The Minnesota Immigrant Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sheet: Extraterritorial Jurisdiction: a Summary

Extraterritorial jurisdiction: A summary This document contains general information. It is not legal advice. Every situation is different and other laws might apply to your situation. If you have questions, contact an attorney, visit the Department of Labor and Industry website at www.dli.mn.gov/business/workers-compensation-businesses or call the workers’ compensation hotline at 800-342-5354 and press 3. Note: This information sheet is about coverage under the Minnesota Workers’ Compensation Act for: employees injured while performing duties outside of Minnesota; and employees who regularly work outside of Minnesota who are injured while performing duties in Minnesota for the same employer. It is not about workers’ compensation coverage under the laws of other states. Injuries occuring outside the state of Minnesota An employee who is injured outside the state of Minnesota is only covered under the Minnesota Workers’ Compensation Act if the Act’s requirements for “extraterritorial application” or “temporary out-of-state employment” are met. Extraterritorial application The requirements for “extraterritorial application” are in Minnesota Statutes, section 176.041, subdivision 2. Subd. 2. Extraterritorial application. If an employee who regularly performs the primary duties of employment within this state receives an injury while outside of this state in the employ of the same employer, the provisions of this chapter shall apply to such injury. If a resident of this state is transferred outside the territorial limits of the United States as an employee of a Minnesota employer, the resident shall be presumed to be temporarily employed outside of this state while so employed. Under this statute, Minnesota workers’ compensation benefits apply if any employee who “regularly performs” the “primary duties” of employment in Minnesota is injured while working for the same employer outside of Minnesota. -

South Dakota Vs. Minnesota Trust Law Desk Reference Guide

South Dakota vs. Minnesota Trust Law Desk Reference Guide Advantage South Dakota Minnesota For over 30 years, SD has been Like many states, MN has one of the best places to locate attempted to catch up to SD by a trust. A unique and active implementing the Uniform legislative trust committee, Trust Code. However, the Trust Location (Situs) favorable Legislature and difference is still clear and governor support continues to distinct, and the state does not rank SD as a top tier trust have the stability or support jurisdiction state; as verified by that SD enjoys from the industry leaders. government. In addition to many other taxes, MN taxes its trusts. In 2018, the There is no state personal, Fielding v. Commissioner of corporate, or fiduciary income Revenue decision highlighted tax, as well as no state tax on this major difference, holding State Taxes capital gains, dividends, that a trust set up as a MN trust interest, intangibles, or any may not need to stay a resident other income. This equates to trust for tax purposes for the NO state taxes on trust income. entire length of the trust (depending on circumstances). A Dynasty Trust has unlimited possibilities because there is no Rule Against Perpetuities MN has a Rule Against The Dynasty Trust - Legacy (abolished in 1983). Dynasty Perpetuities. By statute, all Trusts avoid federal estate and non-vested interests must vest Planning for Generations income taxation on trust assets (pass) 21 years after death of an because there is no forced asset individual or 90 years after its distribution and the bonus of creation. -

Minnesota Ag News – Milk Production

United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service Minnesota Ag News – Milk Production Minnesota Field Office · 375 Jackson St, Ste 610 · St. Paul, MN 55107 (651) 728-3113 fax (855) 271-9802 · www.nass.usda.gov/mn Cooperating with the Minnesota Department of Agriculture November 18, 2020 Media Contact: Dan Lofthus Milk production in Minnesota during October 2020 totaled 846 million pounds, up 3% from the previous October according to the latest USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service – Milk Production report. The average number of milk cows during October, at 444,000 head, was the same as the previous month but down 3,000 from last year. Monthly production per cow averaged 1,905 pounds, up 60 pounds from last October. Milk Production Milk Production per Cow Minnesota: 2018-2020 Minnesota: 2018-2020 875 2,000 1,950 850 1,900 825 1,850 800 1,800 1,750 Million Million pounds 775 1,700 750 Pounds per head 1,650 725 1,600 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec 2018 2019 2020 2018 2019 2020 Milk Cows and Production – Selected States: October 2019 and 2020 Milk Cows 1 Milk Per Cow 2 Milk Production 2 State Change 2019 2020 2019 2020 2019 2020 from 2019 (1,000 head) (1,000 head) (pounds) (pounds) (million pounds) (million pounds) (percent) Arizona ...................................... 197 196 1,985 1,965 391 385 -1.5 California ................................... 1,725 1,720 1,940 1,970 3,347 3,388 1.2 Colorado .................................. -

