Portfolio Management Plan: Northern Intersecting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death Register 2008

BURIAL RECORDS 12/01/2012 Cust ID Surname Name Christian Name Age Yrs Date of Death Cemetery Portion Date of Burial Row Lot 3670 LUCY 25 MISSION 3677 MULGA BILLY 37 1 OCTOBER 1902 TATALA STATION 3675 MARY ANN 70 11 NOVEMBER 1909 MISSION 3672 MARY ANN 58 13 JULY 1919 DENAWIN 3676 MARY ANN 58 13 JULY 1919 DENAWIN 3666 DICK 47 14 JULY 1919 DENAWIN STATION 3669 JIMMY 55 15 MAY 1918 WEILMORINGLE 3662 "YORKY" 55 15 NOVEMBER 1863 "GURRAWARRA" 3680 OLD JACK 45 18 JANUARY 1882 BREWARRINA 3673 MARY ANN 1898 3682 SALLY 40 22 MARCH 1890 BREWARRINA ANGLICAN 23 MARCH 1890 3667 GLADYS MURIEL 3/12 25 JANUARY 1897 BREWARRINA 3668 JACK 70 26 APRIL 1896 TATALA 3678 NANNY 72 26 FEBRUARY 189 BREWARRINA 3683 WILLIAM ABOUT 70 27 APRIL 1889 TALAWANTA 3665 BIDDY 60 27 OCTOBER 1895 MISSION 3664 ANTHONY 49 (NOT KN 28 FEBRUARY 1877 BREWARRINA ANGLICAN 1 MARCH 1877 559 BABY 1 10/12 3(30) MAY 1878 BREWARRINA CATHOLIC 2 JUNE 1878 AO 18 3674 MARY ANN 70 30 MARCH 1898 MISSION 3681 RALPH 25 30 NOVEMBER 1896 MISSION BREWARRINA 3671 MARY 35 30 OCTOBER 1923 BREWARRINA 3679 NANNY 38 6 AUGUST 1896 URIE POINT 3663 ALECK 36 8 MAY 1903 WEILMORINGLE 749 ABBOTT JOHN THOMAS 1 11 SEPTEMBER 1881 GOLGOLGON 750 ADAMS THOMAS 77 (11 NOVEMBER) 1896 BREWARRINA CATHOLIC 11 OCTOBER 1896 635 (AGOSTINE JOHN PAUL (POLO) 30 24 NOVEMBER 1923 BREWARRINA CATHOLIC 25 NOVEMBER 1923 GO 11 751 AH SAM 49 27 AUGUST 1881 BREWARRINA 752 AH SAM 35 9 OCTOBER 1893 WEILMORINGLE AH BOW JOHNNIE 58 1 MARCH 1918 GOODOOGA 754 AH CHING (AH CHIN) (L MARGARET 27 10 FEBRUARY 1909 BREWARRINA CATHOLIC 10 FEBRUARY 1909 -

Inglewood Shire Handbook

INGLEWOOD SHIRE HANDBOOK An Inventory of the Agricultural Resources and Production of Inglewood Shire, Queensland Queensland Department of Primary Industries November 1977 Queensland Government Technical Report This report is a scanned copy and some detail may be illegible or lost. Before acting on any information, readers are strongly advised to ensure that numerals, percentages and details are correct. This report is intended to provide information only on the subject under review. There are limitations inherent in land resource studies, such as accuracy in relation to map scale and assumptions regarding socio-economic factors for land evaluation. Before acting on the information conveyed in this report, readers should ensure that they have received adequate professional information and advice specific to their enquiry. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report neither the Queensland Government nor its officers or staff accepts any responsibility for any loss or damage that may result from any inaccuracy or omission in the information contained herein. © State of Queensland 1977 For information about this report contact [email protected] INGLEWOOD SHIRE HANDBOOK An Inventory of the Agricultural Resources and Production of Ingle wood Shire, Queensland Compiled by: G. H. Malcolmson, District Adviser, Inglewood. Edited by: P. L. Lloyd, Extenson Officer, Brisbane. Published by: Queensland Department of Primary Industries. November 1977 FOREWORD The Shire Handbook was conceived in the mid-1960s. A limited number of a series was printed for use by officers of the Department of Primary Industries to assist them in their planning of research and extension programmes. The Handbooks created wide interest and, in response to public demand, it was decided to publish progressively a new updated series. -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

