COMMUNITIES by Dr. Howard Frumkin, M.D., Dr. P.H., Director National Center for Environmental Health Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Have you ever thought about how the way we design and build our communities can affect our health? You’ve just seen some examples of both positive and negative community design. You saw parks where people can get regular exercise. You saw sidewalks where people can walk to the places they need to routinely go and keep physically active. But you also saw some dangerous pedestrian crossings where people take their lives in their hands. You saw traffic jams where people may sit for hours becoming angry and breathing dangerous fumes. I’m Dr. Howard Frumkin, Director of the National Center for Environmental Health and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. We’re here to talk about how community design can either protect or threaten our health. This is not a new concept. From the earliest days of our ancestors living in caves, they must have known that some places were healthier than others. A dangerous cave could be a cave with moisture, with too much smoke from fires, or with varmints. Much later when our ancestors moved into cities and towns, some cities and towns were healthier than others based on the supply of fresh water, treatment of sewage, and the way they handled their waste materials. Next we came to the industrial revolution a couple of centuries ago, and as factories located in towns, the results were sometimes pretty negative. -

Healthy Community Design

Statutory Authorization: 24 V.S.A. §§ 4302, 4382, 4410, 4430, 4432 Type: NONREGULATORY & REGULATORY Related Topic Areas: Bicycle & Pedestrian Facilities; Capital Improvement Program; Downtown Revitalization; Facilities Management; Growth Centers; Land Use & Development Regulations; Open Space Programs; Open Space Regulations; Roads & Highways; Public Transit; Development Healthy Community Design B 2YHUYLHZ Planners, in collaboration with public health advocates, are returning to our roots by intentionally designing communities to promote public health, safety, and welfare. Community health–once the primary purpose for planning and zoning– became an afterthought in our design of built environments to better accommodate cars than people. Healthy community initiatives nationally, and here in Vermont, are once again bringing public health considerations to the fore, by re- establishing community health as a contemporary, increasingly relevant reason for good community design. This topic paper supplements and draws from the more comprehensive Vermont Healthy Community Design Farmers markets in villages and downtowns where people can walk to Resource: Active Living and Healthy pick up groceries help to promote both physical activity and access Eating, issued by the Vermont Health to healthy, locally-grown food. Photo by Lee Krohn Department. Health advocate interest in planning and community DUHVLJQLÀFDQWFRQWULEXWRUVWRULVLQJ organizations – including faith- design stems from growing concern rates of obesity, diabetes and the EDVHGQRQSURÀWDQGVRFLDOJURXSV about the rising rates of chronic persistence of chronic diseases. The – to promote healthy behavior. illness in modern society. Unhealthy Vermont Health Department’s “Fit eating habits and sedentary lifestyles and Healthy Vermonters” initiative Decisions made by government, targets obesity prevention by focusing businesses, and institutions all on ways to increase physical activity have an important impact on The way a community is and improve healthy eating. -

Healthy Community Design Toolkit: Leveraging Positive Change

Healthy Community Design Toolkit— Leveraging Positive Change “We ought to plan the ideal of our city with an eye to four considerations. The first, as being the most indispensible, is health.” Aristotle, Politics Preface After less than a year in circulation, the “Healthy Community Design Toolkit—Leveraging Positive Change” is ready for a second edition. Responding to input from Mass in Motion partners, we have revised this edition to improve usability and to add a new focus on healthy aging throughout the report. The focus on healthy aging accomplishes two goals. First, it provides a window into how the toolkit can be used to address the specific needs of a population. This example will provide a replicable model for thinking through how to link a population’s healthy living needs with specific community design leverage points. Second, meeting the needs of older adults will take communities a long way toward meeting the needs of their full populations. The needs of older adults are, in many ways, not unique; it is more a question of degree than difference. For example, while a younger couple may be physically able to navigate a narrow sidewalk that is cracked and slippery, they will have a more enjoyable and safer walk on a sidewalk that has smooth, high-grip pavement, a wide unobstructed area for walking abreast, and curb ramps that lead directly to crosswalks. The new material on healthy aging is located throughout this version of the report. Look for boxes and sections labeled “Focus on Aging.” Thank you for using the Healthy Community Design Toolkit: Leveraging Positive Change. -