The Minnesota Gag Law and the Fourteenth Amendment

MR, HARTMANN, a resident of Minneapolis, is enrolled in the University of Minnesota graduate school, where he is working toward a degree in American constitutional history. This is his first published article. The Minnesota GAG LAW and the Fourteenth Amendment JOHN E. HARTMANN ON JUNE 1,1931, the Supreme Court of the and the protection it affords a democratic United States handed down a decision community without the privflege this act which, according to one authority, repre seeks to limit." ^ sented "the climax of a striking evolution The origins of the Minnesota "gag law" in our Constitutional law whereby freedom are obscure. Some claim that it was spon of speech and press is at last effectively sored by a legislator intent on silencing an "nationalized'." In this decision, rendered in editor who was attacking him, and that the case of Near v. Minnesota, the court the editor died before the law could be for the first time used "the guarantee of applied to his particular publication.^ The liberty in the Fourteenth Amendment . bill was initiated in the Minnesota Senate to completely obliterate a state law."^ by Freling H. Stevens, a Minneapolis attor The law in question, which had been ney whose firm included his brother and enacted by the Minnesota legislature in his two sons. He was serving his second 1925, declared certain types of publications term as state senator, and politically he was a nuisance and provided for injunctions to a Progressive-Republican. When the bfll prevent their circulation. Of this Minnesota was introduced on March 27, 1925, as Sen measure — the first to provide for actual ate File 1181, it did not cause a furor. -

Fishing the Red River of the North

FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH The Red River boasts more than 70 species of fish. Channel catfish in the Red River can attain weights of more than 30 pounds, walleye as big as 13 pounds, and northern pike can grow as long as 45 inches. Includes access maps, fishing tips, local tourism contacts and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR GUIDE TO FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH 3 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT 4 RIVER STEWARDSHIP 4 FISH OF THE RED RIVER 5 PUBLIC ACCESS MAP 6 PUBLIC ACCESS CHART 7 AREA MAPS 8 FISHING THE RED 9 TIP AND RAP 9 EATING FISH FROM THE RED RIVER 11 CATCH-AND-RELEASE 11 FISH RECIPES 11 LOCAL TOURISM CONTACTS 12 BE AWARE OF THE DANGERS OF DAMS 12 ©2017, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources FAW-471-17 The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651-259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. This brochure was produced by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife with technical assistance provided by the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish. -

State Abbreviations

State Abbreviations Postal Abbreviations for States/Territories On July 1, 1963, the Post Office Department introduced the five-digit ZIP Code. At the time, 10/1963– 1831 1874 1943 6/1963 present most addressing equipment could accommodate only 23 characters (including spaces) in the Alabama Al. Ala. Ala. ALA AL Alaska -- Alaska Alaska ALSK AK bottom line of the address. To make room for Arizona -- Ariz. Ariz. ARIZ AZ the ZIP Code, state names needed to be Arkansas Ar. T. Ark. Ark. ARK AR abbreviated. The Department provided an initial California -- Cal. Calif. CALIF CA list of abbreviations in June 1963, but many had Colorado -- Colo. Colo. COL CO three or four letters, which was still too long. In Connecticut Ct. Conn. Conn. CONN CT Delaware De. Del. Del. DEL DE October 1963, the Department settled on the District of D. C. D. C. D. C. DC DC current two-letter abbreviations. Since that time, Columbia only one change has been made: in 1969, at the Florida Fl. T. Fla. Fla. FLA FL request of the Canadian postal administration, Georgia Ga. Ga. Ga. GA GA Hawaii -- -- Hawaii HAW HI the abbreviation for Nebraska, originally NB, Idaho -- Idaho Idaho IDA ID was changed to NE, to avoid confusion with Illinois Il. Ill. Ill. ILL IL New Brunswick in Canada. Indiana Ia. Ind. Ind. IND IN Iowa -- Iowa Iowa IOWA IA Kansas -- Kans. Kans. KANS KS A list of state abbreviations since 1831 is Kentucky Ky. Ky. Ky. KY KY provided at right. A more complete list of current Louisiana La. La. -

