A Multi-Scale Computational Model of the Effects of TMS on Motor Cortex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans Ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai To cite this version: Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai. Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, Frontiers, 2018, 12, pp.93. 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093. hal-01929541 HAL Id: hal-01929541 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01929541 Submitted on 21 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REVIEW published: 19 November 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093 Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans J. ten Donkelaar 1*†, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer 2† and Jürgen K. Mai 3† 1 Department of Neurology, Donders Center for Medical Neuroscience, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2 IMN Institut des Maladies Neurodégénératives UMR 5293, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 3 Institute for Anatomy, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany The gyri and sulci of the human brain were defined by pioneers such as Louis-Pierre Gratiolet and Alexander Ecker, and extensified by, among others, Dejerine (1895) and von Economo and Koskinas (1925). -

Stimulus Arousal Drives Amygdalar Responses to Emotional

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Stimulus arousal drives amygdalar responses to emotional expressions across sensory modalities Huiyan Lin1,2,4*, Miriam Müller-Bardorf2,4, Bettina Gathmann2,4, Jaqueline Brieke2, Martin Mothes-Lasch2, Maximilian Bruchmann2, Wolfgang H. R. Miltner3 & Thomas Straube2 The factors that drive amygdalar responses to emotionally signifcant stimuli are still a matter of debate – particularly the proneness of the amygdala to respond to negatively-valenced stimuli has been discussed controversially. Furthermore, it is uncertain whether the amygdala responds in a modality-general fashion or whether modality-specifc idiosyncrasies exist. Therefore, the present functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study systematically investigated amygdalar responding to stimulus valence and arousal of emotional expressions across visual and auditory modalities. During scanning, participants performed a gender judgment task while prosodic and facial emotional expressions were presented. The stimuli varied in stimulus valence and arousal by including neutral, happy and angry expressions of high and low emotional intensity. Results demonstrate amygdalar activation as a function of stimulus arousal and accordingly associated emotional intensity regardless of stimulus valence. Furthermore, arousal-driven amygdalar responding did not depend on the visual and auditory modalities of emotional expressions. Thus, the current results are consistent with the notion that the amygdala codes general stimulus relevance across visual -

Translingual Neural Stimulation with the Portable Neuromodulation

Translingual Neural Stimulation With the Portable Neuromodulation Stimulator (PoNS®) Induces Structural Changes Leading to Functional Recovery In Patients With Mild-To-Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury Authors: Jiancheng Hou,1 Arman Kulkarni,2 Neelima Tellapragada,1 Veena Nair,1 Yuri Danilov,3 Kurt Kaczmarek,3 Beth Meyerand,2 Mitchell Tyler,2,3 *Vivek Prabhakaran1 1. Department of Radiology, School of Medicine and Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA 2. Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA 3. Department of Kinesiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA *Correspondence to [email protected] Disclosure: Dr Tyler, Dr Danilov, and Dr Kaczmarek are co-founders of Advanced Neurorehabilitation, LLC, which holds the intellectual property rights to the PoNS® technology. Dr Tyler is a board member of NeuroHabilitation Corporation, a wholly- owned subsidiary of Helius Medical Technologies, and owns stock in the corporation. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest. Acknowledgements: Professional medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Kelly M. Fahrbach, Ashfield Healthcare Communications, part of UDG Healthcare plc, funded by Helius Medical Technologies. Dr Tyler, Dr Kaczmarek, Dr Danilov, Dr Hou, and Dr Prabhakaran were being supported by NHC-TBI-PoNS-RT001. Dr Hou, Dr Kulkarni, Dr Nair, Dr Tellapragada, and Dr Prabhakaran were being supported by R01AI138647. Dr Hou and Dr Prabhakaran were being supported by P01AI132132, R01NS105646. Dr Kulkarni was being supported by the Clinical & Translational Science Award programme of the National Center for Research Resources, NCATS grant 1UL1RR025011. Dr Meyerand, Dr Prabhakaran, Dr Nair was being supported by U01NS093650. -

