Band of Sisters Book Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cahier Des Charges De La Garde Ambulanciere

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE LA GARDE AMBULANCIERE DEPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME Document de travail SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ............................................................................................................................. 2 ARTICLE 1 : LES PRINCIPES DE LA GARDE ......................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2 : LA SECTORISATION ........................................................................................... 4 2.1. Les secteurs de garde ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Les lignes de garde affectées aux secteurs de garde .................................................... 4 2.3. Les locaux de garde ........................................................................................................ 5 ARTICLE 3 : L’ORGANISATION DE LA GARDE ...................................................................... 5 3.1. Elaboration du tableau de garde semestriel ................................................................... 5 3.2. Principe de permutation de garde ................................................................................... 6 3.3. Recours à la garde d’un autre secteur ............................................................................ 6 ARTICLE 4 : LES VEHICULES AFFECTES A LA GARDE....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 5 : L'EQUIPAGE AMBULANCIER ............................................................................. 7 5.1 L’équipage ....................................................................................................................... -

Vive Les Vacances !

LA VIE ET LES CHRÉTIENS EN HAUTE-SOMME ATHIES HAM NESLE JUILLET 2019 JUILLET E N° 29 TRIMESTRIEL - 1,25 - TRIMESTRIEL VIVE LES VACANCES ! PROCHAIN NUMÉRO SEPTEMBRE 2019 SECTEUR / P5 SECTEUR / P15 SECTEUR / P16 Mgr Leborgne, Pour la Noël au balcon, vice-président des biodiversité Pâques en camps évêques de France 450 HORAIRES DES MESSES SAMEDI DIMANCHE 18h30 9h30 10h30 11h JUILLET 6 juillet Rethonvillers 7 juillet Moyencourt Athies Ham 13 juillet Estrees-Mons 14 juillet Nesle 10h Ham 20 juillet Curchy 00450 - Ham Athies Ham 21 juillet 15h Villers-Saint-Christophe, messe et bénédiction des chauffeurs 27 juillet Matigny 28 juillet page 2 Nesle Ham PAGE TABLEAUAOÛT DES MESSES 3 août Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise 4 août Athies Ham 10 août Saint-Christ-Briost 11 août Nesle 14 août Athies Assomption 15 août Nesle Ham Assomption 17h procession et messe à Buverchy (grotte) 17 août Bethencourt 18 août Athies Ham 24 août Croix-Moligneaux Ham, messe en plein air 25 août Nesle aux Hardines 31 août Rethonvillers SEPTEMBRE Ham : Au Revoir 1er septembre Athies à l’abbé Albert Saelens 7 septembre Estrees-Mons 8 septembre Moyencourt Nesle Ham 14 septembre Voyennes Ham : Accueil 15 septembre Athies de l’abbé Léon Lee 21 septembre Matigny 22 septembre Douilly Nesle Ham 28 septembre Nesle - Ham Ham 29 septembre Saint-Firmin Gérant : Alain DESSAINT VSL TRANSPORT VOYAGEURS AÉROPORTS TOUTES DISTANCES Une référence La différence Rue du Dr. Camille Gautier 80190 NESLE 03 22 88 23 39 2 SOMMAIRE EDITORIAL Monseigneur Leborgne nommé vice-président 4 Vivement les vacances Les Scouts en balade… 5 C’est le cri des enfants et des jeunes au cours de Fraternelle rencontre pour l’année scolaire. -

Muille Et Une Nouvelles N°28

N°28 Décembre 2010 Bulletin édité par la mairie et http://mairiemuillehttp://mairiemuille----villette.evillette.evillette.e----monsite.commonsite.com l'équipe communication de Muille-Villette mail : [email protected] QUE S’EST-IL PASSÉ EN 2010 ? La fin d’année se termine avec notre rue principale parée de mille feux. Travaux de voirie Sous ses fastes, les membres du Conseil La troisième tranche de travaux de rénovation de trottoirs est en cours de réalisa- Municipal, la Directrice de l’école, ses tion côté pair de la rue de Paris du numéro 80 au numéro 116. Collègues, les Présidents d’associations et leurs membres, l’ensemble du per- sonnel et l’équipe communication se Sécurité routière joignent à moi pour vous souhaiter de bonnes fêtes de fin d’année. Votre sécurité n’a pas été oubliée : Que 2011 soit une année riche à parta- ger en famille et entre amis. Plusieurs marquages au sol, passages protégés, sont ou seront réalisés sur toutes les voiries jouxtant la rue de Paris. Je vous signale que les traditionnels vœux du Maire auront lieu le 07 janvier 2011 à 19 h 00 auxquels vous Deux places de stationnement ont été supprimées à l’angle de la rue de Paris et de êtes tous conviés. la rue Albert Letuppe (dans le sens Golancourt/Muille-Villette) afin de favoriser la visibilité des véhicules sortant de la rue Albert Letuppe. N’oubliez pas de nous retourner le cou- pon réponse pour celles ou ceux Ces places supprimées seront matérialisées par la mise en place de «zébra ». -

