Chinese Workers at Central Pacific Railroad Section Station Camps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relative Train Length and the Infrastructure Required to Mitigate Delays from Operating Combinations of Normal and Over-Length F

Original Article Proc IMechE Part F: J Rail and Rapid Transit 0(0) 1–12 Relative train length and the ! IMechE 2018 Article reuse guidelines: infrastructure required to mitigate sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/0954409718809204 delays from operating combinations journals.sagepub.com/home/pif of normal and over-length freight trains on single-track railway lines in North America C Tyler Dick , Ivan Atanassov, F Bradford Kippen III and Darkhan Mussanov Abstract Distributed power locomotives have facilitated longer heavy-haul freight trains that improve the efficiency of railway operations. In North America, where the majority of mainlines are single track, the potential operational and economic advantages of long trains are limited by the inadequate length of many existing passing sidings (passing loops). To alleviate the challenge of operating trains that exceed the length of passing sidings, railways preserve the mainline capacity by extending passing sidings. However, industry practitioners rarely optimize the extent of infrastructure investment for the volume of over-length train traffic on a particular route. This paper investigates how different combinations of normal and over-length trains, and their relative lengths, relate to the number of siding extensions necessary to mitigate the delay performance of over-length train operation on a single-track rail corridor. The experiments used Rail Traffic Controller simulation software to determine train delay for various combinations of short and long train lengths under different directional distributions of a given daily railcar throughput volume. Simulation results suggest a relationship between the ratio of train lengths and the infrastructure expansion required to eliminate the delay introduced by operating over- length trains on the initial route. -

Railroads in Utah by Michael Huefner

Utah Social Studies Core OUR PAST, THEIR PRESENT UT Strand 2, Standard 2.5-6, 8 Teaching Utah with Primary Sources Engines of Change: Railroads in Utah By Michael Huefner Railroads Arrive in Utah, 1868-1880 About These Documents Rails to Unite America Maps: Railroad development in Utah, Well before the Civil War began, railroads had proven to be engines of Ogden, Kenilworth mining town. economic growth, westward expansion, and industrialization in America. In 1861, the northern states boasted 21,000 miles of well- Oral Histories: Interviews with people connected railroads, while the agrarian South had about 9,500. As who tell how the railroad affected their railroad lines extended from eastern hubs toward the Midwestern lives. frontier, states and towns lobbied to secure a railroad connection, Photographs: Building the competing for new settlers and businesses. Remote villages could transcontinental railroad and other rail secure future growth through a railroad, while established towns could lines, new immigrant groups, Utah towns fall into decline if they were passed by. The expansion escalated further before and after. after the 1849 California Gold Rush. Questions for Young Historians But the Civil War threatened this progress. It was at this time that the idea of a transcontinental railroad connecting California’s riches to What would it have been like to be a America’s eastern core of business gained traction. Such a railroad worker on the Transcontinental Railroad? promised to strengthen the northern economy, to symbolically unite Why were people in Utah Territory eager the country, to conquer the continent, and to dramatically reduce the to bring the railroad to Utah? time and expense of travel and shipping. -

Transcontinental Railroad Fact Sheet

Transcontinental Railroad Fact Sheet Prior to the opening of the transcontinental railroad, it took four to six months to travel 2000 miles from the Missouri River to California by wagon. January 1863 – Central Pacific Railroad breaks ground on its portion of the railroad at Sacramento, California; the first rail is laid in October 1863. December 1863 – Union Pacific Railroad breaks ground on its portion of the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska; due to the Civil War, the first rail is not laid until July 1865. April 1868 – the Union Pacific reaches its highest altitude 8,242 feet above sea level at Sherman Pass, Wyoming. April 28, 1869 – a record of 10 miles of track were laid in a single day by the Central Pacific crews. May 10, 1869 – the last rail is laid in the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Point, Utah. Total miles of track laid 1,776: 690 miles by the Central Pacific and 1086 by the Union Pacific. The Central Pacific Railroad blasted a total of 15 tunnels through the Sierra Nevada Mountains. It took Chinese workers on the Central Pacific fifteen months to drill and blast through 1,659 ft of rock to complete the Summit Tunnel at Donner Pass in Sierra Nevada Mountains. Summit Tunnel is the highest point on the Central Pacific track. The Central Pacific built 40 miles of snow sheds to keep blizzards from blocking the tracks. To meet their manpower needs, both railroads employed immigrants to lay the track and blast the tunnels. The Central Pacific hired more than 13,000 Chinese laborers and Union Pacific employed 8,000 Irish, German, and Italian laborers. -

