Federal Bureau of Prisons' Monitoring of Mail for High-Risk Inmates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

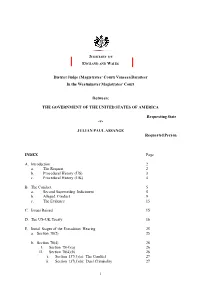

USA -V- Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

The Open Door How Militant Islamic Terrorists Entered and Remained in the United States, 1993-2001 by Steven A

Center for Immigration Studies The Open Door How Militant Islamic Terrorists Entered and Remained in the United States, 1993-2001 By Steven A. Camarota Center for Immigration Studies Center for 1 Center Paper 21 Center for Immigration Studies About the Author Steven A. Camarota is Director of Research at the Center for Immigration Studies in Wash- ington, D.C. He holds a master’s degree in political science from the University of Pennsyl- vania and a Ph.D. in public policy analysis from the University of Virginia. Dr. Camarota has testified before Congress and has published widely on the political and economic ef- fects of immigration on the United States. His articles on the impact of immigration have appeared in both academic publications and the popular press including Social Science Quarterly, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, Campaigns and Elections, and National Review. His most recent works published by the Center for Immigration Studies are: The New Ellis Islands: Examining Non-Traditional Areas of Immigrant Settlement in the 1990s, Immigration from Mexico: Assessing the Impact on the United States, The Slowing Progress of Immigrants: An Examination of Income, Home Ownership, and Citizenship, 1970-2000, Without Coverage: Immigration’s Impact on the Size and Growth of the Population Lacking Health Insurance, and Reconsidering Immigrant Entrepreneurship: An Examination of Self- Employment Among Natives and the Foreign-born. About the Center The Center for Immigration Studies, founded in 1985, is a non-profit, non-partisan re- search organization in Washington, D.C., that examines and critiques the impact of immi- gration on the United States. -

Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4732

S4732 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE April 27, 2009 lights to go on when we flip a switch, and we plant was being closed, more than 130 ‘‘Hopefully, when we obtain the power con- do not expect our computers to shut down as ALCOA employees accepted the company’s tract, it will just be a matter of waiting for nature dictates. severance package. Others were laid off—245 the market to pick up again. The good thing Solar and wind electricity are available hourly workers and 80 of the salaried work- about aluminum is that it is used in more only part of the time that consumers de- force. and more applications. It’s going to be mand power. Solar cells produce no electric The London Metal Exchange price for alu- around for a long time.’’ power at night, and clouds greatly reduce minum is half what it was one year ago, so their output. The wind doesn’t blow at a con- prospects for any immediate change is nil. f stant rate, and sometimes it does not blow The demand for the 1.3 million pounds of GUANTANAMO BAY at all. molten metal that the smelting plant can If large-scale electric energy storage were produce does not exist in the current mar- Mr. JOHANNS. Mr. President, I rise viable, solar and wind intermittency would ketplace. to speak about the detainment facili- be less of a problem. However, large-scale Still, leadership at the company is hopeful ties at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. electric energy storage is possible only in that when the economy rebounds, Tennessee At the end of January of this year, the few locations where there are hydro- Smelting Operations will be in a position to be restarted. -

PAYING the PRICE for SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

PAYING the PRICE for SOLITARY CONFINEMENT Over the past few decades, United States corrections How Much More Does It Cost? systems have increasingly relied on the use of solitary The high costs of solitary confinement have been confinement as a tool to manage certain incarcerated documented by many states as well as the federal populations. Prisoners in solitary confinement remain government. Below are some examples: alone in their cells for 22-24 hours per day – for months, years, and even decades at a time. This practice, which States: has been shown to be inhumane and ineffective, is also • Arizona: A 2007 estimate from Arizona put the extremely costly. Though limited nationwide data exists, annual cost of holding a prisoner in solitary state data suggests that the cost of housing a prisoner in confinement at approximately $50,000, compared solitary confinement is 2-3 times that of housing a to about $20,000 for the average prisoner.5 1 prisoner in general population. • California: For 2010-2011, inmates in isolation at Pelican Bay State Prison’s Administrative Why is Solitary More Expensive? Segregation Unit cost $77,740 annually, while inmates in general population cost $58,324.6 Holding prisoners in solitary confinement is resource- Statewide, taxpayers pay an additional $175 intensive from start to finish. Below are two of the biggest million annually to keep prisoners in solitary costs associated with the use of solitary confinement. confinement.7 Construction: To accommodate the vast numbers of • Connecticut: In Connecticut, housing a prisoner in prisoners kept in solitary confinement, a new kind of solitary confinement costs an average of twice as prison has emerged. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:12-cv-01872-RC Document 259 Filed 01/04/16 Page 1 of 64 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA JEREMY PINSON : : Plaintiff, : : Civil Action No.: 12-1872 (RC) v. : : Re Document No.: 147 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, et al., : : Defendants. : MEMORANDUM OPINION GRANTING IN PART AND DENYING IN PART DEFENDANTS’ MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT I. INTRODUCTION Pro se Plaintiff Jeremy Pinson is currently an inmate at ADX Florence, a federal prison located in Colorado. While in prison, Mr. Pinson has filed multiple Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”), 5 U.S.C. § 552, requests with different components of the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”). On several occasions, the DOJ has asked Mr. Pinson to clarify his records requests, told him that it could not find records that are responsive to his requests, or informed him that the records he sought were exempt from disclosure by law. Mr. Pinson took issue with some of these determinations, so he filed a complaint claiming that the DOJ improperly withheld numerous records from him in violation of FOIA. In response, the DOJ filed several pre-answer motions, each asking the Court to dismiss or grant summary judgment in its favor on different portions of Mr. Pinson’s complaint. Now before the Court is the DOJ’s motion for summary judgment as to Mr. Pinson’s numerous FOIA requests submitted to the Federal Bureau of Prisons (“BOP”) and several claims Case 1:12-cv-01872-RC Document 259 Filed 01/04/16 Page 2 of 64 brought against BOP employees pursuant to Bivens v. -

