Strategies in Acting for Operatic Performance: Empowering the Powerful

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Episode Guide Episodes 001–032

Life Episode Guide Episodes 001–032 Last episode aired Wednesday April 8, 2009 www.nbc.com c c 2009 www.tv.com c 2009 www.nbc.com The summaries and recaps of all the Life episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ^¨ This booklet was LATEXed on December 31, 2011 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.31 Contents Season 1 1 1 Merit Badge . .3 2 Tear Asunder . .7 3 Let Her Go . .9 4 What They Saw . 11 5 The Fallen Woman . 13 6 Powerless . 15 7 A Civil War . 17 8 Farthingale . 19 9 Serious Control Issues . 21 10 Dig a Hole . 23 11 Fill It Up . 25 Season 2 27 1 Find Your Happy Place . 29 2 Everything... All the Time . 31 3 The Business of Miracles . 35 4 Not For Nothing . 39 5 Crushed . 43 6 Did You Feel That? . 47 7 Jackpot . 51 8 Black Friday . 55 9 Badge Bunny . 59 10 Evil...and his brother Ziggy . 63 11 Canyon Flowers . 67 12 Trapdoor . 71 13 Re-Entry . 75 14 Mirror Ball . 79 15 I Heart Mom . 81 16 Hit Me Baby . 85 17 Shelf Life . 89 18 3Women ............................................ 93 19 5 Quarts . 97 20 Initiative 38 . 101 21 One ............................................... 105 Actor Appearances 109 Life Episode Guide II Season One Life Episode Guide Merit Badge Season 1 Episode Number: 1 Season Episode: 1 Originally aired: Wednesday September 26, 2007 on NBC Writer: Rand Ravich Director: David Semel Show Stars: Damian Lewis (Charlie Crews), Brooke Langton (Constance), Brent Sexton (Bobby Starks), Adam Arkin (Ted Early), Sarah Shahi (Dani Reese), Robin Weigert (Lt. -

Today's TV Programming Aces on Bridge Decodaquote® Celebrity

KITSAPSUN «Monday, October 3, 2016 «7A Today’s TV programming MOVIES NEW 10/3/16 11:00 11:30 NOON 12:30 1:00 1:30 2:00 2:30 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 [KBTC] Sesame Tiger Curious Curious Dino Super Cat in Mystery Hour Nature Wild Wild Ready Odd Masterpiece Mystery! Masterpiece Mystery! Death in Paradise World Dancesport NOVA [KOMO] KOMO 4News The Chew (TVPG) General Hospital Seattle Refined Harry (TVPG) KOMO 4News News ABC KOMO 4News Wheel J’pardy! Dancing With the Stars (TVPG) Conviction (10:01) News [KING] New Day NW KING 5News Days of our Lives Dr. Phil (TV14) Ellen DeGeneres KING 5News at 4KING 5News at 5 News News News Evening The Voice (TVPG) Timeless (TVPG) News [KONG] Best Pan Ever! J. Meyer Paid News New Day NW T.D. Jakes (TV14) The Dr. Oz Show Rachael Ray Extra The List Inside Holly Dr. Phil (TV14) KING 5News at 9 News Dr Oz [KIRO] Young &Restless KIRO News The Talk (TV14) Bold Minute Million. Million. Judge Judge News News News CBS Insider ET Theory Kevin Scorpion (TV14) News [KCTS] Dino Dino Super Thomas Sesame Cat in Curious Curious Lidia Cook APlace to Call News Busi PBS NewsHour Tommy Emmanuel Carpenters: Close to You 30 Days to aYounger Heart [KMYQ] Divorce Divorce Judge Judge Judge Mathis Cops Cops Celeb Celeb Pawn Pawn Mother Mother Two Two Last Last Mod Mod Q13 News at 9Theory Theory Friends [KSTW] Patern Patern Hot Hot Robert Irvine People’s Court People’s Court Fam Fam Seinfeld Seinfeld Fam Fam Mike Broke Supergirl (TV14) Supergirl (TV14) Broke Mike Family -

