(Title of the Thesis)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014

AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014 AFRREV STECH An International Journal of Science and Technology Bahir Dar, Ethiopia Vol. 3 (2), S/No 7, May, 2014: 51-65 ISSN 2225-8612 (Print) ISSN 2227-5444 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/stech.v3i2.4 THE USE OF COMPOSITE WATER POVERTY INDEX IN ASSESSING WATER SCARCITY IN THE RURAL AREAS OF OYO STATE, NIGERIA IFABIYI, IFATOKUN PAUL Department of Geography and Environmental Management, Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ilorin; Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria E-mail: 234 8033231626 & OGUNBODE, TIMOTHY OYEBAMIJI Faculty of Law Bowen University, Iwo Osun State, Nigeria Abstract Physical availability of water resources is beneficial to man when it is readily accessible. Oyo State is noted for abundant surface water and appreciable groundwater resources in its pockets of regolith aquifers; as it has about eight months of rainy season and a relatively deep weathered regolith. In spite of this, cases of water associated diseases Copyright© IAARR 2014: www.afrrevjo.net 51 Indexed and Listed in AJOL, ARRONET AFRREV STECH, Vol. 3(2) May, 2014 and deaths have been reported in the rural areas of the state. This study attempts to conduct an investigation into accessibility to potable water in the rural areas of Oyo State, Nigeria via the component approach of water poverty index (WPI). Multistage method of sampling was applied to select 5 rural communities from 25 rural LGAs out of the 33 LGAs in the State. Data were collected through the administration of 1,250 copies of questionnaire across 125 rural communities. Component Index method as developed by Sullivan, et al (2003) was modified and used in this study. -

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (Mfbs) in NIGERIA AS ATJUNE 30, 2019

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS ATJUNE 30, 2019 CURRENT S/NO NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE STATUS 1 AACB MFB NNEWI / AGULU ROAD, ADAZI ANI , ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE 2 AB MFB 9, OBA AKRAN ROAD, IKEJA, LAGOS LAGOS NATIONAL 3 ABC MFB MISSION ROAD, OKADA, ORIN NORTH-EAST LGA, EDO STATE EDO TIER 2 UNIT 4 ABESTONE MFB COMMERCE HOUSE, BESIDE GOVERNMENT HOUSE, IGBEIN HILLS, ABEOKUTA, LAGOS STATE OGUN TIER 1 UNIT 5 ABIA STATE UNIVERSITY MFB UTURU, ISUIKWUATO LGA, ABIA STATE ABIA STATE 6 ABIGI MFB 28, MOBORODE ODOFIN ST., ABIGI IJEBU WATERSIDE, OGUN STATE OGUN TIER 2 UNIT 7 ABOVE ONLY MFB BENSON IDAHOSA UNIVERSITY CAMPUS, UGBOR,BENIN CITY, BENIN, EDO STATE EDO TIER 1 UNIT 8 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY (ATBU) MFBABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, YELWA CAMPUS, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE BAUCHI TIER 1 UNIT 9 ABUCOOP MFB PLOT 251, MILLENIUM BUILDERS PLAZA, HERBERT MACAULAY WAY, CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT, GARKI, ABUJA FCT STATE 10 ABULESORO MFB LTD E7, ADISA STREET, ISAN EKITI EKITI TIER 2 UNIT 11 ACCION MFB ELIZADE PLAZA, 4TH FLOOR, 322A IKORODU ROAD, ANTHONY, IKEJA, LAGOS LAGOS NATIONAL 12 ACE MFB 3 DANIEL ALIYU STREET, KWALI, F.C.T., ABUJA FCT TIER 2 UNIT 13 ACHINA MFB OYE MARKET SQUARE ACHINA AGUATA L.G.A ANAMBRA. ANAMBRA TIER 2 UNIT 14 ACTIVE-POINT MFB 150, ORON ROAD UYO AKWA IBOM AKWA IBOM TIER 1 UNIT 15 ADA MFB AGWADA TOWN, KOKONA LOCAL GOVT AREA, NASARAWA STATE NASARAWA TIER 2 UNIT 16 ADAZI NNUKWU MFB NEAR EKE MARKET, ADAZI NNUKWU, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA TIER 2 UNIT 17 ADAZI-ENU MFB NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA LGA, -