Tome 4 Appreciation Du Projet Eolien Douilly Et Matigny Avis Et Conclusion Du Commissaire Enquêteur

Départements de la Somme Projet éolien Communes de Douilly et Matigny (80400) Dans le cadre de la Demande d’autorisation unique en vue d’exploiter un parc éolien comprenant, 13 aérogénérateurs et 4 postes de livraison sur le territoire des communes de Douilly et Matigny par le SAS parc éolien Nordex LIX. du 13 juin 2016 au 13 juillet 2016 TOME 4 APPRECIATION DU PROJET EOLIEN DOUILLY ET MATIGNY AVIS ET CONCLUSION DU COMMISSAIRE ENQUÊTEUR Amiens 4 aout 2016 DEMANDE D’AUTORISATION UNIQUE GUY MARTINS, TITULAIRE JEAN-MARIE ALLONNEAU, SUPPLEANT SOMMAIRE DU TOME 3 1 LE PROJET ET SON COUT ........................................................................................................... 3 2 LA SOCIETE PORTANT LE PROJET .......................................................................................... 3 2.1 La Société Nordex : Un groupe international ................................................................ 3 2.2 Le filiale Française ......................................................................................................... 4 3 LE DEROULEMENT DE L’ENQUETE ET LE CLIMAT .......................................................... 5 3.1 Le déroulement de l’enquête .......................................................................................... 5 3.2 Le climat de l’enquête .................................................................................................... 6 4 ANALYSE DES OBSERVATIONS ET DECLINAISON DES THEMES .................................. 6 4.1 Méthodologie ................................................................................................................ -

CR Du 29 Juillet 2020

COMMUNAUTE DE COMMUNES DE L’EST DE LA SOMME COMPTE RENDU SEANCE DU 29 JUILLET 2020 L’an deux mille vingt, le vingt neuf juillet, à 8 heures 30, le Conseil Communautaire de l’Est de la Somme, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au pôle multifonction de NESLE. INSTALLATION D’UN CONSEILLER COMMUNAUTAIRE Monsieur le Président informe l’Assemblée de la démission du Conseil Communautaire de l’Est de la Somme de Monsieur Paul PILOT, conseiller communautaire de la commune de NESLE, par lettre en date du 16 juillet 2020, Il convient d’installer Monsieur PECRIAUX Lucas, conseiller communautaire, en remplacement de Monsieur PILOT Paul, démissionnaire, pour siéger au sein du Conseil de la Communauté de Communes de l’Est de la Somme, Le Conseil Communautaire déclare installé dans les fonctions de conseiller communautaire, Monsieur PECRIAUX Lucas. ------------ L’an deux mille vingt, le vingt neuf juillet, à 8 heures 30, le Conseil Communautaire de l’Est de la Somme, légalement convoqué, s’est réuni au pôle multifonction de NESLE, sous la présidence de Monsieur José RIOJA, Président. Etaient présents tous les membres en exercice, à l’exception de MM. DE WITASSE THEZY Charles, BLONDELLE Pascal, Mme VASSEUR Julie, M. DUCAMPS Thomas, Mme POLIN Justine, MM. POTIER Bruno, FORMAN Nicolas, LAOUT Didier, MEREL Michel, MUSEUX Gérard, LEMAITRE Jean-Pierre. M. DE WITASSE THEZY Charles avait donné pouvoir à M. WISSOCQ Jean-Marc. M. BLONDELLE Pascal avait donné pouvoir à M. DOUTART Jean-Luc. Mme VASSEUR Julie avait donné pouvoir à Mme CHAPUIS-ROUX Elodie. M. DUCAMPS Thomas avait donné pouvoir à Mme VERGULDEZOONE Nathalie. -

