The Cretaceous of the Swiss Jura Mountains: an Improved Lithostratigraphic Scheme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communauté De Brigades De Besançon-Tarragnoz Communauté De Brigades D'école-Valentin Communauté De Brigades D'ornans Commun

MINISTÈRE DE L'INTÉRIEUR, RÉGION DE GENDARMERIE Groupement de gendarmerie départementale du Doubs DE BOURGOGNE FRANCHE-COMTÉ Compagnie de gendarmerie départementale de Besançon Brigade territoriale autonome de Baume-les-Dames 03 81 84 11 17 / 06 15 58 59 78 1 PROMENADE DU BREUIL 25110 BAUME LES DAMES Lundi au Samedi : 8h00-12h00 14h00-19h00 Dimanche & Jour Fériés : 9h00-12h00 15h00-19h00 Communauté de brigades de Besançon-Tarragnoz Brigade de proximité de Besançon-Tarragnoz Brigade de proximité de Bouclans 03 81 81 32 23 03 81 55 20 07 39 RUE CHARLES NODIER 26 GRANDE RUE 25031 BESANCON CEDEX 25360 BOUCLANS Samedi : 8h00-12h00 14h00-18h00 Lundi au Vendredi : 8h00-12h00 14h00-18h00 Dimanche & Jours Fériés : 9h00-12h00 15h00-18h00 Communauté de brigades d'École-Valentin Brigade de proximité d'École-Valentin Brigade de proximité de Recologne 03 81 21 16 60 03 81 58 10 58 1 RUE DES TILLEULS VALENTIN 1 GRANDE RUE 25480 ECOLE VALENTIN 25170 RECOLOGNE Lundi au Samedi : 8h00-12h00 14h00-18h00 Dimanche & Jours Fériés : 9h00-12h00 15h00-18h00 Mercredi : 14h00-18h00 Communauté de brigades d'Ornans Brigade de proximité d'Ornans Brigade de proximité d'Amancey 03 81 62 21 17 03 81 86 60 60 7 RUE EDOUARD BASTIDE 14 GRANDE RUE 25290 ORNANS 25330 AMANCEY Lundi au Samedi : 8h00-12h00 14h00-19h00 Dimanche & Jours Fériés : 9h00-12h00 15h00-19h00 Mardi : 14h00-18h00 Communauté de brigades de Roulans Brigade de proximité de Roulans Brigade de proximité de Marchaux-Chaudefontaine 03 81 55 51 80 / 06 15 58 57 34 03 81 57 91 45 11 CHEMIN DE LA COMTESSE 1 RUE CHAMPONOT -

Cat 2020.Indd

CATALOGUE DE GRAINES Lausanne & Pont-de-Nant (Suisse) Index Seminum 2020 Jardins botaniques cantonaux +41 21 316 99 88 Avenue de Cour 14 bis 1007 Lausanne [email protected] Suisse www.botanique.vd.ch Contenu - Content 1. Graines récoltées au Jardin botanique de Lausanne Seeds collected at the Botanical Garden of Lausanne 2. Graines récoltées au Jardin alpin «La Thomasia», Pont-de-Nant, Les Plans-sur-Bex Seeds collected at the Alpine Garden «La Thomasia», Pont-de-Nant, Les Plans-sur-Bex 3. Graines récoltées en nature en Suisse, principalement dans le canton de Vaud Seeds collected in nature in Switzerland, mainly in the canton of Vaud 1. Graines récoltées au Jardin botanique de Lausanne Seeds collected at the Botanical Garden of Lausanne Asteraceae - suite Amaryllidaceae Echinacea Allium 016 - purpurea (L.) Moench XX-0-LAU-70122 001 - carinatum subsp. pulchellum Bonnier & Layens Grindelia CH-0-LAU-216224 017 - robusta Nutt. XX-0-LAU-70154 Apiaceae Hieracium 018 - tomentosum L. XX-0-LAU-215002 Angelica Hypochaeris 002 - archangelica L. XX-0-LAU-70029 019 - maculata L. AT-0-GZU-14 149 Levisticum Santolina 003 - offi cinale W. D. J. Koch XX-0-LAU-70182 020 - chamaecyparissus L. XX-0-LAU-70292 Myrrhis Serratula 004 - odorata (L.) Scop. CH-0-LAU- PdN 213187 ex: CH, VD, Alpes vaudoises, Pointes des Savolaires 021 - tinctoria L. s.str. CH-0-LAU-218097 005 - odorata (L.) Scop. XX-0-LAU-70213 Silybum Oenanthe 022 - marianum (L.) Gaertn. XX-0-LAU-70308 006 - fi stulosa L. XX-0-LAU-220435 Staehelina Peucedanum 023 - unifl osculosa Sibth. -

