AUSTRALIA NOTES for READING GROUPS Brendan Cowell HOW IT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint)

-Season Three- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint) Toby Stephens was born in London, England and trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA). He has gained critical acclaim as a stage and screen actor and upcoming work includes the feature film 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi directed by Michael Bay, and And Then There Were None for the BBC. He will also star opposite Timothy Spall and John Hurt in Nick Hamm’s The Journey. Previous television roles include: “Vexed” (BBC), “Robin Hood” (BBC), “Wired” (ITV), “The Wild West” (BBC 1), “Jane Eyre” (BBC 1), “Sharpe’s Challenge” (ITV), “The Best Man” (ITV), “The Queen’s Sister” (Channel 4), “Waking the Dead” (BBC 1), “Poirot” (ITV), “Cambridge Spies” (BBC 2), “Perfect Strangers” (BBC 2), and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” (BBC 1). Recent film credits include: Believe with Natasha McElhone and Brian Cox, All Things to All Men alongside Gabriel Byrne and Rufus Sewell, and the lead role in The Machine for Content Film. Other film work includes: Severance, The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey, Die Another Day, Possession, The Announcement, Onegin, Photographing Fairies, Sunset Heights, Cousin Bette, The Great Gatsby, Twelfth Night, and Orlando. Toby is an accomplished stage actor, both in London’s West End and on Broadway. Theater credits include ‘Elyot’ opposite Anna Chancellor in “Noel Coward’s Private Lives,” ‘Georges Danton’ in “Danton’s Death” (National Theatre Olivier), ‘Henry’ in “The Real Thing” (The Old Vic), ‘Thomas’ in “A Doll’s House,” ‘Jerry’ in -

Nowhere Boys: the Book of Shadows, Mini-Series Seven Types of Ambiguity, and Barracuda

Introduction The wait is over…Australia’s award-winning drama series Glitch returns to ABC, Thursday 14 September at 8.30pm with all episodes stacked and available to binge watch on ABC iview. When it first premiered in 2015, Glitch broke the mold and garnered fans around the country, who became immersed in the story of the Risen - the seven people who returned from the dead in perfect health. With no memory of their identities, disbelief soon gave way to a determination to discover who they are and what happened to them. Featuring a stellar cast including: Patrick Brammall, Emma Booth, Emily Barclay, Rodger Corser, Genevieve O’Reilly, Sean Keenan, Rob Collins and Hannah Monson, Glitch is an epic paranormal saga about love, loss and what it means to be human, and the dark secrets that lie beneath our country’s history. Season two picks up with James (Patrick Brammall), dealing with his recovering wife, Sarah (Emily Barclay) and a new-born baby daughter. He continues to be committed to helping the remaining Risen unravel the mystery of how and why they have returned and shares with them his discovery that Doctor Elishia Mackeller (Genevieve O’Reilly), now missing, died and came back to life four years ago and has been withholding many secrets from the beginning. Meanwhile on the run and desperate, John Doe (Rodger Corser) crosses paths with the mysterious Nicola Heysen (Pernilla August) head of Noregard Pharmaceuticals. Sharing explosive information with him, she convinces him that that the only way to discover answers to his questions is to offer himself up for testing inside their facility. -

I Love You Too

I Love You Too All that stands between them are four little words A film written by Peter Helliar Directed by Daina Reid Produced by Laura Waters & Yael Bergman Production Company: Princess Pictures “I Love You Too” opens in cinemas nationally on May 6th 2010 Materials are available for download from http://publicity.roadshow.com.au I LOVE YOU TOO SYNOPSIS One line: A romantic buddy movie about the meaning of relationships, the importance of friendship, and having the courage to pursue the one you love. One paragraph: A romantic buddy movie about the meaning of relationships, the importance of friendship, and having the courage to pursue the one you love. Written by comedian Peter Helliar, I LOVE YOU TOO stars Brendan Cowell as Jim, a 30-something emotionally stunted man whose inability to declare his love to his girlfriend, Alice, threatens to cost him the best thing he ever had but leads him to befriend a talented dwarf who helps him find the words to get her back. About the team: I LOVE YOU TOO is written by comedian Peter Helliar (ROVE, BEFORE THE GAME), is directed by Daina Reid (VERY SMALL BUSINESS) and was developed and produced by Princess Pictures’ Laura Waters, the award-winning producer of SUMMER HEIGHTS HIGH and WE CAN BE HEROES and Yael Bergman, co-writer and co-producer of LOVE AND OTHER CATASTROPHES. I LOVE YOU TOO stars Brendan Cowell (NOISE, LOVE MY WAY) as Jim, a 30-something emotionally stunted man whose inability to declare his love to his girlfriend, Alice, threatens to cost him the best thing he ever had. -