Minnesota Metropolitan Area

Minnesota Metropolitan Area Clear Lake Zimmerman Stanford Twp. IsantiAthens Twp. Oxford Twp. Clear Lake Twp. Orrock Twp. Chisago Lake Twp. Livonia Twp. Lent Twp. Clearwater Becker Twp. Bethel St. Francis Stacy Center City Shafer Sherburne Lindstrom Clearwater Twp. Becker 169 Linwood Twp. Chisago City 10 East Bethel Big LakeBig Lake Twp. Burns Twp. Oak Grove Wyoming Twp. Franconia Twp. Silver Creek Twp. Elk River Wyoming Chisago Monticello Corinna Twp. Anoka Monticello Twp. Columbus Twp. Otsego Twp. Ramsey Andover Ham Lake Forest Lake New Scandia Twp. Maple Lake Twp. Albertville 35 Maple Lake Anoka Albion Twp. Buffalo Twp. St. Michael Rogers Marine on St. Croix Dayton Buffalo Hassan Twp. Chatham Twp. Coon Rapids Champlin Blaine Hanover Lino LakesCenterville Hugo May Twp. 169 Circle Pines Lexington Washington Rockford Twp. Osseo Spring Lake Park Wright Corcoran Maple Grove Brooklyn Park Mounds View White Bear Twp. Marysville Twp. Greenfield North Oaks Dellwood Stillwater Twp. Rockford Fridley Shoreview Grant Waverly 94 Montrose Hennepin Brooklyn Center Arden Hills Gem LakeBirchwood Village New Brighton Loretto White Bear LakeMahtomedi Stillwater Columbia Heights Vadnais Heights Delano New Hope Franklin Twp. Medina Crystal Pine Springs Oak Park Heights Woodland Twp. Independence Plymouth Robbinsdale St. Anthony Little Canada Bayport Roseville MaplewoodNorth St. Paul Maple Plain 36 Baytown Twp. Medicine Lake Lauderdale Lake Elmo Long Lake Golden Valley Falcon Heights 35E Oakdale Wayzata Winsted 394 West Lakeland Twp. Watertown Orono Minneapolis Ramsey Woodland St. Louis Park St. Paul Landfall Spring Park Hollywood Twp. Watertown Twp. Minnetrista Lakeland Mound DeephavenMinnetonka Hopkins Lake St. Croix Beach Shorewood Lilydale St. Bonifacius Tonka BayGreenwood West St. -

2020-2021 Minnesota-North Dakota Application for Reciprocity Benefits

2020-2021 MINNESOTA-NORTH DAKOTA APPLICATION FOR RECIPROCITY BENEFITS MINNESOTA OFFICE OF HIGHER EDUCATION NORTH DAKOTA UNIVERSITY SYSTEM GENERAL INFORMATION AND INSTRUCTIONS Minnesota-North Dakota Tuition Reciprocity Program 2020-2021 Academic year (Fall 2020-Spring/Summer 2021) ✓ To avoid delay, applications must be mailed directly to the appropriate state agency by the applicant ✓ The application must be completed in ink or typed ✓ APPLICATION FOR RECIPROCITY IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF THE INDIVIDUAL HOW TO APPLY: Complete this application IN FULL and sign the certification. Mail the completed application DIRECTLY to the higher education agency located in the state of your residence. Reciprocity recipients who earned credits during the 2019-2020 academic year will automatically have benefits renewed for 2020-2021 at the institution reporting credits for the student during the 2019-2020 academic year. Therefore, these students do NOT need to complete a reciprocity application for the 2020-2021 academic year. If your current institution has not received notification of your renewal status by November 1, 2020, please contact the administering agency in your state of residence. APPLICATION DEADLINES COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES: The application for tuition reciprocity must be correctly completed and postmarked by the last day of classes in the term for which benefits are needed. The application deadline, except those in vocational and technical programs, is the last day of classes at the institution you are or will be attending in the term that benefits are required. Applications will not be processed retroactively. If you wish to participate in the program for the entire academic year, your application must be correctly completed and postmarked by the last day of scheduled classes in the fall term at the institution you are or will be attending. -