Senate Keeps Health

20--MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. Oci. 6., 1989 TOWN OF MANCHESTER LEGAL NOTICE CARS I CARS b e c a u s e y o u never FOR SALE know when someone will DEADLINES; For classified odvertlsments to Zoning Commission will hold a public hear- FOR SALE be searching for the Item be published Tuesday through Saturday, the Monday October 16, 1989 at 7:00 P.M. in ttie Hearing w u have for sale, it's BUICK 1979 Skvhawk - 2 deadline Is noon on the day before publica Center, 494 Main Street, Manchester, Connec better to run your want ad door hatch, good con- 1984 HONDA Civic Wagon tion. For advertisements to be published ticut to hear and consider the following petition: - 646-0767 or 649-4554, for several days ... cancel dltlon, standard. Monday, the deadline Is 2:30 p.m. on Frldoy. MANCHESTER - DAY CARE REGULATIONS Jack.__________ ing It os soon os you aet $700/best offer. 644- results. Application to amend the following Sections of the 6343. 1986 JEEP Wagoneer Ll- Manchester Zoning Regulations: Article I. Section 2.01; Article SUBARU 198'2-GL, red, 5 mlted - Excellent con II. Sections 2.01.08, 2.01.14 Now; 2.02.09; 2.02.16 New; Soc- dition, 43,000 miles, CARS jg i I CARS 3.01.07 New; 3.02.07 New; Sections 4.01 03- speed, air, sunroof. CARS 140K miles. $600/best automatic, air condl- FOR SALE CARS 4.01.08 New; 4.02.08 New; 4.02.09 New; Sections 5.01 04- tlonlng, am/fm FOR SALE L l j FOR SALE FOR SALE 5.01.12 New; 5.02.08 New; 5.02.09 New; Sections 6.01 04- offer. -

Layout 1 (Page 2)

Cover me, men Syke takes classic rock to Myrtle Creek’s Music in the Park JULY 13-19, 2012 CURRENTS The News-Review’s guide to arts, entertainment and television INSIDE: What’s Happening/3 Calendar/5 Movies/7 Book Review/11 TV/15 Page 2, The News-Review Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, July 12, 2012 5541-672-338341-672-3383 LARGEST FURNITURE & MATTRESS SHOWROOMS WITH PRODUCTS MADE IN THE USA! Roseburg, Oregon, Currents—Thursday, July 12, 2012 The News-Review, Page 3 what’s HAPPENING ROSEBURG returns to Half Shell for a fourth time. Hot 100 singer REAL AP-PEAL Bell first performed there as an opener for Etta James in plays The Zoo 2006. Rock musician Uncle Since then, he has been a Kracker will perform July 21 finalist on the NBC reality at The Zoo. show “The X-Factor.” Kracker, 38, is best known All shows are free and start for the songs “Smile,” “Drift at 7 p.m. Away” and “Follow Me.” The Information: 541-677-1708 latter reached number five on or www.halfshell.org. the Billboard Top 100 in 2001. Kracker has released five albums since 2000. ROSEBURG The performance begins at Mark Chesnutt 5:30 p.m. at 2455 N.E. Dia- mond Lake Blvd., Roseburg. plays at The Zoo Tickets are $25 plus a $1.87 Country music singer Mark processing fee. Tickets can be Chesnutt will perform at The purchased through Zoo on Friday. www.zooroseburg.com. Chesnutt, 48, has recorded Information: 541-672-4488. multiple U.S. Billboard Hot Country Songs, including eight ROSEBURG No. -

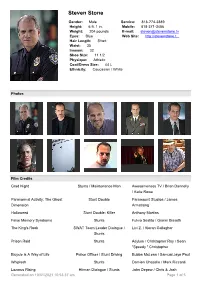

Steven Stone

Steven Stone Gender: Male Service: 818-774-3889 Height: 6 ft. 1 in. Mobile: 818-371-3456 Weight: 204 pounds E-mail: [email protected] Eyes: Blue Web Site: http://stevenstone.t... Hair Length: Short Waist: 35 Inseam: 32 Shoe Size: 11 1/2 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 44 L Ethnicity: Caucasian / White Photos Film Credits Grad Night Stunts / Maintenance Man Awesomeness TV / Brian Dannelly / Katie Rowe Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Stunt Double Paramount Studios / James Dimension Armstrong Halloweed Stunt Double: Killer Anthony Martins False Memory Syndrome Stunts Fulvio Sestito / Gianni Biasetti The King's Rook SWAT Team Leader Dialogue / Livi Z. / Kieran Gallagher Stunts Prison Raid Stunts Asylum / Christopher Ray / Sean "Speedy " Christopher Bicycle is A Way of Life Police Officer / Stunt Driving Bubba McLean / Samual Jaye Paul Whiplash Stunts Damien Chazelle / Mark Riccardi Lazarus Rising Hitman Dialogue / Stunts John Depew / Chris & Josh Generated on 10/01/2021 10:53:37 am Page 1 of 5 Bradley Extraction Smoking Guard / Stunts RFD / Tony Giglio / James Lew Capture Stunts / Scuba Water Safety Georgia Lee / La Faye Baker Skywings Stunt Coordinator Frederick Park The Devil's in the Details Asst. Stunt Coordinator Andy Dylan / Keith Campbell Sparks Stunts William Katt Prods. / Brady Romberg Paranormal Activity 3 Stunt Double (David Shorter) Paramount / Joost / Schulman / Rob King The Bunglers Stunts / Asst. Stunt Coordinator Glenn Camhi / Kai Nuuhiwa Karma Stunt Coordinator Ingrid Patzwahl Reign Stunt Coordinator Drew Fognani Daniel Don't Cry Stunt Coordinator Ignatius Lin Kill Katie Malone Stunt Utility Scott Leva Circle of Eight Stunt Utility John Moio Alvin & The Chipmunks II Stunts John Moio L.A. -

