Image by William Rebsamen, Used by Permission © 2002, William Rebasamen Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waco Mammoth Site • Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment • Texas Waco Mammoth Site Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment

Waco Mammoth Site Waco National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Waco Mammoth Site • Special Resource Study / Environmental Assessment • Texas Waco Mammoth Site Special Resource Study Special Resource / Environmental Assessment Environmental National Park Service • United States Department of the Interior Special Resource Study/Environmental Assessment Texas July • 2008 As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources; protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national This report has been prepared to provide Congress and the public with information about parks and historical places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor the resources in the study area and how they relate to criteria for inclusion within the recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to ensure national park system. Publication and transmittal of this report should not be considered an that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging stewardship endorsement or a commitment by the National Park Service to seek or support either and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for specific legislative authorization for the project or appropriation for its implementation. American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under Authorization and funding for any new commitments by the National Park Service will have U.S. administration. to be considered in light of competing priorities for existing units of the national park system and other programs. -

Inside the 'Hermit Kingdom'

GULF TIMES time out MONDAY, AUGUST 10, 2009 Inside the ‘Hermit Kingdom’ A special report on North Korea. P2-3 time out • Monday, August 10, 2009 • Page 3 widespread human rights abuses, to the South Korean news agency Traffi c lights are in place, but rarely is a luxury. although many of their accounts Yonhap, he has described himself as used. North Korea has a long history of inside date back to the 1990s. an Internet expert. Pyongyang’s eight cinemas are tense relations with other regional According to a report from the He is thought to have fi nally said to be frequently closed due powers and the West — particularly UN High Commission for Human annointed the youngest of his three to lack of power; when open, they since it began its nuclear Rights this year: “The UN General sons Kim Jong-un as his heir and screen domestic propaganda movies programme. China is regarded Assembly has recognised and “Brilliant Comrade”, following with inspiring titles such as The Fate as almost its sole ally; even so, condemned severe Democratic his reported stroke last year. Even of a Self-Defence Corps Man. relations are fraught, based as much People’s Republic of Korea human less is known about this leader- The state news agency KCNA as anything on China’s fear that rights violations including the in-waiting. Educated in Bern, runs a curious combination of brief the collapse of the current regime use of torture, public executions, Switzerland, the 25-year-old is said news items such as its coverage of could lead to a fl ood of refugees and extrajudicial and arbitrary to be a basketball fan. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

Educator Guide Presented by the Field Museum

at the San Diego Natural History Museum July 4-November 11, 2013 Educator Guide Presented by The Field Museum INSIDE: Exhibition Introduction • Planning Your Visit Gallery Overviews and Guiding Questions • Focused Field Trip Activities Correlations to California State Content Standards • Additional Resources Mammoths and Mastodons: Titans of the Ice Age at the San Diego Natural History Museum is supported by: City of San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture County of San Diego Board of Supervisors, Community Enhancement Program Walter J. and Betty C. Zable Foundation Qualcomm Foundation The Kenneth T. and Eileen L. Norris Foundation VWR Charitable Foundation Education Sponsor: The Field Museum gratefully acknowledges the collaboration and assistance of the Shemanovskii Regional Museum and Exhibition Complex and the International Mammoth Committee. Walking Map The Field Museum • Mammoths and Mastodons Educator Guide • fieldmuseum.org/mammoths Page 2 www.sdnhm.org/mammoths-mastodons Exhibition Introduction Mammoths and Mastodons: Titans of the Ice Age July 4–November 11, 2013 Millions of years ago, colossal mammals roamed Europe, Asia, and North America. From the gigantic mammoth to the massive mastodon, these creatures have captured the world’s fascination. Meet “Lyuba,” the best-preserved baby mammoth in the world, and discover all that we’ve learned from her. Journey back to the Ice Age through monumental video installations, roam among saber-toothed cats and giant bears, and wonder over some of the oldest human artifacts in existence. Hands-on exciting interactive displays reveal the difference between a mammoth and a mastodon, This sketch shows a Columbian mammoth, an offer what may have caused their extinction, and show African elephant, and an American mastodon how today’s scientists excavate, analyze, and learn more (from back to front). -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Beast of Boggy Creek the True Story

