Do People Mix at Mixers? Structure, Homophily, and the “Life of the Party”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornell University. Library. Administration. ~ Cornell University Library Records, [Ca.186§- 107.4 Cubic Ft

# 13\01\1082 Cornell University. Library. Administration. ~ Cornell University Library records, [ca.186§- 107.4 cubic ft. Summary: Correspondence relating to the development and administration of the library, general administrative files, administrative files of Librarians Otto Kinkeldey and Stephen McCarthy, financial records, statistical reports, and grant files. Also, records pertaining to the construction of the John M. Olin Library, including correspondence and reports of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Library Building Program; preliminary drawings; architectural drawings and blueprints; booklets, brochures, and papers relating to the dedication ceremonies; Library of Congress files, 1958-1986; ALA and ARL files, 1949-1985; Collection Development and Management Project files and user survey, 1978-1981; file relating to Cornell's decision to join RLG, 1978-1979; scrapbook of clippings of events connected with the library, 1984-1990; results of a poll of library employees, c. 1975; files of the Librarian (primarily Louis Martin and Gormly Miller) relating to departments in Olin Library including Circulation, History of Science, Icelandic, Interlibrary Loan, Manuscripts and University Archives, Maps, Microtexts, and Newspapers, the New York Historical Resources Center, and Reference, 1968-1989. Summary: Also, forty-five panels depicting the architectural evolution and design of Kroch Library; photo album of a 1990 visit by Asian dignitaries, a 1980 User Survey, a code book of detailed work done by several departments (1891•'- 1923) including special collection bookplates, and slides and audiocassettes describing the library. Restricted to ermission of office of origJ.!h_ Boxes 58-70, 73 are not restricted. Finding aids: Box lists. Finding aids: Folder lists. Includes collection #13/1/1287. -

Cornell University Policy Office Policy.Cornell.Edu

Cornell University Policy Office policy.cornell.edu Policy 3.1 University Fundraising Responsible Executive: Vice President, Alumni Affairs and Development Responsible Office(s): Division of Alumni Affairs and Development Originally Issued: November 1983 Current Version Approved: June 19, 2019 Last Updated: August 9, 2021 Table of Contents 1. Policy Statement and Requirements .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Policy Statement ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Scope ........................................................................................................................................ 2 1.3 Policy Requirements ................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Collection and Retention of Information................................................................................. 6 1.5 Compliance ...............................................................................................................................7 1.6 Resources ..................................................................................................................................7 2. To Whom This Policy Applies ....................................................................................................... 8 3. Definitions .................................................................................................................................... -

Comstock Publishing Associates /Cornell University Press

COMSTOCK PUBLISHING ASSOCIATES /CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cornellpress.cornell.edu MONARCHS IN A CHANGING WORLD Biology and Conservation of an Iconic Butterfly edited by Karen S. OberhauSer, Kelly r. nail, SOnia altizer ISBN: 978-0-8014-5315-1 | 352 pages | $35.00/£21.50 hardcover “Few other species capture the imagination and provide fodder for knowledge and innovation like the monarch. Monarchs in a Changing World is a beautiful illustration of both.”—Jessica Hellmann, University of notre Dame “Monarchs in a Changing World summarizes work that reinforces, extends, and ameliorates our understanding of the biology of the monarch butterfly, with a particular focus on key research, conservation, and outreach efforts that aim to preserve this species, its range and habitats, and its awe-inspiring long-distance migration in eastern North America. This book presents a variety of interesting and thought-provoking topics to readers. They range from studies on the population dynamics and ecology of monarchs in different areas around the globe to current and ongoing conservation and management efforts that span personal, local, state, national, and international boundaries. This book will serve as the key resource for those people interested in using monarch butterflies as a model organism in citizen science, science literacy, and environmental education programs.”—steven m. reppert, mD, Umass meDical scHool Karen S. OberhauSer is a Professor in the Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology at the University of Minnesota. She is coeditor of The Monarch Butterfly: Biology and Conservation, also from Cornell. Kelly r. nail is a PhD candidate in the Conservation Biology Program at the University of Minnesota. -

