Biographical Sketches of the Slaves Portrayed In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B

Welcome to a free reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. As we chose this week’s reading, news stories continued to swirl about commemorative statues, plaques, street names, and institutional names that amplify white supremacy in America and in DC. We note, as the Historical Society fulfills its mission of offering thoughtful, researched context for today’s issues, that a key influence on the history of commemoration has come to the surface: the quiet, ladylike (in the anachronistic sense) role of promoters of the southern “Lost Cause” school of Civil War interpretation. Historian Michael Chornesky details how federal officials fended off southern supremacists (posing as preservationists) on how to interpret Arlington House, home of George Washington’s adopted family and eventually of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. “Confederate Island upon the Union’s ‘Most Hallowed Ground’: The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B. Chornesky. “Confederate Island” first appeared in Washington History 27-1 (spring 2015), © Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Access via JSTOR* to the entire run of Washington History and its predecessor, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, is a benefit of membership in the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. at the Membership Plus level. Copies of this and many other back issues of Washington History magazine are available for browsing and purchase online through the DC History Center Store: https://dchistory.z2systems.com/np/clients/dchistory/giftstore.jsp ABOUT THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a non-profit, 501(c)(3), community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation's capital in order to promote a sense of identity, place and pride in our city and preserve its heritage for future generations. -

Key Facts About Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis Families

Key Facts about Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis families. The George Washington Foundation The Foundation owns and operates Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation (then known as the Kenmore Association) was formed in 1922 in order to purchase Kenmore. The Foundation purchased Ferry Farm in 1996. Historic Kenmore Kenmore was built by Fielding Lewis and his wife, Betty Washington Lewis (George Washington’s sister). Fielding Lewis was a wealthy merchant, planter, and prominent member of the gentry in Fredericksburg. Construction of Kenmore started in 1769 and the family moved into their new home in the fall of 1775. Fielding Lewis' Fredericksburg plantation was once 1,270 acres in size. Today, the house sits on just one city block (approximately 3 acres). Kenmore is noted for its eighteenth-century, decorative plasterwork ceilings, created by a craftsman identified only as "The Stucco Man." In Fielding Lewis' time, the major crops on the plantation were corn and wheat. Fielding was not a major tobacco producer. When Fielding died in 1781, the property was willed to Fielding's first-born son, John. Betty remained on the plantation for another 14 years. The name "Kenmore" was first used by Samuel Gordon, who purchased the house and 200 acres in 1819. Kenmore was directly in the line of fire between opposing forces in the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 during the Civil War and took at least seven cannonball hits. Kenmore was used as a field hospital for approximately three weeks during the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. -

Carlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’S Elusive Spinet - the Washington Connection by Richard Klingenmaier

The Friends of Carlyle House Newsletter Spring 2017 “It’s a fine beginning.” CarlyleCarlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s Elusive Spinet - The Washington Connection By Richard Klingenmaier “My Sally is just beginning her Spinnet” & Co… for Miss Patsy”, dated October 12, 1761, George John Carlyle, 1766 (1) Washington requested: “1 Very good Spinit (sic) to be made by Mr. Plinius, Harpsichord Maker in South Audley Of the furnishings known or believed to have been in John Street Grosvenor Square.” (2) Although surviving accounts Carlyle’s house in Alexandria, Virginia, none is more do not indicate when that spinet actually arrived at Mount fascinating than Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s elusive spinet. Vernon, it would have been there by 1765 when Research confirms that, indeed, Sarah owned a spinet, that Washington hired John Stadler, a German born “Musick it was present in the Carlyle House both before and after Professor” to provide Mrs. Washington and her two her marriage to William Herbert and probably, that it children singing and music lessons. Patsy was to learn to remained there throughout her long life. play the spinet, and her brother Jacky “the fiddle.” Entries in Washington’s diary show that Stadler regularly visited The story of Mount Vernon for the next six years, clear testimony of Sarah Carlyle the respect shown for his services by the Washington Herbert’s family. (3) As tutor Philip Vickers Fithian of Nomini Hall spinet actually would later write of Stadler, “…his entire good-Nature, begins at Cheerfulness, Simplicity & Skill in Music have fixed him Mount Vernon firm in my esteem.” (4) shortly after George Beginning in 1766, Sarah (“Sally”) Carlyle, eldest daughter Washington of wealthy Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and married childhood friend of Patsy Custis, joined the two Custis Martha children for singing and music lessons at the invitation of Dandridge George Washington. -

Who Was George Washington?

