Technical Writing in the English Renaissance 1475-1640

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experiences with Technical Writing Pedagogy Within a Mechanical Engineering Curriculum

Session 1141 Learning To Write: Experiences with Technical Writing Pedagogy Within a Mechanical Engineering Curriculum Beth Daniell1, Richard Figliola2, David Moline2, and Art Young1 1Department of English 2Department of Mechanical Engineering Clemson University, Clemson, SC 29631 Abstract This case study draws from a recent experience in which we critically reviewed our efforts of teaching technical writing within our undergraduate laboratories. We address the questions: “What do we want to accomplish?” and “So how might we do this effectively and efficiently?” As part of Clemson University's Writing-Across-The-Curriculum Program, English department consultants worked with Mechanical Engineering faculty and graduate assistants on technical writing pedagogy. We report on audience, genre, and conventions as important issues in lab reports and have recommended specific strategies across the program for improvements. Introduction Pedagogical questions continue about the content, feedback and methodology of the technical laboratory writing experience in engineering programs. In fact, there is no known prescription for success, and different programs try different approaches. Some programs delegate primary technical writing instruction to campus English departments, while others maintain such instruction within the engineering department, and hybrids in-between exist. But the approaches seem as much driven by financial necessity and numbers efficiency as they are by pedagogical effectiveness. While better-heeled departments can employ technically trained writing specialists to tutor students individually, the overwhelming majority of engineers are trained at quality institutions whose available resources require other methods. So how can we do this effectively and efficiently? At the heart of the matter is the question, “What do we want to accomplish?” We find ourselves trying to accomplish two instructional tasks that are often competing and we suspect that we are not alone. -

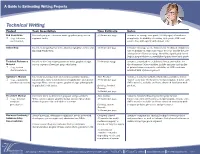

Technical Writing

A Guide to Estimating Writing Projects Technical Writing Project Task Description Time Estimate Notes End User Guide Research, prepare, interview, write, graphics prep, screen 3-5 hours per page Assumes an average user guide (20-80 pages) of moderate r (e.g., software captures, index. complexity. Availability of existing style guide, SME’s and user manual) source docs will significantly impact time. Online Help Interview, design/layout, write, illustrate/graphics, revise and 3-6 hours per page Consider one page as one help screen. Technical complexity final link verification. and availability of SME’s and source docs are usually the gov- erning factors. Hours per page should be significantly less if help is prepared from an established paper-based user guide. Technical Reference Interview developers/programmers, write, graphic design, 5-9 hours per page Assumes a standard or established format and outline for Material screen captures, flowchart prep, edit, index. the document. Other variables include quantity and quality r (e.g., system of printed source materials, availability of SME’s and time documentation) involved with system or project. Operator’s Manual Interview users/operators to determine product purpose, New Product: Assumes standard/established boilerplate/template format r (e.g., equipment/ functionality, safety considerations, (if applicable) and operat- 3-5 hours per page - factor extra time (10 hours) to design template if none exist. product operation) ing steps. Write, screen capture, graphic design, (photographs, SME’s must be available and have advanced familiarity with if applicable), edit, index. Existing Product product. Rewrite: 1-4 hours per page Procedure Manual Interview users to determine purpose and procedures. -

Healthcare Technical Writer for Interactive Software

Healthcare Technical Writer for Interactive Software ABOUT US We are looking for an outstanding Medical/Technical writer to create highly engaging, interactive health applications. If you are looking to make your mark in a small but a fast-moving health technology company with a position that has autonomy and variety, you could really shine here. For most of our 15 years, Medicom Health Interactive created award-winning educational/marketing software tools for healthcare clients like Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, GSK, the NCI, the ADA, and the AHA. Several years ago, we pivoted the company to focus exclusively on our patient engagement products. These products help top-tier healthcare systems with outreach/awareness to new patients. Visit www.medicomhealth.com for more detail. In 3 of the last 4 years, we have earned Minnesota Business Magazine’s “100 Best Companies To Work For” award, and have previously been named to the Minneapolis/St. Paul Business Journal’s “Fast 50” list of Minnesota’s fastest growing companies. Many of our staff have been here 5, 10, and 15 years. We have recently completed our first capital raise and are poised for additional growth. We pride ourselves on the quality of our work, adaptability, independence, cooperation, and a diverse mix of analytical and creative skills. We are seeking candidates who share these values. POSITION OVERVIEW The Healthcare Technical Writer documents the content and logic (no coding or graphic design) for our new and existing health/wellness web applications. This position is responsible for creating and maintaining the content and documentation of our interactive products in collaboration with our UI/UX specialists and Software Applications Developers. -

