Notes on Colours and Pigments in the Ancient World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45110 Ultramarine Violet, Reddish

45110 Ultramarine Violet, reddish Product name: Ultramarine Violet, reddish Chemical name: Sodium-aluminium-sulfo-silicate Color index: C.I. Pigment violet 15 : 77007 C.A.S. No.: 12769-96-9 EINECS No.: 2-358-110 Specification: Color shade DE CIEL (max): 1.00 lightening 1:5,4 with TiO2 in impact-resistant polystyrene Coloring strength (compared to standard): ± 5 % Oversize (45 µm): max. 0.05 % Volatile moiety (105°C): max. 1.30 % Free sulfur: max. 0.05 % Water soluble parts: max. 1.00 % Typical Data: Color grade: 49 Density: 2.35 Bunk density (g/cm 3) 0.63 Oil adsorption: 34.5 Middle particle size (µm): 1.85 Fastness/Resistance Temperature resistance: > 260°C Light fastness (full color): excellent (7 - 8) Light fastness (lightening): excellent (7 - 8) Alkali resistance: excellent Acid resistance: weak Safety Information Acute oral toxicity (LD50, rat): > 10 g/kg Skin irritation: not irritant and not sensitizing Eye irritation: not irritant Exposition limit: 6 mg/m 3 (MAK Value) Ecology: not hazardous Regulations Ultramarine violet is a non toxic pigment. It is universally authorized as coloring agent for objects being in contact with food and for the manufacture of toys. Storage, Stability and Handling Transportation and storage: Do not store near acid substances. Non-compatible substances: Acids. Decomposition products: Hydrogen sulfide is released after contact with acids. Special protective measures: None, however, avoid contact with excessive dust. Special measures in case of release: Clean-up immediately. Avoid spilling of large amounts of dust. Dispose of spilled material in accordance with local and national regulations. Page 1 of 1 Kremer Pigmente GmbH & Co. -

Tucson Art Academy Online Skip Whitcomb

TUCSON ART ACADEMY ONLINE SKIP WHITCOMB PAINTS WHITE Any good to professional quality Titanium or Titanium/Zinc White in large tubes(150-200ML) size. Jack Richeson Co., Gamblin, Vasari, Utrecht, Winsor & Newton are all good brands, as are several other European manufacturers. I strongly recommend staying away from student grade paints, they do not mix or handle the same as higher/professional grade paints. YELLOWS Cadmium Yellow Lemon Cadmium Yellow Lt. (warm) Cad. Yellow Medium or Deep Indian Yellow ORANGES Cadmium Yellow Orange (optional) Cadmium Orange REDS Cadmium Red Light/ Pale/ Scarlet (warm) Cadmium Red Deep Permanent Alizarin Crimson Permanent Rose (Quinacridone) BLUES Ultramarine Blue Deep or Dark Cobalt Blue Prussian Blue or Phthalo Blue GREENS Viridian Viridian Hue (Phthalo Green) Chrome Oxide Green Olive Green Sap Green Yellow Green VIOLETS Mauve Blue Shade (Winsor&Newton) Dioxazine Violet or Purple EARTH COLORS Yellow Ochre Raw Sienna Raw Umber Burnt Sienna Terra Rosa Indian Red Venetian Red Burnt Umber Van Dyke Brown BLACKS Ivory Black Mars Black Chromatic Black Blue Black MARS COLORS Mars Yellow Mars Orange Mars Red Mars Violet IMPORTANT TO NOTE!! Please don’t be intimidated by this list! You will not be required to have all these colors on hand for our class. This is intended to be a recommendation for the studio. Specific colors on this list will come in handy for mixing in certain color plans. I will be happy to make suggestions along the way A good working palette for the studio would be: Cad. Yellow Lemon, Cad. Yellow Pale(warm), and/or Cad. -