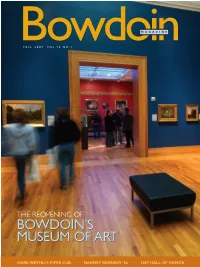

2007-Fall.Pdf

MAGAZINE BowdoinFALL 2007 VOL.79 NO.1 THE REOPENING OF BOWDOIN’S MUSEUM OF ART MARK WETHLI’S PIPER CUB • NANNEY KENNEDY ’82 • 2007 HALL OF HONOR BowdoinMAGAZINE FALL 2007 FEATURES 16 Pictures at an Exhibition: The Reopening of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art 16 BY SELBY FRAME PHOTOGRAPHS BY JAMES MARSHALL AND MICHELE STAPLETON The Museum of Art celebrated its public reopening and its renewed position as the cornerstone of arts and culture at Bowdoin in October, following an ambitious $20.8 million renovation and expansion project. Selby Frame gives us a look at the last stages CONTENTS of the project – the preparation of the exhibitions – as well as a glimpse of the first visitors. 24 Arrivals and Departures BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM 24 PHOTOGRAPHS BY JAMES MARSHALL Professor of Art Mark Wethli came to Bowdoin in 1985 to direct Bowdoin’s studio art program. In the 22 years since then,Wethli has mentored and inspired countless students and has led Bowdoin in elevating its profile in the state and national art scenes. In addition to discussing Wethli’s most recent project, Piper Cub, Ed Beem writes of the many forms Wethli’s aesthetic vision has taken over the years. 30 30 Craftswoman, Farmer, Entrepreneur BY JOAN TAPPER PHOTOGRAPHS BY GALE ZUCKER Nanney Kennedy ’82, a Bowdoin lacrosse player who earned her degree in the sociology of art, followed her own path from artisan to businesswoman and advocate for sustainability. Joan Tapper, who inter- viewed Kennedy for her upcoming book Shear Spirit: Ten Fiber Farms,Twenty Patterns and Miles of Yarn (Potter Craft:April 2008), tells us how she built new dreams on old foundations. -

Five Standout Secondary School Athletes

SPRING/SUMMER 2014 Five Standout Secondary School Athletes 2015 Audi A3 Review Chrissy Bendzinski See page 22 RHAM 8 CONTENTS WELCOME 2 A letter from the Hoffmans. SNAPSHOTS 4 Hoffman and the community. DETAILS 6 Gizmos and Gadgets. By Robert Bailin 12 COVER STORY 8 Five Standout Student Athletes Our reporter profiles five standout secondary school athletes from the Greater Hartford area, unearthing some of their accomplishments, their future plans and what makes them tick. By Melinda Tuhus FEATURE STORY 12 Where Are They Now? Our cultural reporter takes a look back upon some of our favorite Connecticut celebrities of yore, then brings us up to date on their whereabouts and/or current projects. By Christopher Arnott FEATURE STORY Memory Lane 20 Our cultural reporter looks at what major anniversaries are coming up in 2014, exploring a rich past in the process. By Christopher Arnott WHEELS 22 A Review of the 2015 Audi A3 Our car reviewer checks out the newly redesigned and highly regarded 24 Audi A3—and joins the chorus singing its praises. 24 By Ellis Parker PHILANTHROPY 24 Twin Tales of Generosity Our writer takes a look at two charities that the Hoffman Auto Group loves to support: the Carmen & Frank Mangini (CFM) Foundation and its annual Football Fundamentals Mini-Camp, and The Hole in the Wall Gang Camp (HITWGC) in Ashford. By Rebecca Cretella HAPPENINGS 31 Greater Hartford Spring/Summer Calendar of Events By Robert Bailin ENGINEERED FOR DRIVERS, WELCOME INSIDE AND OUT VOLUME IX, Number 1 TO OUR SPRING/SUMMER ISSUE OF DECADES! HOFFMAN AUTO GROUP Jeffrey S. -

