30Th ANNIVERSARY ESSAYS Member, Wye Academic Programs Advisory Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIVING OPENLY SECULAR in BLACK COMMUNITIES a Resource for African-Americans Living Openly Secular in Black Communities: a Resource for African-Americans

LIVING OPENLY SECULAR IN BLACK COMMUNITIES A Resource for African-Americans Living Openly Secular in Black Communities: A Resource for African-Americans. Copyright © 2015 Openly Secular. Some Rights Reserved. Content written by Jodee Hassad and Lori L. Fazzino, M.A., University of Nevada, Las Vegas Graphic design by Sarah Hamilton, www.smfhamilton.com This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International. More information is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Openly Secular grants permission for all non-commercial uses, including reproduction, distribution, and adaptation, with proper credit to Openly Secular and provides others with the same rights. 4 ABOUT THE Openly SECULAR Campaign Openly Secular is a coalition project that promotes tolerance and equality of people regardless of their belief systems. Founded in 2013, the Openly Secular Coalition is led by four organizations - Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science, Secular Coalition for America, Secular Student Alliance, and Stiefel Freethought Foundation. This campaign is also joined by national partner organizations from the secular movement as well as organizations that are allies to our cause. OUR MISSION The mission of Openly Secular is to eliminate discrimination and increase acceptance by getting secular people - including atheists, freethinkers, agnostics, humanists and nonreligious people - to be open about their beliefs. SPECIAL THanks We would like to thank secular activist Bridget Gaudette, and Mandisa Thomas from Black Nonbelievers, Inc., www.blacknonbelievers.org, for providing direction and feedback on this project. USING THIS TOOLKIT In this toolkit you’ll find key ideas, quotes from openly secular individuals, and links to the Openly Secular website that will provide you with more information about various topics. -

Chapter 15: Resources This Is by No Means an Exhaustive List. It's Just

Chapter 15: Resources This is by no means an exhaustive list. It's just meant to get you started. ORGANIZATIONS African Americans for Humanism Supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives. <a href="http://aahumanism.net">aahumanism.net</a> American Atheists The premier organization laboring for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion. <a href="http://atheists.org">atheists.org</a> American Humanist Association Advocating progressive values and equality for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers. <a href="http://americanhumanist.org">americanhumanist.org</a> Americans United for Separation of Church and State A nonpartisan organization dedicated to preserving church-state separation to ensure religious freedom for all Americans. <a href="http://au.org">au.org</a> Atheist Alliance International A global federation of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. <a href="http://atheistalliance.org">atheistalliance.org</a> Atheist Alliance of America The umbrella organization of atheist groups and individuals around the world committed to promoting and defending reason and the atheist worldview. <a href="http://atheistallianceamerica.org">atheistallianceamerica.org< /a> Atheist Ireland Building a rational, ethical and secular society free from superstition and supernaturalism. <a href="http://atheist.ie">atheist.ie</a> Black Atheists of America Dedicated to bridging the gap between atheism and the black community. <a href="http://blackatheistsofamerica.org">blackatheistsofamerica.org </a> The Brights' Net A bright is a person who has a naturalistic worldview. -

The Muslim Woman Activist’: Solidarity Across Difference in the Movement Against the ‘War on Terror’

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘The Muslim woman activist’: solidarity across difference in the movement against the ‘War on Terror’ AUTHORS Massoumi, N JOURNAL Ethnicities DEPOSITED IN ORE 13 March 2019 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/36451 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication ‘The Muslim woman activist’: solidarity across difference in the movement against the ‘War on Terror’ Abstract Feminist scholars have widely noted the centrality of gendered discourses to the ‘War on Terror’. This article shows how gendered narratives also shaped the collective identities of those opposing the ‘War on Terror’. Using interview data and analysis of newspaper editorials from movement leaders alongside focus groups with grassroots Muslim women activists, this article demonstrates how, in responding to the cynical use of women’s rights to justify war, participants in the anti- ‘War on Terror’ movement offered an alternative story. Movement activists deployed representations of Muslim women’s agency to challenge the trope of the ‘oppressed Muslim woman’. I argue that these representations went beyond strategic counter-narratives and offered an emotional basis for solidarity. Yet, respondents in the focus groups illustrated the challenges of seeking agency through an ascribed identity; in that they simultaneously refused and relied upon dominant terms of the debate about Muslim women. Keywords Muslim women, social movements, war on terror, collective identity, symbol Introduction Something horrible flits across the background in scenes from Afghanistan, scuttling out of sight. -