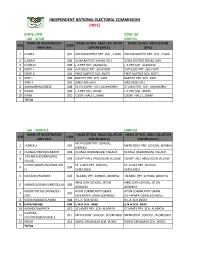

State: Oyo Code: 30 Lga : Afijio Code: 01 Name of Registration Name of Reg

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: OYO CODE: 30 LGA : AFIJIO CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ILORA I 001 OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA OKEDIJI BAPTIST PRY. SCH., ILORA 2 ILORA II 002 ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. ILORA BAPTIST GRAM. SCH. 3 ILORA III 003 L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. L.A PRY SCH. ALAWUSA. 4 FIDITI I 004 CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI CATHOLIC PRY. SCH FIDITI 5 FIDITI II 005 FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI FIRST BAPTIST SCH. FIDITI 6 AWE I 006 BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE BAPTIST PRY. SCH. AWE 7 AWE II 007 AWE HIGH SCH. AWE HIGH SCH. 8 AKINMORIN/JOBELE 008 ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN ST.JOHN PRY. SCH. AKINMORIN 9 IWARE 009 L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. L.A PRY SCH. IWARE. 10 IMINI 010 COURT HALL 1, IMINI COURT HALL 1, IMINI TOTAL LGA : AKINYELE CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) CENTRE (RACC) METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, 1 IKEREKU 001 METHODIST PRY. SCHOOL, IKEREKU IKEREKU 2 OLANLA/OBODA/LABODE 002 OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE OLANLA (OGBANGAN) VILLAGE EOLANLA (OGBANGAN) 3 003 COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE COURT HALL ARULOGUN VILLAGE VILLAG OLODE/AMOSUN/ONIDUND ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, ST. LUKES PRY. SCHOOL, 4 004 U ONIDUNDU ONIDUNDU 5 OJO-EMO/MONIYA 005 ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ISLAMIC PRY. SCHOOL, MONIYA ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN ANGLICAN SCHOOL, OTUN 6 AKINYELE/ISABIYI/IREPODUN 006 AGBAKIN AGBAKIN IWOKOTO/TALONTAN/IDI- AYUN COMMUNITY GRAM. -

A Case Study of Amo Farms, AWE AFIJIO, Oyo State Onosemuode Christopher1, Abodurin Wasiu Adeyemi1

The Use of Geoinformtics in Site Selection for Suitable Landfill for Poultry Waste: A Case Study of Amo Farms, AWE AFIJIO, Oyo State Onosemuode Christopher1, Abodurin Wasiu Adeyemi1 1Department of Environmental Science, College of Sciences, Federal University of Petroleum Resources, Effurun ABSTRACT: This study focused on selection of suitable landfill site for poultry waste in Amo farms Nigeria Limited Awe, Afijio Local Government. The data sets used for the study include; Satellite imagery (Landsat) and topographic maps of the study area. The layers created include those for roads, water bodies, farm sites and the slope map of the study area to determine the degree of slope. The various created layers were subjected to buffering, overlay and query operations using ArcGis 9.3 alongside the established criteria for poultry waste site selection. At the end of the analytical processes, search query was used to generate two most suitable sites of an area that is less than or equal to 20,000m2 (2 hectares). Keywords: Poultry, waste, Site, Geoinformatics, Selection INTRODUCTION is need for both private and public authorities to build up efforts at managing the various wastes generated Disposal sites in some developing countries Nigeria by these various agricultural set-ups. In order to do inclusive are usually not selected in line with this, GIS plays a leading role in selecting suitable established criteria aimed at safeguarding the location for waste disposal sites based on its planning environment and public health. Refuse dumps are and operations that are highly dependent on spatial sited indiscriminately without adequate hydro- data. Generally speaking, GIS plays a key role in geological and geotechnical considerations. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares. -