Nebraska's Big Ten History

100 2017-18 NEBRASKA WOMEN'S BASKETBALL NEBRASKA'S BIG TEN HISTORY Although Nebraska competed for the first time as a member of the Big Ten Conference in 2011-12, the Huskers have a relatively substantial history playing against Big Ten opponents. Nebraska's first-ever meeting with a Big Ten school came with a thrilling 68-67 overtime victory over Minnesota on Dec. 30, 1977. Two weeks later, the Huskers improved to 2-0 against the Big Ten with a 71-63 victory over Iowa at the Jennies Classic in Warrensburg, Mo., on Jan. 13, 1978. The following season, Nebraska improved to 3-0 against the Big Ten with a narrow 59-57 victory over Minnesota at the Devaney Center on Nov. 28, 1978. Overall, the Huskers carry an 88-78 all-time record against Big Ten opposition after their first six seasons of Big Ten Conference competition. Nebraska is 64-49 against Big Ten foes in its first six seasons in the conference, including 56-44 in Big Ten regular-season play. The Huskers captured the 2014 Big Ten Tournament title by going 3-0 in Indianapolis. The Huskers are 8-5 all-time in the Big Ten Tournament and 6-3 at Bankers Life Fieldhouse in Indianapolis. The Huskers are 32-30 on the road in Big Ten play in their first six Big Ten seasons. Nebraska's Big Ten Series History vs. Illinois (Nebraska leads, 10-5) Lincoln: Nebraska leads, 5-1 (last, Nebraska 73, Illinois 57, Jan. 10, 2016) Champaign-Urbana: Nebraska leads, 4-2 (last, Illinois 79, Nebraska 70, March 1, 2017) Neutral: Illinois leads, 2-1 (last, Illinois 79, Nebraska 70, March 1, 2017) Last Meeting: Illinois 79, Nebraska 70, March 1, 2017 (Lincoln) First Meeting: Nebraska 89, Illinois 86, March 3, 1982 vs. -

APPLICANT's ACKNOWLEDGMENT and AUTHORIZATION ADDITIONAL NOTICES to CALIFORNIA, MINNESOTA, OKLAHOMA, and NEW YORK APPLICANTS Ca

DISCLOSURE/AUTHORIZATION FORM NOTICE TO APPLICANT REGARDING BACKGROUND CHECK ADDITIONAL NOTICES TO CALIFORNIA, MINNESOTA, OKLAHOMA, In order to safeguard the youth in our care, the Boy Scouts of America will procure consumer AND NEW YORK APPLICANTS California reports on you in connection with your application to serve as a volunteer, and the Boy Scouts of America may procure additional consumer reports at any time during your service as a Under California law, the consumer reports described above that the Boy Scouts of America volunteer in order to evaluate your continued suitability for volunteer service. The Boy Scouts will procure on you are defined as investigative consumer reports. These reports will be of America has contracted with LexisNexis, a consumer reporting agency, to provide the procured in connection with your application to serve as a volunteer, and additional reports consumer reports. LexisNexis may be contacted by mail at LexisNexis, 1000 may be procured at any time during your service as volunteer in order to evaluate your Alderman Drive, Alpharetta, GA 30005 or by telephone at 800-845-6004. continued suitability for volunteer service. The reports may include information on your character, general reputation, personal characteristics, and mode of living. The consumer reports may contain information bearing on your character, general reputation, personal characteristics, and mode of living. The types of information that Under section 1786.22 of the California Civil Code, you may inspect the file maintained on you may be obtained include but are not limited to Social Security number verification, sex by LexisNexis, during normal business hours and with proper identification. -