Season Two- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint)

-Season Two- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint) Toby Stephens was born in London, England and trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA). He has gained critical acclaim as a stage and screen actor. In 2011, Toby starred as ‘Jack Armstrong’ in the BBC Comedy Drama “Vexed.” Previous television roles include “Robin Hood” (BBC), “Wired” (ITV), “The Wild West” (BBC 1), “Jane Eyre” (BBC 1), “Sharpe’s Challenge” (ITV), “The Best Man” (ITV), “The Queen’s Sister” (Channel 4), “Waking the Dead” (BBC 1), “Poirot” (ITV), “Cambridge Spies” (BBC 2), “Perfect Strangers” (BBC 2), and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” (BBC 1). In 2012 Toby filmed Believe with Natasha McElhone and Brian Cox, and in 2013 starred as one of the leads in All Things to All Men alongside Gabriel Byrne and Rufus Sewell. Toby also wrapped filming in Caradog James’ The Machine for Content Film. Other film work includes: Severance, The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey, Die Another Day, Possession, The Announcement, Onegin, Photographing Fairies, Sunset Heights, Cousin Bette, The Great Gatsby, Twelfth Night, and Orlando. Toby is an accomplished stage actor – both in London’s West End and on Broadway. Theater credits include ‘Elyot’ opposite Anna Chancellor in “Noel Coward’s Private Lives,” ‘Georges Danton’ in “Danton’s Death” (National Theatre Olivier), ‘Henry’ in “The Real Thing” (The Old Vic), ‘Thomas’ in “A Doll’s House” and ‘Jerry’ in “Betrayal” (Donmar Warehouse), ‘Mr. Horner’ in “The Country Wife,” ‘Anthony Cavendish’ in “The Royal Family,” ‘Japes’ -

¾ the World at Your Feet!

JhWdi79JegdjYanegZhZcihi]Z½ 12th CANBERRA INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL Wednesday 29 October – Sunday 9 November 2008 PROGRAM DENDY CINEMA Dendy Cinemas Canberra Level 2, North Quarter Canberra Centre ARC CINEMA National Film and Sound Archive McCoy Circuit Acton ¾j^[mehbZ Wjoekh\[[j canberrafilmfestival.com.au The Canberra International Film Festival is proudly presented by … Welcome Some years ago I spent some time in New Orleans and fell in love with Creole cooking. I met the owner of a great little bookstore who Canberra International Film Festival acknowledges the financial assistance of showed me a cookbook (she said her mother swore by it) called Talk About Good. Why am I talking about Creole cooking and a book? Because this year’s Festival feels like it has all the right ingredients and recipes – a gumbo for every palate – talk about good! The festival has expanded considerably – 75 screenings, 41 films, Founding Partner Major Partners 12 days – and served from the state-of-the-art facilities at the Dendy Cinemas and Arc Cinema. Screenings at the NFSA are legendary, and this year there are 5 totally gourmet selections, including Fassbinder’s epic. Another new ingredient is that most days will have screenings from lunch through to supper, so there’s an opportunity for everyone to taste what the world has to offer. Each day is jam packed with cinematic delights. The Festival is only made possible through the commitment of our dedicated partners. The University of Canberra, our founding partner, continues its support, as does DHL Worldwide Express Corporate Partners who constantly amaze us by how swiftly they transport prints around the globe. -