The World Trade Center Bombers ( 1993) John V

Chapter 11 The World Trade Center Bombers ( 1993) John V. Parachini The February 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City marked the beginning of an ugly new phase of terrorism involving the indiscriminate killing of civilians. ’ Like the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway in March 1995 and the bombing of the Alfred E. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in April 4995, the World Trade Center bomb- ing was motivated by the desire to kill as many people as possible. The target of the bomb plot was the World Trade Center (WTC) complex, a sixteen-acre site in lower Manhattan. Although mostly known for the Twin Towers, which are 110 stories tall and 1,550 feet high, the complex consists of seven buildings, including the Vista Hotel. Although the explosion killed six people and injured more than 1,000, the conse- quences could have been far worse: on any given day approximately 20,000 people work in the various businesses of the WTC complex and another 80,000 people either visit the complex or travel through it.2 On May 24,1994, during the sentencing of four of the convicted WTC bombers, Judge Kevin T. Duffy asserted that the perpetrators had incor- porated sodium cyanide into the bomb with the intent to generate deadly hydrogen cyanide gas that would kill everyone in one of the towers. The Judge stated: 1. Jim Dwyer, David Kocieniewski, Deidre Murphy, and Peg Tyre, Two Seconds Under the World: Terror Comes fo America-Ike Conspiracy Behind the World Trade Center Bombing (New York: Crown Publishers, 1994), p. -

United States V. Ramzi Ahmed Yousef

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT August Term, 2001 (Argued: May 3, 2002 Decided: April 4, 2003 Errata Filed: April 14, 2003 Errata Filed: June 18, 2003) Docket Nos. 98-1041 L 98-1197 98-1355 99-1544 99-1554 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. RAMZI AHMED YOUSEF,EYAD ISMOIL, also known as EYAD ISMAIL, and ABDUL HAKIM MURAD, also known as SAEED AHMED, Defendants-Appellants, MOHAMMED A. SALAMEH,NIDAL AYYAD,MAHMUD ABOUHALIMA, also known as Mahmoud Abu Halima, BILAL ALKAISI, also known as Bilal Elqisi, AHMAD MOHAMMAD AJAJ, also know as Khurram Khan, ABDUL RAHMAN YASIN, also know as Aboud, and WALI KHAN AMIN SHAH, also known as Grabi Ibrahim Hahsen, Defendants. Before: WALKER, Chief Judge,WINTER,CABRANES, Circuit Judges. Appeal by Ramzi Yousef, Eyad Ismoil, and Abdul Hakim Murad from judgments of conviction entered in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Kevin Thomas Duffy, Judge) on April 13, June 2, and June 15, 1998, respectively. Judge Duffy presided over two separate jury trials. In the first trial, Yousef, Murad, and another defendant were tried on charges relating to a conspiracy to bomb twelve United States commercial airliners in Southeast Asia. In the second trial, Yousef and Ismoil were tried for their involvement in the February 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York City. Yousef, Ismoil, and Murad now appeal from their convictions, raising numerous questions of domestic and international law. Yousef and Ismoil also appeal from the District Court’s denial of several of their post-judgment motions. -