C&O Has Good Ideas In

Siding thrown over to locate main track signal between main and siding C & 0 Has Good Ideas in CTC Sheet-metal houses not only at switches but also at interme diate signals and use of hold-out signals are features of this project. Well organized construction requires no work trains. TO INCREASE TRACK CAPAC portant freight line. Numerous Windsor, Ont., and Blenheim, Ont. ITY, facilitate train movements industries , including large, automo Previously no signaling was in and reduce operating expenses, the bile factories, are located at Plym service on the single track between Chesapeake & Ohio has installed outh , Flint and Saginaw. Also the Plymouth and Kearsley interlock centralized traffic control on 55 Plymouth-Saginaw section is part ing at Flint. Two tracks extend miles of single-track between Plym of an important route to and from north from Plymouth 1.0 mile to a outh, Mich., and Mount Morris, Ludington, Mich., which is the port power switch which is included in Mich. This project connects with for C&O car ferries, operated all the new CTC. At Wixom there are CTC previously in service on 24 year, across Lake Michigan to and two sidings with power switches miles between Mt. Morris and from Wisconsin ports of Milwau included in the CTC. Other sidings Saginaw, Mich., the entire 79 miles kee, Manitowoc and Kewaunee. with power switches included in between Plymouth and Saginaw the CTC are at Clyde and Newark. now being controlled from a ma Twenty Trains Dally These sidings were lengthened to chine at Saginaw. hold 112 and 133 cars respectively . -

Landscape Medallion in Washington State

Architect of the Capitol Landscape medallion (detail), Brumidi Corridors. Brumidi’s landscape medallions relate to the federally sponsored Pacific Railroad Report and depict scenes from the American West, such as this view of Mount Baker in Washington State. The “MostBrumidi’s Landscapes andPracticable the Transcontinental Railroad ”Route Amy Elizabeth Burton or 150 years, senators, dignitaries, and visitors to the U.S. Capitol have bustled past 8 Flandscape medallions prominently located in the reception area of the Brumidi Corridors on the first floor of the Senate wing. For most of this time, very little was understood about these scenes of rivers and mountains. The locations depicted in the landscapes and any relevance the paintings once held had long faded from memory. The art of the Capitol is deeply rooted in symbolism and themes that reflect national pride, which strongly suggested that the medallions’ significance extended beyond their decorative value. Ultimately, a breakthrough in scholarship identified the long-forgotten source of the eight landscapes and reconnected them to their his- torical context: a young nation exploring and uniting a vast continent, as well as a great national issue that was part of this American narrative—the first transcontinental railroad. THE “MOST PRACTICABLE” ROUTE 53 Starting in 1857, the Brumidi Corridors in the newly con- From roughly 1857 to 1861, Brumidi and his team structed Senate wing of the Capitol buzzed with artistic of artists decorated the expansive Brumidi Corridors activity. Development of the mural designs for the Sen- with Brumidi’s designs, while one floor above, the Senate ate’s lobbies and halls fell to artist Constantino Brumidi, deliberated about the building of the nation’s first trans- under the watchful eye of Montgomery C. -

Derails in Passing Sidings? As 1.5 U 'Ually the Case, It I'> Impo%Ible to Move Tre Insulated Ioiflt

30 RAILWAY SIGNALING Vol. 24, No.1 i\s the InSUlltld joint i" a :,ecessary part aT the 19nal ( ,,) In torcing rat elK~ - 1)art use a ratl expander It system as well as 0" the t'c.ck, it mturally follows tl1dt It one IS &t haIld DC! not use an )rdinary full tap"'r '"rack belongs neither to one department nor to the other, but chise1. If a chisel muq be usen, use on(; whICh is wider to both, Therefore, both departments should interest th,l11 the rail-head and which has a small japer, 111 order themselves 111 hcping 'nsulated joil'ts in repair in an to 1\ aid d~.ma2ing the rail el d. efficient and er ollomin1 mannu, (0 Do It bend 'lOlts or drive them through btl ~h;ngs. 11o:t men who are ell cdl} responsible for the care If rail end~ a d ;oir,t parts Ir in prope' POSI io 1, he of JO'nts ha\ e found that mp1 r defects, which req~lre bn]ts can be l11::-e ted w thO'lt rr...lt1:'n", n' bending. very little til e to remedy, such a" loose r,ub. lipped (7) Paler 1 .suL i II W 11 nN 'dthstand the erorl"ous rail tnds, rail fins cutting mto 5.11er, low or loose ties fon (' of rail expansion in hot weather. After the proper and defeclive spikl11g, should be corrected Immediately OpUlIllg IS secured between the rail cnus for the ll1 ertion upon being detected a £ the end post: it should be held, a::: much as pOSSIble, Frequent inspection shuuld be made, SIgnal mail by the installatlOl1 of ~ail ancile r5. -