Pale Intrusions Into Blue: the Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Pale Intrusions into Blue: The Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE PALE INTRUSIONS INTO BLUE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A COLOR By HANNAH ROSE MENDOZA A Thesis submitted to the Department of Interior Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Hannah Rose Mendoza defended on October 21, 2004. _________________________ Lisa Waxman Professor Directing Thesis _________________________ Peter Munton Committee Member _________________________ Ricardo Navarro Committee Member Approved: ______________________________________ Eric Wiedegreen, Chair, Department of Interior Design ______________________________________ Sally Mcrorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts & Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Pepe, te amo y gracias. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my gratitude to Lisa Waxman for her unflagging enthusiasm and sharp attention to detail. I also wish to thank the other members of my committee, Peter Munton and Rick Navarro for taking the time to read my thesis and offer a very helpful critique. I want to acknowledge the support received from my Mom and Dad, whose faith in me helped me get through this. Finally, I want to thank my son Jack, who despite being born as my thesis was nearing completion, saw fit to spit up on the manuscript only once. -

Ultramarine Blue

SAFETY DATA SHEET According to OSHA 29 CFR 1910.1200 – GHS Revision date: September 7, 2015 Supersedes: November 13, 2014 ULTRAMARINE BLUE 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product name: Ultramarine Blue, Nubix, Nubiperf, Nubiflow, Nubicoat HRD, Nubicoat HTS, Nubicoat HWR Victoria Ultramarine Blue Use: Coloring agents, Pigments Company identification: NUBIOLA USA 6369 Peachtree Street Norcross, GA 30071, USA Tel +1 (770) 277-8819 [email protected] Emergency telephone number: 800-424-9300 (CHEMTREC, 24 hours) International call: 703-527-3887 (collect calls accepted) 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION Classification of the chemical in accordance with Standard 29 CFR 1910.1200 (US-GHS) Not classified. Label elements (Hazard Communication Standard 29 CFR 1910.1200 (US-GHS) No labelling applicable. 3. COMPOSITION / INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Chemical name CAS No Concentration (%) RTECS No Ultramarine Blue 57455-37-5 100 --- (Pigment Blue 29, CI 77007) Substance / Mixture: Substance Synonyms: Blue sodium polysulfide aluminosilicate sodalite-type 4. FIRST-AID MEASURES Description of first-aid measures In case of inhalation: If breathing is difficult, remove to fresh air and keep at rest in a position comfortable for breathing. If you feel unwell, seek medical attention. In case of skin contact: Rinse skin with water. If skin irritation occurs, get medical advice. In case of eye contact: Immediately flush eyes with plenty of water for at least 15 minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rising. If eye irritation occurs, get medical advice. In case of ingestion: Rinse mouth. Do not induce vomiting unless directed to do so by a physician. If you feel unwell, seek medical attention. -

Manufacturer of the World's Finest Artists' Paints

Manufacturer of the World’s Finest Artists’ Paints MADE IN THE USA SINCE 1976 Meet the Owner of DANIEL SMITH John Cogley John Cogley, the owner of DANIEL SMITH Artists’ Materials, joined the company in the Information Technology Department in 1988. With almost three decades of leading the company as President, CEO and Owner, John has been the driving force behind making DANIEL SMITH Watercolors and other products recognized as the world’s best. Because of John’s commitment to innovation and in manufacturing the highest quality paints and other products, artists worldwide can rely on the performance and continuity of DANIEL SMITH products year after year. DANIEL SMITH is the Innovative Sticks, artist-quality Water Soluble Oils Manufacturer of Beautiful Watercolors and inspiring Hand Poured Half Pan sets and Oils for Artists Worldwide. DANIEL SMITH has been the leader in From being the first manufacturer developing creative tools for Artists. to make the high-performance Making beautiful, innovative, and high Quinacridone pigments into artists’ quality artists paints, which perform paints, to the development of the exciting consistently from tube to tube, year after PrimaTek and Luminescent Watercolors year, makes DANIEL SMITH products the and Oils, Watercolor Grounds, Watercolor choice for artists worldwide. Stay connected with DANIEL SMITH online! INSTAGRAM FACEBOOK @danielsmithartistsmaterials @DanielSmithArtSupplies REGIONAL ACCOUNTS REGIONAL ACCOUNTS ASIA ASIA @danielsmithasia @Danielsmithartsupplies_asia EUROPE EUROPE @danielsmitheurope -

