Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dogme95, Lars Von Trier, and the Cinema of Subversion?

40 Reconsidering The Idiots TIM WALTERS Reconsidering The Idiots: Dogme95, Lars von Trier, and the Cinema of Subversion? Art is not a mirror to reflect reality, but a hammer when viewed in light of its counter-hegemonic aspira- with which to shape it. —Bertolt Brecht tions. As a finished product, The Idiots is an uneasy synthesis Sheds are bourgeois crap. —Stoffer, The Idiots that attempts to locate an elusive sense of the “real” in late capitalist (film) culture, one in which the spassing (or sustained faking of mental disability) on the part of sing Lars von Trier’s controversial The the film’s characters is ideologically reflected by the Idiots (1998) as a starting point, I intend to seemingly amateurish precepts of its construction. In examine the compelling ways in which the this respect, The Idiots is unlike the other Dogme films. U infamous Dogme95 manifesto aims to ad- Although these works all tend to be technically quite dress and correct the failings of contemporary film. The oppositional or at least adventurous, they nevertheless Idiots is a remarkable and provocative materialist cri- maintain a rigid split between form and content and tique of modern culture in its own right, but its mean- therefore offer very little sustained political critique of ing is significantly complicated by its centrality to the the ideology of mainstream society or cinema. My otherwise celebrated output of the Dogme95 move- argument is that The Idiots is the only recent counter- ment. It received virtually none of the critical acclaim, hegemonic film work that is demonstrably radical both financial success, or festival awards garnered by the other in its form and its content and, moreover, in its brilliant major Dogme films such as Mifune (1999) and The Cel- and playful deconstruction of these categories. -

Lars Von Trier: the Impossibility of the Good As a Work

TYLER TRITTEN Alberts-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg LARS VON TRIER: THE IMPOSSIBILITY OF THE GOOD AS A WORK any philosophers have paid a great deal of attention to Plato’s assertion in the sixth Book of The Republic that ‘the Good is not essence, but far Mexcee ds essence in dignity and power’1. Now, one can only understand a philosopher by meeting her where she begins. F.W.J. von Schelling once wrote: ‘If one wants to honor a philosopher, then one must grasp him here, in his fundamental thought, where he has not yet gone on to the consequences. … The true thought of a philosopher is precisely his fundamental thought from which he proceeds’2 What is true of the philosopher is also true of the film director, who often becomes entranced and traumatized by one image3 that never releases its grip. This article will show that the one constant pervading the films of Danish filmmaker Lars von Trier is the impossibility of the Good as a work, i.e. as a ‘good work’ accomplished by the autonomy of the agent. In short, this work aims to show that von Trier criticizes any conception of the Good as a work wrought by and appropriable by an agent, and instead offers an account of the Good as something that can only occur through self-effacing, self-sacrificial patients who become transparencies for the operativity of the Good itself Von Trier regularly depicts characters - at least when they are men - who attempt to enact the Good as a work of their own and yet find themselves unable to do so, at least not by means of their own agency. -

Constraints in Film Making Processes Offer an Exercise to the Imagination - a Pleading Based on Experiences from Denmark

Constraints in Film Making Processes Offer an Exercise to the Imagination - A Pleading Based on Experiences from Denmark Heidi Philipsen Ph.D., Assistant Professor University of Southern Denmark Email: [email protected] Abstract What does the use of constraints offer filmmakers? A screenwriter from The National Film School of Denmark suggests: “I love constraints [..]. I think that’s a great relief, because it offers an exercise to your imagination” (Philipsen 2005: 211). This article hopes to illuminate methods for fostering creativity based on two case studies from The National Film School of Denmark and The Video Clip Cup 2007. In scrutinising these studies I intend to describe what seems to best facilitate flow experiences in film making, and I reflect upon what "individual, team, and institutional scaffolding" can offer a creative film making process as educational techniques. I will outline elements essential to getting into the flow of the film process through the help of constraints and collaboration. Moreover, I focus on the consequences of authorial action. And finally my findings are applied to the work of two professional Danish film makers, Lars von Trier and Jørgen Leth. Keywords: Media, creativity, learning, scaffolding, National Film School of Denmark Introduction I would like filmmakers interested in thinking "outside the box" to recognize that they can benefit from being placed "inside a box." In others words, to work with the help of the didactic tool "scaffolding," which in short is defined as support through constraints applied at different levels (Wood, Bruner and Ross 1976). The scaffolding employed at The National Film School of Denmark helps the students to cope with the pressure of creating film, find inspiration, and attain a flow experience (Csikszentmihaly 1996). -