Railway Siding Rules and Regulations

Appendix no. 2 – Characteristics of railway siding infrastructure elements (excerpt) RAILWAY SIDING RULES AND REGULATIONS: CENTRUM LOGISTYCZNO INWESTYCYJNE POZNAŃ II SPÓŁKA Z OGRANICZONĄ ODPOWIEDZIALNOŚCIĄ 62-020 SWARZĘDZ - JASIN, UL. RABOWICKA 6, Valid from 1st November 2017 1 1. Technical description of railway siding: 2.1. Location of railway siding: Centrum Logistyczno Inwestycyjne Poznań II sp. z o.o. siding is a station siding with branching turnout no. 6 to station track no. 6b of Swarzędz station at km 291.017 of railway line no. 003 Warsaw West - Kunowice (for the siding it is km 0.000 - beginning of turnout no. 6 is the beginning of the siding track). 2.2. Switch circles and traffic operation positions and their manning: CLIP II Railway siding constitutes five manoeuvring zones. No traffic operation position and manning on the siding. 2.3. Location of delivery-acceptance points at the siding: 1) The acceptance track for wagons, groups of wagons and full train sets brought by the Carrier is track no. 101 or track no. 105 of the siding CENTRUM LOGISTYCZNO INWESTYCYJNE POZNAŃ II. 2) The delivery track for wagons, groups of wagons and full train sets brought by the Carrier is track no. 101 or track no. 103 of the siding CENTRUM LOGISTYCZNO INWESTYCYJNEGO POZNAŃ II. 3) On site, the delivery-acceptance point is marked with a sign “Delivery-acceptance point”, the sign is located at the intertrack space of tracks 101 and 103. 2.4. Tracks on siding: General length of track Usable length of track Capacity - Notes (‰) section section Purpose Track no. -

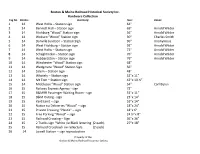

Station Sign 64” 2 14 Bennet

Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 1 14 West Hollis – Station sign 64” 2 14 Bennett Hall – Station sign 69” Arnold Wilder 3 14 Fitchburg “Wood” Station sign 56” Arnold Wilder 4 14 Woburn “Wood” Station sign 30” Charles Smith 5 14 Danville Junction – Station Sign 96” Anonymous 6 14 West Fitchburg – Station sign 92” Arnold Wilder 7 14 West Hollis – Station sign 72” Arnold Wilder 8 14 Scheghticoke – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 9 14 Hubbardston – Station sign 76” Arnold Wilder 10 14 Winchester “Wood” Station sign 68” 11 14 Wedgmere “Wood” Station Sign 56” 12 14 Salem – Station sign 48” 13 14 Whately – Station sign 52”x 11” 14 14 Mt Tom – Station sign 42”x 10 ½” 15 14 Middlesex “Wood” Station sign 54” Carl Byron 16 15 Railway Express Agency - sign 72” 17 15 B&MRR Passenger Waiting Room - sign 32”x 11” 18 15 B&M Outing - sign 23”x 14” 19 15 Yard Limit – sign 16”x 14” 20 15 Notice no Deliveries “Wood” – sign 18”x 24” 21 15 Private Crossing “Plastic” – sign 18”x 6” 22 15 Free Parking “Wood” – sign 24 ½”x 8” 23 15 Railroad Crossing – Sign 36”x 36” 24 15 2 Tracks sign “White /w Black lettering (2 each) 27”x 18” 25 15 Railroad Crossbuck /w reflectors (2 each) 26 14 Lowell Station – sign reproduction Property of the Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Boston & Maine Railroad Historical Society Inc. Hardware Collection Tag No. File No: Inventory: Size: Donor: 27 15 Hand Held Stop – sign Donald S. -

