The Control of Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vowels and Consonants

VOWELS VOWELS AND CONSONANTS THIRD EDITION Praise for the previous edition: “This is a fascinating, accessible, and reader-friendly book by a master phonetician, about AND how speech sounds are made, and how they can be analyzed. I warmly recommend the book to everyone with an interest, professional or otherwise, in spoken language.” John Laver, Queen Margaret University College Praise for the third edition: CONSONANTS “This book conveys an amazing range of current science, including phonetics, CONSONANTS psycholinguistics, and speech technology, while being engaging and accessible for novices. This edition maintains Ladefoged’s friendly, enthusiastic style while adding important updates.” Natasha Warner, University of Arizona This popular introduction to phonetics describes how languages use a variety of different sounds, many of them quite unlike any that occur in well-known languages. Peter Ladefoged rightly earned his reputation as one of the world’s leading linguists, and students benefitted from his accessible writing and skill in communicating ideas. The third edition of his engaging introduction to phonetics has now been fully updated to reflect the latest trends in the field. It retains Peter Ladefoged’s expert writing and knowledge, and combines them with Sandra Ferrari Disner’s essential updates on topics including speech technology. Vowels and Consonants explores a wide range of topics, including the main forces operating on the sounds of languages; the acoustic, articulatory, and perceptual THIRD EDITION components of speech; and the inner workings of the most modern text-to-speech systems and speech recognition systems in use today. The third edition is supported by an accompanying website featuring new data, and even more reproductions of the sounds of a wide variety of languages, to reinforce learning and bring the descriptions to life, at www.wiley.com/go/ladefoged. -

Natasha R. Abner –

Natasha R. Abner Interests Sign languages, morpho-syntax, syntax-semantics interface, language development & emergence. Employment 2017–present University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. Assistant Professor Linguistics Department Sign Language & Multi-Modal Communication Lab Language Across Modalities 2014–2017 Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ. Assistant Professor Linguistics Department 2012–2014 University of Chicago, Chicago, IL. Postdoctoral Scholar Goldin-Meadow Laboratory Department of Psychology Education 2007–2012 PhD in Linguistics. University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Fall 2010 Visiting student. Département d’études cognitives École normale supérieure Paris, France 2001–2005 BA in Linguistics, Summa Cum Laude. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Ann Arbor, MI Theses Dissertation Title There Once Was a Verb: The Predicative Core of Possessive and Nominalization Structures in American Sign Language Committee Hilda Koopman and Edward Stabler (chairs), Karen Emmorey, and Edward Keenan Master’s Thesis Title Right Where You Belong: Right Peripheral WH-Elements and the WH-Question Paradigm in American Sign Language Linguistics Department – 440 Lorch Hall – Ann Arbor, MI Ó (734)764-0353 • Q [email protected] Last Updated: April 27, 2019 1/11 Committee Edward Stabler and Anoop Mahajan (chairs), and Pamela Munro Honor’s Thesis Title Resultatives Gone Minimal Advisors Acrisio Pires and Samuel Epstein Grants & Awards 2019 Honored Instructor University of Michigan 2018 New Initiative New Infrastructure (NINI) Grant ($12,500) University of Michigan 2016 Summer Grant Proposal Development Award Montclair State University 2011–2012 Dissertation Year Fellowship UCLA 2010–2011 Charles E. and Sue K. Young Award UCLA + Awarded annually to one student from the UCLA Humanities Division for exemplary achievement in scholarship, teaching, and University citizenship. -

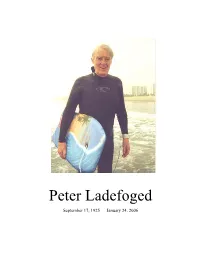

Obituary for Peter Ladefoged (1925-2006)