753 Roye/Nesle – Hombleux – Ham Horaires Valables Du 6 Juin Au 3 Juil

753 ROYE/NESLE – HOMBLEUX – HAM HORAIRES VALABLES DU 6 JUIN AU 3 JUIL. 2020 PERIODE SCOLAIRE Jours de circulation LMmJV LMmJV mS 53131 53132 53100 ROYE Rue de Goyencourt 06:20 ROYE Ancienne station service 06:24 CARREPUIS La Place 06:28 BALATRE Centre 06:32 MARCHE ALLOUARDE Centre 06:35 RETHONVILLERS Village Eglise 06:36 BILLANCOURT Centre 06:39 CRESSY OMENCOURT Abri RD 06:43 ERCHEU Ecole maternelle 06:48 CURCHY Rue de Manicourt 06:15 I MESNIL SAINT NICAISE Le Petit - Calvaire 06:23 I MESNIL SAINT NICAISE Mairie Ecole 06:27 I NESLE Mairie 06:35 I NESLE Collège 06:40 I LANGUEVOISIN QUIQUERY Place publique 06:45 I MOYENCOURT Jeu d'Arc 06:49 I BUVERCHY Intersection rte de Bacquencourt 06:53 I BACQUENCOURT (HOMBLEUX) Chaussée de Buverchy 06:55 I CANISY (HOMBLEUX) Salle Jourdel I I 10:05 HOMBLEUX La Raperie 06:58 I I HOMBLEUX Mairie-Ecole 07:00 I 10:09 VOYENNES Rue du Haut 07:05 I I BUNY (VOYENNES) Espace des Templiers 07:07 I I VOYENNES Salle des fêtes 07:10 I I OFFOY Eglise 07:14 I I CANISY (HOMBLEUX) Salle Jourdel 07:18 I I EPPEVILLE Mairie (rue du Maréchal Leclerc) 07:25 I I ESMERY HALLON Haut de Hallon I 06:53 I ESMERY HALLON Mairie I 06:54 10:15 VERLAINES (EPPEVILLE) Place I 06:58 I MUILLE VILLETTE Villette I 07:03 I MUILLE VILLETTE Mairie I 07:05 I GOLANCOURT Ecole I 07:10 I FLAVY LE MELDEUX Centre I 07:15 I LE PLESSIS PATTE D'OIE Centre I 07:17 I BERLANCOURT Route de Villeselve I 07:19 I VILLESELVE Route de Brouchy RD I 07:22 I BROUCHY Mairie I 07:25 I AUBIGNY (BROUCHY) Marais et Poiteux I 07:26 I BROUCHY Marais et Chauny (Rte de Ham RD) I 07:27 I MUILLE VILLETTE Hypermarché I I 10:20 HAM République 07:31 07:30 10:25 HAM Lycée Professionnel 07:35 07:35 Jours de circulation : L " Lundi ; M " Mardi ; m " Mercredi ; J " Jeudi ; V " Vendredi ; S " Samedi Attention : Les cars ne circulent pas les jours fériés (lundi de Pentecôte compris). -