Holiday Apartements and Guest Rooms VALLORBE-ORBE-ROMAINMÔTIER

List of accomodation "Yverdon-les-Bains Région" holiday apartements and guest rooms VALLORBE-ORBE-ROMAINMÔTIER Rapin Susanne Tel.: + 41 (0)24 441 62 20 Guest suite "La Belle Etoile" Mobile: + 41 (0)79 754 22 54 The opportunity to live like a lord in this castle dating from the XII century. The Rue du Château 7 e-mail [email protected] guest suite is spacious, luxurious and bright. Château de Montcherand www.lechateau.ch 1354 Montcherand Guest suite - 2 beds 5***** B&B max 4 pers From CHF 125.00 / pers / night Set within a prestigious 17th Century master house, this vast guest room, which Château de Mathod Tel.: +41 (0)79 873 88 60 has been entirely renovated and tastefully decorated, welcomes guests into a Route de Suscévaz 4 e-mail: [email protected] warm and relaxing atmosphere. The room has its own entrance and includes use 1438 Mathod www.chateaudemathod.ch of the garden “Jardin du Parterre” and access to the swimming pool. Guest suite - 2 beds 4****sup FST max 2 pers CHF 199.00 / 1 pers / night // CHF 229.00 / 2 pers / night Junod House is situated in the heart of the historical village of Romainmôtier, 50m Maison Junod Tel.: +41 (0)24 453 14 58 from the Abbey and the prior’s house. The authentic and warm interior decoration Rue du Bourg 19 e-mail: [email protected] is inspired by nature and the stone of the surrounding area. Each room has a 1323 Romainmôtier www.maisonjunod.ch/fr private bathroom. Breakfast is not included. -

Upper Rhine Valley: a Migration Crossroads of Middle European Oaks

Upper Rhine Valley: A migration crossroads of middle European oaks Authors: Charalambos Neophytou & Hans-Gerhard Michiels Authors’ affiliation: Forest Research Institute (FVA) Baden-Württemberg Wonnhaldestr. 4 79100 Freiburg Germany Author for correspondence: Charalambos Neophytou Postal address: Forest Research Institute (FVA) Baden-Württemberg Wonnhaldestr. 4 79100 Freiburg Germany Telephone number: +49 761 4018184 Fax number: +49 761 4018333 E-mail address: [email protected] Short running head: Upper Rhine oak phylogeography 1 ABSTRACT 2 The indigenous oak species (Quercus spp.) of the Upper Rhine Valley have migrated to their 3 current distribution range in the area after the transition to the Holocene interglacial. Since 4 post-glacial recolonization, they have been subjected to ecological changes and human 5 impact. By using chloroplast microsatellite markers (cpSSRs), we provide detailed 6 phylogeographic information and we address the contribution of natural and human-related 7 factors to the current pattern of chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) variation. 626 individual trees 8 from 86 oak stands including all three indigenous oak species of the region were sampled. In 9 order to verify the refugial origin, reference samples from refugial areas and DNA samples 10 from previous studies with known cpDNA haplotypes (chlorotypes) were used. Chlorotypes 11 belonging to three different maternal lineages, corresponding to the three main glacial 12 refugia, were found in the area. These were spatially structured and highly introgressed 13 among species, reflecting past hybridization which involved all three indigenous oak species. 14 Site condition heterogeneity was found among groups of populations which differed in 15 terms of cpDNA variation. This suggests that different biogeographic subregions within the 16 Upper Rhine Valley were colonized during separate post-glacial migration waves. -

Insights Into the Thermal History of North-Eastern Switzerland—Apatite

geosciences Article Insights into the Thermal History of North-Eastern Switzerland—Apatite Fission Track Dating of Deep Drill Core Samples from the Swiss Jura Mountains and the Swiss Molasse Basin Diego Villagómez Díaz 1,2,* , Silvia Omodeo-Salé 1 , Alexey Ulyanov 3 and Andrea Moscariello 1 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, 13 rue des Maraîchers, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland; [email protected] (S.O.-S.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex GU28 0LH, UK 3 Institut des sciences de la Terre, University of Lausanne, Géopolis, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This work presents new apatite fission track LA–ICP–MS (Laser Ablation Inductively Cou- pled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) data from Mid–Late Paleozoic rocks, which form the substratum of the Swiss Jura mountains (the Tabular Jura and the Jura fold-and-thrust belt) and the northern margin of the Swiss Molasse Basin. Samples were collected from cores of deep boreholes drilled in North Switzerland in the 1980s, which reached the crystalline basement. Our thermochronological data show that the region experienced a multi-cycle history of heating and cooling that we ascribe to burial and exhumation, respectively. Sedimentation in the Swiss Jura Mountains occurred continuously from Early Triassic to Early Cretaceous, leading to the deposition of maximum 2 km of sediments. Subsequently, less than 1 km of Lower Cretaceous and Upper Jurassic sediments were slowly eroded during the Late Cretaceous, plausibly as a consequence of the northward migration of the forebulge Citation: Villagómez Díaz, D.; Omodeo-Salé, S.; Ulyanov, A.; of the neo-forming North Alpine Foreland Basin. -