Romantic Liberalism

Romantic Liberalism The role of individuality and autonomy in the opposition to Muslim veils among self-professed ‘enlightenment liberals’ By Gina Gustavsson Post-doc at the Department of Government, Uppsala University Visiting scholar at Nuffield College, University of Oxford [email protected] To be presented at the PSA annual conference, Cardiff, March 2013 NB: Work in progress, please do not cite or circulate without author’s permission Abstract This paper questions the theoretical coherence and empirical fruitfulness of ‘enlightenment liberalism’. In recent years, this concept has established itself outside of political theory and in the empirical literature on immigration, ethnicity and citizenship. This literature tends to single out enlightenment liberalism as the main culprit behind recent instances of intolerance in the name of liberty. The paradigmatic case of this is taken to be the legal prohibitions against the Muslim veil that have recently been adopted by several European countries. The present paper, however, tries to show that the focus on enlightenment liberalism has in fact led to an unsatisfactory account of the opposition to the Muslim veil in previous research. In what follows, I first examine the theoretical roots of ‘enlightenment liberalism’, which results in the conclusion that the concept contains two very different strands: one rooted in the ideal of Kantian autonomy and another rooted in Millian and Emersonian individuality. This latter strand, I suggest, should be called ‘romantic liberalism’. It is this strand, I then show in the empirical analysis, that seems to have inspired some of the most vehement critics of the Muslim veil. Although they have been pitched as typical ‘enlightenment liberals’, I argue that they are in fact ‘romantic liberals’. -

Social Consciousness, Metaphysical Contents and Aesthetics in Select Anglophone African Factions

SOCIAL CONSCIOUSNESS, METAPHYSICAL CONTENTS AND AESTHETICS IN SELECT ANGLOPHONE AFRICAN FACTIONS By Abidemi Olufemi ADEBAYO (Matric No.104957) A Thesis in the Department of English, Submitted to the Faculty of Arts in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN SEPTEMBER, 2014 CERTIFICATION I certify that this research was carried out by Abidemi Olufemi ADEBAYO in the Department of English, University of Ibadan, under my supervision. Professor Nelson O. Fashina Date Department of English University of Ibadan ii DEDICATION To all men of goodwill in Africa. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge God for the gift of life. I thank my supervisor, Professor Nelson Fashina, for the sound tutelage I received from him all through the different stages of my academic career in the Department of English, University of Ibadan. He sowed the seed of thorough academic scholarship in me in my undergraduate days, nurtured it during my Master‘s degree programme and fortified same in the supervision of this research. I thank the professor profoundly. The impact of his mentoring on me is indelible. I also thank all the lecturers in the Department for constant encouragement and advice. Specific mention is made of Professor Lekan Oyeleye, Professor Remi Raji-Oyelade, Professor Tunde Omobowale, Professor Ayo Kehinde, Professor Obododinma Oha, Dr. Remy Oriaku, Dr. M. T. Lamidi, Dr. Toyin Jegede, Dr. Nike Akinjobi, Dr. Ayo Osisanwo, Dr. Ayo Ogunsiji and Dr. Adesina Sunday. I benefited from their wealth of knowledge. They guided me in the course of writing my thesis. It is important to me to appreciate the suggestion that Yinka Akintola made on how to procure books for the research. -

The New Atheism: Ten Arguments That Dont Hold Water Free

FREE THE NEW ATHEISM: TEN ARGUMENTS THAT DONT HOLD WATER PDF Michael Poole | 96 pages | 01 May 2010 | Lion Hudson Plc | 9780745953939 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom ARIZONA ATHEIST: The 'New' Atheism: 10 Arguments That Don't Hold Water?: A Refutation Chris Bell. Two contemporary atheists who do not believe God exists - Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens - also seem to be overly angry persons. Dawkins reckons that 'good scientists who are sincerely religious Michael Poole, Visiting Research Fellow in Science and Religion at King's College, London, has written a small book of ten chapters - 96 pages - which could and should! His main question: do the ideas of the The New Atheism: Ten Arguments That Dont Hold Water and noisy 'new atheists' hold water? He devotes a little chapter to each of the ten most common arguments for not believing in the existence of God, and in summary, says: Science and religion are addressing different questions. For example, science cannot help us with 'Why is there something rather than nothing? Although Dawkins asserts in one place 'Atheists do not have faith' This illustrates what he calls 'the fallacy of the excluded middle' a recurring phrase in the book - choosing between only two positions when others are logically possible. Most of the favorite theoretical constructs are here: Planck's constant, the god meme, functionalism, instrumentalism, direct vs. The target-audience is obviously undergraduates. The flavour is quite British: Chapter 10 is titled 'Unpeeling the Cosmic Onion' a fascinating discussion of 'universe' and 'multiverse'there's mention of 'grown-up talk' etc. I believe that a serious flaw in Poole's apologetic is the absence of a Christological basis for belief in the existence of God: the approach is mostly scientific and philosophical. -