Upper Condamine Region

Upper Talking fish Making connections with the rivers of the Murray-Darling Basin Authors ZaferSarac,HamishSewell,GregRingwood,LizBakerandScottNichols The rivers of the Murray-Darling River Basin Citation:Sarac,Z.,Sewell,H.,Ringwood,G.Baker,E.andNichols,S.(2012)Upper TheriversandcreeksoftheMurrayͲDarlingBasinflowthroughQueensland,NewSouth Condamine:TalkingfishͲmakingconnectionswiththeriversoftheMurrayͲ Wales,theAustralianCapitalTerritory,VictoriaandSouthAustralia.The77000kmof DarlingBasin,MurrayͲDarlingBasinAuthority,Canberra. waterwaysthatmakeuptheBasinlink23catchmentsoveranareaof1millionkm2. Projectsteeringcommittee TerryKorodaj(MDBA),CameronLay(NSWDPI),ZaferSarac(QldDEEDI),Adrian Eachriverhasitsowncharacteryetthesewaters,thefish,theplants,andthepeoplethat Wells(MDBACommunityStakeholderTaskforce),PeterJackson(MDBANative relyonthemarealldifferent. FishStrategyadvisor),FernHames(VicDSE)andJonathanMcPhail(PIRSA). Thebookletsinthisseriestellthestoriesofhowtherivers,fishandfishinghavechanged. ProjectTeam ScottNichols,CameronLay,CraigCopeland,LizBaker(NSWDPI);JodiFrawley, Themainstoriesinthesebookletsarewrittenfromoralhistoryinterviewsconductedwith HeatherGoodall(UTS);ZaferSarac,GregRingwood(QldDEEDI);HamishSewell localfishersin2010Ͳ11,andrelateindividuals’memoriesofhowtheirlocalplaceshave (TheStoryProject);PhilDuncan(NgnuluConsulting);TerryKorodaj(MDBA); changed.ThesebookletsshowcasethreewaysofknowingtheCondamineRiver:personal FernHames,PamClunie,SteveSaddlier(VicDSE);JonathanMcPhail, VirginiaSimpson(PIRSA);WillTrueman(researcher). -

District and Pioneers Ofthe Darling Downs

His EXCI+,t,i,FNCY S[R MATTI{FvC NATHAN, P.C., G.C.M.G. Governor of Queensland the Earlyhs1orvof Marwick Districtand Pioneers ofthe DarlingDowns. IF This is a blank page CONTENTS PAGE The Early History of Warwick District and Pioneers of the Darling Downs ... ... ... ... 1 Preface ... ... ... .. ... 2 The. Garden of Australia -Allan Cunningham's Darling Downs- Physical Features ... ... ... 3 Climate and Scenery .. ... ... ... ... 4 Its Discovery ... ... ... ... ... 5 Ernest Elphinstone Dalrymple ... ... 7 Formation of First Party ... ... ... 8 Settlement of the Darling Downs ... ... ... 9 The Aborigines ... ... ... ... 13 South 'roolburra, The Spanish Merino Sheep ... 15 Captain John Macarthur ... ... ... ... 16 South Toolburra's Histoiy (continued ) ... ... 17 Eton Vale ... ... ... ... 20 Canning Downs ... ... ... ... ... 22 Introduction of Llamas ... ... ... 29 Lord John' s Swamp (Canning Downs ) ... ... ... 30 North Talgai ... ... ... ... 31 Rosenthal ... ... ... ... ... 35 Gladfield, Maryvale ... ... ... ... 39 Gooruburra ... ... ... ... 41 Canal Creek ... ... ... ... ... 42 Glengallan ... ... ... ... ... 43 Pure Bred Durhams ... ... ... ... ... 46 Clifton, Acacia Creek ... ... ... ... 47 Ellangowan , Tummaville ... 48 Westbrook, Stonehenge Station ... ... ... ... 49 Yandilla , Warroo ... ... ... ... ... 50 Glenelg ... ... .,, ... 51 Pilton , The First Road between Brisbane and Darling Downs , 52 Another Practical Road via Spicer' s Gap ,.. 53 Lands Department and Police Department ... ... ... 56 Hard Times ... ... ... 58 Law and Order- -

2019 Citizens' Inquiry Into the Health of the Barka/Darling River And

Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry into the Health of the Barka/Darling River and Menindee Lakes REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 30 SEPTEMBER 2020 Michelle Maloney, Gill Boehringer, Gwynn MacCarrick, Manav Satija, Mary Graham and Ross Williams Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights an initiative of the Australian Earth Laws Alliance Michelle Maloney • Gill Boehringer Gwynn MacCarrick • Manav Satija Report Editor Michelle Maloney Mary Graham • Ross Williams Layout, Cover Design and uncredited photos: James K. Lee Cover image: Wilcannia Bridge over the Barka / Darling River. 24 March 2019. 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry © 2020 Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT) into the Health of the Barka / Darling River All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review), no part of this report may be reproduced, and Menindee Lakes stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written permission. The Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT) is an initiative of the Australian Report and Earth Laws Alliance. All inquiries should be directed to the Australian Earth Laws Alliance (AELA). Recommendations https://www.earthlaws.org.au [email protected] Suggested citation: Maloney, M., Boehringer, G., MacCarrick, G., Satija, M., Graham, M. & Williams, R. (2020) 2019 Citizens’ Inquiry into the Health of the Barka / Darling River and Menindee Lakes: Report and Recommendations. Australian Peoples’ Tribunal for Community and Nature’s Rights (APT). -

Portfolio Management Plan Northern Unregulated Rivers 2017–18

Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan Northern Unregulated Rivers 2017–18 Commonwealth Environmental Water Office Front cover image credit: Darling River at Toorale. Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. Back cover image credit: Monitoring and research at Toorale. Photo by Commonwealth Environmental Water Office. The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office respectfully acknowledges the traditional owners, their Elders past and present, their Nations of the Murray-Darling Basin, and their cultural, social, environmental, spiritual and economic connection to their lands and waters. © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2017. Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Northern Unregulated Rivers 2017–18 is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This report should be attributed as ‘Commonwealth Environmental Water Portfolio Management Plan: Northern Unregulated Rivers 2017–18, Commonwealth of Australia, 2017’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright’ noting the third party. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Energy. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

ANPS Data Report No 6

DARLING DOWNS Natural Features and Pastoral Runs 1827 to 1859 ANPS DATA REPORT No. 6 2017 DARLING DOWNS Natural Features and Pastoral Runs 1827 to 1859 Dale Lehner ANPS DATA REPORT No. 6 2017 ANPS Data Reports ISSN 2206-186X (Online) General Editor: David Blair Also in this series: ANPS Data Report 1 Joshua Nash: ‘Norfolk Island’ ANPS Data Report 2 Joshua Nash: ‘Dudley Peninsula’ ANPS Data Report 3 Hornsby Shire Historical Society: ‘Hornsby Shire 1886-1906’ (in preparation) ANPS Data Report 4 Lesley Brooker: ‘Placenames of Western Australia from 19th Century Exploration ANPS Data Report 5 David Blair: ‘Ocean Beach Names: Newcastle-Sydney-Wollongong’ Fences on the Darling Downs, Queensland (photo: DavidMarch, Wikimedia Commons) Published for the Australian National Placenames Survey This online edition: September 2019 [first published 2017, from research data of 2002] Australian National Placenames Survey © 2019 Published by Placenames Australia (Inc.) PO Box 5160 South Turramurra NSW 2074 CONTENTS 1.0 AN ANALYSIS OF DARLING DOWNS PLACENAMES 1827 – 1859 ............... 1 1.1 Sample one: Pastoral run names, 1843 – 1859 ............................................................. 1 1.1.1 Summary table of sample one ................................................................................. 2 1.2 Sample two: Names for natural features, 1837-1859 ................................................. 4 1.2.1 Summary tables of sample two ............................................................................... 4 1.3 Comments on the -