1. Lateral View of Lobes in Left Hemisphere TOPOGRAPHY

TOPOGRAPHY T1 Division of Cerebral Cortex into Lobes 1. Lateral View of Lobes in Left Hemisphere 2. Medial View of Lobes in Right Hemisphere PARIETAL PARIETAL LIMBIC FRONTAL FRONTAL INSULAR: buried OCCIPITAL OCCIPITAL in lateral fissure TEMPORAL TEMPORAL 3. Dorsal View of Lobes 4. Ventral View of Lobes PARIETAL TEMPORAL LIMBIC FRONTAL OCCIPITAL FRONTAL OCCIPITAL Comment: The cerebral lobes are arbitrary divisions of the cerebrum, taking their names, for the most part, from overlying bones. They are not functional subdivisions of the brain, but serve as a reference for locating specific functions within them. The anterior (rostral) end of the frontal lobe is referred to as the frontal pole. Similarly, the anterior end of the temporal lobe is the temporal pole, and the posterior end of the occipital lobe the occipital pole. TOPOGRAPHY T2 central sulcus central sulcus parietal frontal occipital lateral temporal lateral sulcus sulcus SUMMARY CARTOON: LOBES SUMMARY CARTOON: GYRI Lateral View of Left Hemisphere central sulcus postcentral superior parietal superior precentral gyrus gyrus lobule frontal intraparietal sulcus gyrus inferior parietal lobule: supramarginal and angular gyri middle frontal parieto-occipital sulcus gyrus incision for close-up below OP T preoccipital O notch inferior frontal cerebellum gyrus: O-orbital lateral T-triangular sulcus superior, middle and inferior temporal gyri OP-opercular Lateral View of Insula central sulcus cut surface corresponding to incision in above figure insula superior temporal gyrus Comment: Insula (insular gyri) exposed by removal of overlying opercula (“lids” of frontal and parietal cortex). TOPOGRAPHY T3 Language sites and arcuate fasciculus. MRI reconstruction from a volunteer. central sulcus supramarginal site (posterior Wernicke’s) Language sites (squares) approximated from electrical stimulation sites in patients undergoing operations for epilepsy or tumor removal (Ojeman and Berger). -

Gray Matter Volume Changes Following Antipsychotic Therapy in First

Journal of Psychiatric Research 116 (2019) 126–132 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Psychiatric Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpsychires Gray matter volume changes following antipsychotic therapy in first-episode schizophrenia patients: A longitudinal voxel-based morphometric study T Fan Guoa,b,1, Yuan-Qiang Zhua,1, Chen Lia,1, Xing-Rui Wanga, Hua-Ning Wangd, Wen-Ming Liud, ∗ ∗∗ Liu-Xian Wanga,c, Ping Tiana, Xiao-Wei Kanga, Long-Biao Cuia,e, Yi-Bin Xia, , Hong Yina, a Department of Radiology, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an, 710032, China b Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100190, China c Department of Radiology, Chinese PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China d Department of Psychiatry, Xijing Hospital, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an, 710032, China e Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Medical Psychology, Fourth Military Medical University, Xi'an, 710032, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Despite evidence of structural brain abnormalities in schizophrenia, the current study aimed to explore the Schizophrenia effects of antipsychotic treatment on gray matter (GM) volume using structural magnetic resonance imaging Voxel-based morphometry (MRI) and investigate the relationship between brain structure and treatment response. The GM volumes of 33 Antipsychotics patients with first-episode schizophrenia were calculated with voxel-based morphometry (VBM), with 33 mat- Magnetic resonance imaging ched healthy controls. Longitudinal volume changes within subjects after 4-month antipsychotic treatment were First-episode also evaluated. Correlation between volumetric changes and clinical symptoms derived from the Positive and Gray matter volume Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) were further investigated. -