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Beast of Boggy Creek The True Story of the Fouke Monster by Lyle Blackburn The Beast of Boggy Creek The True Story of the Fouke Monster by Lyle Blackburn. Take look inside Lyle's monster office in this special tour: American Monster Tour: Oklahoma Demon Flyer This is the unaired, pilot episode for a show hosted by Lyle Blackburn and Ken Gerhard: Sinister Swamps: Monsters and Mysteries from the Mire - book promo: Momo: The Strange Case of the Missouri Monster - book promo: Beyond Boggy Creek: In Search of the Southern Sasquatch - book promo: Beast of Boggy Creek: The True Story of the Fouke Monster - book promo: Boggy Creek Monster - documentary film about the history of The Legend of Boggy Creek: Monsters and Mysteries in America - the Fouke Monster segment featuring Lyle: This is a news report about the Lake Worth Monster which ran on WFAA TV in Fort Worth / Dallas, Texas in the summer of 1969: The Beast of Boggy Creek The True Story of the Fouke Monster by Lyle Blackburn. The Beast of Boggy Creek The True Story of the Fouke Monster. by Lyle Blackburn Foreword by Loren Coleman Hardcover, Trade Paperback, eBook / Anomalist Books 258 pages / 37 photos / 17 illustrations. This is the definitive guide to Fouke's Boggy Creek Monster by author and researcher, Lyle Blackburn. The book covers the history of the Fouke Monster and the making of The Legend of Boggy Creek movie. The book also includes a sighting chronicle with over 70 visual encounters near Fouke, Arkansas. It also contains a breakdown of all Legend of Boggy Creek scenes, tracing them back to the actual sightings on which they were based! Beyond Boggy Creek In Search of the Southern Sasquatch. -

As a New Crop of Baby Animals

Expert Guidance on Children’s Interactive Media May 2009 Volume 17, No. 5, Issue 110 Bugsby Reading System Cate West: The Vanishing Files Circus Games Crayola Colorful Journey Curious George’s Dictionary DanceDanceRevolution Disney Grooves Donkey Kong Jungle Beat Elizabeth Find, MD: Diagnosis Mystery Emergency! Disaster Rescue Squad Excitebots: Trick Racing Faceland Free Realms Grand Slam Tennis Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Hell’s Kitchen Intel ClassMate Convertible PC Jewel Master: Cradle of Rome Kids Collection DVDs LEGO Education: WeDo Robotics LEGO Rock Band M&M’s Beach Party Madden NFL 10 Mortimer Beckitt and the Secrets of Spooky Manor NCAA Football 10 Nitro Jr. Notebook Nitro Tunes Desktop PuttingPutting thethe OMG! High School Triple Play Pack Paper Show PebbleGo APTOP PeeWee Pivot Tablet Laptop ““LL”” Penguin Cold Cash Professor Heinz Wolff’s Gravity Ride & Learn Giraffe Bike Rosetta Stone Version 3, Level 1: inin OLPCONE LAPTOP PER CHILD Italian OLPC SCRABBLE The Atom Powered Intel ClassMate Convertable PC Secret Saturdays Sims 3, The Step & Count Kangaroo DDR Disney Grooves, Help for Baby Animals, Curious George on an iPhone, Talking Pens and more.... Super Secret (www.supersecret.com) Tiger Woods PGA Tour 10 TouchMaster 2 Up! V.Smile Smartridges for 2009 One Laptop Per Doctor “Mr. Buckleitner?” My doctor peered into the waiting room, juggling a battered HP Laptop TM in one arm. The computer was clearly both a nuisance and a necessity that had earned a May 2009 proper place in the medical routine. Volume 17, No. 5, Issue 110 As the blood pressure monitor tightened EDITOR Warren Buckleitner, Ph.D., around my arm, I asked about the laptop. -

