The Dog of Pompeii by Louis Untermeyer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand Grade 3

Grade 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Skills Strand Ancient Rome Ancient Stories of of Stories Unit 4 Reader 4 Unit Stories of Ancient Rome Unit 4 Reader Skills Strand GraDE 3 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again! are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

Continuity of Culture: Romans in Pompeii Lesson Overview

Continuity of Culture: Romans in Pompeii Lesson Overview Unit: Lessons: 1. Grades 3 – 6 Continuity of Culture: Lesson One: Map study of 2. 5 -7 Class Periods Romans in Pompeii Italy. 3. Authors: Lori Howell, Lesson Two: History of Melody Nishinaga, Sarah Pompeii. Poku & Warren Soper Lesson Three: Pliny the 4. Social Sciences, Younger. English and History Lesson Four: Comparison of “Then and Now.” Lesson Five: Literature review. Lesson Six: Graphic Organizes. Lesson Seven: Writing Overview “A typical day in this town means going shopping, stopping by the laundry, catching a sporting event at the amphitheater, or maybe taking in a play – and that was 2000 years ago. “Can you guess where this is? Not where you might expect: You’re in ancient Pompeii, an Italian village where life came to a fiery halt when Mt. Vesuvius erupted in AD 79. “ -Discover Kids Pompeii Magazine 1 | Page The eruption of Vesuvius on August 24, 79 A.D. froze a moment in time under thick layers of ash and molten mud. It preserved elements of Roman culture that demonstrate the remarkable continuity of human life and history, proving that life in the past, even the far distant past, was remarkably similar to our own. In this lesson, by taking a closer look at the remains of Pompeii, students will gain a broad appreciation of people in the past. They will study Roman culture by locating Pompeii on a map, identifying important elements of its geography, and examining the remains of Pompeii to explain how the Ancient Romans in Pompeii are similar to people today. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Robert Harris • Enigma

LITERARY BITS Module 2 WORKING IN DIGITAL ROBERT HARRIS • ENIGMA ABOUT THE AUTHOR ROBERT HARRIS Robert Harris was born in Nottingham, UK, in 1957. After graduating at Cambridge, he worked as a journalist for the BBC and assisted on shows that covered important current events. He became a political commentator, was the editor of The Observer, a UK political paper, and wrote articles on politics in many other newspapers. He started his writing career in the 1980s and since then he has written a number of fictional thrillers, often related to political events, and eight novels have become bestsellers. He wrote novels related to World War Two such as ‘Fatherland’ (1992), his first bestseller, and ‘Enigma’ (1995), but also stories set in other historical periods like ‘Pompeii’ (2003). R. Harris ABOUT THE NOVEL ENIGMA The novel is a blend between a historical novel and a mystery novel which mixes up reality and fiction. The story is set in 1943 when much of Nazi Enigma Code has already been cracked. However, Shark, the impenetrable cipher used to hide the movements of the U-boats, the German submarines, to the Allies, is still a mystery. A top secret team of British cryptographers led by the brilliant mathematician Tom Jericho has the task of deciphering it. They succeed in breaking the code, but unfortunately the Germans change it. As an Allied convoy crosses the North Atlantic Ocean full of U-boats, Jericho has to solve three mysteries with the help of his girlfriend’s roommate who is on the convoy: the code, whether his girlfriend Claire is a spy and if she has been murdered. -

The JB's These Are the JB's Mp3, Flac

The J.B.'s These Are The J.B.'s mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: These Are The J.B.'s Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Funk MP3 version RAR size: 1439 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1960 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 880 Other Formats: APE VOX AC3 AA ASF MIDI VQF Tracklist Hide Credits These Are the JB's, Pts. 1 & 2 1 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 4:45 Frank Clifford Waddy*, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins 2 I’ll Ze 10:38 The Grunt, Pts. 1 & 2 Written-By – Phelps Collins*, Clayton Isiah Gunnels*, Clyde Stubblefield, Darrell Jamison*, 3 3:29 Frank Clifford Waddy*, James Brown, John W. Griggs*, Robert McCollough*, William Earl Collins Medley: When You Feel It Grunt If You Can 4 Written-By – Art Neville, Gene Redd*, George Porter Jr.*, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, 12:57 Joseph Modeliste, Kool & The Gang, Leo Nocentelli Companies, etc. Recorded At – King Studios Recorded At – Starday Studios Phonographic Copyright (p) – Universal Records Copyright (c) – Universal Records Manufactured By – Universal Music Enterprises Credits Bass – William "Bootsy" Collins* Congas – Johnny Griggs Drums – Clyde Stubblefield (tracks: 1, 4 (the latter probably)), Frank "Kash" Waddy* (tracks: 2, 3, 4) Engineer [Original Sessions] – Ron Lenhoff Engineer [Restoration], Remastered By – Dave Cooley Flute, Baritone Saxophone – St. Clair Pinckney* (tracks: 1) Guitar – Phelps "Catfish" Collins* Organ – James Brown (tracks: 2) Piano – Bobby Byrd (tracks: 3) Producer [Original Sessions] – James Brown Reissue Producer – Eothen Alapatt Tenor Saxophone – Robert McCullough* Trumpet – Clayton "Chicken" Gunnels*, Darryl "Hasaan" Jamison* Notes Originally scheduled for release in July 1971 as King SLP 1126. -