A Practical Review of Functional MRI Anatomy of the Language and Motor Systems

REVIEW ARTICLE FUNCTIONAL A Practical Review of Functional MRI Anatomy of the Language and Motor Systems X V.B. Hill, X C.Z. Cankurtaran, X B.P. Liu, X T.A. Hijaz, X M. Naidich, X A.J. Nemeth, X J. Gastala, X C. Krumpelman, X E.N. McComb, and X A.W. Korutz ABSTRACT SUMMARY: Functional MR imaging is being performed with increasing frequency in the typical neuroradiology practice; however, many readers of these studies have only a limited knowledge of the functional anatomy of the brain. This text will delineate the locations, anatomic boundaries, and functions of the cortical regions of the brain most commonly encountered in clinical practice—specifically, the regions involved in movement and language. ABBREVIATIONS: FFA ϭ fusiform face area; IPL ϭ inferior parietal lobule; PPC ϭ posterior parietal cortex; SMA ϭ supplementary motor area; VOTC ϭ ventral occipitotemporal cortex his article serves as a review of the functional areas of the brain serving to analyze spatial position and the ventral stream working Tmost commonly mapped during presurgical fMRI studies, to identify what an object is. Influenced by the dorsal and ventral specifically targeting movement and language. We have compiled stream model of vision, Hickok and Poeppel2 hypothesized a sim- what we hope is a useful, easily portable, and concise resource that ilar framework for language. In this model, the ventral stream, or can be accessible to radiologists everywhere. We begin with a re- lexical-semantic system, is involved in sound-to-meaning map- view of the language-processing system. Then we describe the pings associated with language comprehension and semantic ac- gross anatomic boundaries, organization, and function of each cess. -

Seed MNI Coordinates Lobe

MNI Coordinates Seed Lobe (Hemisphere) Region BAa X Y Z FP1 -18 62 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FPz 4 62 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FP2 24 60 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 10 AF7 -38 50 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF3 -30 50 24 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 9 AFz 4 58 30 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 9 AF4 36 48 20 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF8 42 46 -4 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 10 F7 -48 26 -4 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 F5 -48 28 18 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 45 F3 -38 28 38 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 9 F1 -20 30 50 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 Fz 2 32 54 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F2 26 32 48 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F4 42 30 34 Frontal Lobe (R) Precentral Gyrus 9 F6 50 28 14 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 46 F8 48 24 -8 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 FT9 -50 -6 -36 Temporal Lobe (L) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 FT7 -54 2 -8 Temporal Lobe (L) Superior Temporal Gyrus 22 FC5 -56 4 22 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 6 FC3 -44 6 48 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC1 -22 6 64 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FCz 4 6 66 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 6 FC2 28 8 60 Frontal Lobe (R) Sub-Gyral 6 FC4 48 8 42 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC6 58 6 16 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 44 FT8 54 2 -12 Temporal Lobe (R) Superior Temporal Gyrus 38 FT10 50 -6 -38 Temporal Lobe (R) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 T7/T3 -

Table S1. Peak Coordinates of the Regions Involved in the Task Main

Table S1. Peak coordinates of the regions involved in the task main network Number of MNI p FDR Anatomical description T voxels coordinates corrected x y z Left superior temporal gyrus 2753 -58 -16 -4 16.5 0.0000002 Left middle temporal gyrus Left rolandic operculum Left superior temporal pole Left Heschl gyrus Left inferior frontal gyrus Left supramarginal gyrus Left insula Right superior temporal gyrus 1613 62 -4 -6 14.9 0.0000002 Right middle temporal gyrus Right superior temporal pole Right Heschl gyrus Right rolandic operculum Bilateral cerebellum 565 6 -58 12 11.5 0.0000009 Right lingual gyrus Left precentral gyrus 1682 -34 -26 62 9.55 0.000004 Left postcentral gyrus Left inferior parietal gyrus Bilateral supplementary motor areas 554 -2 10 54 9.2 0.000006 Right middle cingulate gyrus Left medial superior frontal gyrus Right precentral gyrus 24 56 4 44 6.9 0.00007 Left putamen 66 -24 -6 44 6.6 0.0001 Left pallidum Left thalamus 70 -12 -20 -2 6.4 0.0001 Left inferior frontal gyrus 11 -44 24 16 6.1 0.0002 Left calcarine fissure 20 -4 -74 8 6.08 0.0002 Left lingual gyrus Left superior temporal pole 17 -38 6 -18 6.05 0.0002 Left putamen 36 -28 -24 -8 5.8 0.0003 Table S2. Peak coordinates of the regions showing a main effect of item type Number of MNI p FDR Anatomical description T voxels coordinates corrected x y z Words – Pseudowords Left inferior frontal gyrus 96 -40 24 -6 7.6 0.000001 Left insula Left superior temporal pole Left middle temporal gyrus 141 -56 -36 -2 5.9 0.000015 Left precentral gyrus 26 -50 8 32 4.9 0.00025 Left inferior -