The Ithacan, 1973-02-08

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 1972-73 The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 2-8-1973 The thI acan, 1973-02-08 The thI acan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1972-73 Recommended Citation The thI acan, "The thI acan, 1973-02-08" (1973). The Ithacan, 1972-73. 16. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_1972-73/16 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 1970/71 to 1979/80 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 1972-73 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ,r • ' ,. .'. • ' ' .. · ~-~ -- ......... ·- "·_-, .... ,,., 9 1973 I CA COUEG BRARY erials ca, wYork. Vol. XL I No. 17 Febru The Divine Light 'SOUNDS 0-F_ BL_ACK-NESS' FACI.NG H_ARD TIMES ··., ..~- ·_ ..~ .- ;,,. e·y Sheldon Julius doesn't seem to realize that all Management's Reasoning "Rock _music today, whether of Ithaca isn't enthused with Questioned by the Rolling Stqnes, Curtis progressive rock. There are, Thus black programming was r. , , Mayfield or the Jefferson indeed, other forms of music reduced to 8 hours and 45 ·i-'."", SATQURU MAHARAJ ,i Airplane can trace most of its that are enjoyable to the ·-:::, ,.,;,.-- . minutes. These hours were form and content to the rhythm listening audience. Currently, spread over two days, Saturday ·· · <:.lJf.Tom-Threlkeld '· years old,. this God-energy and blues music that was bQrn since the · cutting of the and Sunday. After the Xmas :\!,Wbei'.the world needs reportedly entered the soul of and bred exclusively by the. -

Getting to Cornell University Ithaca Campus

Getting to Cornell University Ithaca Campus: Air Service - Direct Air Service is available to Ithaca. In addition, air service is available to a number of other regional airports. Ithaca Airport: Ithaca, New York -- 10 miles from campus The Ithaca Tompkins Regional Airport: flyithaca.com Located on Brown Road in Ithaca, NY, 10-minute drive from campus and downtown areas, the area is serviced by the following: • Continental Airlines: www.continental.com • US Airways: www.usairways.com • Northwest Airlines: www.nwa.com Ground Transport in Ithaca: Taxi: Ithaca Dispatch www.ithacataxi.biz • University Taxi: (607) 277-7777 • Cayuga Taxi: (607) 277-TAXI (8294) • Yellow Cab Co: (607) 277-CABS (2227) or Toll Free: 1-888-321-1149 Local bus: Tompkins Consolidated Area Transit (TCAT): www.tcatbus.com (607) 277-7433 Buses are the cheapest options to Cornell. Route 31 serves the Ithaca airport. Rental Cars: • AVIS Reservations: 1-800-831-2847 - www.avis.com • Hertz Reservations: 1-800-654-3131 - www.hertz.com Local Office: (607) 257-8677 Hotel Shuttles: The following conference hotels offer free airport shuttle service: The Statler Hotel, Cornell University: 1-800-541-2501 Holiday Inn Downtown Ithaca: (607) 257-2500 Hilton Garden Inn Ithaca: (607) 277-8900 Other Regional Airports Syracuse, New York Syracuse Hancock International Airport: www.syrairport.org Located in Syracuse, NY, approximately 60 miles north of Cornell University with an estimated driving time of 1 hour and 30 minutes. Shuttle Service from Syracuse Airport to Ithaca: Commencement Connections – http://commencementconnections.com/events/ ashe Rental Cars: • Alamo/National (800) 227-7368 • Avis (800) 331-1212 • Budget (800) 527-0700 • Dollar (800) 800-3665 • Enterprise (800) 325-8007 • Hertz (800) 654-3131 • Thrifty (off-airport car rental provider, with continuous shuttle service) (800) 847-4389. -

