Nongeniculate Coralline Red Algae (Rhodophyta: Corallinales) in Coral Reefs from Northeastern Brazil and a Description of Neogoniolithon Atlanticum Sp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonization and Growth of Crustose Coralline Algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) on the Rocas Atoll

BRAZILIAN JOURNAL OF OCEANOGRAPHY, 53(3/4):147-156, 2005 Colonization and growth of crustose coralline algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) on the Rocas Atoll Alexandre Bigio Villas Bôas1*; Marcia A. de O.Figueiredo 2 & Roberto Campos Villaça 1 1Universidade Federal Fluminense (Caixa Postal 100644, 24001-970Niterói, RJ, Brasil) 2Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro (Rua Pacheco Leão 915, 22460-030 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brasil) *[email protected] A B S T R A C T Crustose coralline algae play a fundamental role in reef construction all over the world. The aims fo this study were to identify and estimate the abundance of the dominant crustose coralline algae in shallow reef habitats, measuring their colonization, growth rates and productivity. Crusts sampled from different habitats were collected on leeward and windward reefs. Discs made of epoxy putty were fixed on the reef surface to follow coralline colonization and discs containing the dominant coralline algae were fixed on different habitats to measure the crusts’ marginal growth. The primary production experiments followed the clear and dark bottle method for dissolved oxygen reading. Porolithon pachydermum was confirmed as the dominant crustose coralline alga on the Rocas Atoll. The non-cryptic flat form of P. pachydermum showed a faster growth rate on the leeward than on the windward reef. This form also had a faster growth rate on the reef crest (0.05 mm.day-1) than on the reef flat (0.01 mm.day-1). The cryptic protuberant form showed a trend, though not significant, towards a faster growth rate on the reef crest and in tidal pools than on the reef flat. -

The Promise of Next-Generation Taxonomy

Megataxa 001 (1): 035–038 ISSN 2703-3082 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/mt/ MEGATAXA Copyright © 2020 Magnolia Press Correspondence ISSN 2703-3090 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/megataxa.1.1.6 The promise of next-generation taxonomy MIGUEL VENCES Zoological Institute, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Mendelssohnstr. 4, 38106 Braunschweig, Germany �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0747-0817 Documenting, naming and classifying the diversity and concepts. We should meet three main challenges, of life on Earth provides baseline information on the using new technological developments without throwing biosphere, which is crucially important to understand and the well-tried and successful foundations of Linnaean mitigate the global changes of the Anthropocene. Since nomenclature overboard. Linnaeus, taxonomists have named about 1.8 million species (Roskov et al. 2019) and continue doing so at 1. Fully embrace cybertaxonomy, machine learning a rate of about 15,000–20,000 species per year (IISE and DNA taxonomy to ease, not burden the workflow 2011). Natural history collections—museums, herbaria, of taxonomists. culture collections and others—hold billions of collection specimens (Brooke 2000) and have teamed up to Computer power and especially, DNA sequencing capacity assemble a cybertaxonomic infrastructure that mobilizes increases faster than exponentially (e.g., Rupp 2018) metadata and images of voucher specimens, now even and new technologies offer unprecedented opportunities at the scale of digitizing entire collections of millions for classifying specimens based on molecular evidence of insect or herbaria vouchers in automated imaging or image analysis. Yet, the vast majority of species lines (e.g., Tegelberg et al. -

PROGRAMME 4 - 7 July 2017 • Boardwalk Convention Centre • Port Elizabeth • South Africa

SAMssPORT ELIZABETH 2017 THE 16TH SOUTHERN AFRICAN MARINE SCIENCE SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME 4 - 7 July 2017 • www.samss2017.co.za Boardwalk Convention Centre • Port Elizabeth • South Africa Theme: Embracing the blue l Unlocking the Ocean’s economic potential whilst maintaining social and ecological resilience SAMSS is hosted by NMMU, CMR and supported by SANCOR WELCOME PLENARY SPEAKERS It is our pleasure to welcome all SAMSS 2017 participants on behalf of the ROBERT COSTANZA - The Australian National University - Australia Institute for Coastal and Marine Research at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University and the city of Port Elizabeth. NMMU has a long tradition of marine COSTANZA has an H-index above 100 and >60 000 research and its institutional marine and maritime strategy is coming to citations. His area of specialisation is ecosystem goods fruition, which makes this an ideal time for us to host this triennial meeting. and services and ecological economics. Costanza’s Under the auspices of SANCOR, this is the second time we host SAMSS in PE and the transdisciplinary research integrates the study of theme ‘Embracing the blue – unlocking the ocean’s potential whilst maintaining social humans and nature to address research, policy, and and ecological resilience’ is highly topical and appropriate, aligning with Operation management issues. His work has focused on the Phakisa, which is the national approach to developing a blue economy. South Africa is interface between ecological and economic systems, at a cross roads and facing economic challenges. Economic growth and lifting people particularly at larger temporal and spatial scales, from out of poverty is a priority and those of us in the ‘marine’ community need to be part small watersheds to the global system. -