The Effects of Pharmacological Opioid Blockade on Neural Measures of Drug Cue-Reactivity in Humans

Neuropsychopharmacology (2016) 41, 2872–2881 © 2016 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/16 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org The Effects of Pharmacological Opioid Blockade on Neural Measures of Drug Cue-Reactivity in Humans 1 2 ,1,2 Kelly E Courtney , Dara G Ghahremani and Lara A Ray* 1 2 Department of Psychology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA Interactions between dopaminergic and opioidergic systems have been implicated in the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse. The present study investigated the effects of opioid blockade, via naltrexone, on functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) measures during methamphetamine cue-reactivity to elucidate the role of endogenous opioids in the neural systems underlying drug craving. To investigate = = = this question, non-treatment seeking individuals with methamphetamine use disorder (N 23; 74% male, mean age 34.70 (SD 8.95)) were recruited for a randomized, placebo controlled, within-subject design and underwent a visual methamphetamine cue-reactivity task during two blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) fMRI sessions following 3 days of naltrexone (50 mg) and matched time for placebo. fMRI analyses tested naltrexone-induced differences in BOLD activation and functional connectivity during cue processing. The results showed that naltrexone administration reduced cue-reactivity in sensorimotor regions and related to altered functional connectivity of dorsal striatum, ventral tegmental area, and precuneus with frontal, visual, sensory, and motor-related regions. Naltrexone also weakened the associations between subjective craving and precuneus functional connectivity with sensorimotor regions and strengthened the associations between subjective craving and dorsal striatum and precuneus connectivity with frontal regions. -

Brain Anatomy

BRAIN ANATOMY Adapted from Human Anatomy & Physiology by Marieb and Hoehn (9th ed.) The anatomy of the brain is often discussed in terms of either the embryonic scheme or the medical scheme. The embryonic scheme focuses on developmental pathways and names regions based on embryonic origins. The medical scheme focuses on the layout of the adult brain and names regions based on location and functionality. For this laboratory, we will consider the brain in terms of the medical scheme (Figure 1): Figure 1: General anatomy of the human brain Marieb & Hoehn (Human Anatomy and Physiology, 9th ed.) – Figure 12.2 CEREBRUM: Divided into two hemispheres, the cerebrum is the largest region of the human brain – the two hemispheres together account for ~ 85% of total brain mass. The cerebrum forms the superior part of the brain, covering and obscuring the diencephalon and brain stem similar to the way a mushroom cap covers the top of its stalk. Elevated ridges of tissue, called gyri (singular: gyrus), separated by shallow groves called sulci (singular: sulcus) mark nearly the entire surface of the cerebral hemispheres. Deeper groves, called fissures, separate large regions of the brain. Much of the cerebrum is involved in the processing of somatic sensory and motor information as well as all conscious thoughts and intellectual functions. The outer cortex of the cerebrum is composed of gray matter – billions of neuron cell bodies and unmyelinated axons arranged in six discrete layers. Although only 2 – 4 mm thick, this region accounts for ~ 40% of total brain mass. The inner region is composed of white matter – tracts of myelinated axons. -