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Who was George Washington? ** What could be controversial about George Washington? Well, you might be surprised. The recently issued 1776 Project Report [1] describes him as a peerless hero of American freedom while the San Francisco Board of Education just erased his name from school buildings because he was a slave owner and had, shall we say, a troubled relationship with native Americans. [2] Which view is true? The 1776 Project’s view, which The Heritage Foundation called “a celebration of America,” [3] or the San Francisco Board of Education’s? [4] This is only the most recent skirmish in “the history wars,” which, whether from the political right’s attempt to whitewash American history as an ever more glorious ascent or the “woke” left’s attempt to reveal every blemish, every wrong ever done in America’s name, are a political struggle for control of America’s past in order to control its future. Both competing politically correct “isms” fail to see the American story’s rich weave of human aspiration as imperfect people seek to create a more perfect union. To say they never stumble, to say they never fall short of their ideals is one sort of lie; to say they are mere hypocrites who frequently betray the very ideals they preach is another sort of lie. In reality, Americans are both – they are idealists who seek to bring forth upon this continent, in Lincoln’s phrase, “government of the people, by the people, for the people” while on many occasions tripping over themselves and falling short. -

August 6, 2003, Note: This Description Is Not the One

Tudor Place Manuscript Collection Martha Washington Papers MS-3 Introduction The Martha Washington Papers consist of correspondence related to General George Washington's death in 1799, a subject file containing letters received by her husband, and letters, legal documents, and bills and receipts related to the settlement of his estate. There is also a subject file containing material relating to the settlement of her estate, which may have come to Tudor Place when Thomas Peter served as an executor of her will. These papers were a part of the estate Armistead Peter placed under the auspices of the Carostead Foundation, Incorporated, in 1966; the name of the foundation was changed to Tudor Place Foundation, Incorporated, in 1987. Use and rights of the papers are controlled by the Foundation. The collection was processed and the register prepared by James Kaser, a project archivist hired through a National Historical Records and Publications grant in 1992. This document was reformatted by Emily Rusch and revised by Tudor Place archivist Wendy Kail in 2020. Tudor Place Historic House & Garden | 1644 31st Street NW | Washington, DC 20007 | Telephone 202-965-0400 | www.tudorplace.org 1 Tudor Place Manuscript Collection Martha Washington Papers MS-3 Biographical Sketch Martha Dandridge (1731-1802) married Daniel Parke Custis (1711-1757), son of John Custis IV, a prominent resident of Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1749. The couple had four children, two of whom survived: John Parke Custis (1754-1781) and Martha Parke Custis (1755/6-1773). Daniel Parke Custis died in 1757; Martha (Dandridge) Custis married General George Washington in 1759and joined him at Mount Vernon, Virginia, with her two children. -

Deshler-Morris House

DESHLER-MORRIS HOUSE Part of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania Sir William Howe YELLOW FEVER in the NATION'S CAPITAL DAVID DESHLER'S ELEGANT HOUSE In 1790 the Federal Government moved from New York to Philadelphia, in time for the final session of Germantown was 90 years in the making when the First Congress under the Constitution. To an David Deshler in 1772 chose an "airy, high situation, already overflowing commercial metropolis were added commanding an agreeable prospect of the adjoining the offices of Congress and the executive departments, country" for his new residence. The site lay in the while an expanding State government took whatever center of a straggling village whose German-speaking other space could be found. A colony of diplomats inhabitants combined farming with handicraft for a and assorted petitioners of Congress clustered around livelihood. They sold their produce in Philadelphia, the new center of government. but sent their linen, wool stockings, and leatherwork Late in the summer of 1793 yellow fever struck and to more distant markets. For decades the town put a "strange and melancholy . mask on the once had enjoyed a reputation conferred by the civilizing carefree face of a thriving city." Fortunately, Congress influence of Christopher Sower's German-language was out of session. The Supreme Court met for a press. single day in August and adjourned without trying a Germantown's comfortable upland location, not far case of importance. The executive branch stayed in from fast-growing Philadelphia, had long attracted town only through the first days of September. Secre families of means. -

Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves Mary Geraghty College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geraghty, Mary, "Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jk5k-gf34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAWN PLANTATION: ELEANOR PARKE CUSTIS LEWIS AND HER SLAVES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Geraghty 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -Ln 'ln ixi ;y&Ya.4iistnh A uthor Approved, December 1993 irk. a Bar hiara Carson Vanessa Patrick Colonial Williamsburg /? Jafhes Whittenburg / Department of -

WOODLAWN Other Name/Site Number

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 WOODLAWN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: WOODLAWN Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 9000 Richmond Highway Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Alexandria Vicinity: X State: Virginia County: Fairfax Code: 059 Zip Code: 22309 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 3 4 buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects 4 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 6 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 WOODLAWN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Li)E------SEEING IS BELI EVING the SURRENDER of CORNWALLIS AS [TNEVER HAPPENED

NO . 19 THE CLEMENTS LIBRARY ASSOCIATES SPRING-SUMMER 2003 COMMEMORATION OF WASHINGTON wo hundred and Washington was a demand ing person for posterit y. Nor did it help that the fifty years ago this to work for. He micro-managed his nex t two genera tions of American s November, with an employees. preferred to think of Washington as eviction notice in hand In publi c. Washington never an ideali zed . god-like figure rather from the Governor of relaxed . He was a commanding pres than as a human being. Virginia to the French ence- tall, powerful, and formidable To mark the accession of the military commander in western not someone you ever trifled with. recently do nated letter, the Cleme nts Pennsylvani a. twenty-one-year Library staff decided to old George Washington dedicate the summe r of launched a career of public 2003 to rem embering George service unsurpassed in Washington. The Director American history. He is one of has mounted a very special those relat ively few indi viduals exhibit entitled "George who perso nally changed the Washington: Getting to course of world events in very Know the Man Behind significant ways. the Image" that will run to Mr. and Mrs. Dav id B. November 21. It draws upon Walters have recently presented remarkable original letters the Clements Library with and document s, both from a marvelous. seven-page letter the Library's co llections and written by George Washington from private sources. It is in 1793. while he was President. Washington's voluminous They will be don ating other literary output-especially material s in the futu re. -

Nomination Form

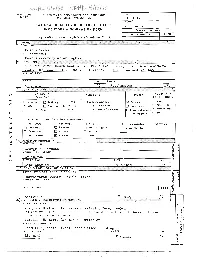

Fnnw 10-300 UNITE0 STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Virginia COUNTY. NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Northampton INVENTORY - NOMlNATlON FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER OATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) Cus tis Tombs ANOfOR HISTORIC: 1 Custis cemetery at Arlington l2. LOCATION ,, . ...,, . A A A .. ,A A,>,,. ..-.>. , ,. 5TREET ANC~~~~~~:South bank of Old Plantation Creek, .I mi. W of northern end of Rt. 644, 1.3 mi. NW of intersection of Rt. 644 and Rt, 645. Cl T V OR TOWN: STATE COUNTY' COOE - -... Yi-n la . 4 5 Northampton 131 I .' . CLASSIFICATION . ,. , . A,> : , ,% CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) --TO THE PU8LIC District a Bullding [7 Public Publlc Acquisition: Occuplad Yes: Restricted Site 0 Struclvre P"~afe IJ In Process Unoccupied a a Unrestrictrd 0 Oblect C] Both 0 Being Conrldsred Prsssrvo~lonwork In progress 0 No I PRESEN T USE (Check Ona or More os Approptlele) I Govsrnmenb Park 0 Tlonrportation 0Comments 0 Private Rerldanco Other (~paclty) George F. Parsons STREET AND NUMBER: Arlington CITY OR TOWN: I STATF: 1 I EGISTRY OF DEEDS ETC' CI TY OR TOWN. STATE Jast3LiL. .-- EREPRESENTATION-.-IN EXISTING ,. SURVEYS (TITLE OF SURVEY- m -I Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Report #65-1 D 4 DATE OF SURVEY: 1968 Federal a Stote County G Local Z DEPOSITORY FOR SUR VEV RECORDS: C Virginia Historic Landmarks CornmissLon STREET AND NUMBER: Room 1116, Ninth Street State Office CITY OR TOWN: Richmond I ~ir~inia 4 5 1 . AA,,., . ... - -<;;'', ,. ,- - . bE5CRIPTlbN *I.. I , , k. *,.. .. ~ I . ..A (Check One) Excellent Good Cj Fair a Detetiorclted 0 Rulnr 0 Unezposad CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) 0 Altered Unaltered IJ Mwed Original Site OESCRlBE THE PRESENT AN0 ORIGINAL (If known) PHYSICAL APPElRANCE Although there probably are more graves in the immediate area, visual evidence of the Custis family buriaL ground consists of two tombs surrounded by a poured concrete platform raised a few inches above ground Level. -