Gamblin Provides Is the Desire to Help Painters Choose the Materials That Best Support Their Own Artistic Intentions

AUGUST 2008 Mineral and Modern Pigments: Painters' Access to Color At the heart of all of the technical information that Gamblin provides is the desire to help painters choose the materials that best support their own artistic intentions. After all, when a painting is complete, all of the intention, thought, and feeling that went into creating the work exist solely in the materials. This issue of Studio Notes looks at Gamblin's organization of their color palette and the division of mineral and modern colors. This visual division of mineral and modern colors is unique in the art material industry, and it gives painters an insight into the makeup of pigments from which these colors are derived, as well as some practical information to help painters create their own personal color palettes. So, without further ado, let's take a look at the Gamblin Artists Grade Color Chart: The Mineral side of the color chart includes those colors made from inorganic pigments from earth and metals. These include earth colors such as Burnt Sienna and Yellow Ochre, as well as those metal-based colors such as Cadmium Yellows and Reds and Cobalt Blue, Green, and Violet. The Modern side of the color chart is comprised of colors made from modern "organic" pigments, which have a molecular structure based on carbon. These include the "tongue- twisting" color names like Quinacridone, Phthalocyanine, and Dioxazine. These two groups of colors have unique mixing characteristics, so this organization helps painters choose an appropriate palette for their artistic intentions. Eras of Pigment History This organization of the Gamblin chart can be broken down a bit further by giving it some historical perspective based on the three main eras of pigment history – Classical, Impressionist, and Modern. -

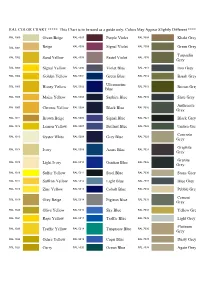

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart Is to Be Used As a Guide Only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** Green Beige Purple V

RAL COLOR CHART ***** This Chart is to be used as a guide only. Colors May Appear Slightly Different ***** RAL 1000 Green Beige RAL 4007 Purple Violet RAL 7008 Khaki Grey RAL 4008 RAL 7009 RAL 1001 Beige Signal Violet Green Grey Tarpaulin RAL 1002 Sand Yellow RAL 4009 Pastel Violet RAL 7010 Grey RAL 1003 Signal Yellow RAL 5000 Violet Blue RAL 7011 Iron Grey RAL 1004 Golden Yellow RAL 5001 Green Blue RAL 7012 Basalt Grey Ultramarine RAL 1005 Honey Yellow RAL 5002 RAL 7013 Brown Grey Blue RAL 1006 Maize Yellow RAL 5003 Saphire Blue RAL 7015 Slate Grey Anthracite RAL 1007 Chrome Yellow RAL 5004 Black Blue RAL 7016 Grey RAL 1011 Brown Beige RAL 5005 Signal Blue RAL 7021 Black Grey RAL 1012 Lemon Yellow RAL 5007 Brillant Blue RAL 7022 Umbra Grey Concrete RAL 1013 Oyster White RAL 5008 Grey Blue RAL 7023 Grey Graphite RAL 1014 Ivory RAL 5009 Azure Blue RAL 7024 Grey Granite RAL 1015 Light Ivory RAL 5010 Gentian Blue RAL 7026 Grey RAL 1016 Sulfer Yellow RAL 5011 Steel Blue RAL 7030 Stone Grey RAL 1017 Saffron Yellow RAL 5012 Light Blue RAL 7031 Blue Grey RAL 1018 Zinc Yellow RAL 5013 Cobolt Blue RAL 7032 Pebble Grey Cement RAL 1019 Grey Beige RAL 5014 Pigieon Blue RAL 7033 Grey RAL 1020 Olive Yellow RAL 5015 Sky Blue RAL 7034 Yellow Grey RAL 1021 Rape Yellow RAL 5017 Traffic Blue RAL 7035 Light Grey Platinum RAL 1023 Traffic Yellow RAL 5018 Turquiose Blue RAL 7036 Grey RAL 1024 Ochre Yellow RAL 5019 Capri Blue RAL 7037 Dusty Grey RAL 1027 Curry RAL 5020 Ocean Blue RAL 7038 Agate Grey RAL 1028 Melon Yellow RAL 5021 Water Blue RAL 7039 Quartz Grey -

Gelest Launches Ultramarine Pink and Violet Pigments

May 5, 2021 For Immediate Release Gelest Launches Ultramarine Pink and Ultramarine Violet Surface Treated Pigments New colors extend Ultramarine line, expand Gelest personal care offering. Gelest, Inc. MORRISVILLE, Pa., May 5, 2021 – Gelest, Inc. today launched Ultramarine Pink and Ultramarine Violet surface treated pigments, broadening its ultramarine line and enhancing its personal care offerings. Along with Gelest’s Ultramarine Blue, the new surface-treated ultramarine pigments create clean, bright shades to soft pastels in eye makeup and powders. The surface treatments increase durability, lower oil absorption, improve skin adhesion, enhance water repellency and facilitate dispersion processing in formulations. “We are launching the ultramarines as part of our continuing commitment to the cosmetic pigments market and to enhance our product offering to customers,” said Daria Long, Gelest Vice President and General Manager, Personal Care. “We’ve seen a resurgence in pink and violet eyeshadows, so we added these new ultramarines to help cosmetics formulators respond to the increased demand.” Long added that given mask-wearing due to COVID-19, people are focusing on their eyes and looking for non-traditional makeup options. The new ultramarines help make unconventional looks possible. Gelest selected three hydrophobic surface treatments that deliver the most benefit in eye makeup, where ultramarine pigments see the most use. The ultramarines are available with the Trimethylsiloxysilicate (SR), Stearyl Triethoxysilane (SS) and Triethoxycaprylylsilane (TC) surface treatments. “We recommend the SR treatment for mascaras, eyeliners and especially for powders to prevent sebum breakthrough and decrease creasing on eyelids,” said Long. “The SR treatment contains a film former that increases water resistance and improves skin adhesion -- leading to better wear over time.” She suggests the SS treatment for improved powder feel, longer wear and increased hydrophobicity; and the TC treatment for its economic and hydrophobic attributes. -