Healthy Community Design: Integrating Physical Activity And

An Analysis of State Health Impact Assessment Legislation By Doug Farquhar William T. Pound, Executive Director 7700 East First Place Denver, CO 80230 (303) 364-7700 444 North Capitol Street, N.W., Suite 515 Washington, D.C. 20001 (202) 624-5400 May 2014 The National Conference of State Legislatures is the bipartisan organization that serves the legislators and staffs of the states, commonwealths and territories. NCSL provides research, technical assistance and opportunities for policymakers to exchange ideas on the most pressing state issues and is an effective and respected advocate for the interests of the states in the American federal system. Its objectives are: To improve the quality and effectiveness of state legislatures. To promote policy innovation and communication among state legislatures. To ensure state legislatures a strong, cohesive voice in the federal system. The Conference operates from offices in Denver, Colorado, and Washington, D.C. This report summarizes state legislation and statutes that addresses healthy community design. This report is the property of the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) and is intended as a reference for state legislators and their staff. NCSL makes no warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for third-party's use of this information, or represents that its use by such third party would not infringe on privately owned rights. Printed on recycled paper © 2014 by the National Conference of State Legislatures. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-58024-___-_ NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgments PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is supported by the Health Impact Project, a collaboration of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts. -

Green Health: Building Sustainable Schools for Healthy Kids

Green Health BUILDING SUSTAINABLE SCHOOLS FOR HEALTHY KIDS A Workshop Co-sponsored by the National Collaborative for Childhood Obesity Research and the National Academy of Environmental Design In partnership with the U.S. Green Building Council Center for Green Schools Instead, environmental factors that influence when, where, and how much people eat and drink and how physically active they are must be engaged at a population scale to promote healthy behaviors. Introduction Role of Research indicates that environmental design at multiple spatial scales, Environmental from regional land use patterns to aspects of interior or graphic design, can Design within influence social norms and default behaviors related to dietary choices and daily physical activity. Development and dissemination of multidisciplinary Childhood Obesity environmental design research focused on childhood obesity prevention offers Prevention the potential for a valuable suite of new health promotion tools. However, successful at-scale implementation of health-oriented built environment A growing body of evidence clearly design strategies will depend on collaboration between public health and the demonstrates that alterations in design and building industries. One clear opportunity for building such a partnership lies in the many synergies individual behaviors alone are not between the environmental design objectives of childhood obesity prevention and those of the sustainability/green building movement. Focusing on sufficient to change the course of shared goals, such as community design that reduces automobile reliance and promotes active transportation, offers the prospect of a coordinated “Green the childhood obesity epidemic. Health” approach to built environment-oriented research. This is an attractive prospect given the growth and influence of non-profit advocacy groups such as Contents the U.S. -

Municipal Strategies to Increase Food Access Toolkit

Municipal Strategies to Increase Food Access Volume 2 of the Heathy Community Design Toolkit Acknowledgments This report was the result of collaboration between Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), Pioneer Valley Planning Commission, Metropolitan Area Planning Council, Massachusetts Association of Health Boards (MAHB), and Massachusetts Municipal Association. It was supported by funding from Mass in Motion and MAHB in partnership with MDPH, including by funds made available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office for State, Tribal, Local and Territorial Support, under B01OT009024. The conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of or endorsement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Numerous people and organizations contributed ideas, resources and information to the development of this report, and/or reviewed it and offered comments. We thank them all. Image Credits Cover: Flickr user Olearys Page xviv: Flickr user Jonathan Page 7: The Food Project Page 30: Flickr user Jules Page 45: Flickr user Cookbookman17 Page 52: Flickr user Stuart Webster Page 73: Flickr user William Warby Page 87: Flickr user Cookbookman 17 Page 105: Flickr user Cookbookman 17 Introduction Introduction This edition of the Healthy Community Design Toolkit—Leveraging Positive Change adds a focus on municipal strategies to facilitate food access in Massachusetts. Food access is increasingly being understood as playing -