Liste Des Communes Du Nouveau Zonage Sismique

Extraction site Internet INSEE Population N° aléa sismique N° département Libellé commune municipale INSEE 2005 (année 2006) 25001 25 ABBANS-DESSOUS 239 Modéré 25002 25 ABBANS-DESSUS 317 Modéré 25003 25 ABBENANS 349 Modéré 25004 25 ABBEVILLERS 1 000 Moyen 25005 25 ACCOLANS 87 Modéré 25006 25 ADAM-LES-PASSAVANT 85 Modéré 25007 25 ADAM-LES-VERCEL 83 Modéré 25008 25 AIBRE 456 Modéré 25009 25 AISSEY 165 Modéré 25011 25 ALLENJOIE 653 Modéré 25012 25 LES ALLIES 107 Modéré 25013 25 ALLONDANS 205 Modéré 25014 25 AMAGNEY 714 Modéré 25015 25 AMANCEY 627 Modéré 25016 25 AMATHAY-VESIGNEUX 134 Modéré 25017 25 AMONDANS 87 Modéré 25018 25 ANTEUIL 511 Modéré 25019 25 APPENANS 410 Modéré 25020 25 ARBOUANS 997 Modéré 25021 25 ARC-ET-SENANS 1 428 Modéré 25022 25 ARCEY 1 332 Modéré 25024 25 ARCON 750 Modéré 25025 25 ARC-SOUS-CICON 603 Modéré 25026 25 ARC-SOUS-MONTENOT 226 Modéré 25027 25 ARGUEL 242 Modéré 25028 25 ATHOSE 143 Modéré 25029 25 AUBONNE 251 Modéré 25030 25 AUDEUX 428 Faible 25031 25 AUDINCOURT 14 637 Modéré 25032 25 AUTECHAUX 350 Modéré 25033 25 AUTECHAUX-ROIDE 565 Modéré 25034 25 AUXON-DESSOUS 1 158 Faible 25035 25 AUXON-DESSUS 1 039 Faible 25036 25 AVANNE-AVENEY 2 307 Modéré 25038 25 AVILLEY 166 Modéré 25039 25 AVOUDREY 754 Modéré 25040 25 BADEVEL 882 Moyen 25041 25 BANNANS 357 Modéré 25042 25 LE BARBOUX 227 Modéré 25043 25 BART 1 944 Modéré 25044 25 BARTHERANS 48 Modéré 25045 25 BATTENANS-LES-MINES 55 Modéré 25046 25 BATTENANS-VARIN 54 Modéré 25047 25 BAUME-LES-DAMES 5 349 Modéré 25048 25 BAVANS 3 620 Modéré 25049 25 BELFAYS 99 Modéré 25050 -

Response of Drainage Systems to Neogene Evolution of the Jura Fold-Thrust Belt and Upper Rhine Graben

1661-8726/09/010057-19 Swiss J. Geosci. 102 (2009) 57–75 DOI 10.1007/s00015-009-1306-4 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2009 Response of drainage systems to Neogene evolution of the Jura fold-thrust belt and Upper Rhine Graben PETER A. ZIEGLER* & MARIELLE FRAEFEL Key words: Neotectonics, Northern Switzerland, Upper Rhine Graben, Jura Mountains ABSTRACT The eastern Jura Mountains consist of the Jura fold-thrust belt and the late Pliocene to early Quaternary (2.9–1.7 Ma) Aare-Rhine and Doubs stage autochthonous Tabular Jura and Vesoul-Montbéliard Plateau. They are and 5) Quaternary (1.7–0 Ma) Alpine-Rhine and Doubs stage. drained by the river Rhine, which flows into the North Sea, and the river Development of the thin-skinned Jura fold-thrust belt controlled the first Doubs, which flows into the Mediterranean. The internal drainage systems three stages of this drainage system evolution, whilst the last two stages were of the Jura fold-thrust belt consist of rivers flowing in synclinal valleys that essentially governed by the subsidence of the Upper Rhine Graben, which are linked by river segments cutting orthogonally through anticlines. The lat- resumed during the late Pliocene. Late Pliocene and Quaternary deep incision ter appear to employ parts of the antecedent Jura Nagelfluh drainage system of the Aare-Rhine/Alpine-Rhine and its tributaries in the Jura Mountains and that had developed in response to Late Burdigalian uplift of the Vosges- Black Forest is mainly attributed to lowering of the erosional base level in the Back Forest Arch, prior to Late Miocene-Pliocene deformation of the Jura continuously subsiding Upper Rhine Graben. -