Sequencing Type Material Resolves the Identity and Distribution of the Generitype Lithophyllum Incrustans, and Related European Species L

J. Phycol. 51, 791–807 (2015) © 2015 Phycological Society of America DOI: 10.1111/jpy.12319 SEQUENCING TYPE MATERIAL RESOLVES THE IDENTITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE GENERITYPE LITHOPHYLLUM INCRUSTANS, AND RELATED EUROPEAN SPECIES L. HIBERNICUM AND L. BATHYPORUM (CORALLINALES, RHODOPHYTA)1 Jazmin J. Hernandez-Kantun2 Botany Department, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 166 PO Box 37012, Washington District of Columbia, USA Irish Seaweed Research Group, Ryan Institute, National University of Ireland, University Road, Galway Ireland Fabio Rindi Dipartimento di Scienze della Vita e dell’Ambiente, Universita Politecnica delle Marche, Via Brecce Bianche, Ancona 60131, Italy Walter H. Adey Botany Department, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 166 PO Box 37012, Washington District of Columbia, USA Svenja Heesch Irish Seaweed Research Group, Ryan Institute, National University of Ireland, University Road, Galway Ireland Viviana Pena~ BIOCOST Research Group, Departamento de Bioloxıa Animal, Bioloxıa Vexetal e Ecoloxıa, Facultade de Ciencias, Universidade da Coruna,~ Campus de A Coruna,~ A Coruna~ 15071, Spain Equipe Exploration, Especes et Evolution, Institut de Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 ISYEB CNRS, MNHN, UPMC, EPHE, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Sorbonne Universites, 57 rue Cuvier CP 39, Paris 75005, France Phycology Research Group, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281, Building S8, Ghent 9000, Belgium Line Le Gall Equipe Exploration, Especes et Evolution, Institut de Systematique, Evolution, Biodiversite, UMR 7205 ISYEB CNRS, MNHN, UPMC, EPHE, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Sorbonne Universites, 57 rue Cuvier CP 39, Paris 75005, France and Paul W. Gabrielson Department of Biology and Herbarium, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Coker Hall CB 3280, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-3280, USA DNA sequences from type material in the belonging in Lithophyllum. -

Taxonomic Novelties in the Fern Genus Tectaria (Tectariaceae)

Phytotaxa 122 (1): 61–64 (2013) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Article PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2013 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.122.1.3 Taxonomic novelties in the fern genus Tectaria (Tectariaceae) HUI-HUI DING1,2, YI-SHAN CHAO3 & SHI-YONG DONG1* 1 Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China. 2 Graduate University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China. 3 Division of Botanical Garden, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Taipei 10066, Taiwan. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The misapplication of the name Tectaria griffithii is corrected, which results in the revival of T. multicaudata and the proposal of a new combination (T. multicaudata var. amplissima) and two new synonyms (T. yunnanensis and T. multicaudata var. singaporeana). For the reduction of Psomiocarpa and Tectaridium (previously monotypic genera) into Tectaria, T. macleanii (new combination) and T. psomiocarpa (new name) are proposed as new combinations. In addition, the new name Tectaria subvariolosa is put forward to replace a later homonym (T. stenosemioides). Key words: nomenclature, Psomiocarpa, taxonomy, Tectaridium Introduction Tectaria Cavanilles (1799) (Tectariaceae) is a fern genus frequent in tropical regions, with most species growing terrestrially in rain forests. This group is remarkable for its extremely diverse morphology, and the estimated number of species ranges from 150 (Tryon & Tryon 1982; Kramer 1990) to 210 (Holttum 1991a). Holttum (1991a) recognized 105 species in Tectaria from Malesia and presumed that SE Asia is its center of origin. -

The Genus Phymatolithon (Hapalidiaceae, Corallinales, Rhodophyta) in South Africa, Including Species Previously Ascribed to Leptophytum