A Study Guide by Anne Chesher

© ATOM 2013 A STUDY GUIDE BY ANNE CHESHER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-355-7 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au INTRODUCTION 1814. Van Diemen’s Land, the notorious British penal colony, has dissolved into chaos. Outlaws roaming the wilderness have pushed the colonial government to breaking point. Driven by a deep sense of loyalty and an unquenchable hatred towards those he once served, English convict Michael Howe and a young Aboriginal girl turn a desperate band of convicts, deserters and bushmen into a fear- some guerrilla army and lead them in open rebel- 2013 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION lion against the brutal, corrupt establishment. As the British hunt the outlaws, Howe remains an elusive prize. In desperation, the Governor makes the capture of Howe’s pregnant girl his priority. An epic story of love and betrayal, The Outlaw Michael Howe (Brendan Cowell, 2013) chronicles the astonishing true story of the man who pushed Australia to the brink of civil war. 2 Curriculum The Outlaw Michael Howeis an ideal resource for the teaching and learning of Australian history. It is particularly relevant to the Australian History Curriculum (ACARA 2009) for secondary school students Years 7–10, as the film is set during the settlement of Van Diemen’s Land during the British criminal transportation era. The film presents a clear depiction of a period of voluntary and forced movement of people from the ‘Old World’ to the ‘New World’, and faithfully recreates the accompanying social, cultural and political developments. Additionally, the characters and personalities of key figures during that time – namely Governors Davey and Sorell, outlaws John Whitehead and Michael Howe, along with the fearsome ‘Black Mary’ and the traitorous Maria Lord – are closely examined. -

Brendan Cowell

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Brendan Cowell Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian Smyth +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected] Address Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Film Title Role Director Production Company AVATAR SEQUELS Scoresby James Cameron Twentieth Century Fox THE CURRENT WAR Confederate Soldier Alfonso Gomez-Rejon The Weinstein Company LAST CAB TO DARWIN Publican Jeremy Sims Last Cab Productions BROKE Dirk Heath Davis Scope Red OBSERVANCE Employer Joseph Sims-Dennett Sterling Cinema THE DARKSIDE Tyrone Warwick Thornton Scarlett Pictures Robyn Kershaw SAVE YOUR LEGS! Rick Boyd Hicklin Productions BENEATH HILL 60 Nominated for the Best Lead Actor in a Feature Film Award, Australian Film Institute Captain Oliver Woodward Jeremy Sims The Silence Productions Awards, 2010 I LOVE YOU TOO Jim Daina Reid Princess Pictures THREE BLIND MICE Glenn Matthew Newton Dirty Rat Films TEN EMPTY Shane Hackett Anthony Hayes Yeah Right Films NOISE Winner of the Best Lead Actor in a Feature Film Award, Film Critics Circle Awards, 2007 Nominated for the Best Lead Actor in a Feature Film Award, Australian Film Institute Graham Matthew Saville Retro Active Films Awards, 2007 Nominated for the Best Actor Award, Inside Film Awards, 2007 Australian Film Finance SUBURBAN MAYHEM Interviewer (Voice) Paul Goldman Corp. DECK DOGZ Kurt Steve Pasvolsky BJ Films TO END ALL WARS Wallace Hamilton David L. Cunningham Argyll Film Partners THE MONKEY'S MASK Hayden Samantha Lang Arenafilm CITY LOOP Robert Belinda -