GERMAN CINEMA in the AGE of NEOLIBERALISM Hester Baer German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION GERMAN CINEMA IN THE AGE OF NEOLIBERALISM hester baer German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism Hester Baer Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by a grant from the University of Maryland, College Park. Cover illustration: Patrick Bauchau & Crew in The State of Things (Portugal, USA, Germany 1981/82) by Wim Wenders © Wim Wenders Stiftung 2015 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 733 4 e-isbn 978 90 4855 195 8 doi 10.5117/9789463727334 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) H. Baer / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 Introduction: Making Neoliberalism Visible 11 1. German Cinema and the Neoliberal Turn : The End of the National-Cultural Film Project 43 2. Producing German Cinema for the World : Global Blockbusters from Location Germany 77 3. From Everyday Life to the Crisis Ordinary : Films of Ordinary Life and the Resonance of DEFA 129 4. Future Feminism : Political Filmmaking and the Resonance of the West German Feminist Film Movement 157 5. -

Patrick Bauchau Films and Movies (Filmography) List

Patrick Bauchau Movies List (Filmography) Clear and Present Danger https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/clear-and-present-danger-1392442/actors The Five Obstructions https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-five-obstructions-2632905/actors Chrysalis https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/chrysalis-1088433/actors Cross https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cross-3003757/actors https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/day-5%3A-1%3A00-pm%C2%A0--2%3A00-pm- Day 5: 1:00 pm - 2:00 pm 52263123/actors House https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/house-23558/actors Vampires: The Turning https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vampires%3A-the-turning-3062937/actors Kane & Abel https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kane-%26-abel-93882478/actors https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/la-possibilit%C3%A9-d%27une-%C3%AEle- La Possibilité d'une île 3211832/actors Twin Falls Idaho https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twin-falls-idaho-3232815/actors Choose Me https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/choose-me-4128503/actors The Public Woman https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-public-woman-1220035/actors Dario Argento's World of https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/dario-argento%27s-world-of-horror-515104/actors Horror https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/104906349/actors The Music Teacher https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-music-teacher-1405508/actors https://www.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/day-5%3A-2%3A00-pm%C2%A0--3%3A00-pm- Day 5: 2:00 pm - 3:00 pm 52263124/actors -

German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism, Hester Baer.Pdf

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION GERMAN CINEMA IN THE AGE OF NEOLIBERALISM hester baer This content downloaded from 128.8.44.222 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 13:28:12 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism This content downloaded from 128.8.44.222 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 13:28:12 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms This content downloaded from 128.8.44.222 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 13:28:12 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms German Cinema in the Age of Neoliberalism Hester Baer Amsterdam University Press This content downloaded from 128.8.44.222 on Wed, 14 Jul 2021 13:28:12 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms The publication of this book is made possible by a grant from the University of Maryland, College Park. Cover illustration: Patrick Bauchau & Crew in The State of Things (Portugal, USA, Germany 1981/82) by Wim Wenders © Wim Wenders Stiftung 2015 Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 733 4 e-isbn 978 90 4855 195 8 doi 10.5117/9789463727334 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) H. Baer / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Management Et Représentation Enquête Sur Les Représentations Du Management Dans Le Cinéma Français, 1895-2005

UNIVERSITE DE NANTES Institut d’Economie et de Management de Nantes – IAE 2008 THESE pour l’obtention du grade de docteur en sciences de gestion présentée et soutenue publiquement par Eve LAMENDOUR le 8 septembre 2008 Management et représentation Enquête sur les représentations du management dans le cinéma français, 1895-2005 Volume 2 : Annexes JURY DIRECTEURS DE RECHERCHE Yannick LEMARCHAND, Professeur à l’Université de Nantes Patrick FRIDENSON, Directeur d'études à l’EHESS RAPPORTEURS Anne PEZET, Professeur à l’Université Paris-Dauphine Pierre SORLIN, Professeur émérite à l’Université Paris III SUFFRAGANTS Mathieu DETCHESSAHAR, Professeur à l’Université de Nantes Hervé LAROCHE, Professeur à l’ESCP-EAP Béatrice de PASTRE, Directrice des collections aux Archives Françaises du Film, CNC ANNEXES Table des annexes 1. Droit d’auteur 3 2. Glossaires 5 a. Glossaire des notions managériales 5 b. Vocabulaire de l’analyse filmique 11 c. Abréviations et termes de référence de la description du corpus 15 3. Filmographies 19 a. Sources d’accès aux films 19 b. Corpus pratique 20 c. Corpus théorique : liste chronologique 35 d. Corpus théorique : fiches des films 43 e. Corpus de comparaison 167 La représentation de l’entreprise et du management dans le cinéma américain 167 Chronologie de films susceptibles d’éclairer la question managériale 168 4. Tableaux 174 a. Chapitre 3 174 Tableau récapitulatif des concessionnaires et agents commerciaux Lumière b. Chapitre 4 175 Sources d’information concernant les films « grévistes » c. Chapitre 10 176 Sources d’information concernant les slogans des cabinets de conseil d. Conclusion Partie IV 177 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, 1936 – 1975 177 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, 1982 – 2000 178 Le poids du management dans la population active en France, les années 2000 179 Evolution des métiers à composante managériale, 1982 – 2006 180 5. -