Blue, Violet and Pink Pigments ULTRAMARINE

ULTRAMARINE Blue, violet and pink pigments 9:1 in titanium dioxide 1:3 9:1 1:3 PREMIER XSG PREMIER XAR PREMIER GS PREMIER VSB PREMIER XSR PREMIER VSR PREMIER RX PREMIER PX PREMIER RS PREMIER RM Ultramarine blue, violet and pink pigments. Clean, bright, easy dispersing inorganic pigments offering unique and attractive colors, high transparency and excellent heat stability and lightfastness. Color reproduction: For technical reasons connected with color reproduction, the colors shown may not exactly match the pigment colors and do not represent a particular finish. www.venatorcorp.com ULTRAMARINE Blue, violet and pink pigments Color Index Description PB29, PV15, PR259 CI Number 77007 Chemical Description Silicic acid, aluminium sodium salt, sulfurized Particle Shape Spheroidal Product Typical Properties E Thermal (°C)** Resistance Oil Absorption (g/100g) Specific Gravity Lightfastness wool scale) (blue Acid / Alkali Resistance Product Ref (C.I) Color Index Particle Average (µm)* Size Salts (%) Soluble Sulfur (%) Free Moisture (%) Residue Sieve 45µm (%) △ PREMIER XSG PB29 1.11 <0.75 <0.02 <1.50 <0.02 <0.50 350 38.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER GS PB29 1.32 <0.75 <0.02 <1.50 <0.02 <0.50 350 37.5 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER XSR PB29 1.01 <0.75 <0.02 <1.50 <0.02 <0.50 350 37.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER RX PB29 1.17 <0.75 <0.02 <1.50 <0.02 <0.50 350 35.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER RS PB29 1.63 <0.70 <0.02 <1.75 <0.02 <0.50 350 32.5 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER RM PB29 2.08 <0.70 <0.02 <0.75 <0.02 <0.50 350 33.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER XAR PB29 2.48 <0.75 <0.02 <1.50 <0.05 <0.50 350 56.0 2.30 7-8 Excellent/Excellent PREMIER VSB PV15 1.60 <0.75 <0.02 <1.00 <0.02 <1.00 260 35.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER VSR PV15 1.60 <0.75 <0.02 <1.00 <0.02 <1.00 260 35.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent PREMIER PX PR259 1.70 <1.00 <0.05 <1.50 <0.10 <1.00 220 33.0 2.35 7-8 Poor/Excellent * Venator test method LA-CP.27 using a laser particle size analyzer. -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Colour of Emotions

Colour of Emotions Utilizing The Psychology of Color GRA 3508 - Desktop Publishing II Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................... 2 Psychology of Logos ............................................................... 3 Reds ....................................................................................... 4 Overview of Red,Mauve, Magenta ............................................... 4 Crimson, Scarlet, Poster Red ...................................................... 5 Yellows................................................................................... 6 Overview of Yellow, Coral, Orange ............................................... 6 Amber, Gold, Yellow ................................................................. 7 Greens ................................................................................... 8 Overview of Green, Lime, Leaf Green .......................................... 8 Sea Green, Emerald, Teal .......................................................... 9 Blues ..................................................................................... 10 Overview of Blue, Cyan, Sky Blue ............................................... 10 Ultramarine, Violet, Purple ......................................................... 11 Credits.................................................................................... 12 1 Introduction Psychology of Logos Color is a magical element that gives feeling and emotion to art and design. It is an exclusive -

Ö and Manganese (Mn) Historically Modern

Product information resin-oil colours MUSSINI® - finest artists´ resin-oil colours Lapis lazuli and YInMn Blue - In search of the special blue Artists today are in the fortunate position of having a wide range of colours to choose from and with which they often have painted for years. But wouldn't it also be nice to try something completely new, unique, something that did not exist before or that is so rare that you can hardly find it? With the two limited special colours "Lapis lazuli" and "YInMn Blue" from the MUSSINI® series, Schmincke offers oil painters exclusively two blue colours which could not be more special and different in their origin. The highly lightfast colours are based on very special pigments, are manufactured exclusively on a historical stone mill and have the following characteristics: Lapis lazuli (10 488) YInMn Blue (10 499) Inorganic Organic Rare expensive elements Semi-precious stone "Lapis lazuli" Base Yttrium (Y), Indium (In) Ö and Manganese (Mn) Historically Modern Used since the 11th century History Discovered in 2009 Limited resources (Chile/Afghanistan),Ö Very complex probably therefore last pigment pigment production delivery Semi-transparent Optics Opaque Brilliant Ö Highly brilliant Similar to ultramarine Slightly more reddish than ultramarine H. Schmincke & Co. GmbH & Co. KG · Otto-Hahn-Str. 2 · D- 40699 Erkrath · Tel.: +49-211-2509-0 · www.schmincke.de · [email protected] 11/2020 Product information resin-oil colours So, if you are looking for that special blue and want to create a unique painting experience, these two limited MUSSINI® colours Lapis lazuli and YInMn blue are just right for you! Available in 15 ml special edition tubes.