Download Press

Ticket to Ride, Screenwest and Lotterywest presents In association with Screen Australia, Spectrum Films, Red Apple, Head Gear Films / Metrol Technology / Kreo Films / a See Pictures production 1% Directed By: Stephen McCallum Screenplay By: Matt Nable Produced By: Jamie Hilton & Michael Pontin Executive Producers: Josh Pomeranz Viv Scanu Stephen Boyle Phil Hunt Compton Ross Cast: Ryan Corr Abbey Lee Simone Kessell Josh McConville With Matt Nable And Aaron Pederson Production Partners: Spectrum Films Red Apple Cameras Head Gear Films Run Time: 92 minutes Rated: TBC Language: English Sound: 5.1 Year of Production: 2017 TIFF PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES AGENT CONTACT Maxine Leonard PR Celluloid Dreams UTA +1 (323) 930-2345 +33 (1) 49 70 03 70 +1 (310) 246-6033 Jennifer Nguyen [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Hilda Somarriba [email protected] One Line Synopsis: When the vice president of an outlaw motorcycle gang has to betray his president to save his brother it results in civil war. Short Synopsis: 1% is a story of brotherhood, loyalty and betrayal set within the primal underworld of outlaw motorcycle gangs. It follows Paddo, heir to the throne of the Copperheads MC, who has to betray his president to save his brother’s life. When this betrayal leads to a split in the club it results in civil war, forcing Paddo to choose between loyalty and blood. Synopsis: In the world of Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs, power belongs to those strong enough to hold it. Welcome to the dangerous, uncompromising and primal world of the Copperheads MC, welcome to the 1%. -

TOBY OLIVER ACS CINEMATOGRAPHY Agent • Edwina Stuart, HLA Management Ph +61 2 9549 3000 Mobile Ph

SEP 2012 TOBY OLIVER ACS CINEMATOGRAPHY Agent • Edwina Stuart, HLA Management ph +61 2 9549 3000 Mobile ph. • +61 (0) 418 271 931 Web • http://www.tobyoliver.com Email • [email protected] IMDB page • http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0002947 FEATURES 33 POSTCARDS (Aust/China) Mei Mei Productions, Hengdian World Studios (China), Screen NSW 2011 prod: Lesley Stevens, Penny Carl dir/prod: Pauline Chan RED MX Digital 4K, 97mins Cast: Guy Pearce, Claudia Karvan, Zhu Lin, Lincoln Lewis Official Australian/Chinese Co-Production. Released widely in China Sept 2011 Sydney Film Festival 2011, Winner CRC Award Shanghai International Film Festival 2011, Winner Rising Star Award Singapore International Film Festival 2011 Melbourne International Film Festival 2011 BENEATH HILL 60 Paramount/Transmission, The Silence Productions, Screen Australia 2010 prod: Bill Leimbach, David Roach dir: Jeremy Sims Super 35mm 3-perf, 110mins Cast: Brendan Cowell, Gyton Grantley, Steve LeMarquand, Anthony Hayes, Aden Young Australian cinema release in April 2010 Winner Sloan Prize Hamptons Film Festival USA 2010 Winner Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor Savannah Film Festival USA 2010 NOMINATED for 12 AFI Awards 2010, incl Best Cinematography & Best Film WINNER GOLD AWARD for Cinematography 2010 ACS Awards NSW CANE TOADS THE CONQUEST 3D Discovery, Fern St Films, Participant Media, dir/prod: Mark Lewis 2010 (Documentary feature) Prep and Northern Territory block Digital Stereoscopic 3D, 90mins Co-DOP: Kathryn Milliss (QLD block), Paul Nicola (NSW & Studio) Silicon Imaging -

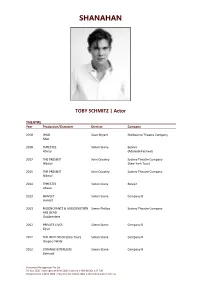

TOBY SCHMITZ | Actor

SHANAHAN TOBY SCHMITZ | Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2018 WILD Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Man 2018 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus (Adelaide Festival) 2017 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai (New York Tour) 2015 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai 2014 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus 2013 HAMLET Simon Stone Company B Hamlet 2013 ROSENCRANTZ & GUILDENSTERN Simon Phillips Sydney Theatre Company ARE DEAD Guildenstern 2012 PRIVATE LIVES Simon Stone Company B Elyot 2012 THE WILD DUCK (Oslo Tour) Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle 2012 STRANGE INTERLUDE Simon Stone Company B Edmund Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2012 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Malthouse Season Gregers Werle 2011 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING John Bell Bell Shakespeare Benedick 2011 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle 2010 MEASURE FOR MEASURE Benedict Andrews Company B Lucio 2010 HAMLET David Berthold La Boite Theatre Company Hamlet 2009 TRAVESTIES Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Tristan Tzara 2009 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2008 RABBIT Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Richard 2008 THE GREAT Peter Evans Sydney Theatre Company Peter & Didi 2008 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2007 SELF ESTEEM Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Chad 2006 THE EMPEROR OF SYDNEY David Berthold Griffin -