Prepared by Evan Brown Studio Co

Prepared by Evan Brown Studio Co-Executive Silver Screen Cinema Studios 2578 Cassidy Circle West Jordan, Utah (801) 232-0431 [email protected] www.silverscreencinemastudios.com 14 MAY 2019 Confidentiality Agreement The undersigned reader acknowledges that information provided by Silver Screen Cinema Studios in this business plan is confidential; therefore, reader agrees not to disclose it without the express permission of Silver Screen Cinema Studios. It is acknowledged by reader that information to be furnished in this business plan is in all respects confidential in nature, other than information which is in the public domain through other means and that any disclosure of same by reader, may cause serious harm or damage to Silver Screen Cinema Studios. Upon request, this document is to be immediately returned to Evan Brown at given address. ________________________ Signature ________________________ Name (printed) ________________________ Date EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PHASE 1 SYNOPSIS Due to recent tax credits and tax cuts, investors are shouldering less and less risk with movies. This type of opportunity has never happened before and is only open for a short period of time. Now’s the time for you to become part of Hollywood. Also, there is more and more demand from audiences and media consumers. They want content. They don’t care if the content comes from Universal Studios, Disney, Warner Brothers, Netflix, YouTube or an independent studio such as Silver Screen Cinema Studios. As long as content is available and good, they’ll watch it – and on any screen. Distribution avenues have also opened up due to Technological improvements. Theatrical Distribution (domestic and foreign) is longer the realm of the large studios. -

Sound of Money

Wishing you a happy and safe Easter LEESBURG, FLORIDA Sunday, April 20, 2014 www.dailycommercial.com SOFTBALL: Lake-Sumter State BOMB SCARE: Four suspicious College wraps up homestand, B1 packages detonated at Lowe’s, A3 Closing Boston amid bomber hunt was ‘tough’ BOB SALSBERG Associated Press BOSTON MARATHON BOSTON — Several WHEN: Monday at days after the Boston 9:32 a.m. (Women’s Marathon bombing, Elite) and 10 a.m. Gov. Deval Patrick re- (Men’s Elite) ceived a call in the pre- WHERE: Boston, Mass. dawn hours from a top WATCH: Universal aide telling him that Sports Network police officers outside LIVE STREAM: Watch- the city had just en- Live.BAA.org gaged in a ferocious gun battle with the two Shelter in place. men suspected of set- And for the better ting the bombs and BRETT LE BLANC / DAILY COMMERCIAL part of April 19, 2013, Chip Simpson, a 58-year-old salesman at Gator Harley-Davidson in Leesburg rearranges motorcycles on the showroom floor that one was dead and the other had fled. nearly everyone did. in preparation for BikeFest on Friday. John Malik Jr., owner of Gator Harley, said he expects to sell about 60 motorcycles On what otherwise over the BikeFest weekend. Within hours, Patrick shut down the region’s would be a normal LEESBURG public transportation weekday, people stayed system and made a re- home. Stores in Boston quest of more than 1 were shuttered, streets million greater Boston deserted and an eerie Sound of money residents: SEE HUNT | A2 For merchants, the roar of motorcycles means profit THERESA CAMPBELL and dance by the per capita AUSTIN FULLER | Staff Writers spending by out-of- [email protected] towners and applying hen 100,000 bik- a complex “multipli- ers and visi- er” that assumes every tors descend on dollar spent radiates W throughout the com- downtown Leesburg next week for the 18th munity. -

Deadline Nears to Purchase Park of Honor Flags by LORI SZEPELAK Flags Are Now Available for Pur- Camp Scholarships to Local Youth,” Correspondent Chase Until Oct