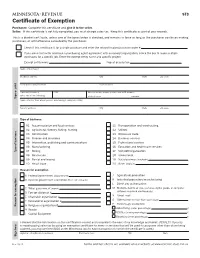

ST3, Certificate of Exemption, to You Must Apply for and Receive Exempt Claim the Following Exemptions

ST3 Certificate of Exemption Purchaser: Complete this certificate and give it to the seller. Seller: If this certificate is not fully completed, you must charge sales tax. Keep this certificate as part of your records. This is a blanket certificate, unless one of the boxes below is checked, and remains in force as long as the purchaser continues making purchases, or until otherwise cancelled by the purchaser. Check if this certificate is for a single purchase and enter the related invoice/purchase order # . If you are a contractor and have a purchasing agent agreement with an exempt organization, check the box to make multiple purchases for a specific job. Enter the exempt entity name and specific project: Exempt entity name Project description Name of purchaser Business address City State Zip code Purchaser’s tax ID number State of issue If no tax ID number, FEIN Driver’s license number/State issued ID number enter one of the following: state of issue number Type or print Type Name of seller from whom you are purchasing, leasing or renting Seller’s address City State Zip code Type of business. 10 Accommodation and food services 11 Transportation and warehousing 02 Agricultural, forestry, fishing, hunting 12 Utilities 03 Construction 31 Wholesale trade 04 Finance and insurance 41 Business services 05 Information, publishing and communications 51 Professional services 06 Manufacturing 61 Education and health-care services Type of business Type 07 Mining 17 Nonprofit organization 08 Real estate 18 Government 09 Rental and leasing 91 Not a business (explain) 01 Retail trade 20 Other (explain) Reason for exemption. -

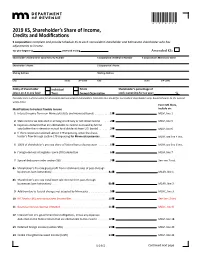

2019 KS, Shareholder's Share of Income, Credits and Modifications

*197411* 2019 KS, Shareholder’s Share of Income, Credits and Modifications S corporation: Complete and provide Schedule KS to each nonresident shareholder and Minnesota shareholder who has adjustments to income. Tax year beginning , 2019 and ending Amended KS: Shareholder’s Federal ID or Social Security Number S Corporation’s Federal ID Number S Corporation’s Minnesota Tax ID Shareholder’s Name S Corporation’s Name Mailing Address Mailing Address City State ZIP Code City State ZIP Code Entity of Shareholder Individual Estate Shareholder’s percentage of (place an X in one box): stock ownership for tax year: Trust Exempt Organization % Calculate lines 1–25 the same for all resident and nonresident shareholders. Calculate lines 26–40 for nonresident shareholders only. Round amounts to the nearest whole dollar. Form M1 filers, Modifications to Federal Taxable Income include on: 1 Interest income from non-Minnesota state and municipal bonds . 1 M1M, line 1 2 State income tax deducted in arriving at ordinary or net rental income . 2. M1M, line 5 3 Expenses deducted that are attributable to income not taxed by Minne- sota (other than interest or mutual fund dividends from U .S . bonds) . 3 M1M, line 6 4 If the S corporation elected section 179 expensing, enter the share- holder’s flow-through section 179 expensing for Minnesota purposes . 4 M1M, see line 4 inst . 5 100% of shareholder’s pro rata share of federal bonus depreciation . 5. M1M, see line 3 inst . 6 Foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction . 6. M1M, line 7 7 Special deduction under section 965 . 7 See line 7 inst.