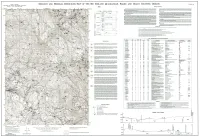

DOGAMI GMS-22, Geology and Mineral Resources Map of the Mt

ST ATE OF OREGON GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES MAP OF THE MT. IRELAND QUADRANGLE, BAKER AND GRANT COUNTIES, OREGON G M S - 22 DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUS TRIES DON ALD A . HULL, STATE G EOLOGIST 1982 MINERAL DEPOSITS 118 4 22'30" 44"52'30" ,. Gold and silver from quart.7. vein and placerdeposit.s have been the .111.llln mineral productsofthe quadrangle, which covel'8moatof senopyrite, and rosc.oelite. At the lbelf. .and Bald Mountain Mines, t h.e gold is about 30 percent free. The rema inder is in J!,Ulfide miner the Cable Cove mining district and parts of the Crack.er Creek and Granite districts. Usinghistorica1 values for gold and silver at the als, which. include arsenopyrile, schwatrite (ml:!rcurial tetrahedri tel, and secondary cinnabar. Pyrargyrite and native .'!i!ver are found time of mining, total value of the output from mines in the quadrangle has. bee.n about $1 .2 million, with the bulk of the production loca.lly. The llU lfi de minerals ge. ner.all y comprise less than 6 percent of the ore. The ratio of gold to silver varies but averages t1bout coming from mines along the Eald Mountain-Ibex vein. 1:10. 'fKMJE R.O>C K CHAR.'f In addition to gold and silver, small amol,lllta of lead, :cine, and copper have been li'/Covered as by-producla from the complex sul· phide ores in the Cable Cove district. Low-grade chromite deposits also occur within the quadrangle. Cable Cove dlstrlet Holocene Oal • Known mines and prospect!, 8N! located on the map by numben!, that correspond to the Ii.at of names and locatioms in Table 1. -

Juillet 2018

Juillet 2018 Aclens – Salle Polyvalente et Foyer Responsable de location : Administration communale Salle polyvalente : La Ferme de Commune Nombre de places : 250 personnes avec 1123 Aclens des tables Tél. 021 869 93 58 Aménagement intérieur : chaises, tables, [email protected] cuisine équipée, cuisinière, vaisselle, www.aclens.ch réfrigérateur, chauffage, sanitaires, vestiaire Salle : Aménagement extérieur : place de jeux, Salle polyvalente et foyer places de parc Rue des Alpes 1123 Aclens Foyer : Nombre de places : 60 personnes Aménagement intérieur : tables, chaises, cuisine équipée industriellement Allaman – Grande salle communale Responsable de location Municipal Nombre de places : 280 personnes Patrick Guex Aménagement intérieur : cuisine 1165 Allaman équipée, cuisinière, vaisselle, réfrigérateur, Tél : 078 670 36 31 chauffage, sanitaires www.allaman.ch Aménagement extérieur : places de parc Salle Grande salle communale Située en face de la gare 1165 Allaman Apples - Refuge de Saint-Pierre Responsable de Location André Rochat Nombre de places: 10 à 15 personnes à Garde Forestier l'intérieur 1143 Apples Aménagement intérieur: tables, chaises Tél: 021 800 36 76 sans eau, sans Natel: 079 658 73 58 électricité, sans WC, sans vaisselle www.apples.ch Salle Refuge de Saint-Pierre Situé dans les bois de la commune d'Apples Au-dessus du manège d'Apples 1143 Apples Apples - Refuge du Bon Responsable de Location Christine Gilléron Nombre de places: 50 personnes à Route de Bière 11 l'intérieur et 30 à l'extérieur 1143 Apples Aménagement intérieur: -