George Washington, Last Will and Testament, 1799, Item

___Presented by the National Humanities Center for use in a Professional Development Seminar___ Library of Congress The Last Will & Testament of George Washington July 9, 1799 Item No. Two in W.W. Abbot, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, v. 4, April-Dec. 1799. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999), and at the website The Papers of George Washington, University of Virginia Libraries (http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/will). Reproduced with permission. Item. Upon the decease of my wife, it is Univ. of Virginia Libraries my Will & desire that all the Slaves which I hold in my own right, shall receive their freedom. To emancipate them during her life, would, tho' earnestly wished by me, be attended with such insuperable difficulties on account of their intermixture by Marriages with the Dower Negroes, as to excite the most painful sensations, if not disagreeable consequences from the latter, while both descriptions are in the occupancy of the same Proprietor; it not being in my power, under the tenure by which the Dower Negros are held, to manumit them. And whereas among those who will recieve freedom according to this devise, there may be some, who from old age or bodily infirmities, and others who on account of their infancy, that will be unable to support themselves; it is my Will and desire that all who come under the first & second description shall be comfortably cloathed & fed by my heirs while they live; and that such of the latter description as have no parents Univ. of Virginia Libraries living, or if living are unable, or unwilling to provide for them, shall be bound by the Court until they shall arrive at the age of twenty five years; and in cases where no record can be produced, whereby their ages can be ascertained, the judgment of the Court, upon its own view of the subject, shall be adequate and final. -

GEORGE WASHINGTON, CAPTAIN of INDUSTRY the BANK of ENGLAND STOCK-THE BANK of the UNITED STATES by Eugene E

GEORGE WASHINGTON, CAPTAIN OF INDUSTRY THE BANK OF ENGLAND STOCK-THE BANK OF THE UNITED STATES By Eugene E. Prussing Of the Chicago .Bar [SECOND PAPER J HE marriage of Washington Custis, properly, as I am told, authen- and the Widow Custis took ticated. You will, therefore, for the fu- place January 6, r759, at ture please to address all your letters, her residence, the Whi te which relate to the affairs of the Jate House, in New Kent. The Daniel Parke Custis, to me, as by mar- great house with its six riage, I am en titled to a third part of chimney.s, betokening the wealth of its that estate, and am invested likewise with owner, IS no more--the record of the the care of the other two thirds by a de- marriage is lost-and even its exact date cree of our General Court, which I ob- rests on the casual remark of Washington tained in order to strengthen the power said to have been made to Franklin's I before had in consequence of my wife's daughter on its anniversary in 1790, administration. Franklin's birthday. I have many letters of yours in my The honeymoon was spent in visiting possession unanswered; but at present in various great houses in the neighbor- this serves only to advise you of the above hood. Besides a call at Fredericksburg, change, and at the same time to. acquaint where Mother Washington and her you, that I shall continue to make you daughter Betty dwelt, a week was spent the same consignments of tobacco as at Chatham House, on the Rappahan- usual, and will endeavor to increase them nock, the grand house of William Fitz- in proportion as I find myself and the hugh, built after plans of Sir Christopher estate benefited thereby.