Ben Mathews Acting Resume May 2020

BENJAMIN MATHEWS A U S T R A L I A N & A M E R I C A N C I T I Z E N Lisa Mann Creative Management [email protected] +61-2-9387-8207 ACTOR As an actor, Ben has appeared in film, television and in over 30 plays in New York, Los Angeles and Sydney. Below are some of the highlights: THEATRE We Are The Himalayas Nikolai Bukharin Brave New Word A Hard God (Opposite Jackie Weaver) Joe Cassidy Sydney Theatre Company Men (Directed by Brendan Cowell) Guy Melbourne Fringe & off-Off-Broadway An Adult Evening of Shel Silverstein (Opposite Rose Byrne) Gibby The Practical Theatre Company Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs Malcolm Darlinghurst Theatre Powerplays Arle Downstairs Belvoir Street Black Codes Mike Sanford Meisner Theatre, NYC The Zoo Story Jerry The Kraine Theatre, New York The Balcony The General Atlantic Theater Company Black Comedy Brindsley Triangle Theatre Co. NYC Romeo & Juliet Benvolio Central Theatre, New York IMPROV The Magnificent Finger-Gunners Multiple Sydney Fringe Festival & Giant Dwarf (Improv Troupe) TELEVISION Happy People Suck (Pilot) Steven TruTV (America) - from Emmy-winners Tracey Baird & Krysia Plonka BedHead Mister Chief ABC In a Woman’s World Billy ABC Love My Way Evan Southern Star/Fox 8 All Saints Rich Seven Network FILM Nineteen Henry Dir. Madeline Kelly Crushed Aidan Dir. Megan Riakos Siren The Man Dir. Kavi Jarrott Seduce Don Dir. Kavi Jarrott Reunion Cal Prod. Clark Gregg The Speaker The Director Dir. Julian Shaw Falling Fowl Miles Dir. Lucy Hayes Pop’s Dream Stuart Dir. -

Ruben Guthrie

Company B presents RUBEN GUTHRIE Photo: Alex Craig Written by Brendan Cowell Directed by Wayne Blair Teacher’s Notes EDUCATION PARTNER Company B Company B sprang into being out of the unique action taken to save the Nimrod Theatre building from demolition in 1984. Rather than lose a performance space in inner city Sydney, more than 600 arts, entertainment and media professionals as well as ardent theatre lovers, formed a syndicate to buy the building. The syndicate included nearly every successful person in Australian show business. Company B is one of Australia’s most celebrated theatre companies. Under the artistic leadership of Neil Armfield, the company performs at its home at Belvoir St Theatre in Surry Hills, Sydney and from there tours to major arts centres and festivals both nationally and internationally. Company B engages Australia’s most prominent and promising playwrights, directors, actors and designers to present an annual artistic program that is razor-sharp, popular and challenging. Belvoir St Theatre’s greatly loved Upstairs and Downstairs stages have been the artistic watering holes of many of Australia’s great performing artists such as Geoffrey Rush, Cate Blanchett, Jacqueline McKenzie, Noah Taylor, Richard Roxburgh, Max Cullen, Bille Brown, David Wenham, Deborah Mailman and Catherine McClements. Sellout productions like Cloudstreet , The Judas Kiss , The Alchemist , Hamlet , Waiting for Godot , Gulpilil , The Sapphires , Stuff Happens , Keating! , Parramatta Girls, Exit the King and Toy Symphony have consolidated Company B’s position as one of Australia’s most innovative and acclaimed theatre companies. Company B also supports outstanding independent theatre companies through its annual B Sharp season.