1 Classics 270 Economic Life of Pompeii

CLASSICS 270 ECONOMIC LIFE OF POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM FALL, 2014 SOME USEFUL PUBLICATIONS Annuals: Cronache Pompeiane (1975-1979; volumes 1-5) (Gardner: volumes 1-5 DG70.P7 C7) Rivista di Studi Pompeiani (1987-present; volumes 1-23 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-3 DG70.P7 R585; CTP vols. 6-23 DG70.P7 R58) Cronache Ercolanesi: (1971-present; volumes 1-43 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1-19 PA3317 .C7) Vesuviana: An International Journal of Archaeological and Historical Studies on Pompeii and Herculaneum (2009 volume 1; others late) (Gardner: DG70.P7 V47 2009 V. 1) Notizie degli Scavi dell’Antichità (Gardner: beginning 1903, mostly in NRLF; viewable on line back to 1876 at: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000503523) Series: Quaderni di Studi Pompeiani (2007-present; volumes 1-6 [2013]) (Gardner: volumes 1, 5) Studi della Soprintendenza archeologica di Pompei (2001-present; volumes 1-32 [2012]) (Gardner: volumes 1-32 (2012)] Bibliography: García y García, Laurentino. 1998. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei Monografie 14, 2 vol. (Rome). García y García, Laurentino. 2012. Nova Bibliotheca Pompeiana. Supplemento 1o (1999-2011) (Rome: Arbor Sapientiae). McIlwaine, I. 1988. Herculaneum: A guide to Printed Sources. (Naples: Bibliopolis). McIlwaine, I. 2009. Herculaneum: A guide to Sources, 1980-2007. (Naples: Bibliopolis). 1 Early documentation: Fiorelli, G. 1861-1865. Giornale degli scavi. 31 vols. Hathi Trust Digital Library: http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009049482 Fiorelli, G. ed. 1860-1864. Pompeianarum antiquitatum historia. 3 vols. (Naples: Editore Prid. Non. Martias). Laidlaw, A. 2007. “Mining the early published sources: problems and pitfalls.” In Dobbins and Foss eds. pp. 620-636. Epigraphy: Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 4 (instrumentum domesticum from Vesuvian sites), 10 (inscriptions from various regions, including Campania). -

INDIVIDUATION and MYSTICAL UNION Jung and Eckhart

MARK JAMES INDIVIDUATION AND MYSTICAL UNION Jung and Eckhart Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) regularly quoted Meister Eckhart (ca.1260-1328) approvingly in his writings on Christianity.1 Jung thought that Christianity was suffering from arrested development and saw in Eckhart an ally. For Jung Chris- tianity and Christian symbols were in danger of being eclipsed because they no longer spoke to the human condition in the twentieth century. Churches that were supposed to care for the salvation of the soul were no longer able to help the individual achieve metanoia, the rebirth of the spirit. The Christian faith had lost its ability to connect people with an experience of the inner presence of God in their lives. Christianity, he believed, proclaimed an externalised God, a God aloof from people’s experience. While this externalisation of religion united individuals into a community of believers and even empowered them to provide a valuable social service to society, it lacked the capacity to transform the person’s inner life.2 It reinforces the idea that everything originates from without the person. A new process of self-nourishment was required which feeds a person’s interior life from internal not external resources. This means that Christianity could no longer remain a creed or a dogma of beliefs to which people adhered. In Eckhart, Jung saw a man after his own heart who sought to proclaim an immanent God and move away from the conception of God as ‘wholly other’.3 This comparative study seeks to contribute towards the ongoing discussion regarding the relationship between psychology and mysticism in spirituality stud- ies by engaging Jung and Eckhart in a dialogue with each other. -

OVID Dipsas the Sorceress

Eduqas GCSE Latin Component 2: Latin Literature and Sources (Themes) Superstition and Magic OVID Dipsas the sorceress Teachers should not feel that they need to pass on to their students all the information from these notes; they should choose whatever they think is appropriate. The examination requires knowledge outside the text only when it is needed in order to understand the text. The Teacher’s Notes contain the following: • An Introduction to the author and the text, although students will only be asked questions on the content of the source itself. • Notes on the text to assist the teacher. • Suggested Questions for Comprehension, Content and Style to be used with students. • Discussion suggestions and questions for students, and overarching Themes which appear across more than one source. • Further Information and Reading for teachers who wish to explore the topic and texts further. © University of Cambridge School Classics Project, 2019 PUBLISHED BY THE CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL CLASSICS PROJECT Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, 184 Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 8PQ, UK http://www.CambridgeSCP.com © University of Cambridge School Classics Project, 2019 Copyright In the case of this publication, the CSCP is waiving normal copyright provisions in that copies of this material may be made free of charge and without specific permission so long as they are for educational or personal use within the school or institution which downloads the publication. All other forms of copying (for example, for inclusion in another publication) are subject to specific permission from the Project. First published 2019 version date: 20/12/2019 This document refers to the official examination images and texts for the Eduqas Latin GCSE (2021 - 2023). -