The Political Economy of Marriage: Joanne Payton

‘Honour’ and the political economy of marriage Joanne Payton Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD, 2015 i DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date: 13 April 2015 Summary ‘Honour’-based violence (HBV) is defined as a form of crime, predominantly against women, committed by the agnates of the victim, often in collaboration, which are justified by the victims’ perceived violation of social norms, particularly those around sexuality and gender roles. While HBV is often considered as a cultural phenomenon, I argue that the cross-cultural distribution of crimes fitting this definition prohibits a purely cultural explanation. I advance an alternate explanation for HBV through a deployment of the cultural materialist strategy and the anthropological theories of Pierre Bourdieu, Claude Lévi-Strauss (as interpreted by Gayle Rubin) and Eric Wolf. -

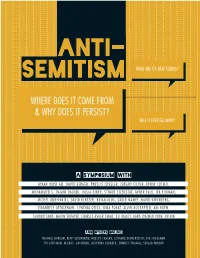

Where Does It Come from & Why Does It Persist?

ANTI- SEMITISM WHAT ARE ITS NEW FORMS? WHERE DOES IT COME FROM & WHY DOES IT PERSIST? WILL IT EVER GO AWAY? A SYMPOSIUM WITH AYAAN HIRSI ALI, DAVID BERGER, PHYLLIS CHESLER, JEREMY COHEN, IRWIN COTLER, MOHAMMED S. DAJANI DAOUDI, HASIA DINER, STUART EIZENSTAT, AVNER FALK, IRA FORMAN, MICHEL GURFINKIEL, DAVID KERTZER, BRIAN KLUG, DAVID MAMET, DAVID NIRENBERG, EMANUELE OTTOLENGHI, CYNTHIA OZICK, DINA PORAT, ALVIN ROSENFELD, ARI ROTH, SHLOMO SAND, MAXIM SHRAYER, CHARLES ASHER SMALL, ELI VALLEY, HANS-JOACHIM VOTH, XU XIN AND OTHERS ONLINE: MICHAEL BARKUN, BENT BLÜDNIKOW, ROBERT CHAZAN, LEONARD DINNERSTEIN, EVA FOGELMAN ZVI GITELMAN, MICHAEL GOLDFARB, JONATHAN JUDAKEN, SHMUEL TRIGANO, SERGIO WIDDER ART CREDIT 34 JULY/AUGUST 2013 INTERVIEWS BY: SARAH BREGER, DINA GOLD,GEORGE JOHNSON, CAITLIN YOSHIKO KANDIL, SALA LEVIN & JOSH TAPPER THE OLDEST HATRED IS BY SOME ACCOUNTS ALIVE AND WELL, BY OTHERS AN OVERUSED EPITHET. WE TALK WITH THINKERS FROM AROUND THE GLOBE FOR A CRITICAL AND SURPRISINGLY NUANCED EXAMINATION OF ANTI-SEMITISM'S ORIGINS AND STAYING POWER. DAVID BERGER Europe meant that Jews became the Christianity could not eliminate the evil OUTSIDERS & ENEMIES quintessential Other, and they conse- character of Jewish blood. quently became the primary focus of David Berger is editor of History and In the ancient Greco-Roman world, peo- hostility even in ways that transcended Hate: The Dimensions of Anti-Semi- ple evinced a wide variety of attitudes to- the theological. tism and Ruth and I. Lewis Gordon Pro- ward Jews. Some admired Jewish distinc- Once this focus on Jews as the Other fessor of Jewish History and dean of the tiveness, some were neutral, but others became entrenched, it continued into Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish were put off by the fact that unlike any modern Europe. -

The Conservative Embrace of Progressive Values Oudenampsen, Merijn

Tilburg University The conservative embrace of progressive values Oudenampsen, Merijn Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Oudenampsen, M. (2018). The conservative embrace of progressive values: On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics. [s.n.]. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. sep. 2021 The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics The conservative embrace of progressive values On the intellectual origins of the swing to the right in Dutch politics PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. E.H.L. Aarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de aula van de Universiteit op vrijdag 12 januari 2018 om 10.00 uur door Merijn Oudenampsen geboren op 1 december 1979 te Amsterdam Promotor: Prof. -