Newsletter 12/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 12/09 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 254 - Juli 2009 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 12/09 (Nr. 254) Juli 2009 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Hoher Besuch aus England: Der neue Newsletter kommt mal wieder et- Kinotechnikspezialist was unpünktlich in Ihren Briefkasten (ob Duncan bei Laser Hotline elektronisch oder in Papierform) geflattert. Und das nicht ohne Grund. Denn just als wir die aktuelle Ausgabe beenden wollten, gab es einen Überraschungsbesuch aus England. Duncan McGregor, seines Zeichens Chefvor- führer des berühmten Pictureville Cinema in Bradford, nutzte seinen Urlaub in Deutsch- land zu einer Stippvisite bei der Laser Hotline in Korntal. Eigentlich logisch, dass es da nicht nur bei einer Stippvisite blieb, wo man sich doch soviel Neues aus der Welt des Films im Speziellen und der Kinotechnik im Besonderen zu erzählen hatte. Und unser Heimkino hatte es ihm ganz offensichtlich angetan. Der Sound gefiel dem Spezialisten so gut, dass er immer mehr sehen und vor allem hören wollte. Dieser Wunsch wurde ihm natürlich nicht verweigert. So kam es, dass der Newsletter etwas auf der Strecke blieb. Der Experte beim Hörtest: unser Heimkino ist jetzt Einer unserer Geheimtipps liefert dieses Mal „Duncan“-approved! das Titelbild für den aktuellen Newsletter. Wer DER KNOCHENMANN im Kino verpasst hat, der darf sich jetzt bereits auf September freuen. Denn dann wird Josef Bierbichler als Inhaber eines österreichischen Landgasthofes weiter sein Unwesen auf DVD treiben. -

Children's Catalog 2020-2021

CHILDREN’S CATALOG | 2020-2021 CONTENTS 01 New Titles 15 Juvenile Fiction 22 Juvenile Non Fiction 165 Sales Representatives 167 Title Index pages 174 Author Index pages 175 Order Info from Graham Nash OUR HOUSE BY GRAHAM NASH, ILLUSTRATED BY HUGH SYME, FOREWORD BY CAROLE KING more information on page 11! NEW TITLES The Generous Fish BY JACQUELINE JULES, ILLUSTRATED BY FRANCES TYRRELL Inspired by Jewish folklore, The Generous Fish is the story of a young boy named Reuven who takes a verse from scripture to “cast your bread upon the waters” (Ecclesiastes 11:1) quite literally. The result of his daily act is a giant talking fish with golden scales! Boy and fish spend idyllic days together until the villagers realize those scales are real gold. Every villager has good reason to ask for one. Devorah needs clothes for her children. Old Joseph needs money for a cane. The fish says he has plenty to share. But he grows weak from giving away too much, too fast. Can Reuven stand up to the village and save his friend? Jacqueline Jules is the author of forty books for young readers, including the award-winning Zapato Power series, Never Say a Mean Word Again: A Tale from Medieval Spain, and Feathers for Peacock. A former school librarian and teacher, Jacqueline enjoys visiting schools to share her passion for reading and writing. She is a word person, who loves rearranging words on the page, the same way people have fun fitting the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle together. Jacqueline lives in Arlington, Virginia. -

The History of Middlesex County Ended As the County’S Original Settlers Were Permanently Displaced by the European Newcomers