BROUCHY Samedi 3 Juin 2017

BROUCHY samedi 3 juin 2017 "ché 10km ed'Brouchy" clt n° lic nom prénom club ville an cat cat rg km h:mn:s kmh 10 km 1 464 U MARCEL SEBASTIEN CHERIZIENNE 1976 V1 H 1 10 00:37:00 16,216 2 463 C D'HAENE CLEMENT MATIGNY 1988 SE H 1 10 00:37:20 16,071 3 443 U SOJA JOHNNY CAP21 1980 SE H 2 10 00:38:10 15,721 4 445 U VALINGOT RICHARD CAP21 1976 V1 H 2 10 00:39:14 15,293 5 447 C LEFEVRE CEDRIC MOYENCOURT 1976 V1 H 3 10 00:40:20 14,876 6 436 C BERTAUX CHRISTOPHE ARTEMPS 1973 V1 H 4 10 00:40:48 14,706 7 442 C DECHAUNE JEROME COGNAC 1978 SE H 3 10 00:40:56 14,658 8 438 C ALLARD ERIC HAM 1986 SE H 4 10 00:41:03 14,616 9 462 C GAGA ALEXANDRE BOVES 1981 SE H 5 10 00:42:20 14,173 10 451 F LOFFROY GERARD COMPIEGNE ASPTT 1954 V3 H 1 10 00:42:34 14,096 11 474 U DROUVROY MICKAEL CAP21 1981 SE H 6 10 00:42:35 14,090 12 433 U VERON DIDIER 24HNS EPPEVILLE 1956 V3 H 2 10 00:42:51 14,002 13 473 F TRANNIN KATALIN VILLERS-COTTERÊTS 1972 V1 F 1 10 00:43:17 13,862 14 455 C PERSONNE CATHERINE BROUCHY 1974 V1 F 2 10 00:43:28 13,804 15 471 C BLERIOT OLIVIER MESNIL-BRUNTEL 1986 SE H 7 10 00:43:29 13,798 16 432 C BOCQUET BRUNO GRICOURT 1964 V2 H 1 10 00:44:39 13,438 17 465 C CARTIGNY LAURENT LESDINS 1969 V1 H 5 10 00:46:02 13,034 18 461 C D'HAENE GERALDINE BOVES 1983 SE F 1 10 00:46:27 12,917 19 453 F TETART JEAN CLAUDE CAP21 1956 V3 H 3 10 00:46:50 12,811 20 450 C BONARD OLIVIER BROUCHY 1977 V1 H 6 10 00:47:24 12,658 21 452 C CAPELLE FREDERIC ANGUILCOURT 1979 SE H 8 10 00:47:41 12,583 22 444 C JANEAU AURELIE MUILLE-VILLETTE 1982 SE F 2 10 00:47:47 12,557 23 476 C BURKOWSKI -

La Nouvelle Année Est Arrivée, Et En Dépit D'un

EDITO La nouvelle année est arrivée, et en dépit d’un environnement économique perturbé, qui incite à la prudence, la commission communication a maintenu en 2009 tous les caps qu’elle s’était fixée, dont celui de « relooker » votre bulletin avec une couverture plus moderne et des textes et des photos plus lisibles dans le respect de la tradition de l’imprimerie en abandonnant le concept d’assemblage des photocopies. Le tout rendu possible par les progrès de l’informatique et de la numérisation, avec de surcroît une diminution des coûts. Ce bulletin municipal succède au n° 85 et s’inscrit en droite ligne, dans la continuité de l’évolution inéluctable. Sans rupture avec le passé, consacré essentiellement à la vie de nos associations, qui demeurent la plus grande dimension « du mieux vivre ensemble » de Notre Village, grâce à la convivialité de leurs différentes initiatives animés par des bénévoles. Enfin, pour conclure ce propos, la commission communication, vous rappelle que sa mission d’information est souvent délicate : Elle se doit de s’inscrire dans la durée, ce que nous assumons, mais aussi d’adapter ses messages à toutes vos préoccupations et de s’adresser à tous les publics : Donc, n’oubliez pas de nous aider en nous faisant part de vos commentaires : Bons ou mauvais, ils nous permettront d’évoluer! En espérant qu’il vous plaira, bonne lecture à tous ! Ce bulletin, tiré à 320 exemplaires, est sorti des presses de FOLIO 7 à Péronne, son pendant est également diffusé sur le Web : www.monchylagache.fr Rappel aux Associations des conditions de remise des documents à publier Envoi de l’information de préférence par courriel à [email protected], mais tous les autres supports : clef USB, Disquette, CD et aussi le texte sur papier sont acceptés, mais pour ce dernier cas, la date limite de remise des documents est avancée (Informations à prendre auprès du secrétariat de mairie). -

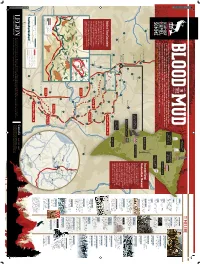

Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, Onwas Them, Trained a Few and Most Were Minutes Within Killed of the Assault

2015-12-18 2:03 PM Hunter’s CWGC TIMELINE Cemetery 1500s June 1916 English fishermen establish The regiment trains seasonal camps in Newfoundland in the rain and mud, waiting for the start of the Battle of the Somme 1610 The Newfoundland Company June 28, 1916 Hawthorn 51st (Highland) starts a proprietary colony at Cuper’s Cove near St. John’s The regiment is ordered A century ago, the Newfoundland Regiment suffered staggering losses at Beaumont-Hamel in France Ridge No. 2 Division under a mercantile charter to move to a forward CWGC Cemetery Monument granted by Queen Elizabeth I trench position, but later at the start of the Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. At the moment of their attack, the Newfoundlanders that day the order is postponed July 23-Aug. 7, 1916 were silhouetted on the horizon and the Germans could see them coming. Every German gun in the area 1795 Battle of Pozières Ridge was trained on them, and most were killed within a few minutes of the assault. German front line Newfoundland’s first military regiment is founded 9:15 p.m., June 30 September 1916 For more on the Newfoundland Regiment, Beaumont-Hamel and the Battle of the Somme, to 2 a.m., July 1, 1916 Canadian troops, moved from go to www.legionmagazine.com/BloodInTheMud. 1854 positions near Ypres, begin Newfoundland becomes a crown The regiment marches 12 kilo- arriving at the Somme battlefield Y Ravine CWGC colony of the British Empire metres to its designated trench, Cemetery dubbed St. John’s Road Sept. -