A Hearse Heading Home

WELCOME “I would like to invite you for a tiny glimpse behind the curtain, a glimpse into the dark world of my imagination: into the nature of my fears, into the nature of Antichrist.” Lars von Trier PITCH A grieving couple retreat to ’Eden’, their isolated cabin in the woods, where they hope to repair their broken hearts and troubled marriage. But nature takes its course and things go from bad to worse… DIRECTOR’S CONFESSION Two years ago, I suffered from depression. It was a new experience for me. Everything, no matter what, seemed unimportant, trivial. I couldn’t work. Six months later, just as an exercise, I wrote a script. It was a kind of therapy, but also a search, a test to see if I would ever make another film. The script was finished and filmed without much enthusiasm, made as it was us- ing about half of my physical and intellectual capacity. The work on the script did not follow my usual modus operandi. Scenes were added for no reason. Images were composed free of logic or dramatic thinking. They often came from dreams I was having at the time, or dreams I’d had earlier in my life. Once again, the subject was ”Nature,” but in a different and more direct way than before. In a more personal way. The film does not contain any specific moral code and only has what some might call ‘the bare necessities’ in the way of a plot. I read Strindberg when I was young. I read with enthusiasm the things he wrote before he went to Paris to become an alchemist and during his stay there .. -

The Experimental Contribution of the Five Obstructions

Organizational Aesthetics 9(2): 42-61 Ó The Author(s) 2020 www.organizationalaesthetics.org Organising the illumination of the filmmaking process: The experimental contribution of The Five Obstructions. Matteo Ciccognani School of Business. University of Leicester. Abstract The paper analyses The Five Obstructions (Von Trier, Leth, 2003) a productionist metafilm that illuminates film production organisational process. A productionist metafilm is a reflexive work which expands on the processual dimension of filmmaking to the extent that the frontstage of production might be said to coincide, or tend to coincide, with its own backstage. In such a way, it provides a favourable observation spot of the filmmaking process over some of its material components of production and the role of authors and practitioners. Specifically, The Five Obstructions provides an organisational model of filmmaking which exceeds the canonical representations of mainstream cinema – but that also differs from other metacinematic examples - for its unique capability to frame the exhibition of the productive process as the main agent of the representation in its constitutive material aspects. Drawing on scholarship focusing on organisational performance, critical management studies and film studies, this article attempts to investigate the extent to which this audiovisual product can provide a contribution which exceeds the limits established by the domain of filmmaking. It is questioned whether it can also generate a deeper understanding of diverse work environments dynamics and promote organisational change. The Five Obstructions operates in this direction by inviting the participants to role-play, to exhibit their own role within the filmmaking process. In particular, this film focuses on issues related to co- performed production, leadership, self-management and disorganisation. -

Nymphomaniac Volume I (Long Version) Ausser Konkurrenz

WETTBEWERB NYMPHOMANIAC VOLUME I (LONG VERSION) AUSSER KONKURRENZ Lars von Trier In einer Gasse vor seinem Wohnhaus liest der alternde Junggeselle Se- Dänemark/Deutschland/Frankreich/ ligman eine blutüberströmte junge Frau auf und nimmt sie mit zu sich. Belgien/Schweden 2013 Dort erzählt ihm Joe aus ihrem Leben, von ihren Erfahrungen mit Män- 145 Min. · DCP · Farbe nern und der unstillbaren Sucht nach Sex. Über die Physiologie des weiblichen Körpers haben sie die Bücher ihres Vaters aufgeklärt, der Regie, Buch Lars von Trier Kamera Manuel Alberto Claro Arzt ist. Noch nicht erwachsen, geht sie gemeinsam mit einer Freundin Schnitt Molly Malene Stensgaard auf Sextour, verführt Männer in Wohnungen, Zugabteilen, Kneipen, Musik Rammstein Büros. Und findet in Jerôme, von dem sie ein Kind hat, eine Konstante Sejersen Casper Foto: Sound Design Kristian Selin, in ihrem Dasein. Doch das Glück ist zerbrechlich. Eidnes Andersen Geboren 1956 in Kopenhagen. Von Trier ist Nach ANTICHRIST (2009) und MELANCHOLIA (2011) präsentiert Lars Ton Andreas Hildebrandt einer der Gründer der Dogma-95-Bewegung von Trier mit NYMPHOMANIAC den Abschluss seines „Triptychons der Production Design Simone Grau Roney und der dänischen Produktionsfirma Zentropa. Depression“. Zugleich reflektiert er mit der Beichte einer Frau, die mit Kostüm Manon Rasmussen Er studierte Filmwissenschaften an der der eigenen Geschichte ringt, über die Suche nach Sinn und Balan- Maske Dennis Knudsen Universität Kopenhagen und Regie an der Casting Des Hamilton dänischen Filmhochschule. Sein Kinodebüt ce im Leben. Ein zweiteiliger filmischer Entwicklungsroman von Er- regung und Verzweiflung, Lust und Schmerz, mit historischen und li- Spezialeffekte Peter Horth feierte er 1984 mit THE ELEMENT OF CRIME. -