HISTORY BUFF’S THETHE HITCHHIKER’SHITCHHIKER’S GUIDEGUIDE TOTO MIDDLESEXMIDDLESEX COUNTYCOUNTY “N.E. View of New Brunswick, N.J.” by John W. Barber and Henry Howe, showing the Delaware and Raritan Canal, Raritan River, and railroads in the county seat in 1844. Thomas A. Edison invented the Phonograph at Menlo Park (part of Edison) in 1877. Thomas Edison invented the incandescent Drawing of the Kilmer oak tree by Joan Labun, New Brunswick, 1984. Tree, which light bulb at Menlo Park (part of Edison) in inspired the Joyce Kilmer poem “Trees” was located near the Rutgers Labor Education 1879. Center, just south of Douglass College. Carbon Filament Lamp, November 1879, drawn by Samuel D. Mott MIDDLESEX COUNTY BOARD OF CHOSEN FREEHOLDERS Christopher D. Rafano, Freeholder Director Ronald G. Rios, Deputy Director Carol Barrett Bellante Stephen J. Dalina H. James Polos Charles E. Tomaro Blanquita B. Valenti Compiled and written by: Walter A. De Angelo, Esq. County Administrator (1994-2008) The following individuals contributed to the preparation of this booklet: Clerk of the Board of Chosen Freeholders Margaret E. Pemberton Middlesex County Cultural & Heritage Commission Anna M. Aschkenes, Executive Director Middlesex County Department of Business Development & Education Kathaleen R. Shaw, Department Head Carl W. Spataro, Director Stacey Bersani, Division Head Janet Creighton, Administrative Assistant Middlesex County Office of Information Technology Khalid Anjum, Chief Information Officer Middlesex County Administrator’s Office John A. Pulomena, County Administrator Barbara D. Grover, Business Manager Middlesex County Reprographics Division Mark F. Brennan, Director Janine Sudowsky, Graphic Artist ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... Page 1 THE NAME ................................................................................... Page 3 THE LAND .................................................................................. -

How Did 90% of Large Australian Ice Age Animals Go Extinct? Michael J

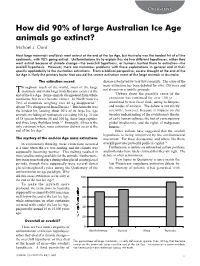

Overviews How did 90% of large Australian Ice Age animals go extinct? Michael J. Oard Most large mammals and birds went extinct at the end of the Ice Age, but Australia was the hardest hit of all the continents, with 90% going extinct. Uniformitarians try to explain this via two different hypotheses: either they went extinct because of climate change—the overchill hypothesis, or humans hunted them to extinction—the overkill hypothesis. However, there are numerous problems with these explanations in general and in their specific applicability to the Australian extinctions. From a biblical perspective, severe drought at the end of the Ice Age is likely the primary factor that caused the severe extinction event of the large animals in Australia. The extinction record disease is believed by very few scientists. The cause of the mass extinction has been debated for over 150 years and hroughout much of the world, most of the large Tmammals and many large birds became extinct at the not always on scientific grounds: end of the Ice Age. Some animals disappeared from whole ‘Debate about the possible cause of the continents, but never became extinct. In North America extinction has continued for over 150 yr … , 70% of mammals weighing over 40 kg disappeared.1,2 stimulated by new fossil finds, dating techniques, About 75% disappeared from Eurasia.3 But Australia was and modes of analysis. The debate is not strictly the hardest hit, loosing about 90% of its large Ice Age scientific, however, because it impacts on the animals, including all marsupials -

People Are Seeing Something

PEOPLE ARE SEEING SOMETHING A SURVEY OF LAKE MONSTERS IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA BY DENVER MICHAELS © 2016 DENVER MICHAELS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. www.denvermichaels.net Author’s Note This book is an updated version published in May 2016. This update addresses formatting issues and did not alter the content of the original in any way. Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: The Northwestern Region .................................. 5 The Ogopogo: Canada’s Loch Ness Monster ..................................... 6 Okanagan Lake: Home of the Ogopogo ............................................. 6 Native Legends ................................................................................... 6 Ogopogo Sightings ............................................................................. 7 Mass Sightings .................................................................................... 8 Notable Sightings ............................................................................... 8 Tangible Visual Evidence .................................................................... 9 “A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words” .......................................... 10 Video Evidence ................................................................................. 11 What is the Ogopogo?...................................................................... 13 Shuswaggi ...................................................................................