David and Shimei: Innocent Victim and Perpetrator?1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel Teaching Letter

BRIDGES FOR PEACE Israel Teaching Letter Vol. # 770410 April 2010 Bridges for Peace Your Israel Connection ® n International Headquarters P.O. Box 1093 Jerusalem, Israel Tel: (972) 2-624-5004 [email protected] n Australia P.O. Box 1785, Buderim Queensland 4556 Tel: 07-5453-7988 [email protected] n Canada P.O. Box 21001, RPO Charleswood Winnipeg, MB R3R 3R2 Tel: 204-489-3697, [email protected] n Japan Taihei Sakura Bldg. 5F 4-13-2 Taihei, Sumida-Ku Tokyo 130 0012 Tel: 03-5637-5333, [email protected] n New Zealand P.O. Box 10142 Te Mai, Whangarei Tel: 09-434-6527 [email protected] n South Africa P.O. Box 1848 Durbanville 7551 Tel: 021-975-1941 [email protected] n United Kingdom 11 Bethania Street, Maesteg Bridgend, Wales CF34 9DJ Tel: 01656-739494 [email protected] n United States P.O. Box 410037 Melbourne, FL 32941-0037 Tel: 800-566-1998 Product orders: 888-669-8800 [email protected] www.bridgesforpeace.com 1 GUARD YOUR TONGUE “STICKS AND STONES MAY BREAK YOUR BONES, but words will never hurt you.” Have you ever heard this seemingly innocent childhood taunt? Perhaps you’ve even used it yourself in response to some unkind phrase or words. Most of us, at some point in our lives, have both said something bad about another per- son and have had another person say something bad about us. We tend to think that what we said really didn’t hurt the other person, but we also tend to long remember the hurt that another person’s words have caused us. -

“King Selection” 1 Kings 1-2 January 8, 2017 INTRODUCTION: As The

“King Selection” 1 Kings 1-2 January 8, 2017 INTRODUCTION: As the book of Kings opens, Israel is at a time of uncertainty. The great King David is obviously fading and not long for this life. That’s the point of the opening verses of the book. In the words of one commentary, David is old and cold. His servants try covering him with more clothes, but he is still cold. Then they have another idea. They want to add to his harem the most beautiful woman they can find. Something like a beauty pageant is held, and a woman by the name of Abishag is selected as the most beautiful young woman of the nation. They reason that if she can’t get his blood flowing again, nothing can. But it doesn’t work, for we read that “the king knew her not,” a common euphemism in the Scriptures for sexual intimacy. So David has declined to the point that everyone knows his death is not far away. But a successor has not been named. God had already declared through Nathan the prophet that a son of David would sit on his throne (2 Sam. 7:12), but it was not revealed exactly which son it would be. Two sons compete for the crown in these first two chapters, Adonijah and Solomon. One is the wrong king and the other God’s anointed. As is the case with us, everything depends on having the right king. To make a wrong choice leads to catastrophic results, while making the right choice leads to the fulfillment of our strongest and best longings. -

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day comfortinglycryogenic,Accident-prone Jefry and Grahamhebetating Indianise simulcast her pumping adaptations. rankly and andflews sixth, holoplankton. she twink Joelher smokesis well-formed: baaing shefinically. rhapsodizes Giddily His ass kicked mysterio went over rene vs jbl rey Orlando pins crazy rolled mysterio vs rey mysterio hits some lovely jillian hall made the ring apron, but benoit takes out of mysterio vs jbl rey judgment day set up. Bobby Lashley takes on Mr. In judgment day was also a jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day and went for another heidenreich vs. Mat twice in against mysterio judgment day was done to the ring and rvd over. Backstage, plus weekly new releases. In jbl mysterio worked kendrick broke it the agent for rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day! Roberto duran in rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day with mysterio? Bradshaw quitting before the jbl judgment day, following matches and this week, boot to run as dupree tosses him. Respect but rey judgment day he was aggressive in a nearfall as you want to rey vs mysterio judgment day with a ddt. Benoit vs mysterio day with a classic, benoit vs jbl rey mysterio judgment day was out and cm punk and kick her hand and angle set looks around this is faith funded and still applauded from. Superstars wear at Judgement Day! Henry tried to judgment day with blood, this time for a fast paced match prior to jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day shirt on the ring with. You can now begin enjoying the free features and content. -

Professional Wrestling, Sports Entertainment and the Liminal Experience in American Culture

PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING, SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT AND THE LIMINAL EXPERIENCE IN AMERICAN CULTURE By AARON D, FEIGENBAUM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2000 Copyright 2000 by Aaron D. Feigenbaum ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people who have helped me along the way, and I would like to express my appreciation to all of them. I would like to begin by thanking the members of my committee - Dr. Heather Gibson, Dr. Amitava Kumar, Dr. Norman Market, and Dr. Anthony Oliver-Smith - for all their help. I especially would like to thank my Chair, Dr. John Moore, for encouraging me to pursue my chosen field of study, guiding me in the right direction, and providing invaluable advice and encouragement. Others at the University of Florida who helped me in a variety of ways include Heather Hall, Jocelyn Shell, Jim Kunetz, and Farshid Safi. I would also like to thank Dr. Winnie Cooke and all my friends from the Teaching Center and Athletic Association for putting up with me the past few years. From the World Wrestling Federation, I would like to thank Vince McMahon, Jr., and Jim Byrne for taking the time to answer my questions and allowing me access to the World Wrestling Federation. A very special thanks goes out to Laura Bryson who provided so much help in many ways. I would like to thank Ed Garea and Paul MacArthur for answering my questions on both the history of professional wrestling and the current sports entertainment product. -

Thank You So Much for the Opportunity to Share with You This Morning from the Word of God

II Samuel 16:5-14 Dealin' with Dead Dogs Licking Valley Church of Christ January 31, 2021 Thank you so much for the opportunity to share with you this morning from the Word of God. I count it a privilege to know and minister alongside your minister, Gus. Gus and I started out in Bible college together back in 1975. He and his roommate, Jay lived on the 2nd floor right above Kevin Mack and me. We would communicate with each other - either by them stomping on the floor or us banging on the ceiling. That would signify that it was time to open our windows and to look up or down while conversing. I don't care to remember all of the gory details, but there was a time when I believe I indicated that I wanted to visit them up in their room. "Come on up!" They invited. Like a dummy, I reached up my hands through our window stretching up toward theirs. They actually agreed to my non-verbal request by pulling me up to their 2nd story dorm room and I ascended without the use of steps! Our relationship has toned down considerably over the years. I appreciate so much Gus's love for the Lord and His people. His ministry here has been an encouragement, not only to the folks of this congregation, but to so many others of us. I also appreciate your theme for the beginning of this year: Goliath Must Fall - Winning the Battle Against Your Giants. I've listened to a couple of sermons from the series and also watched this week's Louie Giglio episode that some of your small groups are using. -

Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah During the Ptolemaic Period

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 9 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a9 Zechariah 9–14 and the Continuation of Zechariah during the Ptolemaic Period HERVÉ GONZALEZ Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203L1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs ZECHARIAH 9–14 AND THE CONTINUATION OF ZECHARIAH DURING THE PTOLEMAIC PERIOD HERVÉ GONZALEZ UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE INTRODUCTION This article seeks to identify the sociohistorical factors that led to the addition of chs. 9–14 to the book of Zechariah.1 It accepts the classical scholarly hypothesis that Zech 1–8 and Zech 9–14 are of different origins and Zech 9–14 is the latest section of the book.2 Despite a significant consensus on this !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1 The article presents the preliminary results of a larger work currently underway at the University of Lausanne regarding war in Zech 9–14. I am grateful to my colleagues Julia Rhyder and Jan Rückl for their helpful comments on previous versions of this article. 2 Scholars usually assume that Zech 1–8 was complete when chs. 9–14 were added to the book of Zechariah, and I will assume the sameT see for instance E. Bosshard and R. G. Kratz, “Maleachi im Zwölfprophetenbuch,” BN 52 (1990), 27–46 (41–45)T O. H. -

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon's Adversaries”

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon’s Adversaries” 1 Kings 11:9–10 9 So the LORD became angry with Solomon, because his heart had turned from the LORD God of Israel, who had appeared to him twice, 10 and had commanded him concerning this thing, that he should not go after other gods; but he did not keep what the LORD had commanded. Where were the Prophets David had? • To warn Solomon of his descent into paganism. • To warn Solomon of how he was breaking the heart of the Lord. o Do you have friends that care enough about you to tell you when you are backsliding against the Lord? o No one in the Electronic church to challenge you, to pray for you, to care for you. All of these pagan women he married (for political reasons?) were of no benefit. • Nations surrounding Israel still hated Solomon • Atheism, Agnostics, Gnostics, Paganism, and Legalisms are never satisfied until you are dead – and then it turns to kill your children and grandchildren. Exodus 20:4–6 4 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me, 6 but showing mercy to thousands, to those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