TONIGHT: Showers late. Low of 47. The Westfield News Search for The Westfield News Westfield350.com The WestfieldNews Serving Westfield, Southwick, and surrounding Hilltowns “TIME IS THE ONLY WEATHER CRITIC WITHOUT TONIGHT AMBITION.” Partly Cloudy. JOHN STEINBECK Low of 55. www.thewestfieldnews.com VOL. 86 NO. 151 TUESDAY, JUNE 27, 2017 75 cents $1.00 THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3, 2019 VOL. 88 NO. 232 Deadline nears to purchase Park of Honor flags By LORI SZEPELAK Flags are now available for pur- camp scholarships to local youth,” Correspondent chase until Oct. 18 by sending a said Brown. “There is no financial WESTFIELD — Keepsake flags check for $30 for one flag or $100 for requirement for these scholarships, will once again grace the front lawn four flags to Westfield Kiwanis only that a parent or grandparent has of the Westfield Middle School next Foundation, P.O. Box 773, Westfield, served.” month during the Kiwanis Club of MA 01086-0522. A form on the Row upon row of 3’ x 5’ American Westfield’s annual “To Serve and Kiwanis Club website must be com- flags will be on display from Nov. Protect Park of Honor.” pleted and included with the check. 2-30. A brief ceremony to kick off the “It is a way to recognize and honor “I have two brothers that served in Park of Honor will be observed Nov. those military personnel that are serv- the military and currently my son and 2 at 11 a.m. ing or have served our country, along nephew are firefighters and they have Area residents are welcome and with the police departments, first been honored with a flag in the Park encouraged to walk among the flags responders and fire departments that of Honor,” said Sposito, who has during the month’s presentation, protect our community every day,” been a Kiwanian for nine years. -

Lesley& Jasmin's We Dding

YO U' RE IN VI TE D BY TH E BR ID ES ! Lesley& Jasmin 's We dding Oc tober 17,2020 |10 AM Ce remo ny:Simmo ns Ch apel Re ception :AllG ood Re staurant RS VP toClaudia at123467890 OPENING REMARKS BY ALEC BALDWIN REMARKS BY SARAH ARISON Founding Member, Americans for the Arts Co-Chair, National Arts Awards 2019 Artists Committee PERFORMANCE NATIONAL WELCOME FROM CAROLYN National YoungArts Foundation Alumni CLARK POWERS Musical Direction by Jake Goldbas ARTS Chair, National Arts Awards PHILANTHROPY IN THE AWARDS MARINA KELLEN FRENCH ARTS AWARD OUTSTANDING CONTRIBUTIONS The Honorable Earle I. Mack MONDAY, TO THE ARTS AWARD Presented by Governor George Pataki Ben Folds OCTOBER 21 Presented by Jon Batiste TED ARISON YOUNG ARTIST AWARD Ben Platt ARTS EDUCATION AWARD CMA Foundation CAROLYN CLARK POWERS LIFETIME FEATURED ART Accepted by Tiffany Kerns, ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Executive Director Luchita Hurtado Presented by Chris Young Presented by Zoe Saldana Luchita Hurtado (journal cover and stage) REMARKS BY ROBERT L. LYNCH Encounter, 1971 CLOSING REMARKS Oil on canvas President and CEO of Julie C. Muraco 50" x 94" Americans for the Arts Courtesy of the artist Chair, Americans for the Arts and Hauser & Wirth Board of Directors DINNER Luchita Hurtado (lobby gallery) Untitled, 2019 Ink and oil on paper 29 3/4" x 22" Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth 1 We are pleased to welcome you to the 2019 presentation of the Americans for the Arts GREETINGS National Arts Awards. It is altogether fitting that we take time each year to celebrate the extraordinary achievements of those individuals who are devoted to enriching our country’s FROM THE cultural landscape, via their own indelible artistry or committed philanthropic leadership. -

Shakespeare on Film and Television in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

SHAKESPEARE ON FILM AND TELEVISION IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by Zoran Sinobad January 2012 Introduction This is an annotated guide to moving image materials related to the life and works of William Shakespeare in the collections of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. While the guide encompasses a wide variety of items spanning the history of film, TV and video, it does not attempt to list every reference to Shakespeare or every quote from his plays and sonnets which have over the years appeared in hundreds (if not thousands) of motion pictures and TV shows. For titles with only a marginal connection to the Bard or one of his works, the decision what to include and what to leave out was often difficult, even when based on their inclusion or omission from other reference works on the subject (see below). For example, listing every film about ill-fated lovers separated by feuding families or other outside forces, a narrative which can arguably always be traced back to Romeo and Juliet, would be a massive undertaking on its own and as such is outside of the present guide's scope and purpose. Consequently, if looking for a cinematic spin-off, derivative, plot borrowing or a simple citation, and not finding it in the guide, users are advised to contact the Moving Image Reference staff for additional information. How to Use this Guide Entries are grouped by titles of plays and listed chronologically within the group by release/broadcast date.