Cornell Class of 1953 Memoir Ebook 2019

CORNELL CLASS OF 1953 MEMOIR EBOOK 2019 1956 Baby Reunion Dear Class of '53, Here are the stories, bios and some pictures from your 36 classmates who responded to the request to submit to our '53 Memoir Ebook. This gives a heartfelt and emotional experience, with some smiles, to read the offerings. Thanks to the many who shared personal information and memories. This Ebook is in PDF. You may have to click Maximize box, the right top of your screen, to make it more readable. Since this is an "Ebook", it can be copied to a memory stick and printed at Staples or other stores, spiral bound, or printed on your own printer making it easier to read. It can also be forwarded to family and friends. A hard copy will be sent to our class archives. In the Table of Contents, the contributors' email addresses accompany their names. This gives us an opportunity to contact some dear old friends and have an email reunion. A slide show is in the beginning, Far Above…,, and the Cornell songs can be heard in the last page of the book. They will surely jog some memories. Oh, I want to go back to the old days, the good old days on the Hill. Enjoy the read. Jack Brophy '53, BME '54 Editor Far Above Cayuga’s Waters CTRL-Click link below for slide show. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lNV4XT2cUEE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LAST NAME FIRST WED EMAIL 1 ALLEN JACK [email protected] 4 AROESTY JULIEN [email protected] 9 BARKER RANDY [email protected] 12 BERLINGHOF CHARLIE [email protected] 13 BLINDER S.M. -

Cornell University Brand Center ·

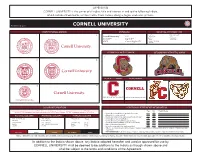

APPENDIX B CORNELL UNIVERSITY is the owner of all rights, title and interest in and to the following Indicia, which includes trademarks, service marks, trade names, designs, logos, seals and symbols. AUGUST 17, 2011 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LOCATION: ESTABLISHED DATE: 1 2 ® Cornell University C™ ITHACA, NY 1865 MASCOT: CONFERENCE: Cornell™ Big Red™ BEAR IVY LEAGUE ATHLETIC NICKNAME: CU™ Cornell Big Red™ BIG RED 7 8 3 4 9 10 11 12 5 6 Yes No Restrictions • University seal permitted on products for resale: • Alterations to seal permitted: • Overlaying / intersecting graphics permitted with seal: INSTITUTIONAL RED PANTONE 187 MADEIRA 1181 RA 2472 • University licenses consumables: BROWN PANTONE 4635 • University licenses health & beauty products: DARK BROWN PANTONE 469 MADEIRA 1145 RA 2251 • University permits numbers on products for resale: BLACK PANTONE PROCESS BLACK BLACK BLACK • Mascot caricatures permitted: WHITE WHITE WHITE WHITE • Cross licensing with other marks permitted: • NO USE of current player's name, image, or likeness is permitted on commercial products in violation of NCAA rules and regulations. • NO REFERENCES to alcohol, drugs, or tobacco related products may be used in conjunction with University marks. INST. RED WHITE BROWN DK. BROWN BLACK NOTE: The marks of Cornell University are controlled under a licensing program administered by The Collegiate Licensing Company. Any use of these marks will require written approval from The Collegiate Licensing Company. In addition to the Indicia shown above, any Indicia adopted hereafter and used or approved for use by CORNELL UNIVERSITY shall be deemed to be additions to the Indicia as though shown above and shall be subject to the terms and conditions of the Agreement.. -

How to Establish a Bequest Or Beneficiary Designation for Cornell Botanic Gardens

How to Establish a Bequest or Beneficiary Designation for Cornell Botanic Gardens STEP 1: Contact us about your gift intentions. When you name Cornell Botanic Gardens in your Will or as the beneficiary of another asset, you decide how we should use your support. Of course, an unrestricted gift or a gift to be added to our general endowment will provide the greatest flexibility to meet our future needs. We can assist you in determining how to direct your gift so that it is most meaningful for you, and provide you or your attorney with suggested language. Contact Lynn Swain (607-255-7416 or email [email protected]), if you would like to explore opportunities to support a specific place or program at the Botanic Gardens. STEP 2: Bequest: Create a new Will or trust and include a bequest for Cornell Botanic Gardens, or modify your present Will by adding a codicil. (See sample language on next page.) Beneficiary Designation: Include Cornell Botanic Gardens as a beneficiary of your retirement plan, life insurance, or investment account. Here is the information you will need: Beneficiary: Cornell Botanic Gardens, Cornell University, Federal Tax ID: 15-0532082 Mailing address: 130 E. Seneca St, Suite 400, Ithaca, NY 14850 Often, the plan documents will only allow the name and tax ID for a beneficiary organization. In that case, we typically also draft a Letter of Agreement to ensure that your future gift will be directed to the Botanic Gardens when it is realized. Call 800-481-1865 or e-mail [email protected] if you need assistance in obtaining and filling out the forms provided by your plan administrator. -

