The Making of World's Largest Journal in Systematic Botany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Plant Science Journals

Ecology, Evolutionary Biology and Plant Science Journals START YOUR JOURNEY HERE... www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell ● Access to must-have content i n Conservation, Ecology, Zoology and Entomology, Plant Science and Evolutionary Biology ● Publications span the entire spectrum of these disciplines ● Partnerships with key international scholarly societies 13310_5.indd 1 12/8/08 18:51:42 NEW JOURNALS CONSERVATION Animal Conservation Conservation Letters Published on behalf of The Zoological Society of A journal of the Society for Conservation Biology Wiley-Blackwell is pleased to announce the addition of these journals to our list in 2008: London Edited by RICHARD M. COWLING, MICHAEL B. Edited by GUY COWLISHAW, TRENTON GARNER, MASCIA, HUGH POSSINGHAM, WILLIAM J. Conservation Letters Journal of Industrial Ecology MATTHEW GOMPPER, TODD KATZNER, KAREN SUTHERLAND and COREY BRADSHAW Published on behalf of the Society for Conservation Published for Yale University on behalf of the MOCK and STEPHEN REDPATH www.blackwellpublishing.com/conl Biology School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. Impact Factor®: 2.495 The offi cial journal of the International Society Edited by RICHARD M. COWLING, MICHAEL B. www.blackwellpublishing.com/acv MASCIA, HUGH POSSINGHAM, WILLIAM J. for Industrial Ecology SUTHERLAND and COREY BRADSHAW Diversity and Distributions Edited by REID LIFSET Edited by DAVID M. RICHARDSON www.blackwellpublishing.com/conl Impact Factor®: 1.962 Aquatic Conservation Impact Factor®: 2.965 www.blackwellpublishing.com/jie Marine and Freshwater -

The Promise of Next-Generation Taxonomy

Megataxa 001 (1): 035–038 ISSN 2703-3082 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/mt/ MEGATAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 2703-3090 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/megataxa.1.1.6 The promise of next-generation taxonomy MIGUEL VENCES Zoological Institute, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Mendelssohnstr. 4, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0747-0817 Documenting, naming and classifying the diversity and concepts. We should meet three main challenges, of life on Earth provides baseline information on the using new technological developments without throwing biosphere, which is crucially important to understand and the well-tried and successful foundations of Linnaean mitigate the global changes of the Anthropocene. Since nomenclature overboard. Linnaeus, taxonomists have named about 1.8 million species (Roskov et al. 2019) and continue doing so at 1. Fully embrace cybertaxonomy, machine learning a rate of about 15,000–20,000 species per year (IISE and DNA taxonomy to ease, not burden the workflow 2011). Natural history collections—museums, herbaria, of taxonomists. culture collections and others—hold billions of collection specimens (Brooke 2000) and have teamed up to Computer power and especially, DNA sequencing capacity assemble a cybertaxonomic infrastructure that mobilizes increases faster than exponentially (e.g., Rupp 2018) metadata and images of voucher specimens, now even and new technologies offer unprecedented opportunities at the scale of digitizing entire collections of millions for classifying specimens based on molecular evidence of insect or herbaria vouchers in automated imaging or image analysis. Yet, the vast majority of species lines (e.g., Tegelberg et al. -

Taxonomic Novelties in the Fern Genus Tectaria (Tectariaceae)

Phytotaxa 122 (1): 61–64 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.122.1.3 Taxonomic novelties in the fern genus Tectaria (Tectariaceae) HUI-HUI DING1,2, YI-SHAN CHAO3 & SHI-YONG DONG1* 1 Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China. 2 Graduate University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China. 3 Division of Botanical Garden, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Taipei 10066, Taiwan. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The misapplication of the name Tectaria griffithii is corrected, which results in the revival of T. multicaudata and the proposal of a new combination (T. multicaudata var. amplissima) and two new synonyms (T. yunnanensis and T. multicaudata var. singaporeana). For the reduction of Psomiocarpa and Tectaridium (previously monotypic genera) into Tectaria, T. macleanii (new combination) and T. psomiocarpa (new name) are proposed as new combinations. In addition, the new name Tectaria subvariolosa is put forward to replace a later homonym (T. stenosemioides). Key words: nomenclature, Psomiocarpa, taxonomy, Tectaridium Introduction Tectaria Cavanilles (1799) (Tectariaceae) is a fern genus frequent in tropical regions, with most species growing terrestrially in rain forests. This group is remarkable for its extremely diverse morphology, and the estimated number of species ranges from 150 (Tryon & Tryon 1982; Kramer 1990) to 210 (Holttum 1991a). Holttum (1991a) recognized 105 species in Tectaria from Malesia and presumed that SE Asia is its center of origin. -