À Amiens Pour La Saint-Firmin

LA VIE ET LES CHRÉTIENS EN HAUTE-SOMME ATHIES HAM NESLE SEPTEMBRE 2019 SEPTEMBRE E N° 30 TRIMESTRIEL - 1,25 - TRIMESTRIEL TOUS À AMIENS POUR LA SAINT-FIRMIN PROCHAIN NUMÉRO DÉCEMBRE 2019 SECTEUR / P5 NESLES / P8 ATHIES / P10 Rentrée des scouts Profession de foi Souvenir de pélerinage 450 HORAIRES DES MESSES SAMEDI DIMANCHE 18h30 9h30 10h30 11h SEPTEMBRE Dimanche 1er Ham Samedi 7 Estrees-Mons Dimanche 8 Nesle Ham Samedi 14 Voyennes Dimanche 15 Athies Ham accueil de l’abbé Léon Lee Samedi 21 Matigny 00450 - Ham Dimanche 22 Douilly Nesle Ham Samedi 28 Nesle Ham Dimanche 29 Saint-Firmin Amiens OCTOBRE Samedi 5 Mesnil-Saint-Nicaise page 2 Dimanche 6 Athies Ham (confirmation) Samedi 12 Saint-Christ-Briost PAGE TABLEAU DES MESSES Dimanche 13 Hombleux Nesle Ham Samedi 19 Nesle Dimanche 20 Sancourt Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 26 Monchy-Lagache Dimanche 27 Esmery Hallon Nesle Ham NOVEMBRE Vendredi 1er Ercheu Nesle Ham Samedi 2 Croix-Moligneaux Dimanche 3 Villers-Saint-Christophe Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 9 Monchy-Lagache Dimanche 10 Offoy Nesle Ham Samedi 16 Nesle Dimanche 17 Brouchy Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 23 Monchy-Lagache Dimanche 24 Aubigny aux Kaisnes Nesle Ham Samedi 30 Nesle DÉCEMBRE Dimanche 1er Moyencourt Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 7 Monchy-Lagache Dimanche 8 Douilly Nesle Ham Samedi 14 Nesle Dimanche 15 Hombleux Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 21 Monchy-Lagache Dimanche 22 Sancourt Nesle Ham Mardi 24 Nesle -Eppeville Mercredi 25 Monchy-Lagache Ham Samedi 28 Monchy-lagache Dimanche 29 Ercheu Nesle - 16h30 Ham Gérant : Alain DESSAINT VSL TRANSPORT VOYAGEURS AÉROPORTS TOUTES DISTANCES Une référence La différence Rue du Dr. -