Race to Promontory

This resource, developed by the Union Pacific Railroad Museum, is a comprehensive guide for telling the story of the first American transcontinental railroad. In addition to bringing to life this important achievement in American history, this kit allows students to examine firsthand historical photographs from the Union Pacific collection. This rare collection provides a glimpse into the world of the 1860s and the construction of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. Today, nearly everything American families and businesses depend on is still carried on trains – raw materials such as lumber and steel to construct homes and buildings; chemicals to fight fires and improve gas mileage; coal that generates more than half of our country’s electricity needs; produce and grain for America’s food supply; and even finished goods such as automobiles and TVs. After 150 years, UP now serves a global economy and more than 7,300 communities across 23 states. National Standards for History • Grades 3-4 5A.1 & 8.B. 4 & 6 www.nchs.ucla.edu/history-standards/standards-for-grades-k-4/standards-for-grades-k-4 National Center for History in Schools • Grades 5-12 Era 4 Expansion and Reform (1801-1861). 4A.2.1-3, 4E.1 & 4 www.nchs.ucla.edu/history-standards/us-history-content-standards National Center for History in Schools Additional Resources • Bain, David Haward. Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad. New York: Penguin, 2000. Print. • The Union Pacific Railroad Museum’s official website. www.uprrmuseum.org • Union Pacific’s official website. www.up.com • The Golden Spike National Historic Monument. -

Transcontential Railroad Time Table

USHistoryAtlas.com Primary Sources Transcontential Railroad Time Table Date # February 1881 Place # Boston, Massachusetts, Omaha, Nebraska, and San Francisco, California Type of Source # Daily Life Author # Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads Context # The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 allowed relatively rapid transportation across the United States. By 1881 thousands of people were using railroads to reach new homes in the West, as well as conduct business across the country and ship goods. Passengers could travel from Omaha to San Francisco, almost 1900 miles, in less than a week for between $45 to $100 (about $950 to $2100 in present dollars). Railroads would prove essential to the development of the West. Stations on Union Pacific Line Through Line Through Line (East to West) This line connected with IOWA: the Central Pacific at Council Bluffs Ogden and was used to NEBRASKA: Omaha, Summit Siding, Papillion, Millard, Elkhorn, Waterloo, cross the country. Valley, Riverside, Fremont, Ames, North Bend, Rogers, Schuyker, Benton, Ogden, Utah Columbus, Duncan, Silver Creek, Clark’s, Central City, Chapman’s, Grand Ogden was the nearest city to Promintory Point, where Island, Alda, Wood River, Shelton, Gibbon, Buda, Kearney Junction, Stevenson, the two railroads were first Elm Creek, Overton, Josselyn, Plum Creek, Cozad, Willow Island, Warren, Brady joined. Its station was Island, Maxwell, Gannett, North Platte, O’Fallon’s, Dexter, Alkali, Roscoe, made the meeting point for Ogalalla, Big Springs, Barton, Julesburg, -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and distric s Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each it< ering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architecture classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_______________________________________________ historic name: Toana Freight Wagon Road Historic District________________ other name/site number: Toana Road __ 2. Location street & number Generally run south to north from Nevada-Idaho stateline to the Snake River [ ] not for publication city or town Castleford___________________________________ [ X ] vicinity state: Idaho code: ID county: Twin Falls code: 083 zip code: 83321 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [X ] meets [ Idoes not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] natioparfly [ ] statewid<£[ X ] lopertrv^fTT^ee continuation sheet for additional comments.] Signature of certifying official/Title - Date State or Federal agency and bureau \r\ my opinion, the property yQ meets [ ] does not meet the National ([ ] See continuation sheet for additional comments). -

Minnesota Statewide Historic Railroads Study Final MPDF

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) Expires 12-31-2005 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section: F Page 183 Railroads in Minnesota, 1862-1956 Name of Property Minnesota, Statewide County and State Section F. Associated Property Types I. Name of Property Type: Railroad Corridor Historic Districts II. Description The property type “railroad corridor historic district” encompasses the right of way within which a railroad operated and all of the buildings, structures, and objects that worked together for the dedicated purpose of running trains to transport freight and passengers. The elements of railroad corridor historic districts are organized within linear rights of way that range from approximately 30 feet to several hundred feet in width but may extend for hundreds of miles in length. The linear nature of the railroad corridor historic district is an important associative characteristic that conveys the sense of a train traveling to a destination (Figure 1; Note: all figures are located at the end of Section F). The MPDF Railroads in Minnesota, 1862-1956 does not distinguish between railroad mainlines and branch lines. Although, historically, railroad companies identified their railroad corridors as mainlines or branch lines, the definition of mainline varied from company to company, depending on volume of freight, priority on operations time tables, and other factors. In addition, a railroad corridor’s status may have changed over time, depending on operating conditions. For the purposes of evaluating historic significance, a railroad corridor’s status as mainline or branch line is not a determinant; a railroad corridor can be eligible for the National Register regardless of its status as a mainline or branch line.