Est Ouest Nord Centre

Etat de Vaud / DIRH Direction générale de Cudrefin la mobilité et des routes Manifestations et appuis Vully-les-Lacs signalisation de chantier Provence Faoug Inspecteurs de Nord Chevroux Voyer de Mutrux DGMR Avenches Missy Grandcour Monsieur Sébastien Berger l'arrondissement Nord Fiez Tévenon la signalisation Mauborget Concise Fontaines/Grand Corcelles-Conc. Place de la Riponne 10 Claude Muller Bonvillars Grandevent Onnens (Vaud) Bullet Corcelles-p/Pay 1014 Lausanne Champagne 024 557 65 65 Novalles Date Dessin Echelle N° Plan Fiez Sainte-Croix Vugelles-La Mot Grandson Payerne 29.08.2016 SF - - Giez Orges 021 316 70 62 et 079 205 44 48 Vuiteboeuf Q:\App\Arcgis\Entretien\Inspecteurs\ER_PLA_Inspecteurs_signalisation Valeyres-ss-Mon Montagny-p.-Yv. [email protected] Cheseaux-Noréaz Yvonand Baulmes Champvent Rovray Villars-Epeney Chamblon Chavannes-le-Ch Treytorrens(Pay Trey Treycovagnes Cuarny Rances Yverdon-les-B. Chêne-Pâquier Molondin Suscévaz L'Abergement Mathod Valbroye Pomy Champtauroz Cronay Sergey Valeyres-sous-R Lignerolle Démoret Légalisation (Nord & Ouest) Ependes (Vaud) Valeyres/Ursins Donneloye Henniez Villarzel Ballaigues Belmont-s/Yverd Montcherand Ursins Les Clées Orbe Essert-Pittet Bioley-Magnoux Forel-s/Lucens Orzens Valbroye Suchy Cremin Agiez DGMR Bretonnières Essertines-s/Yv Oppens Légalisation (Centre & Est) Villars-le-Comt Vallorbe Premier Dompierre (Vd) Chavornay Ogens Lucens Monsieur Vincent Yanef Bofflens Corcelles-s/Ch. Pailly Curtilles Rueyres Prévonloup Montanaire Arnex-sur-Orbe Lovatens Bercher Romainmôtier-E. Bussy-s/Moudon Place de la Riponne 10 Vaulion Juriens Croy Vuarrens DGMR Penthéréaz Bavois Sarzens Pompaples Boulens Croy Fey Chesalles/Moud. 1014 Lausanne La Praz Orny Moudon Monsieur Dominique Brun Brenles Le Lieu Ferreyres Goumoëns Chavannes/Moud. -

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat A Concise Dictionary of Middle English Table of Contents A Concise Dictionary of Middle English...........................................................................................................1 A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat........................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................3 NOTE ON THE PHONOLOGY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH...................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS (LANGUAGES),..................................................................................................11 A CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH....................................................................................12 A.............................................................................................................................................................12 B.............................................................................................................................................................48 C.............................................................................................................................................................82 D...........................................................................................................................................................122 -

Portrait De Territoire Nord Franche

Nord Franche-Comté - Canton du Jura Un territoire contrasté entre une partie française urbaine à forte densité et un côté suisse moins peuplé vec 330 000 habitants, le territoire « Nord Franche-Comté - Canton du Jura » est le plus peuplé des quatre territoires de coopération. Il comprend les agglomérations françaises de Belfort et de Montbéliard. En Suisse, deux pôles d’emploi importants, ceux de Delémont et de Porrentruy, attirent des actifs résidant dans les petites communes françaises situées le long de la frontière. L’industrie est bien implantée dans ce territoire, structurée autour de grands établissements relevant en grande partie de la fabrication de matériel de transport côté Afrançais, davantage diversifiée côté suisse. Démographie : une évolution contrastée Ce territoire se caractérise par de part et d’autre de la frontière des collaborations régulières et multiscalaires qui associent principalement le Canton du Jura, Le territoire « Nord Franche-Comté - Canton (14 100) et une vingtaine de communes de le Département du Territoire de Belfort, du Jura » est un territoire de 330 000 habitants plus de 2000 habitants. la Communauté de l’Agglomération situé dans la partie la moins montagneuse de Le contraste est fort avec la partie suisse, si- Belfortaine (CAB) et la Préfecture du l’Arc jurassien. De fait, il est densément peu- tuée dans le canton du Jura, qui compte 105 Territoire de Belfort. plé, avec 226 habitants au km² alors que la habitants au km² et comprend moins d’une di- De nombreuses réalisations sont à relever, moyenne de l’Arc jurassien se situe à 133 ha- zaine de communes dépassant les 2000 habi- notamment dans le domaine culturel bitants au km².