Dr. S. R. Yadav

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME : SHRIRANG RAMCHANDRA YADAV DESIGNATION : Professor INSTITUTE : Department of Botany, Shivaji University, Kolhapur 416004(MS). PHONE : 91 (0231) 2609389, Mobile: 9421102350 FAX : 0091-0231-691533 / 0091-0231-692333 E. MAIL : [email protected] NATIONALITY : Indian DATE OF BIRTH : 1st June, 1954 EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: Degree University Year Subject Class B.Sc. Shivaji University 1975 Botany I-class Hons. with Dist. M.Sc. University of 1977 Botany (Taxonomy of I-class Bombay Spermatophyta) D.H.Ed. University of 1978 Education methods Higher II-class Bombay Ph.D. University of 1983 “Ecological studies on ------ Bombay Indian Medicinal Plants” APPOINTMENTS HELD: Position Institute Duration Teacher in Biology Ruia College, Matunga 16/08/1977-15/06/1978 JRF (UGC) Ruia College, Matunga 16/06/1978-16/06/1980 SRF (UGC) Ruia College, Matunga 17/06/1980-17/06/1982 Lecturer J.S.M. College, Alibag 06/12/1982-13/11/1984 Lecturer Kelkar College, Mulund 14/11/1984-31/05/1985 Lecturer Shivaji University, Kolhapur 01/06/1985-05/12/1987 Sr. Lecturer Shivaji University, Kolhapur 05/12/1987-31/01/1993 Reader and Head Goa University, Goa 01/02/1993-01/02/1995 Sr. Lecturer Shivaji University, Kolhapur 01/02/1995-01/12/1995 Reader Shivaji University, Kolhapur 01/12/1995-05/12/1999 Professor Shivaji University, Kolhapur 06/12/1999-04/06/2002 Professor University of Delhi, Delhi 05/06/2002-31/05/2005 Professor Shivaji University, Kolhapur 01/06/2005-31/05/2014 Professor & Head Department of Botany, 01/06/2013- 31/05/2014 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Professor & Head Department of Botany, 01/08/ 2014 –31/05/ 2016 Shivaji University, Kolhapur UGC-BSR Faculty Department of Botany, Shivaji 01/06/2016-31/05/2019 Fellow University, Kolhapur. -

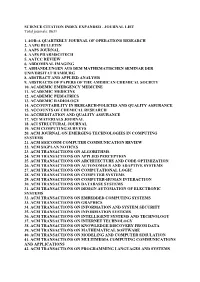

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Corrections to Phytotaxa 19: Linear Sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns

Phytotaxa 28: 50–52 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Correction PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) Corrections to Phytotaxa 19: Linear sequence of lycophytes and ferns MAARTEN J.M. CHRISTENHUSZ1 & HARALD SCHNEIDER2 1Botany Unit, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Postbox 4, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, SW7 5BD London, U.K. E-mail: [email protected] After the publication of our A linear sequence of extant families and genera of lycophytes and ferns (Christenhusz, Zhang & Schneider 2011), a couple of errors were brought to our attention: Platyzoma placed in Pteris (Pteridaceae), and correcting erroneous combinations made in Pteris of Gleichenia species. In the New Combinations section on page 22, we attempted to provide new combinations for the genus Platyzoma R.Br., which is embedded in Pteris L. (Schuettpelz & Pryer 2007, Lehtonen 2011). When doing so, we made the unfortunate choice to follow the treatment of Platyzoma by Desvaux (1827), which included several additional species of Gleichenia, instead of the modern treatment of Platyzoma in which only the species Platyzoma microphyllum Brown (1810: 160) is included. Only that name needed to be transferred. This resulted in the creation of a number of unnecessary new names and combinations of Australasian Gleichenia, for which we apologise. We erroneously provided names in Pteris for Gleichenia dicarpa R.Br., G. alpina R.Br. and G. rupestris R.Br., which are all correctly placed in Gleichenia and not in Pteris. Therefore these new names are to be treated as synonyms. -

Taxonomy and Distribution of Non-Geniculate Coralline Red Algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) on Rocky Reefs from Ilha Grande Bay, Brazil