Resource Guide for Healthy Community Planning Framing Questions and Links to Data

WASHINGTON APA’S GAME CHANGING INITIATIVE HEALTH AND PLANNING WORKING GROUP RESOURCE GUIDE FOR HEALTHY COMMUNITY PLANNING FRAMING QUESTIONS AND LINKS TO DATA Contributing Members Alyse S. Nelson, Amalia Leighton, Amy Pow, Andrea Petzel, Elizabeth Chamberlain, Joe Laxson, Julia Walton, Julie Bassuk, Lilith Yanagimachi (Brinkerhoff), Susan Lauinger Cover Graphic and Report Layout Rachel Miller, Kristina Tews Health and Planning Working Group Big Ideas Initiative The Washington American Planning Association’s (APA’s) Game Changing Initiative intends to help planners bring about far-reaching and fundamental change around our state’s most critical challenges. This Initiative is organized around Ten Big Ideas, which include addressing climate change, rebuilding infrastructure, protecting ecosystems, growing economies, and supporting sustainable agriculture. Planning to improve community health is one of the Ten Big Ideas. The Health and Planning Working Group believes planners could benefit from resources to start a conversation with decision-makers, build support, and jump start efforts to incorporate health into planning. To this end, the Working Group has developed a user-friendly resource guide to make it easier for planners to incorporate health considerations into their work. INTRODUCTION The following pages contain a series of framing questions and corresponding links to resources. Each question is from the perspective of a planner wanting to incorporate health into planning. This section also includes a few case study examples and messaging ideas, which outline possible talking points when communicating the importance of health in planning. Framing Questions 1. Why should my community incorporate health into planning? 2 2. How should I begin? What data should I gather and how can I track progress? 3 3. -

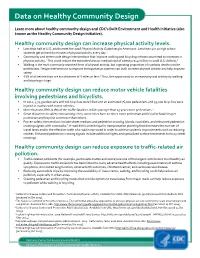

Data on Healthy Community Design �

Data on Healthy Community Design � Learn more about healthy community design and CDC’s Built Environment and Health Initiative (also known as the Healthy Community Design Initiative). Healthy community design can increase physical activity levels. • Less than half of U.S. adults meet the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Less than 3 in 10 high school � students get at least 60 minutes of physical activity every day.1 � • Community and street scale design interventions that improve walking and bicycling infrastructure lead to increases in physical activity.2 This could reduce the estimated annual medical cost of obesity ($147 billion in 2008 U.S. dollars).3 • Walking is the most commonly reported form of physical activity, but a growing proportion of roadway deaths involve pedestrians. Design interventions to improve transportation systems can both increase physical activity and help improve safety. • 43% of all vehicle trips are for distances of 3 miles or less.4 Thus, the opportunity to increase physical activity by walking and bicycling is huge. Healthy community design can reduce motor vehicle fatalities involving pedestrians and bicyclists. • In 2012, 4,743 pedestrians and 726 bicyclists were killed and an estimated 76,000 pedestrians and 49,000 bicyclists were injured in crashes with motor vehicles. • More than one-fifth (22%) of the traffic fatalities in kids younger than 15 years were pedestrians.5 • Great disparities in safety exist among cities; some cities have 10 times more pedestrian and bicyclist fatalities per � pedestrian and bicyclist commuter than others. � • Proven safety interventions include street medians and pedestrian crossing islands, road diets, and enhanced pedestrian crossing signals with crosswalks.6 A road diet is a technique in transportation planning that decreases the number of travel lanes and/or the effective width of a road is narrowed in order to achieve systemic improvements such as reducing crashes.