The Legacy of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages in the West The

The Legacy of the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages in the West The Roman Empire reigned from 27 BCE to 476 CE throughout the Mediterranean world, including parts of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. The fall of the Roman Empire in the West in 476 CE marked the end of the period of classical antiquity and ushered in a new era in world history. Three civilizations emerged as successors to the Romans in the Mediterranean world: the Byzantine Empire (in many ways a continuation of the Eastern Roman Empire), and the civilizations of Islam and Western Europe. These three civilizations would become rivals and adversaries over the course of the succeeding centuries. They developed distinct religious, cultural, social, political, and linguistic characteristics that shaped the path each civilization would take throughout the course of the Middle Ages and beyond. The Middle Ages in European history refers to the period spanning the fifth through the fifteenth century. The fall of the Western Roman Empire typically represents the beginning of the Middle Ages. Scholars divide the Middle Ages into three eras: the Early Middle Ages (400–1000), the High Middle Ages (1000–1300), and the Late Middle Ages (1300–1500). The Renaissance and the Age of Discovery traditionally mark the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the early modern period in European history. The legacy of the Roman Empire, and the division of its territory into three separate civilizations, impacted the course of world history and continues to influence the development of each region to this day. -

Classics, Greek, Latin

CLASSICS, GREEK, LATIN FALL 2021 COURSE OFFERINGS CL 250 Classical Drama in English MWF 12:00-12:50 pm (Core: CAPA) CL 301 Topics in Ancient Greek History T/Th 3:30-4:45 pm (Core: HUM) GK 101 Beginning Ancient Greek I MWF 1:00-1:50 pm LT 101 Beginning Latin I MWF 9:00-9:50 am LT 201 Intermediate Latin I M/F 2:00-3:15 pm (Core: Catholic Studies) LT 370 Latin Literature of Late Antiquity T/Th 12:30-1:45 pm (Core: HUM, Catholic Studies) CLASSICS PROFESSOR: G. COMPTON-ENGLE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR: K.A. EHRHARDT MAJORS ▬ Classical Languages Classical Studies MAJOR REQUIREMENTS ▬ (As of 2021-22 Bulletin) MINOR ▬ Classical Languages: 36 Credit Hours Classical Studies Eight 3-credit courses in Greek and/or ▬ Latin at any level WHY STUDY CLASSICS Classics 301 or 302 The study of Greek and Roman Classics 410 Capstone cultures provides students with a And two Classics electives better understanding of their own culture, which has been strongly Classical Studies: 36 Credit Hours influenced by Roman and Greek art, Four 3-credit courses in Greek and/or medicine, law and religion. Latin, including at least one 300-level An education in Classics prepares course students for a variety of careers CL 220, 250, or 330, or another including law, teaching, diplomatic approved literature course service, library sciences, medicine, Two of the following: CL 301, CL 302, and business. HS 205, HS 305, or another approved CL or HS course MINOR REQUIREMENTS ▬ Two of the following: PL 210, TRS 200, Classical Studies: 18 Credit Hours TRS 205, TRS 301, TRS 316, TRS 329, or another approved PL or TRS course Six courses in any combination of Six credits of electives in CL, GK, LT or Greek, Latin, Classics, PL 210, TRS 205, other approved course on the ancient HS 205, HS 305, or other approved world. -

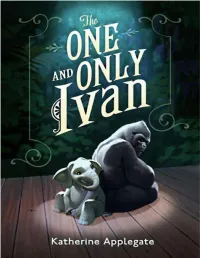

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

The Birth-Mark Hawthorne, Nathaniel

The Birth-Mark Hawthorne, Nathaniel Published: 1843 Type(s): Short Fiction Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Hawthorne: Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachu- setts, where his birthplace is now a museum. William Hathorne, who emigrated from England in 1630, was the first of Hawthorne's ancestors to arrive in the colonies. After arriving, William persecuted Quakers. William's son John Hathorne was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem Witch Trials. (One theory is that having learned about this, the au- thor added the "w" to his surname in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college.) Hawthorne's father, Nathaniel Hathorne, Sr., was a sea captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever, when Hawthorne was only four years old, in Raymond, Maine. Hawthorne attended Bowdoin College at the expense of an uncle from 1821 to 1824, befriending classmates Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and future president Franklin Pierce. While there he joined the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity. Until the publication of his Twice-Told Tales in 1837, Hawthorne wrote in the comparative obscurity of what he called his "owl's nest" in the family home. As he looked back on this period of his life, he wrote: "I have not lived, but only dreamed about living." And yet it was this period of brooding and writing that had formed, as Malcolm Cowley was to describe it, "the central fact in Hawthorne's career," his "term of apprenticeship" that would eventually result in the "richly med- itated fiction." Hawthorne was hired in 1839 as a weigher and gauger at the Boston Custom House.