Obituary for Peter Ladefoged (1925-2006) Peter Ladefoged died suddenly on January 24, 2006, at the age of 80 in London, on his way home from field work in India. He was born on September 17, 1925, in Sutton, Surrey, England. In 1951 he received his MA at the University of Edinburgh and in 1959 his PhD from the same University. At Edinburgh he studied phonetics with David Abercrombie, a pupil of Daniel Jones and so also connected to Henry Sweet. Peter’s dissertation, The Nature of Vowel Quality, focused on the cardinal vowels and their articulatory vs. auditory basis. In 1953, he married Jenny MacDonald. In 1959-62 he carried out field researches in Africa that resulted in A Phonetic Study of West African Languages. In 1962 he moved to America permanently and joined the UCLA English Department where he founded the UCLA Phonetics Laboratory. Not long after he arrived at UCLA, he was asked to work as the phonetics consultant for the movie My Fair Lady (1964). Three main cornerstones characterize Peter’s career: the fieldwork on little-studied sounds, instrumental laboratory phonetics and linguistic phonetic theory. He was particularly concerned about documenting the phonetic properties of endangered languages. His field research work covered a world-wide area, including the Aleutians, Australia, Botswana, Brazil, China, Ghana, India, Korea, Mexico, Nepal, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Scotland, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda and Yemen. Among many distinctive contributions to phonetics was his insistence on the huge diversity of phonetic phenomena in the languages of the world. Ladefoged’s fieldwork originated or refined many data collections and analytic techniques. -

A Tutorial on Acoustic Phonetic Feature Extraction for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Text-To-Speech (TTS) Applications in African Languages

Linguistic Portfolios Volume 9 Article 11 2020 A Tutorial on Acoustic Phonetic Feature Extraction for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Text-to-Speech (TTS) Applications in African Languages Ettien Koffi St. Cloud State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Koffi, Ettien (2020)A " Tutorial on Acoustic Phonetic Feature Extraction for Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Text-to-Speech (TTS) Applications in African Languages," Linguistic Portfolios: Vol. 9 , Article 11. Available at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/stcloud_ling/vol9/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistic Portfolios by an authorized editor of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Koffi: A Tutorial on Acoustic Phonetic Feature Extraction for Automatic Linguistic Portfolios–ISSN 2472-5102 –Volume 9, 2020 | 130 A TUTORIAL ON ACOUSTIC PHONETIC FEATURE EXTRACTION FOR AUTOMATIC SPEECH RECOGNITION (ASR) AND TEXT-TO-SPECH (TTS) APPLICATIONS IN AFRICAN LANGUAGES ETTIEN KOFFI ABSTRACT At present, Siri, Dragon Dictate, Google Voice, and Alexa-like functionalities are not available in any indigenous African language. Yet, a 2015 Pew Research found that between 2002 to 2014, mobile phone usage increased tenfold in Africa, from 8% to 83%.1 The Acoustic Phonetic Approach (APA) discussed in this paper lays the foundation that will make Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) and Text-to-Speech (TTS) applications possible in African languages. The paper is written as a tutorial so that others can use the information therein to help digitalize many of the continent’s indigenous languages. -

Peter Ladefoged

Peter Ladefoged September 17, 1925 — January 24, 2006 p. 2 Jenny and Peter’s Wedding p. 3 A Celebration of the Life of Peter Ladefoged February 4, 2006 Speakers: Tim Stowell, Thegn Ladefoged, Katie Bottom, Shirley Forshee, Robert Stockwell, John Ohala, Ian Maddieson, Louis Goldstein, Sandy Disner, Dani Byrd, Bruce Hayes, Sun-Ah Jun, Sarah Dart, Pat Keating Please join us following the program for chocolate and champagne. p. 4 Peter Ladefoged was born on Sept.17, 1925, in Sutton, Surrey, England. He attended Haileybury from 1938 to 1943, and Caius College Cambridge from 1943 to 1944. His university education was interrupted by his war service in the Royal Sussex Regiment from 1944 to 1947. He resumed his education at the University of Edinburgh, where he received an MA in 1951 and a PhD in 1959. At Edinburgh he studied phonetics with David Abercrombie, who himself had studied with Daniel Jones and was thus connected to Henry Sweet. Peter's dissertation was on The Nature of Vowel Quality, specifically on the cardinal vowels and their articulatory vs. auditory basis. At the same time, he began important research projects with Donald Broadbent, Walter Lawrence, M. Draper, and D. Witteridge, with his first publications appearing in 1956. His 1957 paper with Donald Broadbent, “Information Conveyed by Vowels.” was particularly influential. In 1953, he married Jenny Macdonald; he told her that if she married him they would travel to every continent. In 1959-60 Peter taught in Nigeria, and thus began his lifelong commitment to instrumental phonetic fieldwork. He returned to Africa in 1961-62 to do the work that resulted in A Phonetic Study of West African Languages. -