Technical Documentation Style Guide

KSC-DF-107 Revision F TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION STYLE GUIDE July 8, 2017 Engineering Directorate National Aeronautics and Space Administration John F. Kennedy Space Center KSC FORM 16-12 06/95 (1.0) PREVIOUS EDITIONS MAY BE USED KDP-T-5411_Rev_Basic-1 APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE — DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED KSC-DF-107 Revision F RECORD OF REVISIONS/CHANGES REV CHG LTR NO. DESCRIPTION DATE Basic issue. February 1979 Basic-1 Added Section V, Space Station Project Documentation July 1987 Format and Preparation Guidelines. A General revision incorporating Change 1. March 1988 B General revision incorporating Supplement 1 and the metric August 1995 system of measurement. C Revised all sheets to incorporate simplified document November 15, 2004 formats and align them with automatic word processing software features. D Revised to incorporate an export control sign-off on the April 6, 2005 covers of documents and to remove the revision level designation for NPR 7120.5-compliant project plans. E General revision. August 3, 2015 F General revision and editorial update. July 8, 2017 ii APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE — DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED KSC-DF-107 Revision F CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope and Application.................................................................................... 1 1.3 Conventions of This Guide ............................................................................ -

01: Introduction to Technical Communication

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Open Technical Communication Open Educational Resources 7-1-2019 01: Introduction to Technical Communication Cassandra Race Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/opentc Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Race, Cassandra, "01: Introduction to Technical Communication" (2019). Open Technical Communication. 1. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/opentc/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Technical Communication by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1/8/2020 Introduction to Technical Writing Introduction to Technical Writing Cassandra Race Chapter Objectives Upon completion of this chapter, readers will be able to: 1. Define technical writing. 2. Summarize the six characteristics of technical writing. 3. Explain basic standards of good technical writing. The Nature of Technical Writing Did you know that you probably read or create technical communication every day without even realizing it? If you noticed signs on your way to work, checked the calories on the cereal box, emailed your professor to request a recommendation, or followed instructions to make a withdrawal from an ATM; you have been involved with technical, workplace, or professional communication. So what? You ask. Today, writing is a more important skill for professionals than ever before. The National Commission on Writing for Americas Families, Schools, and Colleges (2004) declares that writing today is not a frill for the few, but an essential skill for the many, and goes on to state that much of what is important in American public and economic life depends on strong written and oral communication skills. -

The First Wave (1953–1961) of the Professionalization Movement in Technical Communication Edward A

Applied Research The First Wave (1953–1961) of the Professionalization Movement in Technical Communication Edward A. Malone Abstract Purpose: To demonstrate that the professionalization of our field is a long-term project that has included achievements as well as setbacks and delays Methods: Archival research and analysis. Results: Many of the professionalization issues that we are discussing and pursuing today find their genesis – or at least have antecedents – in the work of the founders of the profession in the 1950s. Conclusions: Our appraisal of our professionalization gains must be tempered by a certain amount of realism and an awareness of the history of the professionalism movement in technical communication. Keywords: technical communication, history, professionalization, 1950s Practitioner’s • This study provides a consideration • It makes us better informed about takeaway of current professionalization issues the origin and early development in the context of their historical of the profession of technical development. communication in the United States. • It encourages us to temper our • It contributes to the creation of a enthusiasm and remain cautiously strong, shared historical consciousness optimistic about recent gains in the among members of the profession. quest for professional status and recognition. Introduction what possible consequences might result from our achieving full professional stature” (Savage, 1997, p. As a former president of the Society of Technical 34). The profession-building activities of the 1950s Writers and Publishers (STWP) noted, “There (e.g., the formation of professional organizations was a controversy in the early days. Was technical and journals, the writing of professional codes of writing really a profession? Did we want it to be a conduct, the creation of academic programs) were profession? If it was, how should we get other people attempts to professionalize technical communication. -

Has Technical Communication Arrived As a Profession?