Reformist Islam

Working Paper/Documentation Brochure series published by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. No. 155/2006 Andreas Jacobs Reformist Islam Protagonists, Methods, and Themes of Progressive Thinking in Contemporary Islam Berlin/Sankt Augustin, September 2006 Contact: Dr. Andreas Jacobs Political Consulting Phone: 0 30 / 2 69 96-35 12 E-Mail: [email protected] Address: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, 10907 Berlin; Germany Contents Abstract 3 1. Introduction 4 2. Terminology 5 3. Methods and Themes 10 3.1. Revelation and Textual Interpretation 10 3.2. Shari’a and Human Rights 13 3.3. Women and Equality 15 3.4. Secularity and Freedom of Religion 16 4. Charges against Reformist Islam 18 5. Expectations for Reformist Islam 21 6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations 23 Select Bibliography 25 The Author 27 Abstract The debate concerning the future of Islam is ubiquitous. Among the Muslim contribu- tions to these discussions, traditionalist and Islamist arguments and perspectives are largely predominant. In the internal religious discourse on Islam, progressive thinkers play hardly any role at all. This bias is unwarranted – for a good number of Muslim intellectuals oppose traditionalist and Islamist ideas, and project a new and modern concept of Islam. Their ideas about the interpretation of the Qur’an, the reform of the Shari’a, the equality of men and women, and freedom of religion are often complex and frequently touch on political and societal taboos. As a consequence, Reformist Islamic thought is frequently ignored and discredited, and sometimes even stigma- tised as heresy. The present working paper identifies the protagonists, methods, and themes of Re- formist Islam, and discusses its potential as well as its limits. -

Reading Ayaan Hirsi Ali in Birmingham

Reading Ayaan Hirsi Ali in Birmingham Gina Khan Personal Trauma and Public Voice I am not just a woman who was born in a Muslim family; I am also a British citizen who loves her country and stands behind our soldiers who lose their limbs and lives fighting Jihadists and Islamists. I grew up with friends and neighbours from all walks of lives, gays, atheist, Christians, Sikhs, Hindus and Buddhists. My mother never taught me to hate or despise anyone from a different religion or culture. So I admire Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born Muslim woman who fled an arranged marriage to live in Holland where she became famous as an MP, a writer, a fighter for Muslim women’s rights and an opponent of terrorism. In her remarkable books Infidel and The Caged Virgin she tells us important truths that many of us have maybe suppressed. There are men who have written disparagingly about Ayaan who clearly have no idea how much courage that took. Ayaan shows us that personal trauma can be the spur to speak out against patriarchal communities which lock us away and religious preachers who say we are inferior. Because of my Mum, my Islam was always different to the dry and rigid literalist Islam that indoctrinated Ayaan. But the ‘caged virgin syndrome’ she writes about resonated powerfully with me. I too was coerced into marrying a first cousin. The marriage was a mental prison, as I lived to a script others had written for me. I set myself free when I broke my silence, but freedom came at a price. -

National Press Club Newsmaker Luncheon with Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Author of "Infidel" and Research Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB NEWSMAKER LUNCHEON WITH AYAAN HIRSI ALI, AUTHOR OF "INFIDEL" AND RESEARCH FELLOW AT THE AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE TOPICS INCLUDE: ISLAM AND THE WEST MODERATOR: JERRY ZREMSKI, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, JUNE 18, 2007 (C) COPYRIGHT 2005, FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC., 1000 VERMONT AVE. NW; 5TH FLOOR; WASHINGTON, DC - 20005, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FEDERAL NEWS SERVICE, INC. IS A PRIVATE FIRM AND IS NOT AFFILIATED WITH THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. NO COPYRIGHT IS CLAIMED AS TO ANY PART OF THE ORIGINAL WORK PREPARED BY A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT OFFICER OR EMPLOYEE AS PART OF THAT PERSON'S OFFICIAL DUTIES. FOR INFORMATION ON SUBSCRIBING TO FNS, PLEASE CALL JACK GRAEME AT 202-347-1400. ------------------------- MR. ZREMSKI: Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Jerry Zremski, and I'm the Washington bureau chief for the Buffalo News and president of the National Press Club. I'd like to welcome our club members and their guests here today, as well as the audience that's watching us live on C-SPAN. We're looking forward to today's speech, and afterwards I will ask as many questions as time permits. Please hold your applause during the speech so that we have as much time for questions as possible.