Phytotaxa 192 (4): 267–278 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2015 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.192.4.4 Taxonomy and distribution of non-geniculate coralline red algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) on rocky reefs from Ilha Grande Bay, Brazil FREDERICO T.S. TÂMEGA1,2*, RAFAEL RIOSMENA-RODRIGUEZ3, PAULA SPOTORNO-OLIVEIRA4 RODRIGO MARIATH2, SAMIR KHADER2 & MARCIA A.O. FIGUEIREDO2 1Instituto de Estudos do Mar Almirante Paulo Moreira, Departamento de Oceanografia, Rua Kioto 253, 28930-000, Arraial do Cabo, RJ, Brazil. 2Instituto de Pesquisa Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, Rua Pacheco Leão 915, Jardim Botânico 22460-030, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. 3Programa de Investigación en Botánica Marina, Departamento de Biología Marina, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, Apartado postal 19–B, 23080 La Paz, BCS, Mexico. 4Universidade Federal do Rio Grande, Museu Oceanográfico “Prof. Eliézer de Carvalho Rios” (MORG), Laboratório de Malacologia, 96200–580, Rio Grande, RS, Brazil. *Corresponding author. Phone (+5522) 2622–9058, 98185-7020. Email: [email protected] Abstract Non-geniculate coralline red algae are very common along the Brazilian coast occurring in a wide variety of ecosystems. Ecological surveys of Ilha Grande Bay have shown the importance of these algae in structuring benthic rocky reef environ- ments and in their structural processes. The aim of this research was to identify the species of non-geniculate coralline red algae commonly present in the shallow rocky areas of Ilha Grande Bay, Brazil. Based on morphological and anatomical observations, three species of non-geniculate coralline algae are commonly present in the area: Lithophyllum corallinae, L. -

New Combinations in Lomatium (Apiaceae, Subfamily Apioideae)

Phytotaxa 316 (1): 095–098 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2017 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.316.1.11 NEW COMBINATIONS IN LOMATIUM (APIACEAE, SUBFAMILY APIOIDEAE) MARY ANN E. FEIST1, JAMES F. SMITH2, DONALD H. MANSFIELD3, MARK DARRACH4, RICHARD P. MCNEILL5, STEPHEN R. DOWNIE6, GREGORY M. PLUNKETT7 & BARBARA L. WILSON8 1Department of Botany, Wisconsin State Herbarium, 430 Lincoln Drive, University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin 53706, USA; [email protected] 2Department of Biological Sciences, Snake River Plains Herbarium, Boise State University, Boise, Idaho 83725, USA; [email protected] 3Department of Biology, Harold M. Tucker Herbarium, The College of Idaho, Caldwell, Idaho 83605, USA; [email protected] 4Herbarium, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195, USA; [email protected], [email protected] 5 Vegetation and Ecological Restoration, Yosemite National Park, P.O. Box 700, El Portal CA 95318, USA; [email protected] 6Department of Plant Biology, 265 Morrill Hall, 505 South Goodwin Avenue, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; [email protected] 7Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics, New York Botanical Garden, 2900 Southern Blvd., Bronx, New York 10458-5126, USA; [email protected] 8 OSU Herbarium, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, 2082 Cordley Hall, Corvallis, Oregon 97331, USA; [email protected] Molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses indicate that many of the perennial endemic genera of North American Apiaceae are either polyphyletic or nested within paraphyletic groups. In light of these results, taxonomic changes are needed to ensure that ongoing efforts to prepare state, regional, and continental floristic treatments of Apiaceae reflect recent findings. -

Solidago ×Snarskisii Nothosp. Nov. (Asteraceae) from Lithuania and Its Position in the Infrageneric Classification of the Genus

Phytotaxa 253 (2): 147–155 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.253.2.4 Solidago ×snarskisii nothosp. nov. (Asteraceae) from Lithuania and its position in the infrageneric classification of the genus Zigmantas gudžinskas1,2 & Egidijus žalnEravičius1,3 1Nature Research Centre, Institute of Botany, Žaliųjų Ežerų Str. 49, LT-08406 Vilnius, Lithuania 2e-mail: [email protected]; 3e-mail: [email protected] Abstract A natural hybrid between the native Solidago virgaurea and the alien invasive S. gigantea, recorded in south lithuania, is described as S. ×snarskisii nothosp. nov. A new nothosubsection, Solidago sect. Solidago nothosubsect. Triplidago notho- subsect. nov., is proposed to accommodate this hybrid and S. ×niederederi. Key words: alien species, fertility, hybridization, native species, nothospecies, nothosubsection, reproduction. Introduction The process of natural hybridization may produce genotypes that establish new evolutionary lineages (Arnold & Hodges 1995). Judging by the wide distribution of allopolyploidy among plants, many species might be of direct hybrid origin or descended from a hybrid species in the recent past (Soltis & Soltis 1995). Interspecific hybridization between a native and an invading plant species or two invading species results in a new taxon (Abbot 1992). Further hybridization of new taxa with native ones can lead to the loss of genetic integrity of native populations (Huxel 1999, kaljund & leht 2013). For example, an extent of hybridization between native and alien species has been evaluated in Germany. The study revealed that 75 hybrids have been already registered and 59 further hybrids can be detected as both parental species occur in the country (Bleeker et al. -