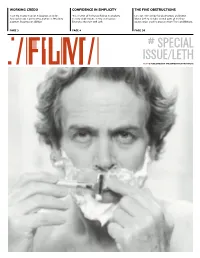

Special Issue/Leth

WORKING CREDO CONFIDENCE IN SIMPLICITY THE FIVE OBSTRUCTIONS “I put the images in order. It becomes an order. ”It’s a matter of having confidence in simplicity, Lars von Trier set up five obstructions challenging And each image is put next to another, is fitted into in every single minute, in time as it passes.” Jørgen Leth to ‘remake’ central parts of his filmic a pattern. Becomes an addition.” Extensive interview with Leth. oeuvre under creative pressure from Trier’s prohibitions. PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 30 # SPECIAL l1l ISSUE/LETH FILM IS PUBLISHED BY THE DANISH FILM INSTITUTE FILM#SPECIAL ISSUE / LETH / PAGE 2 3 WORKING CREDO DANISH FILM INSTITUTE Gothersgade 55 Jørgen Leth l1l DK-1123 Copenhagen K T +45 3374 3400 SPECIAL ISSUE / LETH W www.dfi.dk 4 INTERVIEW WITH LETH INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS WORKING CREDO CONFIDENCE IN SIMPLICITY THE FIVE OBSTRUCTIONS Excerpt from Hjort & Bondebjerg’s ‘The Danish Directors “I put the images in order. It becomes an order. ”It’s a matter of having confidence in simplicity, Lars von Trier set up five obstructions challenging And each image is put next to another, is fitted into in every single minute, in time as it passes.” Jørgen Leth to ‘remake’ central parts of his filmic a pattern. Becomes an addition.” Extensive interview with Leth. oeuvre under creative pressure from Trier’s prohibitions. SHORTS & DOCUMENTARIES: PAGE 3 PAGE 4 PAGE 30 – Dialogues on a Contemporary National Cinema’ # SPECIAL Anne Marie Kürstein l1l ISSUE/LETH [email protected] FILM IS PUBLISHED BY THE DANISH FILM INSTITUTE Annette Lønvang [email protected] 22 NOTES ON LOVE FEATURES: + HOLDING YOUR HANDS FIRMLY Sanne Pedersen [email protected] Bronislaw Malinowski + Jørgen Leth PUBLISHED BY: Danish Film Institute 24 THE EROTIC HUMAN In pre-production EDITOR: Agnete Dorph Stjernfelt TRANSLATION: 26 THE MAGIC OF THE FILM REEL Front page: From Notes on Love. -

PLAYING the WAVES JAN SIMONS Critics Praised the Directors’ Low Budgets and Team Work, and Film Fans Appreciated the Bold Look at Contemporary FILM FILM Life

Dogma 95 has been hailed as the European renewal of independent and innovative film-making, in the tradition of Italian neo-realism and the French nouvelle vague. SIMONS JAN THE WAVES PLAYING Critics praised the directors’ low budgets and team work, and film fans appreciated the bold look at contemporary FILM FILM life. Lars von Trier – the movement’s founder and guiding spirit – however, also pursued another agenda. His CULTURE CULTURE approach to filmmaking takes cinema well beyond the IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION traditional confines of film aesthetics and radically trans- poses the practice of film making and film itself right into what has become the paramount genre of new media: games and gaming. Dogma 95, this book argues, is not an exceptional phase in Von Trier’s career – as it was for PLAYINGPLAYING his co-founders – but the most explicit formulation of a cinematic games aesthetics that has guided the concep- tion and production of all of his films. Even the launching of Dogma 95 and the infamous THETHE WAVESWAVES Dogma Manifesto were conceived as a game, and ever since Von Trier has redefined the practice of film making as a rule bound activity, bringing forms and structures of games to bear on his films, and draw- ing some surprising lessons from economic and evolutionary game theory. This groundbreaking study argues that Von Trier’s films can be better understood from the per- spective of games studies and game theory than from the point of view of traditional film theory and film aesthetics. Jan Simons is Associate Professor of New Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam.