Before the Department of Commerce National Telecommunications And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital TV LEHIGH VALLEY COOPERATIVE TELEPHONE ASSN

REMOTE CONTROL GUIDE Cloud DVR - $9.99/mo. With our Cloud DVR service, you can securely store TV, AUD, DVD, POWER your DVR recordings of favorite TV shows and movies in Digital TV VCR, STB Turn on/off a One remote for selected device. multiple devices. the cloud rather than on your local DVR set-top box. LIVE This service provides: Channel Guide SETUP Return to watching Use for programming live TV. sequences of devices • More storage space controlled by the LIST* remote. Displays a list of • Flexible recording recorded shows on REPLAY your PVR/DVR set- • Reliability Skip backwards 10 sec. top box while watching a • Easy availability recording or live TV. SKIP FORWARD Skip forward 30 sec. REWIND while watching a Rewind through recording. Don’t worry about losing your DVR recordings. parts of a recording. FAST FORWARD Ask about our Cloud DVR service! STOP Fast forward through Press to stop parts of a recording. watching a recording or to stop a recording INFO WatchTVEverywhere - that is in progress. Display the current channel and program Free with Basic or Extended Packages MENU info. Press again for Displays applications more detail. WatchTVEverywhere (WTVE) is a free service that comes including the configuration menu. RECORD with your Basic or Extended Basic Package of DigitalTV. Press to record a PLAY show. WTVE gives you the ability to watch many of the pro- Press to watch a recording or control EXIT grams from your home’s TV lineup on your computer, another device Exit the current screen. tablet or smartphone from anywhere you have an internet GUIDE connection — including hotels, vacation homes, airports, Opens the Program PAUSE Guide. -

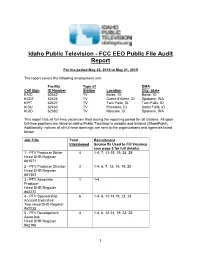

Idaho Public Television - FCC EEO Public File Audit Report

Idaho Public Television - FCC EEO Public File Audit Report For the period May 22, 2018 to May 21, 2019 The report covers the following employment unit: Facility Type of DMA Call Sign ID Number Station Location City, State KAID 62442 TV Boise, ID Boise, ID KCDT 62424 TV Coeur d’Alene, ID Spokane, WA KIPT 62427 TV Twin Falls, ID Twin Falls, ID KISU 62430 TV Pocatello, ID Idaho Falls, ID KUID 62382 TV Moscow, ID Spokane, WA This report lists all full-time vacancies filled during the reporting period for all stations. All open full-time positions are listed on Idaho Public Television’s website and intranet (SharePoint). Additionally, notices of all full-time openings are sent to the organizations and agencies listed below: Job Title Total Recruitment Interviewed Source #s Used to Fill Vacancy (see page 3 for full details) 1 - PTV Producer Writer 4 1-4, 7, 13-15, 19, 24, 28 Hired DHR Register #61571 2 - PTV Producer Director 3 1-4, 6, 7, 13, 14, 19, 28 Hired DHR Register #61363 3 - PTV Associate 1 1-4 Producer Hired DHR Register #62272 4 - PTV Sponsorship 6 1-4, 6, 12-14,19, 23, 28 Account Executive Two Hired DHR Register #62238 5 - PTV Development 4 1-4, 6, 12-14, 19, 23, 28 Associate Hired DHR Register #62196 1 6 - PTV Multi Media Video 2 1-4, 6, 12, 21, 28 Specialist Limited Service (Education) DHR Register #62423 7 - PTV Multi Media Video 1 1-4, 6, 12, 21, 28 Specialist (Communications) DHR Register #62409 8 - PTV Broadcast 2 1-4, 16-18, 28 Maintenance/ Operations Engineer DHR Register #62281 9 - PTV Broadcast 1 1-4, 6, 8, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, Maintenance/ Operations 25-28 Engineer Hired DHR Register #62773 10 - PTV 3 1-4, 19, 28 Director/Videographer Hired DHR Register #00333 11 - Education Outreach 0 1-4, 8, 13 Coordinator Non- Classified. -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

The United States District Court for the Western

Case 2:12-cv-01319-TFM Document 63 Filed 12/12/14 Page 1 of 22 THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA FREEDOM FROM RELIGION : FOUNDATION, INC., DOE 1, by DOE : Case 2:12-cv-01319-TFM 1’s next friend and parent, MARIE : SCHAUB, who also sues on her own : behalf, DOE 2, by Doe 2’s next friend and : parent DOE 3, who also sues on Doe 3’s : own behalf. : : Plaintiffs, : vs. : : NEW KENSINGTON-ARNOLD : SCHOOL DISTRICT, : : Defendant. : PLAINTIFFS’ CONCISE STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS The Origins of the Ten Commandments Monument 1. In late 1956, the New Kensington Fraternal Order of Eagles, Aerie 533, offered a stone monument inscribed with the Ten Commandments to the New Kensington School District Authority (hereinafter the “Ten Commandments Monument”). (Pl. Ex. A, Defendant’s Response to Plaintiff’s First Set of Interrogs., 2-3; Pl. Ex. B, Dec. 3, 1956 Minutes of New Kensington School Board meeting, NewKen-Arnold 00222-00223). 2. The New Kensington School District Authority accepted the Ten Commandments Monument by letter dated December 4, 1956. (Pl. Ex. A, 3; Pl. Ex. C, Dec. 17, 1956 minutes of meeting of New Kensington School District Authority, NewKen-Arnold 00213-00214). 3. The Ten Commandments Monument, which still stands today in its original location, is 6 feet tall and weighs approximately 2,000 pounds. (Pl. Ex. A, 3; Pl. Ex. D, Daily Dispatch Sept. 19, 1957 news article, New-Ken Arnold 00145-00146). 4. The text of the Ten Commandments Monument reads Case 2:12-cv-01319-TFM Document 63 Filed 12/12/14 Page 2 of 22 The Ten Commandments I AM the LORD thy God. -

View the Channel Line-Up

SAINT ANSLEM COLLEGE - HD Channel Line Up Network Channel # Description WBIN - HD 7 Local, NH News WBZ - HD CBS 8 CBS Boston, Local News WCVB-HD ABC 9 ABC Boston, Local News WENH-HD 10 NH Public Television WENH-HD2 11 Maine Public Television WFXT-HD FOX 12 Fox25 Boston, Local News WHDH-HD 13 Local, Boston News Channel 7 WLVI-HD 14 Local News, Boston WMFP-HD 15 Local News, Boston/Lawrence WMUR-HD 16 Local News, Manchester, NH WNEU-HD 17 Telemundo Boston WBTS-HD NBC 18 NBC Boston WSBK-HD 19 my38, CBS affiliate WUNI-HD 20 Univision WUTF-HD 21 uniMas Boston WWDP-HD 22 Evine, Home Shopping CKSH-SD 23 ICI Tele - Montreal Public Television WYDN-SD 24 Christian Programming WFXZ-CD 25 TV Azteca NESN HD 26 New England Sports Network A&E HD 27 Documentaries, Drama, Reality TV CNBC HD 28 Business News & Financial Market Coverage CNN HD 29 24/7 News CNN HN HD 30 CNN Headline News CSNNE BHD 31 Comcast SportsNet New England DISNEY HD 32 Family Friendly, Original shows and movies DSC HD 33 Discovery ESPN HD 34 Worldwide Leader in Sports ESPN2 HD 35 Worldwide Leader in Sports - additional coverage FOOD HD 36 Food Network FOXNEWS HD 37 Breaking & Latest News, Current Events Freeform - TV Series & programming for teens and FREEFRM HD 38 young adults FX HD 39 Fox - Comedy, Drama, Movies GOLF HD 40 Golf Channel HGTV HD 41 Home and Garden Network LIFE HD 42 Lifetime Channel - Female Focused Programming MSNBC HD 43 News Coverage and Political Commentary MTV HD 44 Music, Reality, Drama, Comedies Nickelodeon - Family friendly, programming for NICK HD 45 children -

Television Shopping

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Television shopping: the effect of persuasive strategies on parasocial interaction, subjective well- being, and impulse buying tendency among older women Min-Sun Lee Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Gerontology Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Min-Sun, "Television shopping: the effect of persuasive strategies on parasocial interaction, subjective well-being, and impulse buying tendency among older women" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15331. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15331 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Television shopping: the effect of persuasive strategies on parasocial interaction, subjective well-being, and impulse buying tendency among older women By Min-Sun Lee A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty In partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER of SCIENCE Major: Textiles and Clothing Program of Study Committee: Ann Marie Fiore, Major Professor Mary Lynn Damhorst Mack Shelley Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright © Min-Sun Lee, 2008. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 1453147 Copyright 2008 by Lee, Min-Sun All rights reserved. UMI Microform 1453147 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Honorable Bernard Barnes, Mayor (W/Copy of Encs.)

arter COMMUN CATIONS January 31 , 2017 Hon. Kathleen H. Burgess, Secretary NYS Public Service Commission Three Empire State Plaza Albany, NY 12223-1350 RE: Franchise Renewal - Time Warner Cable Northeast LLC With the Village of St. Johnsville Dear Secretary Burgess: We are herewith filing, via email, the following: 1 . R-2 Application for Franchise Renewal, channel Iineup and rates 2. Municipal Resolution granting renewal dated April 19, 2016 3. FullyexecutedcopyofFranchiseRenewalAgreementdatedNovember21,2016 4. Copy of Iatest annual test data compiled for this part of the Division's CATV System at PSC 5. Published Iegal notices We hereby request approval by the Commission of this application pursuant to Section 222 of the Public Service Law. Sincerely, Kevin Egan Director, Government Affairs Charter Communications Enclosures cc: Honorable Bernard Barnes, Mayor (w/copy of Encs.) 20 Century Hill Drive Latham, NY 12110 STATE OF NEW YORK PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION In the matter of application of Time Warner Cable Northeast LLC, locally known as Charter Communications, for renewal of its Certificate of Confirmation and Cable Teleyision Franchise in the Village of St. Johnsvil}e, Montgomery County, New York. Tlie exact legal name of the applicant is Time Warner Cable Northeast LLC. The applicant does business under the name Charter Communications. Applicant's teleplione number is: (518) 640-8575 4. & 5. The applicant serves the following municipalities from the same headend or from a different headend in the same or adjacent counties; the number of subscribers in eacli of the coimnunities as of January 2017 are: Village of Arnes - 36 Town of Canajoharie - 81 Village of Canajoharie - 523 Village of Fort Plain - 557 Town of Minden - 61 Village of Nelliston - 119 Village of Palatine Bridge - 223 Town of Palatine - 49 Town of Root - 31 Town of St. -

Communications Media and the First Amendment: a Viewpoint- Neutral FCC Is Not Too Much to Ask For

Federal Communications Law Journal Volume 53 Issue 1 Article 3 12-2000 Communications Media and the First Amendment: A Viewpoint- Neutral FCC Is Not Too Much to Ask For Helgi Walker Federal Communications Commission Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj Part of the Communications Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Helgi (2000) "Communications Media and the First Amendment: A Viewpoint-Neutral FCC Is Not Too Much to Ask For," Federal Communications Law Journal: Vol. 53 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/fclj/vol53/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Federal Communications Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Communications Media and the First Amendment: A Viewpoint-Neutral FCC Is Not Too Much to Ask For Helgi Walker* I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 5 11. THE UNIQUELY DISFAVORED STATUS OF VIEWPOINT-BASED LAWS IN FIRST AMENDMENT JURISPRUDENCE ............................. 6 Il. A VMWPOINT-NEUTRALFCC IS NOTTOO MUCHTO ASK FOR ........ 10 A. The Identificationand Avoidance of Viewpoint-Based Regulation.............................................................................. 10 B. An Agency Policy Against DiscretionaryViewpoint -

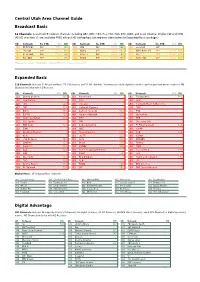

Central Utah Area Channel Guide Broadcast Basic

Central Utah Area Channel Guide Broadcast Basic 12 Channels: Local Utah Broadcast channels including ABC, NBC, CBS, Fox, PBS, PAX, BYU, KJZZ, and Local Channel 10 plus CW and UEN. (All HD channels {} are available FREE without HD set top box, but requires subscription to Expanded Basic package.) SD Network No STB DTV HD SD Network No STB DTV HD SD Network No STB DTV HD 102 KUTV CBS 02* {77-1} 502 106 ION 06* {81-13} 506 110 Local 10 10* 103 The CW 03* {81-3} 503 107 KUED 07* {80-3} 507 111 KMTI-Retro TV 11* {106-1} 511 104 KTVX ABC 04* {77-11} 504 108 BYU-TV 08* {106-2} 508 112 KJZZ 12* {79-13} 512 105 KSL NBC 05* {78-3} 505 109 KUEN 09* {80-13} 509 113 KSTU FOX 13* {79-3} 513 *Broadcast Basic customer without digital set-top box (STB) must use analog channels 02-13. Expanded Basic 120 Channels: Includes 12 Broadcast Basic, 55 SD Channels and 52 HD channels. You may also add a digital receiver to get the premium movie channels. HD Channels included with HD Receiver. SD Network DTV HD SD Network DTV HD SD Network DTV HD 114 Disney Channel 515 135 Paramount 162 Fox Business 562 115 New Nation 136 CMT 163 INSP 116 TBS 516 140 TV Land 164 Hallmark Movie & Mysteries 117 TNT 517 141 Hallmark Channel 170 FXM 118 ESPN 518 142 Cartoon Network 554 171 RFD 119 ESPN2 519 143 Outdoor Network 557 172 Sportsman 120 AT&T SportsNet 520 144 MTV 185 TBN 121 CBS Sports 145 VH1 186 Discovery Life 122 FOX News 522 146 Comedy Central 187 E! Entertainment 587 123 CNN 149 QVC 188 ESPNU 124 Weather Channel 150 Travel Channel 550 189 Golf 598 125 Nick 151 tru TV 551 190 CSPAN 126 USA Network 526 152 SyFy 552 191 OXYGEN 127 Lifetime 527 153 Bravo 553 192 History 128 Freeform 528 154 MSNBC 555 193 OWN 129 A&E 529 155 Home Shopping Network 194 Fox Sports 1 589 130 AMC 156 CNBC 556 195 FXX 131 Discovery 531 158 NFL Network 196 National Geographic 595 132 TLC 532 159 HLN 197 I.D. -

EMPLOYEE NEWSLETTER | KUTV, KMYU, KJZZ ISSUE 7 Employee Newsletter

EMPLOYEE NEWSLETTER | KUTV, KMYU, KJZZ ISSUE 7 Employee Newsletter KENT’S CORNER Welcome to spring everyone! President and the alleged abuse It’s nice to have the Olympics in has been stellar. Far better than our rear-view mirror and on to the any of our competitors. most exciting sports event in the These big stories define us and March 2018 U.S. March Madness! our coverage is certainly defining We did get some wins in our our alert, empower, protect February ratings performance strategy. with a #1 finish in the 5 pm and Thanks to engineering for 6pm news, #1 in Entertainment keeping us on the air despite our Tonight, and 5 out of the top 6 faulty switcher. Glad we have a prime with CBS network shows, new one on the way! NOTES FROM HR excluding Olympics. The days Welcome to all the new Referring a friend is easy! If your that we were not up against employees, we are closer to being referral is hired and successfully Olympics our news ratings faired fully staffed now, and it is making completes their introductory period, very well! a difference in our operations. you will receive a referral bonus! Our sales departments for all Everyone has worked hard all Go to the referral site at three stations are performing well quarter and I thank all of you for sinclair.employeereferrals.com to and making a run at first quarter your efforts to make our place a refer a friend. budget. They are all focused on great place to work. NEW EMPLOYEES new business development with a Two Goals to stay focused on: Say hi to the new big seminar in April. -

Television Channel Guide • 1-877-666-4932

OmniTel Communications TELEVISION CHANNEL GUIDE www.omnitel.biz • 1-877-666-4932 Essential TV $36.95 49 Big Ten Iowa HD 133 Bravo Premium Packages 50 NFL NETWORK 134 Bravo HD 1 OmniTel 51 NFL Network HD 135 FYI HBO $17.00 2 KMTVDT3 (Escape) 52 The Golf Channel 136 FYI Channel HD 290 Home Box Office 3 KMTV (CBS) 53 The Golf Channel HD 137 E! Entertainment Television 291 HBO HD 4 KMTV HD (CBS HD) 54 Fox Sports 1 138 E! Entertainment Television HD 292 HBO 2 5 KMTVDT2 (Laff TV) 55 Fox Sports 1 HD 141 The Travel Channel 294 HBO Signature 56 Fox Sports Midwest Plus 142 The Travel Channel HD 6 WOWT (NBC) 296 HBO Family HD 143 Cooking Channel 298 HBO Comedy 7 WOWT HD (NBC HD) 57 NBCSN 145 Food Network 300 HBO Zone 8 WOWTDT2 (Cozi TV) 58 NBCSN HD 146 Food Network HD 9 WOWTDT3 (Antenna TV) 59 Outdoor Channel 147 Home & Garden Television Cinemax $13.00 11 KDIN (PBS) 60 Outdoor Channel HD 148 HGTV HD 310 CineMAX 12 KDIN HD (PBS HD) 62 Fox Sports 2 149 Do-It-Yourself Network 311 CineMAX HD 63 Fox Sports 2 HD 155 History 13 KDIN-DT2 (Kids) 312 MoreMAX 64 NBC Sports Chicago Plus 156 History HD 14 KDINDT2 (Kids HD) 314 ActionMAX HD 69 TNT 157 Viceland 15 KXVO (CW) 316 ThrillerMAX 70 Turner Network TV HD 158 Viceland HD 16 KXVO HD (CW HD) 71 USA Network 159 Military History Channel 318 CineMAX Spanish 17 KXVODT2 (This TV) 72 USA Network HD 163 National Geographic USA 320 MovieMAX 18 KPTM (Fox) 73 FX 164 National Geographic HD 322 OuterMAX 19 KPTM HD (Fox) 74 FX HD 181 National Geographic Wild 324 5 StarMAX 20 KPTMDT2 (My Network 75 Paramount Network 182 -

Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media Entity Fox News Channel Oct. 96 NewsCoqJ. Fox Reality May 05 News Corp. Fox Sports Net Nov. 97 News Corp. Fox Soccer Channel (fonnerly Fox Sports World) Nov. 97 News Corp. FX Jun. 94 News Corp. Fuel .luI. 03 News Corp. Frec Speech TV (FSTV) Jun. 95 Game Show Network (GSN) Dec. 94 Liberty Media Golden Eagle Broadcasting Nov. 98 preat American Country Dec. 95 EW Scripps Good Samaritan Network 2000 Guardian Television Network 1976 Hallmark Channel Sep.98 Liberty Media Hallmark Movie Channel Jan. 04 HDNET Sep.OI HDNET Movies Jan. 03 Healthy Living Channel Jan. 04 Here! TV Oct. 04 History Channel Jan. 95 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst History International Nov. 98 Disney, NBC-Universal, Hearst (also called History Channel International) Home & Garden Television (HGTV) Dec. 94 EW Scripps Home Shopping Network (HSN) Jul. 85 Home Preview Channel Horse Racing TV Dec. 02 !Hot Net (also called The Hot Network) Mar. 99 Hot Net Plus 2001 Hot Zone Mar. 99 Hustler TV Apr. 04 i-Independent Television (fonnerly PaxTV) Aug. 98 NBC-Universal, Paxson ImaginAsian TV Aug. 04 Inspirational Life Television (I-LIFETV) Jun. 98 Inspirational Network (INSP) Apr. 90 i Shop TV Feb. 01 JCTV Nov. 02 Trinity Broadcasting Network 126 Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Programming Service Launch Ownership by Date "Other" Media EntIty ~ewelry Television Oct. 93 KTV ~ Kids and Teens Television Dominion Video Satellite Liberty Channel Sep. 01 Lifetime Movie Network .luI. 98 Disney, Hearst Lifetime Real Women Aug.