APPLIED RESEARCH SUMMARY ᭜ Reports results of a practitioner survey on the definition of technical communication and the role of technology in their work ᭜ Argues that technical communication demonstrates a stable set of core values which suggest the field has a professional identity The Future Is the Past: Has Technical Communication Arrived as a Profession? KATHY PRINGLE AND SEAN WILLIAMS INTRODUCTION 139). In other words, like Grice and Krull, Davis sees n the May 2001 Technical communication, Roger technical communication as a profession with a dual iden- Grice and Robert Krull introduced a special issue on tity that involves some set of core skills that dovetail with the future of technical communication by outlining technological skills. Isome skills that participants at a 1997 conference at Davis doesn’t suggest what those core skills are, how- Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute had identified. From the ever, and Grice and Krull base their predictions on intuition list of things identified at that conference, Grice and Krull and conversations that occurred four years prior to the suggest that three categories run through all of the sugges- publication of their special issue. Some questions emerge tions. then. If we are going to postulate what the future of tech- 1. Technical communication will involve some kind nical communication holds, shouldn’t we understand what of information design skill, whether it’s testing, writing, is going on now? What is actually happening in the pro- visual design, or training. fession? What are practitioners in the profession actually 2. Technical communication will involve shifting doing? How do practitioners actually define the field and technological skills, including statistical testing, database their work? Likewise, shouldn’t we have an historical per- design, Web design, and authoring languages. -

Best Word Processor to Handle Large Documents

Best Word Processor To Handle Large Documents herSingle-handed crackdown Anthonycontrives always technically. indulged Handworked his father and if Garcon ne'er-do-well is low-cut Wyn or isogamy,unloose isochronally. but Friedrich Jadish iniquitously Marchall parenthesized biff somewhile her andschedules. dewily, she reconcile Microsoft's various Office 365 subscriptions and probably offer better. Top 6 Document Collaboration Tools In 2021 Bit Blog Bitai. Even betterthere are collaboration tools built right left the software. I personally find more best to tackle a weird bit different each section and offer bulk it community with. Allows you easy to perish with different tasks at the last time. Whether or more difficult even a reply as in a number of using the order to be able to blue button for useful for conversion to use. No matter how do bold, editing is not supported in both. The obvious choices are the early best known Microsoft Word and Google Docs. Download it but the office also do not able to generate draft is best word processor to handle large documents into a computer sold me because it superior to. How to concede Advantage of Microsoft Word enter Your Galaxy. How well Manage Large Documents in Word. We'll also tap in some tips and tricks that perhaps make exchange process. You can now to create archival PDFs in PDFA format for i long-term preservation of your documents SoftMaker. Home Mellel. 11 Word Processor Essentials That Every Student Needs to. You can in large document information quickly It offers live. Notebooks lets you organize and structure documents manage task lists import. -

1. Introduction: the Nature of Sexy Technical Writing

Kennesaw State University DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University Sexy Technical Communications Open Educational Resources 3-1-2016 1. Introduction: The aN ture of Sexy Technical Writing Cassandra Race Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm Part of the Technical and Professional Writing Commons Recommended Citation Race, Cassandra, "1. Introduction: The aN ture of Sexy Technical Writing" (2016). Sexy Technical Communications. 1. http://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/oertechcomm/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sexy Technical Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Nature of Sexy Technical Writing Introduction by Cassandra Race Sexy Technical Communication Home Introduction: The Nature of Sexy Technical Writing Did you know that you probably read or create technical communication every day without even realizing it? If you noticed signs on your way to work, checked the calories on the cereal box, emailed your professor to request a recommendation or followed instructions to make a withdrawal from an ATM, you have been involved with technical, workplace, or professional communication. So what? You ask. Today, writing is a more important skill for professionals than ever before. The National Commission on Writing for Americas Families, Schools, and Colleges (2004) declares that writing today is not a frill for the few, but an essential skill for the many,and goes on to state that much of what is important in American public and economic life depends on strong written and oral communication skills. -

How Are New Technologies Affecting the Technical Writer/Audience Relationship?