Alumni Magazine C2-C4camjf07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page C2 001-001Camjf07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1

c1-c1CAMJF07 12/22/06 1:58 PM Page c1 January/February 2007 $6.00 alumni magazine c2-c4CAMJF07 12/21/06 2:50 PM Page c2 001-001CAMJF07toc 12/21/06 1:39 PM Page 1 Contents JANUARY / FEBRUARY 2007 VOLUME 109 NUMBER 4 alumni magazine Features 52 2 From David Skorton Residence life 4 Correspondence Under the hood 8 From the Hill Remembering “Superman.” Plus: Peres lectures, seven figures for Lehman, a time capsule discovered, and a piece of Poe’s coffin. 12 Sports Small players, big win 16 Authors 40 Pynchon goes Against the Day 40 Going the Distance 35 Camps DAVID DUDLEY For three years, Cornell astronomers have been overseeing Spirit 38 Wines of the Finger Lakes and Opportunity,the plucky pair of Mars rovers that have far out- 2005 Atwater Estate Vineyards lived their expected lifespans.As the mission goes on (and on), Vidal Blanc Associate Professor Jim Bell has published Postcards from Mars,a striking collection of snapshots from the Red Planet. 58 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business 112 46 Happy Birthday, Ezra 61 Alma Matters BETH SAULNIER As the University celebrates the 200th birthday of its founder on 64 Class Notes January 11, we ask: who was Ezra Cornell? A look at the humble Quaker farm boy who suffered countless financial reversals before 104 Alumni Deaths he made his fortune in the telegraph industry—and promptly gave it away. 112 Cornelliana What’s your Ezra I.Q.? 52 Ultra Man BRAD HERZOG ’90 18 Currents Every morning at 3:30, Mike Trevino ’95 ANATOMY OF A CAMPAIGN | Aiming for $4 billion cycles a fifty-mile loop—just for practice. -

Douglas Mckee

September 2019 DOUGLAS MCKEE Department of Economics http://dougmckee.net/ Cornell University http://teachbetter.co/ 466 Uris Hall [email protected] Ithaca, NY 14853-7601 310-266-2438 CURRENT POSITION Cornell University, Department of Economics, Senior Lecturer, 2016-present Cornell University, Department of Economics, Active Learning Initiative Project Lead, 2017-present EDUCATION Ph.D., Economics, UCLA, 2006. B.S. magna cum laude, Computer Science, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, 1989. RESEARCH FIELDS Economic Education, Development Economics, Labor Economics, Health Economics GRANTS AND FELLOWSHIPS Active Learning Initiative, Cornell Economics Department Grant, 2017-2022. NIH Training Fellow, California Center for Population Research, UCLA, 2005-2006. Hewlett Foundation Fellowship for Training in International Population Studies, Summer 2005. UCLA Research Mentorship Fellowship, 2002-2003. PREVIOUS POSITIONS Yale University, Department of Economics, Senior Lecturer, 2014-2016 Yale University, Department of Economics, Associate Chair, 2012-2016 Yale University School of Medicine, RWJ/National Clinical Scholars Program, Lecturer, 2012-2016 Yale University Department of Economics, Lecturer, 2010-2014 Yale University School of Public Health, Lecturer, 2010-2012 Yale University Economic Growth Center, Post-doctoral Scholar, 2008-2010 University of Pennsylvania Population Studies Center, Post-doctoral Scholar, 2006-2008 Technical Manager and Software Developer, America Online (AOL), Dulles, VA (1995-1998) Co-founder and Software Developer, Navisoft, Santa Barbara, CA (1993-1995) Researcher and Software Developer, SRA International, VA (1989-1993) PUBLICATIONS McKee, Douglas and George Orlov. Forthcoming. “Using Invention Activities to Teach Econometrics.” Journal of Economics Teaching Green, Jeremy C., Corneliu Bolbocian, Kara Busken, Rocco Gonzalez, Douglas McKee, and Wendy Yi Xu. 2017. “Teaching Economic Evaluation with Population Health Cases.” Journal of Health Administration Education. -