Core-Example1.Pdf

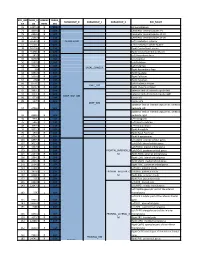

ROI_IND NUM_V HEMISP TISSUE_ SUBGROUP_0 SUBGROUP_1 SUBGROUP_2 ROI_NAME EX OX HERE SEG 95 12871.8 B WM corpus callosum 71 4899.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules I-V 73 2858.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIII-X 72 2266.9 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VI-VII 39 54582.6 L GM CEREBELLUM Left Cerebellum Exterior 41 15500.7 L WM Left Cerebellum White Matter 38 54379.4 R GM Right Cerebellum Exterior 40 15458.7 R WM Right Cerebellum White Matter 30 585.9 L GM Left Accumbens Area 37 3578.9 L GM Left Caudate 56 1597.6 L GM Left Pallidum 58 4942.3 L GM Left Putamen BASAL_GANGLIA 23 526 R GM Right Accumbens Area 36 3651.5 R GM Right Caudate 55 1638.8 R GM Right Pallidum 57 4726 R GM Right Putamen 60 8574.1 L GM Left Thalamus Proper DEEP_GM 59 8256.3 R GM Right Thalamus Proper 92 2887.7 L WM anterior limb of internal capsule left 91 3393.3 R WM anterior limb of internal capsule right DEEP_WM_GM 90 673.6 L WM fornix left 89 517.5 R WM fornix right DEEP_WM posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 94 2416.3 L WM peduncle left posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 93 2480.5 R WM peduncle right 32 993.7 L GM Left Amygdala 75 586.5 L GM Left Basal Forebrain 48 3597.7 L GM Left Hippocampus 31 1021.3 R GM Right Amygdala 76 593.1 R GM Right Basal Forebrain 47 3704.7 R GM Right Hippocampus 105 1897.7 L GM Left AOrG anterior orbital gyrus 137 3015.9 L GM Left LOrG lateral orbital gyrus 147 4637.3 L GM Left MOrG medial orbital gyrus 179 2915.7 L GM FRONTAL_INFERIOR_G Left POrG posterior orbital gyrus 104 2244.9 R GM M Right AOrG anterior orbital -

Brain Structure Changes Associated with Sexual Orientation Mikhail Votinov1,2*, Katharina S

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Brain structure changes associated with sexual orientation Mikhail Votinov1,2*, Katharina S. Goerlich3, Andrei A. Puiu2, Elke Smith4, Thomas Nickl‑Jockschat5,6, Birgit Derntl7 & Ute Habel1,2 Biological sex diferences in brain function and structure are reliably associated with several cortico‑subcortical brain regions. While sexual orientation (hetero‑ versus homosexuality) has been similarly linked to functional diferences in several phylogenetically‑old brain areas, the research on morphological brain phenotypes associated with sexual orientation is far from conclusive. We examined potential cerebral structural diferences linked to sexual orientation in a group of 74 participants, including 37 men (21 homosexual) and 37 women (19 homosexual) using voxel‑based morphometry (VBM). Gray matter volumes (GMV) were compared with respect to sexual orientation and biological sex across the entire sample using full factorial designs controlling for total intracranial volume, age, handedness, and education. We observed a signifcant efect of sexual orientation for the thalamus and precentral gyrus, with more GMV in heterosexual versus homosexual individuals, and for the putamen, with more GMV in homosexual + than heterosexual individuals. We found signifcant interactions between biological sex and sexual orientation, indicating that the signifcant efect for the putamen cluster was driven by homosexual women, whereas heterosexual women had increased precentral gyrus GMV. Heterosexual men exhibited more GMV in the thalamus than homosexual men. This study shows that sexual orientation is refected in brain structure characteristics and that these difer between the sexes. The results emphasize the need to include or control for potential efects of participants’ sexual orientation in neuroimaging studies. Furthermore, our fndings provide important new insights into the brain morphology underlying sexual orientation and likely have important implications for understanding brain functions and behavior.