Oyo State Ubec Fts Shortlist

UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION COMMISSION (UBEC) FEDERAL TEACHERS’ SCHEME (FTS) SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES OYO STATE EXAM S/NO NAME STATE LGA SEX COURSE OF STUDY STATUS NO AMINAT ODEDELE 1 001YY OYO AFIJIO F PHYSICS/MATHEMATICS SHORTLISTED OMOLOLA ABOSEDE 2 002YY AKINRINOLA OYO AFIJIO F BIOLOGY EDUCATION SHORTLISTED DEBORAH ESTHER 3 003YY FEYISETAN OYO AFIJIO F EDUCATION/ENGLISH SHORTLISTED OLUWAFERANMI OLUWATOYIN INTEGRATED 4 004YY OLAGBAMI OYO AFIJIO F SHORTLISTED SCIENCE/BIOLOGY IFEOLUWA SUNDAY 5 005YY ADEKANBI OYO AFIJIO M MATHEMATICS SHORTLISTED OLANREWAJU OLUWATOSIN 6 006YY OYO AFIJIO M EDUCATION/MATHEMATICS SHORTLISTED AKANO JOHN BLESSING 7 007YY ADEBOWALE OYO AFIJIO F BIOLOGY /CHEMISTRY SHORTLISTED OPEYEMI ADEBUNMI OJO 8 008YY OYO AFIJIO F HOME ECONOMICS SHORTLISTED NIKE IFETAYO DAIRO 9 009YY OYO AFIJIO M HUMAN KINETICS SHORTLISTED ELIJAH ADEOLU ADELEYE 10 010YY OYO AFIJIO M SPECIAL EDUCATION/MATHE SHORTLISTED AKINTUNDE REUBEN 11 011YY FUNMILAYO OYO AFIJIO M YORUBA SHORTLISTED ADEGOKE TOHEEB AJAO SPECIAL 12 012YY OYO AFIJIO M SHORTLISTED OPEYEMI EDUCATION/MATHEM ABOSEDE 13 013YY OGUNTUNJI OYO AFIJIO F BIOLOGY SHORTLISTED REBECCA OMOLOLA 14 014YY OGUNKUNLE OYO AFIJIO F BIOLOGY EDUCATION SHORTLISTED ABOSEDE FAITH OLAJIRE 15 015YY OYO AKINYELE F MATHEMATICS/GEOGRAPHY SHORTLISTED OMOWUMI TITILOPE AREMU 16 016YY OYO AKINYELE F FINE ART SHORTLISTED ADEBISI RAFIAT COMPUTER 17 017YY SALAWUDEEN OYO AKINYELE F SHORTLISTED SCIENCE/MATHEMA ADENIKE GAFAR KOLAPO ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND 18 018YY OYO AKINYELE M SHORTLISTED ABIODUN YORUBA TEJUMADE 19 019YY -

(GIS) in Oyo State, Nigeria

Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth Science International 11(1): 1-15, 2017; Article no.JGEESI.34634 ISSN: 2454-7352 Mapping Groundwater Quality Parameters Using Geographic Information System (GIS) in Oyo State, Nigeria T. O. Ogunbode 1* and I. P. Ifabiyi 2 1Faculty of Basic Medical and Health Sciences, Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography and Environmental Management, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/JGEESI/2017/34634 Editor(s): (1) Wen-Cheng Liu, Department of Civil and Disaster Prevention Engineering, National United University, Taiwan and Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute, National United University, Taipei, Taiwan. Reviewers: (1) H. O. Nwankwoala, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. (2) Dorota Porowska, University of Warsaw, Poland. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/20122 Received 2nd June 2017 th Original Research Article Accepted 9 July 2017 Published 19 th July 2017 ABSTRACT The knowledge of spatial pattern of groundwater quality is important to ensure a holistic approach to the management of the resource quality status in space and time. Thus a sample each of underground water was collected from each of the selected 5 rural communities in each of the selected 25 out of the 33 LGAs in Oyo State for the purpose of quality assessments. Eleven (11) + parameters namely water temperature (°C), pH, electr ical conductivity (EC), Sodium (Na ), SO 4, + Potassium (K ), Nitrate (NO 3), Phosphate (PO 3), coli-form count, Oxidation Redox Potential (ORP) and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) were subjected to standard laboratory analysis. -