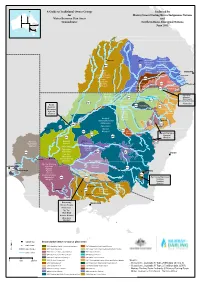

Guide to Traditional Owner Groups for WRP Areas Combined Maps

A Guide to Traditional Owner Groups Endorsed by for Murray Lower Darling Rivers Indigenous Nations Water Resource Plan Areas and Groundwater Northern Basin Aboriginal Nations June 2015 Nivelle River r e v i R e l a v i Nive River r e M M a Beechal Creek Langlo River r a n o a R i !( v Gunggari e Ward River Charleville r Roma Bigambul !( Guwamu/Kooma Barunggam Jarowair k e Bidjara GW22 e Kambuwal r GW21 «¬ C Euahlayi Mandandanji a «¬ Moola Creek l Gomeroi/Kamilaroi a l l Murrawarri Oa a k Bidjara Giabel ey Cre g ek n Wakka Wakka BRISBANE Budjiti u Githabul )" M !( Guwamu/Kooma Toowoomba k iver e nie R e oo Kings Creek Gunggari/Kungarri r M GW20 Hodgson Creek C Dalrymple Creek Kunja e !( ¬ n « i St George Mandandanji b e Bigambul Emu Creek N er Bigambul ir River GW19 Mardigan iv We Githabul R «¬ a e Goondiwindi Murr warri n Gomeroi/Kamilaroi !( Gomeroi/Kamilaroi n W lo a GW18 Kambuwal a B Mandandanji r r ¬ e « r g Rive o oa r R lg ive r i Barkindji u R e v C ie iv Bigambul e irr R r r n Bigambul B ive a Kamilleroi R rr GW13 Mehi River Githabul a a !( G Budjiti r N a ¬ w Kambuwal h « k GW15 y Euahlayi o Guwamu/Kooma d Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Paroo River B Barwon River «¬ ir GW13 Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ri Bigambul Kambuwal ver Kwiambul Budjiti «¬ Kunja Githabul !( GW14 Kamilleroi Euahlayi Bourke Kwiambul «¬ GW17 Kambuwal Namo iver Narrabri ¬ i R « Murrawarri Maljangapa !( Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Ngemba Murrawarri Kwiambul Wailwan Ngarabal Ngarabal B Ngemba o g C a Wailwan Talyawalka Creek a n s Barkindji R !( t l Peel River M e i Wiradjuri v r Tamworth Gomeroi/Kamilaro -

Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001

Improving the understanding of water availability and use by vegetation of the Lower- Balonne Floodplain. Final research report for the project ‘Watering requirements of floodplain vegetation asset species of the Northern Murray-Darling Basin’. December 2017 1 Prepared by Water Planning Ecology, Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 Department of Natural Resources and Mines 203 Tor St Toowoomba QLD 4350 © The State of Queensland (Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation and Department of Natural Resources and Mines) 2017 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI/DNRM, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation and Department of Natural Resources and Mines as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en ISBN 978-1-925075-01-4 Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. -

Condamine River: Flood Intelligence Review Draft for Public Review

CONDAMINE RIVER: FLOOD INTELLIGENCE REVIEW DRAFT FOR PUBLIC REVIEW SEPTEMBER 2017 Toowoomba Regional Council PROJECT DETAILS Report Title Condamine River: Flood Intelligence Review Draft for Public Review Client Toowoomba Regional Council WMS Project Manager Blake Boulton Job Number Document Name 0022_Condamine_FI_Review_Draft.docx DOCUMENT STATUS Revision Doc Report Distributed Report Reviewer Number Type Author to Date 00 Draft TM BB TRC 13/09/2017 Draft for 01 Public TM BB Public 22/09/2017 Review REVISION STATUS Revision Number Description 00 Draft Report 01 Draft Report for Public Review COPYRIGHT AND NON-DISCLOSURE NOTICE The contents and layout of this report are subject to copyright owned by Water Modelling Solutions Pty Ltd (WMS). The report may not be copied or used without our prior written consent for any purpose other than the purpose indicated in this report. The sole purpose of this report and the associated services performed by WMS is to provide the information required in accordance with the scope of services set out in the contract between WMS and the Client. That scope of services was defined by the requests of the Client, by the time and budgetary constraints imposed by the Client, and by the availability of data and other relevant information. In preparing this report, WMS has assumed that all data, reports and any other information provided to us by the Client, on behalf of the Client, or by third parties is complete and accurate, unless stated otherwise. 0022_Condamine_FI_Review_Draft.docx | 22 September 2017 | Page i Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Project Background and Objectives ................................................................................. -

Summary of Weather and Flood Events

1.Summary.of.weather. and.flood.events What follows is an overview of the weather events leading up to and during the 2010/2011 floods with a summary of their effects across the state. It is not intended as an exhaustive account. 1.1.Summary.of.weather.leading.to. 1 2010/2011.flood.events The Queensland wet season extends from October to April, with the initial monsoonal onset usually occurring in late December. The 2010/2011 wet season was different. In June 2010 the Australian Bureau of Meteorology warned that a La Niña event was likely to occur before the end of the year.1 The La Niña change has historically brought above average rainfall to most of Australia and an increased risk of tropical cyclone events for northern Australia. Previous La Niña effects had been associated with flooding in eastern Australia, including the large scale and devastating floods which occurred in 1955 and 1973/1974.2 As predicted, a strong La Niña event took place in the Pacific Ocean in late 2010. La Niñas are often described in terms of a positive Southern Oscillation Index, which represents the normalised pressure difference between Darwin and Tahiti and gives a positive reading when pressures are high in Tahiti and low in Darwin.3 The index ranges from about -35 to +35.4 During December 2010 the Southern Oscillation Index was +27.1, representing the highest December value on record and the highest monthly value since 1973.5 In turn, Australia experienced an extremely strong La Niña during the end of 2010 and beginning of 2011; the second strongest