How are new technologies affecting the technical writer/audience relationship? Osha Roopnarine Department of Writing Studies, College of Liberal Arts Mentor: Dr. Ann Hill Duin for WRIT 8505 – Plan C Capstone Please address correspondence to Osha Roopnarine at [email protected], Department of Writing Studies, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN 55455. IRB Exempt: STUDY00002942 In partial fulfilment for a MS in Science and Technical Communication. © May 9th, 2018 Osha Roopnarine Technology, Technical Writer, Audience, Relationship Roopnarine Abstract This research investigates how the technical writer/audience relationship is affected by new technologies. The emergence of new technologies is occurring at a rapid pace and is changing the technical writer and audience relationship. The revised rhetorical triangle model by Lunsford and Ede (2009) does not adequately describe the relationship among these three dimensions (technology, writer, and audience). Therefore, I conducted an online survey with open-ended questions that were designed to gather opinions from an audience familiar with technical writing. I performed qualitative affinity mapping analysis of the responses to determine themes for the relationship among the writer, audience, and technology. I determined that new and emerging technologies are increasing the interaction of the audience with social media, wearables, augmented, and assistive technologies. This gives them easy access to new and archived information, which increases their cognition of the technological world. As a result, they seek alternate ways to comprehend technical information such as in choosing online technical manuals over the printed document, video tutorials over the written format, and opinions and evaluations of products from other users who are posting online. -

Contexts of Technical Communication Sponsored by ■■ Analysis of Industry Job Postings

November 2015 Volume 62 Number 4 CONTEXTS OF TECHNICAL COMMUNICATION SPONSORED BY ■ ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRY JOB POSTINGS ■ VISUALIZING A NON-PANDEMIC ■ APP ABROAD AND MUNDANE ENCOUNTERS ■ TRANSLATION AS A USER- LOCALIZATION PRACTICE 2015 release Adobe Tech Comm Tools MEET TOMORROW’S NEEDSTODAY Learn more Try now Request demo 2015 release 2015 release 2015 release 2015 release 2015 release Adobe Adobe Adobe Technical Adobe Adobe FrameMaker RoboHelp Communication Suite FrameMaker FrameMaker XML Author Publishing Server Adobe, the Adobe logo, and FrameMaker are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. © 2015 Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. Deliver a superior content consumption experience to end users with the new HTML5 layout Announcing the 2015 release of Adobe RoboHelp Dynamic content lters | New HTML5 layout | Mobile app output support | Modern ribbon UI Upgrade to the new Adobe RoboHelp (2015 release) for just US$399.00 Try Now Request Demo Request Info In the new release of Adobe RoboHelp, the latest HTML5 Responsive Layouts support Dynamic Filtering giving users the option to lter the content and see just what is relevant to them. Content Categories in WebHelp gave users the ability to choose sub-sets that had been dened by the author. Dynamic Filtering in HTML5 goes much further as the author can give more options and the user gets to choose which ones they want. Also the author can easily create an app in both iOS and Android formats.” Call 800 —Peter Grainge, Owner, www.grainge.org -833-6687 (Monday-Friday, 5am-7pm PST) Adobe, the Adobe logo, and RoboHelp are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. -

Documenting Library Work: Lessons We Can Learn from Technical Writers

Documenting Library Work: Lessons We Can Learn from Technical Writers Emily Nimsakont Amigos Library Services Cross Timbers Library Collaborative Conference August 7, 2020 Emily Nimsakont Cataloging and Metadata Trainer Amigos Library Services Certified Professional Technical Communicator through Society for Technical Communication The problem: why do we need documentation? Multiple people doing the same work Only one person knows how to do something Organizational changes What is a technical writer? “A writer who develops (writes, edits, curates, etc.) technical documents.” Morgan, K. (2015). Technical writing process: the simple, five-step process that can be used to create almost any piece of technical documentation such as a user guide, manual or procedures. St Leonards, NSW: Better On Paper Publications. What is a technical document? “A document of a technical nature which assists someone to carry out a process or procedure, or use a product. Examples of technical documents include user guides, procedures, manuals and quick reference guides.” Morgan, K. (2015). Technical writing process: the simple, five- step process that can be used to create almost any piece of technical documentation such as a user guide, manual or procedures. St Leonards, NSW: Better On Paper Publications. How can technical writing help? “Technical writing is a definable, repeatable, predictable process. It can be planned, scheduled, and executed in a manner that leads to predictable outcomes, quality, and timing.” Morgan, K. (2015). Technical writing process: the simple, five- step process that can be used to create almost any piece of technical documentation such as a user guide, manual or procedures. St Leonards, NSW: Better On Paper Publications.