South African Journal of Botany 90 (2014) 170–192 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb The genus Phymatolithon (Hapalidiaceae, Corallinales, Rhodophyta) in South Africa, including species previously ascribed to Leptophytum E. Van der Merwe, G.W. Maneveldt ⁎ Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, University of the Western Cape, P. Bag X17, Bellville 7535, South Africa article info abstract Article history: Of the genera within the coralline algal subfamily Melobesioideae, the genera Leptophytum Adey and Received 2 May 2013 Phymatolithon Foslie have probably been the most contentious in recent years. In recent publications, the Received in revised form 4 November 2013 name Leptophytum was used in quotation marks because South African taxa ascribed to this genus had not Accepted 5 November 2013 been formally transferred to another genus or reduced to synonymy. The status and generic disposition of Available online 7 December 2013 those species (L. acervatum, L. ferox, L. foveatum) have remained unresolved ever since Düwel and Wegeberg Edited by JC Manning (1996) determined from a study of relevant types and other specimens that Leptophytum Adey was a heterotypic synonym of Phymatolithon Foslie. Based on our study of numerous recently collected specimens and of published Keywords: data on the relevant types, we have concluded that each of the above species previously ascribed to Leptophytum Non-geniculate coralline algae represents a distinct species of Phymatolithon, and that four species (incl. P. repandum)ofPhymatolithon are Phymatolithon acervatum currently known to occur in South Africa. Phymatolithon ferox Here we present detailed illustrated accounts of each of the four species, including: new data on male and female/ Phymatolithon foveatum carposporangial conceptacles; ecological and morphological/anatomical comparisons; and a review of the infor- Phymatolithon repandum mation on the various features used previously to separate Leptophytum and Phymatolithon. -

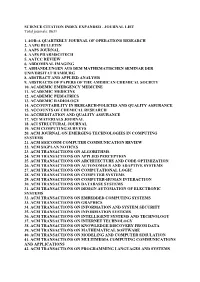

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Geologia Croaticacroatica

View metadata, citationGeologia and similar Croatica papers at core.ac.uk 61/2–3 333–340 1 Fig. 1 Pl. Zagreb 2008 333brought to you by CORE The coralline fl ora of a Miocene maërl: the Croatian “Litavac” Daniela Basso1, Davor Vrsaljko2 and Tonći Grgasović3 1 Dipartamento di Scienze Geologiche e Geotecnologie, Università degli Studi di Milano – Bicocca, Piazza della Scienza 4, 20126 Milano, Italy; ([email protected]) 2 Croatian Natural History Museum, Demetrova 1, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; ([email protected]) 3 Croatian Geological Survey, Sachsova 2, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia; ([email protected]) GeologiaGeologia CroaticaCroatica AB STRA CT The fossil coralline fl ora of the Badenian bioclastic limestone outcropping in Northern Croatia is known by the name “Litavac”, shortened from “Lithothamnium Limestone”. The name was given to indicate that unidentifi ed coralline algae are the major component. In this fi rst contribution to the knowledge of the coralline fl ora of the Litavac, Lithoth- amnion valens seems to be the most common species, with an unattached, branched growth-form. Small rhodoliths composed of Phymatolithon calcareum and Mesophyllum roveretoi also occur. The Badenian benthic association is dominated by melobesioid corallines, thus it can be compared with the modern maërl facies of the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Since L. valens still survives in the present-day Mediterranean, an analogy between the Badenian Litavac and the living L. valens facies of the Mediterranean is suggested. Keywor ds: calcareous Rhodophyta, Corallinales, rhodoliths, maërl, Badenian, Croatia 1. INTRODUCTION an overlying facies of fi ne-graded clastics: fi ne-graded sands, marls, clayey limestones and calcsiltites (VRSALJKO et al., Since Roman times, a building stone named “Litavac” has 2006, 2007a). -

The Role of Encrusting Coralline Algae in the Diets of Intertidal Herbivores

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of the Western Cape Research Repository Maneveldt, G.W. et al. (2006). The role of encrusting coralline algae in the diets of selected intertidal herbivores. JOURNAL OF APPLIED PHYCOLOGY, 18: 619-627 The role of encrusting coralline algae in the diets of selected intertidal herbivores Gavin W. Maneveldt*, Deborah Wilby, Michelle Potgieter & Martin G.J. Hendricks Department of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology University of the Western Cape P. Bag X17 Bellville 7535 South Africa * Correcsponding author: [email protected] Key words: encrusting coralline algae, diet, grazers, herbivory, organic content, rocky shore. Abstract Kalk Bay, South Africa, has a typical south coast zonation pattern with a band of seaweed dominating the mid-eulittoral and sandwiched between two molluscan- herbivore dominated upper and lower eulittoral zones. Encrusting coralline algae were very obvious features of these zones. The most abundant herbivores in the upper eulittoral were the limpet, Cymbula oculus (10.4 + 1.6 m-2; 201.65 + 32.68 g.m-2) and the false limpet, Siphonaria capensis (97.07 + 19.92 m-2; 77.93 + 16.02 g.m-2). The territorial gardening limpet, Scutellastra cochlear, dominated the lower eulittoral zone, achieving very high densities (545.27 + 84.35 m-2) and biomass (4630.17 + 556.13 g.m-2), and excluded all other herbivores and most seaweeds, except for its garden alga and the encrusting coralline alga, Spongities yendoi (35.93 + 2.26 % cover). For the upper eulittoral zone, only the chiton Acanthochiton garnoti 30.5 + 1.33 % and the limpet C. -

Corrections to Phytotaxa 19: Linear Sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns

Phytotaxa 28: 50–52 (2011) ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ Correction PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2011 Magnolia Press ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) Corrections to Phytotaxa 19: Linear sequence of lycophytes and ferns MAARTEN J.M. CHRISTENHUSZ1 & HARALD SCHNEIDER2 1Botany Unit, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Postbox 4, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Botany, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, SW7 5BD London, U.K. E-mail: [email protected] After the publication of our A linear sequence of extant families and genera of lycophytes and ferns (Christenhusz, Zhang & Schneider 2011), a couple of errors were brought to our attention: Platyzoma placed in Pteris (Pteridaceae), and correcting erroneous combinations made in Pteris of Gleichenia species. In the New Combinations section on page 22, we attempted to provide new combinations for the genus Platyzoma R.Br., which is embedded in Pteris L. (Schuettpelz & Pryer 2007, Lehtonen 2011). When doing so, we made the unfortunate choice to follow the treatment of Platyzoma by Desvaux (1827), which included several additional species of Gleichenia, instead of the modern treatment of Platyzoma in which only the species Platyzoma microphyllum Brown (1810: 160) is included. Only that name needed to be transferred. This resulted in the creation of a number of unnecessary new names and combinations of Australasian Gleichenia, for which we apologise. We erroneously provided names in Pteris for Gleichenia dicarpa R.Br., G. alpina R.Br. and G. rupestris R.Br., which are all correctly placed in Gleichenia and not in Pteris. Therefore these new names are to be treated as synonyms. -

Hierarchical Spatial Structure and Levels of Resolution of Intertidal Grazing and Their Consequences on Predictability and Stability at Small Scales

Hierarchical spatial structure and levels of resolution of intertidal grazing and their consequences on predictability and stability at small scales Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of Rhodes University By ELIECER RODRIGO DIAZ DIAZ June 2008 Abstract The aim of this research was to assess three hierarchical aspects of alga-grazer interactions in intertidal communities on a small scale: spatial heterogeneity, grazing effects and spatial stability in grazing effects. First, using semivariograms and cross-semivariograms I observed hierarchical spatial patterns in most algal groups and in grazers. However, these patterns varied with the level on the shore and between shores, suggesting that either human exploitation or wave exposure can be a source of variability. Second, grazing effects were studied using manipulative experiments at different levels on the shore. These revealed significant effects of grazing on the low shore and in tidal pools. Additionally, using a transect of grazer exclusions across the shore, I observed unexpected hierarchical patchiness in the strength of grazing, rather than zonation in its effects. This patchiness varied in time due to different biotic and abiotic factors. In a separate experiment, the effect of mesograzers effects were studied in the upper eulittoral zone under four conditions: burnt open rock (BOR), burnt pools (Bpool), non- burnt open rock (NBOR) and non-burnt pools (NBpool). Additionally, I tested spatial stability in the effects of grazing in consecutive years, using the same plots. I observed great spatial variability in the effects of grazing, but this variability was spatially stable in Bpools and NBOR, meaning deterministic and significant grazing effects in consecutive years on the same plots. -

It Was Recognized During Geological Excursions in the Bükk Mountains

NEWER LIME-SECRETING ALGAE FROM THE MIDDLE CARBONIFEROUS OF THE BÜKK MOUNTAINS, NORTHERN HUNGARY M. NEMETH INTRODUCTION It was recognized during geological excursions in the Bükk Mountains that certain limestone lenses of the Upper Moscovian shale sequence yield other calcareous algae than those dasycladaceans (Vermiporella sp., Anthracoporella sp., A. spectabilis PIA and Dvinella comata CHVOROVA) described previously by HERAK, M. and Ko- CHANSKY, V. [1963]. From limestone samples came from the No. 1 railway cutting of Nagyvisnyó, from the eastern side of the Bánvölgy (NW to the Dédes Castle), from the southern vicinity of the village Mályinka, from Kapubérc, from western side of the summit of Tarófő and from deeper part of the main lens of Nagyberenás the forms of the genera Archaeolithophyllum, Ivanovia, Oligoporellal and Osagia have been recognized. The first two genera belong into the phylloid algae of PRAY, L, C. and WRAY, J. L. [1963]. The genus Macroporella is classed among the family Dasydadaceae, while the Osagia is a crustose calcareous alga of uncertain systemat- ic position. Most interesting are the phylloid algae, which are similar in shape and size to leaves and are slightly or strongerly wavy, in spite of the morphological similarity that suggested by their common name, these are forms of different groups (e.g. green or red algae). This group was named by American authors, because these phylloid algae are abundant, occasionally in rock-forming quantity in the Middle and Upper Carboniferous (Pennsylvanián) and Lower Permian of the USA. On the other hand, the preservation of the cavities between the wavy plates of these algae pro- motes significantly the formation of hydrocarbon traps within the embedding rocks.