Sectorisation Par Commune

Conseil départemental de la Somme / Direction des Collèges Périmètre de recrutement des collèges par commune octobre 2019 Code communes du secteur Libellé du secteur collège commune 80001 Abbeville voir sectorisation spécifique 80002 Ablaincourt-Pressoir CHAULNES 80003 Acheux-en-Amiénois ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80004 Acheux-en-Vimeu FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80005 Agenville BERNAVILLE 80006 Agenvillers NOUVION AGNIERES (ratt. à HESCAMPS) POIX 80008 Aigneville FEUQUIERES EN VIMEU 80009 Ailly-le-Haut-Clocher AILLY LE HAUT CLOCHER 80010 Ailly-sur-Noye AILLY SUR NOYE 80011 Ailly-sur-Somme AILLY SUR SOMME 80013 Airaines AIRAINES 80014 Aizecourt-le-Bas ROISEL 80015 Aizecourt-le-Haut PERONNE 80016 Albert voir sectorisation spécifique 80017 Allaines PERONNE 80018 Allenay FRIVILLE ESCARBOTIN 80019 Allery AIRAINES 80020 Allonville RIVERY 80021 Amiens voir sectorisation spécifique 80022 Andainville OISEMONT 80023 Andechy ROYE ANSENNES ( ratt. à BOUTTENCOURT) BLANGY SUR BRESLE (76) 80024 Argoeuves AMIENS Edouard Lucas 80025 Argoules CRECY EN PONTHIEU 80026 Arguel BEAUCAMPS LE VIEUX 80027 Armancourt ROYE 80028 Arquèves ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80029 Arrest ST VALERY SUR SOMME 80030 Arry RUE 80031 Arvillers MOREUIL 80032 Assainvillers MONTDIDIER 80033 Assevillers CHAULNES 80034 Athies HAM 80035 Aubercourt MOREUIL 80036 Aubigny CORBIE 80037 Aubvillers AILLY SUR NOYE 80038 Auchonvillers ALBERT PM Curie 80039 Ault MERS LES BAINS 80040 Aumâtre OISEMONT 80041 Aumont AIRAINES 80042 Autheux BERNAVILLE 80043 Authie ACHEUX EN AMIENOIS 80044 Authieule DOULLENS 80045 Authuille -

753 Roye/Nesle – Hombleux – Ham Horaires Valables Du 2 Sept

753 ROYE/NESLE – HOMBLEUX – HAM HORAIRES VALABLES DU 2 SEPT. 2021 AU 6 JUIL. 2022 PETITES PERIODE SCOLAIRE VACANCES Jours de circulation LMmJV LMmJV mS mS 53131 53132 53100 53100 ROYE Rue de Goyencourt 06:15 ROYE Ancienne station service 06:19 CARREPUIS La Place 06:23 BALATRE Centre 06:27 MARCHE ALLOUARDE Centre 06:30 RETHONVILLERS Village Eglise 06:32 BILLANCOURT Centre 06:36 CRESSY OMENCOURT Abri RD 06:40 ERCHEU Ecole maternelle 06:44 CURCHY Rue de Manicourt 06:15 I MESNIL SAINT NICAISE Le Petit - Calvaire 06:23 I MESNIL SAINT NICAISE Mairie Ecole 06:27 I NESLE Mairie 06:35 I NESLE Collège 06:40 I LANGUEVOISIN QUIQUERY Place publique 06:45 I MOYENCOURT Jeu d'Arc 06:49 I BUVERCHY Intersection rte de Bacquencourt 06:53 I BACQUENCOURT (HOMBLEUX) Chaussée de Buverchy 06:55 I CANISY (HOMBLEUX) Salle Jourdel I I 10:05 10:05 HOMBLEUX La Raperie 06:58 I I I HOMBLEUX Mairie-Ecole 07:00 I 10:09 10:09 HOMBLEUX Hansart 07:01 I I I VOYENNES Rue du Haut 07:05 I I I BUNY (VOYENNES) Espace des Templiers 07:07 I I I VOYENNES Salle des fêtes 07:10 I I I OFFOY Eglise 07:14 I I I CANISY (HOMBLEUX) Salle Jourdel 07:18 I I I EPPEVILLE Mairie (rue du Maréchal Leclerc) 07:25 I I I ESMERY HALLON Haut de Hallon I 06:49 I I ESMERY HALLON Mairie I 06:50 10:15 10:15 MUILLE VILLETTE Villette I 06:56 I I VERLAINES (EPPEVILLE) Place I 06:58 I I MUILLE VILLETTE Mairie I 07:00 I I GOLANCOURT Ecole I 07:05 I I FLAVY LE MELDEUX Centre I 07:10 I I LE PLESSIS PATTE D'OIE Centre I 07:13 I I BERLANCOURT Route de Villeselve I 07:15 I I VILLESELVE Route de Brouchy RD I 07:18 I I BROUCHY Mairie I 07:24 I I AUBIGNY (BROUCHY) Marais et Poiteux I 07:26 I I BROUCHY Marais et Chauny (Rte de Ham RD) I 07:27 I I MUILLE VILLETTE Hypermarché I I 10:20 10:20 HAM République 07:31 07:30 10:25 10:25 HAM Lycée Professionnel 07:35 07:35 Jours de circulation : L " Lundi ; M " Mardi ; m " Mercredi ; J " Jeudi ; V " Vendredi ; S " Samedi Attention : Les cars ne circulent pas les jours fériés (lundi de Pentecôte compris).