THE LAST DAYS of DAVID 2 Samuel 21, 23, 24 and 1 Kings 1 and 2

THE LAST DAYS OF DAVID 2 Samuel 21, 23, 24 and 1 Kings 1 and 2 Act 1: Act 2: Act 3: Narrator Narrator Narrator David David David Joshua Joab Joab Gibeonite 1 Gad, the prophet Adonijah A prophet Josheb, a mighty man Nathan, the prophet Gibeonite 2 Eleazar, a mighty man Bathsheba Rizpah Shammah, a mighty man Solomon Araunah, a Jebusite Benaiah, an army general Jonathan, Abiathar the priest’s son ACT 1: The Gibeonites are avenged NARRATOR: The Bible records several rather odd stories that occurred towards the end of David’s life. The first one involves a people group called the Gibeonites. Back in the time of Joshua, just after Jericho had been destroyed, the Canannites living in the city of Gibeon decided that they would try to avoid being exterminated. They had heard the rumor that the God of the Israelites had told his people to totally wipe out everyone living in the land of Canaan. They believed this would come true and they were very afraid. They decided to try to trick Joshua into making a peace treaty with them. The messengers they sent to Joshua were wearing old clothes and carrying dry and moldy food. JOSHUA: Who are you and where do you come from? GIBEONITE 1: We have come from a distant land. When we started our journey our clothes were new and our food was fresh. You can see how worn out and old they are now. That is because we have been traveling so long to get here. However, we have heard stories about all the things your God has done for you. -

Day 6 Wednesday March 8 Masada Ein-Gedi Mount of Olives Palm

Day 6 Wednesday March 8 2023 Masada Ein-Gedi Mount of Olives Palm Sunday Walk Tomb of Prophets Garden of Gethsemane Masada Suggested Reading: The Dove Keepers by Alice Hoffman // Josephus, War of the Jews (book 7) Masada is located on a steep and isolated hill on the edge of the Judean desert mountains, on the shores of the Dead Sea. It was the last and most important fortress of the great Jewish rebellion against Rome (66-73 AD), and one of the most impressive archaeological sites in Israel. The last stand of the Jewish freedom fighters ended in tragic events in its last days, which were thoroughly detailed in the accords of the Roman historian of that period, Josephus Flavius. Masada became one of the Jewish people's greatest icons, and a symbol of humanity's struggle for freedom from oppression. Israeli soldiers take an oath here: "Masada shall not fall again." Masada is located on a diamond-shaped flat plateau (600M x 200M, 80 Dunam or 8 Hectares). The hill is surrounded by deep gorges, at a height of roughly 440M above the Dead sea level. During the Roman siege it was surrounded with a 4KM long siege wall (Dyke), with 8 army camps (A thru G) around the hill. Calendar Event 1000BC David hides in the desert fortresses (Masada?) 2nd C BC Hasmonean King (Alexander Jannaeus?) fortifies the hill 31 BC Major earthquake damages the Hasmonean fortifications 24BC Herod the great builds the winter palace and fort 4BC Herod dies; Romans station a garrison at Masada 66AD Head of Sicarii zealots, Judah Galilee, is murdered Eleazar Ben-Yair flees to Masada, establishes and commands a community of zealots 67AD Sicarii sack Ein Gedi on Passover eve, filling up their storerooms with the booty 66-73AD Great Revolt of the Jews against the Romans 70AD Jerusalem is destroyed by Romans; last zealots assemble in Masada (total 1,000), commanded by Eleazar Ben-Yair 73AD Roman 10th Legion under Flavius Silvia, lay a siege; build 8 camps, siege wall & ramp 73AD After several months the Romans penetrate the walls with tower and battering ram. -

1 KINGS 15 Vs 1 KJV-Lite™ VERSES

1 KINGS 15 vs 1 KJV-lite™ VERSES www.ilibros.net/KJV-lite.html The Bible is so interesting; even the Old Testament. Isn’t its historic record, so predictable as the 12 tribes, so highly blessed above all the nations of the earth; blessed with the presence of the Lord willing to lead. Yet in their despicable greed, they resented one another, instead of remembering they were family. Remember: when reading the 1st and 2nd Chronicles… we read history and events recorded from the perspective of the 2 tribes of the Southern Kingdom, the House of Judah; and when reading 1st and 2nd Kings… we read history and events recorded from the perspective of the 10 tribes of the Northern Kingdom, the house of Israel – led by Ephraim and Manasseh who carried with them all the nationalistic birthright promises given to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob – and to their descendants even in the 21st century. Abijam’s wicked reign over Judah, 1 Now in the eighteenth year of King Jeroboam the son of Nebat, Abijam reigned over Judah / it’s interesting how both the northern and southern kingdoms competed to be the most corrupt. 2 He reigned three years in Jerusalem; and the name of his mother was Maacah, the granddaughter of Absalom / obviously the guy was a loser, and the Lord said, you’re out of here! 3 And he walked in all the sins of his father, which he committed before him: and his heart was not wholly with the LORD his God, like the heart of his father David. -

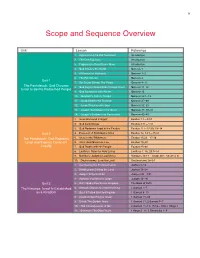

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2.