United States' Compliance with the International

________________________________________________________________________ United States’ Compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights American Civil Liberties Union Update to the Shadow Report to the Fourth Periodic Report of the United States 110th Session of the Human Rights Committee, Geneva 10-28 March 2014 ________________________________________________________________________ 14 February 2014 American Civil Liberties Union 125 Broad St, 17th Floor New York, NY 10004 P: 212 549 2500 [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………2 Updates to Shadow Report from September 2013 Anti-Immigrant Measures at the State and Federal Levels...……………………………..3 U.S.-Mexico Border Killings and Militarization of the Border…………………………..4 Solitary Confinement……………………………………………………………………..8 The Death Penalty……………………………………………………………………….10 Accountability for Torture and Abuse during the Bush Administration………………...12 Targeted Killings………………………………………………………………………...14 NSA Surveillance Programs……………………………………………………………..16 Annex: ACLU Shadow Report from September 2013 Acknowledgments ACLU staff from the following projects, departments, and affiliates researched, wrote, reviewed, and/or edited sections of the ACLU shadow report and the following update: Human Rights Program, Immigrants’ Rights Project, Capital Punishment Project, National Prison Project, National Security Project, Women’s Rights Project, Affiliate Support and Advocacy, Washington Legislative Office, ACLU of New Mexico Regional Center for Border Rights, ACLU of Arizona, and ACLU of San Diego & Imperial Counties. 1 Introduction This submission updates the report of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) submitted to the U.N. Human Rights Committee (“the Committee”) in September 2013. This update reflects the most significant developments since our report was submitted. The United States review before the Committee was rescheduled to March 13 and 14, 2014 due to the U.S. -

Judgment Lord Justice Scott Baker

Neutral Citation Number: [2009] EWHC 2068 (Admin) Case No: CO/5577/2008 and C0/5511/2008 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION DIVISIONAL COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 07/08/2009 Before : LORD JUSTICE SCOTT BAKER - and - MR JUSTICE DAVID CLARKE - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between: THE QUEEN (ON THE APPLICATION OF Claimants ADEL ABDUL BARY AND KHALID AL FAWWAZ) - and - THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE Defendant HOME DEPARTMENT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Richard Drabble Q.C and Ben Cooper (instructed by Birnberg Pierce and Partners) for Bary Edward Fitzgerald Q.C. and John Jones ( instructed by Quist Solicitors ) for Al Fawwaz David Perry Q.C and Adam Robb ( instructed by the Treasury Solicitor) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 12, 13 February and 20 July 2009 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Lord Justice Scott Baker: Introduction 1. The two claimants, Adel Abdul Bary and Khalid Al Fawwaz, are accused by the Government of the United States of America of participation in a conspiracy to murder United States citizens, United States diplomats and other internationally protected persons. It is alleged that a key figure in the conspiracy was Osama Bin Laden and that two of the overt acts of the conspiracy were the synchronised bombings of the United States embassies in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam on 7 August 1998. As a result of the explosion in Nairobi 213 people died and some 4,500 were injured. 11 people died as a result of the Dar Es Salaam explosion. 2. Following an investigation into the bombings, the United States government sought the extradition of the two claimants and a third man, Eiderous. -

Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research and Prevention

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research and Prevention Author(s): Mark S. Hamm Document No.: 211203 Date Received: September 2005 Award Number: 2003-DT-CX-0002 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Crimes Committed by Terrorist Groups: Theory, Research, and Prevention Award #2003 DT CX 0002 Mark S. Hamm Criminology Department Indiana State University Terre Haute, IN 47809 Final Final Report Submitted: June 1, 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 2003-DT-CX-0002 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................. iv Executive Summary.................................................... -

Immigration and Terrorism: Moving Beyond the 9/11 Staff Report on Terrorist Travel Janice L

Immigration and Terrorism: Moving Beyond the 9/11 Staff Report on Terrorist Travel Janice L. Kephart ∗ OH GOD, you who open all doors, please open all doors for me, open all venues for me, open all avenues for me. – Mohammed Atta Introduction In August 2004, on the last day the 9/11 Commission was statutorily permitted to exist, a 240-page staff report describing the 9/11 Commission border team’s fifteen months of work in the area of immigration, visas, and border control was published on the 1 web. Our report, 9/11 and Terrorist Travel, focused on answering the question of how the hijackers of September 11 managed to enter and stay in the United States.2 To do so, we looked closely at the immigration records of the individual hijackers, along with larger policy questions of how and why our border security agencies failed us. The goal of this essay is to build on that report in two areas: • To provide additional facts about the immigration tactics of indicted and con- victed operatives of Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and other terrorist groups from the 1990s through the end of 2004. • To enlarge the policy discussion regarding the relationship between national security and immigration control. This report does not necessarily reflect the views of the 9/11 Commission or its staff. ∗ Janice Kephart is former counsel to the September 11 Commission. She has testified before the U.S. Congress, and has made numerous appearances in print and broadcast media. Re- search used in preparing portions of this report was conducted with the assistance of (former) select staff of the Investigative Project on Terrorism, Josh Lefkowitz, Jacob Wallace, and Jeremiah Baronberg.