Cyatheaceae) in China

Phytotaxa 449 (1): 015–022 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.449.1.2 The true identity of the Gymnosphaera gigantea (Cyatheaceae) in China SHI-YONG DONG1,2,5*, A.K.M. KAMRUL HAQUE3,6 & MOHAMMAD SAYEDUR RAHMAN4,7 1 Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China. 2 Center of Conservation Biology, Core Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China. 3 Department of Botany, Mohammadpur Government College, Dhaka, Bangladesh. 4 Bangladesh National Herbarium, Dhaka-1216, Bangladesh. 5 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8449-7856 6 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6276-8424 7 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3589-1846 *Author for correspondence: �[email protected] Abstract The scaly tree fern widely accepted as Gymnosphaera gigantea in China is demonstrated to be a separate species, G. henryi. Our field observations show that G. henryi is a good species and is readily recognized by the combination of stipe bearing 2-rowed scales throughout, pinnae being sessile, and most or at least lower pinnae being opposite on rachis. However, G. gigantea is different in stipe without 2-rowed scales above the base and pinnae being more or less petiolate and mostly alternate on rachis. Gymnosphaera henryi is common in southern and southwestern China and Vietnam and is currently known also in Laos and Myanmar. -

Karyomorphometric Analysis of Fritillaria Montana Group in Greece

COMPARATIVE A peer-reviewed open-access journal CompCytogen 10(4): 679–695Karyomorphometric (2016) analysis of Fritillaria montana group in Greece 679 doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i4.10156 RESEARCH ARTICLE Cytogenetics http://compcytogen.pensoft.net International Journal of Plant & Animal Cytogenetics, Karyosystematics, and Molecular Systematics Karyomorphometric analysis of Fritillaria montana group in Greece Sofia Samaropoulou1, Pepy Bareka1, Georgia Kamari2 1 Laboratory of Systematic Botany, Faculty of Crop Science, Agricultural University of Athens, Iera Odos 75, 118 55 Athens, Greece 2 Botanical Institute, Section of Plant Biology, Department of Biology, University of Patras, 265 00 Patras, Greece Corresponding author: Pepy Bareka ([email protected]) Academic editor: G. Karlov | Received 12 August 2016 | Accepted 16 October 2016 | Published 1 December 2016 http://zoobank.org/B62D5109-1CDC-4CE3-BFD3-19BE113A32DE Citation: Samaropoulou S, Bareka P, Kamari G (2016) Karyomorphometric analysis of Fritillaria montana group in Greece. Comparative Cytogenetics 10(4): 679–695. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i4.10156 Abstract Fritillaria Linnaeus, 1753 (Liliaceae) is a genus of geophytes, represented in Greece by 29 taxa. Most of the Greek species are endemic to the country and/or threatened. Although their classical cytotaxonomic studies have already been presented, no karyomorphometric analysis has ever been given. In the present study, the cytological results of Fritillaria montana Hoppe ex W.D.J. Koch, 1832 group, which includes F. epirotica Turrill ex Rix, 1975 and F. montana are statistically evaluated for the first time. Further indices about interchromosomal and intrachromosomal asymmetry are given. A new population of F. epirotica is also investigated, while for F. montana, a diploid individual was found in a known as triploid population. -

Cordyceps Yinjiangensis, a New Ant-Pathogenic Fungus

Phytotaxa 453 (3): 284–292 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.453.3.10 Cordyceps yinjiangensis, a new ant-pathogenic fungus YU-PING LI1,3, WAN-HAO CHEN1,4,*, YAN-FENG HAN2,5,*, JIAN-DONG LIANG1,6 & ZONG-QI LIANG2,7 1 Department of Microbiology, Basic Medical School, Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang, Guizhou 550025, China. 2 Institute of Fungus Resources, Guizhou University, Guiyang, Guizhou 550025, China. 3 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9021-8614 4 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7240-6841 5 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8646-3975 6 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2583-5915 7 [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2867-2231 *Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Ant-pathogenic fungi are mainly found in the Ophiocordycipitaceae, rarely in the Cordycipitaceae. During a survey of entomopathogenetic fungi from Southwest China, a new species, Cordyceps yinjiangensis, was isolated from the ponerine. It differs from other Cordyceps species by its ant host, shorter phialides, and smaller septate conidia formed in an imbricate chain. Phylogenetic analyses based on the combined datasets of (LSU+RPB2+TEF) and (ITS+TEF) confirmed that C. yinjiangensis is distinct from other species. The new species is formally described and illustrated, and compared to similar species. Keywords: 1 new species, Cordyceps, morphology, phylogeny, ponerine Introduction The ascomycete genus Cordyceps sensu lato (sl) consists of more than 600 fungal species.