Financial Plan Planning Assumptions May 2009

20 09 10 Financial Plan Planning Assumptions May 2009 Published by: The Division of Budget and Planning Cornell University 440 Day Hall Ithaca, New York 14853 http://dpb.cornell.edu/index.htm 607-255-0155 June 25, 2009 Copyright © 2009 Cornell University. All rights reserved. Additional copies of this document are available at: http://dpb.cornell.edu/FP_Current_Pubs.htm Cornell University is an equal-opportunity, affirmative-action employer and educator. 2 Planning Assumptions 3 A ACADEMIC-YEAR TUITIONS Change from Endowed Ithaca 06-07 07-08 08-09 09-10 08-09 1. Undergraduate $32,800 $34,600 $36,300 $37,750 4.0% 2. Graduate School (research degrees) 32,800 32,800 29,500 29,500 3. Graduate School (professional degrees) 32,800 34,600 36,300 37,750 4.0% 4. Hotel Administration (Mgt. Intern Pgm. – per term) 13,106 13,826 14,520 15,100 4.0% 5. Johnson School (entering MBA students) 38,800 42,700 44,950 47,150 4.9% 6. Johnson School (continuing MBA students) 38,800 40,700 44,950 46,700 3.9% 7. Johnson School (accelerated MBA program – summer) 23,800 25,000 26,400 27,700 4.9% 8. Johnson School (Cornell-Queen’s EMBA – 17 month) 92,000 95,000 98,000 99,800 1.8% 9. Johnson School (executive MBA program – two-year) 116,800 122,400 127,800 133,600 4.5% 10. Law School (entering students) 40,580 43,620 46,670 48,950 4.9% 11. Law School (2nd-year students) 39,640 42,710 45,800 48,950 6.9% 12. -

Cornell University Dept

LinkingLinking EnvironmentalEnvironmental ConditionsConditions toto ProductivityProductivity Professor Alan Hedge, PhD, CPE Cornell University Dept. Design & Environmental Analysis NYS College of Human Ecology Ithaca, NY 14853-4401 (email: [email protected]) (Abbreviated slideshow based on a presentation at the Eastern Ergonomics Conference and Exposition, New York, June, 2004) IEQIEQ EffectsEffects onon ProductivityProductivity zz ScatteredScattered studiesstudies thatthat mostlymostly showshow evidenceevidence ofof anan associationassociation betweenbetween indoorindoor environmentenvironment conditionsconditions andand somesome measuremeasure ofof performance.performance. zz ResearchResearch issues:issues: – Laboratory vs. field studies – Single vs. multiple contaminants/conditions – Surveys vs. interventions – Short-term vs. longer-term – Single exposure vs. multiple exposure – Time-lagged effects – Acute vs. chronic health effects IEQIEQ EffectsEffects onon ProductivityProductivity System Environmental Productivity Impact experience Heating, z Thermal comfort z Performance decreases when too cold Ventilating and z Indoor Air Quality z Performance decreases when too hot Air Conditioning Air Conditioning z Background noise z Performance decreases in polluted air System z Mechanical z Performance decreases when too noisy vibration z Performance decreases when z Personal person/equipment vibrates control/stress z Performance decreases with no control (perceived or real) IEQIEQ EffectsEffects onon ProductivityProductivity System Environmental