7.Results of Geophysical Survey

7.Results of Geophysical Survey 1. General 1-1 Purpose of Geophysical Survey The purpose of the geophysical survey is to find the promising communities with high potential ground water development. 1-2 Contents of geophysical survey -1st Stage (BD1) The geophysical survey was conducted in 100 communities of high priority selected among 220 communities -2nd stage(BD2) 56 communities among 100 communities were analyzed as low potential water development in 1st stage. The geophysical re-survey conducted at these 56 communities and in the new 17 additional communities. Total of geophysical survey including re-survey is 117communities (173 sites). ① Electromagnetic Survey ・Method :Loop-Loop (Srigram) ・Line :more than200 m(5 m interval) ・Equipment :GEONICS EM34 ・Analysis :Horizontal Electric Conductivity Profiling ② Resistivity Survey ・Method :Schlumberger method ・Survey depth:a=100m ・Equipment :ABEM SAS300B ・Analysis :1dimention inversion 2. Result of survey 2-1 Potential of Ground Water Basement of survey area is composed with crystal formation (Granite, Gneiss) in Precambrian Period. Upper stratum is weathered. According to the situation of weathered zone, crack and fault in crystal rock (Granite, Gneiss), the formation of aquifer is not constant due to thickness of weathered zone and scale of crack etc. Formation of aquifer are as follow: ・ It is difficult to find aquifer in fissure zone ・ Main aquifer from the test boreholes are located in the boundary between weathered zone and basement. ・ The thickness of weathered zone needs to be more than 20m for high potential of water development ・ Based on the electric conductivity and existing data, the resistivity of weathered zone needs to be less than 130 ohm-m. -

The Election Management System (Ems) Project Report

THE ELECTION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM (EMS) PROJECT REPORT Independent National Electoral Commission, Abuja ©2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................................................ 6 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 8 1.0 Background to the EMS Project ................................................................................................ 11 1.1 Establishment of the EMS Project Committee ......................................................................... 15 1.2 Membership .............................................................................................................................. 16 1.3 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................................. -

Gamma Radioactivity Levels and Their Corresponding External Exposure of Soil Samples from Tantalite Mining Areas in Oke-Ogun, South-Western Nigeria

Radioprotection 2012 DOI: 10.1051/radiopro/2012003 Vol. 47, n° 2, pages 243 à 252 Article Gamma radioactivity levels and their corresponding external exposure of soil samples from tantalite mining areas in Oke-Ogun, South-Western Nigeria A.K. ADEMOLA1, R.I. OBED2 (Manuscript received 9 September 2011, accepted 16 January 2012) Abstract The radioactivity concentrations of 226Ra, 232Th and 40K were measured using gamma-ray spectroscopy with NaI (Tl) detectors in four tantalite mining sites in the Oke-Ogun area, South-Western Nigeria. The measured values of the activities of 40K, 226Ra and 232Th in the soil samples were found to lie in the ranges 123.7 ± 3.8 – 1372.3 ± 8.6, 16.8 ± 1.6 – 71.1 ± 2.53 and 3.0 ± 0.7 – 31.9 ± 1.0 Bq kg–1, respectively. These samples were also found to have radium equivalent activity in the range 74.2–121.0 Bq kg-1. Values of 0.2–0.3 for the external and 0.3–0.4 for the internal hazard indices were estimated for the samples and the annual effective dose varied from 70.3 ± 13.5 to 100.8 ± 42.8 µSv with a mean of 87.5 ± 18.6 µSv y–1. The annual effective dose is higher than the world average. Keywords: Oke-Ogun / radionuclide / tantalite / natural radioactivity / effective dose 1. Introduction Human beings are exposed to background radiation that stems from both natural and man-made sources. Natural background radiation, which is equivalent to 2.4 mSv per person, makes up approximately 80% of the total radiation to which a person is exposed during one year (IAEA, 1996). -

Private Sector Participation in Solid Waste Management Activities in Ibadan

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized nigeria private sector participation in solid waste management activities in ibadan with support from ey & egipe sarl copyright © 2014 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank rights and permissions with external contributions. The findings, interpre- The material in this work is subject to copyright. tations, and conclusions expressed in this work do Because The World Bank encourages dissemina- not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, tion of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as ments they represent. long as full attribution to this work is given. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of Any queries on rights and licenses, including sub- the data included in this work. The boundaries, col- sidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank ors, denominations, and other information shown Publications, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street on any map in this work do not imply any judgment NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522- on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal 2625; e-mail: [email protected]. status of any territory or the endorsement or accep- tance of such boundaries. Photo credits: Farouk Banna, Ivan Bruce | 3 acknowledgments This report was commissioned by the Public, Pri- The team gratefully acknowledges the comments vate Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) at the and support provided by Oyo State Government, World Bank Group, in collaboration with the World under the guidance and leadership of Governor Bank’s Social, Urban, Rural & Resilience Global Abiola Ajimobi, and in particular Professor Ademo- Practice.