Rara & Rarissima

Rara & Rarissima — Collecting and interpreting unusual characteristics of human languages Leipzig (Germany), 29 March - 1 April 2006 Invited speakers Larry Hyman (University of California, Berkeley) Frans Plank (Universität Konstanz) Ian Maddieson (University of California, Berkeley) Daniel L. Everett (University of Manchester) Objective Universals of language have been studied extensively for the last four decades, allowing fundamental insight into the principles and general properties of human language. Only incidentally have researchers looked at the other end of the scale. And even when they did, they mostly just noted peculiar facts as "quirks" or "unusual behavior", without making too much of an effort at explaining them beyond calling them "exceptions" to various rules or generalizations. Rarissima and rara, features and properties found only in one or very few languages, tell us as much about the capacities and limits of human language(s) as do universals. Explaining the existence of such rare phenomena on the one hand, and the fact of their rareness or uniqueness on the other, should prove a reasonable and interesting challenge to any theory of how human language works. Themes A suggested (but not exhaustive) list of relevant themes is: examples of rara from various languages examples of rara from all subfields of linguistics distribution and areal patterning the meaning of rara for linguistic theory the importance of rara for historical linguistics the concept of rara and its role in the history of linguistics methods for establishing and finding rara Local Organizers Jan Wohlgemuth, Michael Cysouw, Orin Gensler, David Gil The conference will be held in the lecture hall(s) of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig and adjacent buildings. -

` Peter Ladefoged Soc. Sec. 370 44 3325 Linguistics Department, UCLA

` Peter Ladefoged Soc. Sec. 370 44 3325 Linguistics Department, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543 Telephone 949 916 9063 Fax: (310) 446 1579. E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION University of Edinburgh, Scotland M.A. 1951 University of Edinburgh, Scotland Ph.D. 1959 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 1991: - UCLA Research Linguist Distinguished Professor of Phonetics Emeritus 1965 -1991: Professor of Phonetics, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1977-1980: Chair, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1963-1965: Associate Professor Phonetics, Department of Linguistics, UCLA 1962-1963: Assistant Professor Phonetics, Department of English, UCLA 1961-1962: Field Fellow on the West African Languages Survey 1960-1961: Lecturer in Phonetics, University of Edinburgh 1959-1960: Lecturer in Phonetics, University of Ibadan, Nigeria 1955-1959: Lecturer in Phonetics, University of Edinburgh 1953-1955: Assistant Lecturer in Phonetics, University of Edinburgh MAJOR RESEARCH INTEREST Experimental phonetics as related to linguistic universals HONORS (chronological order) Fellow of the Acoustical Society of America Fellow of the American Speech and Hearing Association Distinguished Teaching Award, UCLA 1972 President, Linguistic Society of America, 1978 President of the Permanent Council for the Organization of International Congresses of Phonetic Sciences, 1983-1991 President, International Phonetic Association, 1987-1991 UCLA Research Lecturer 1989 Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1990 UCLA College of Letters and Science Faculty Research Lecturer 1991 Gold medal, XIIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences 1991 Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy 1992 Honorary D.Litt., University of Edinburgh, 1993 Foreign Member, Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, 1993 Silver medal, Acoustical Society of America 1994 Corresponding Fellow, Royal Society of Edinburgh, 2001 Honorary D.Sc. -

Phonetic Structures of Ndumbea

THE PHONETICS OF NDUMBEA1 MATTHEW GORDON AND IAN MADDIESON UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES 1. INTRODUCTION. This paper discusses the phonetic properties of Ndumbea, one of the indigenous Austronesian languages of the southernmost part of New Caledonia, a French “Overseas Territory” in the South Pacific. The name Ndumbea more properly belongs to a people who have given their name to the present-day capital of the territory, Nouméa, as well as to Dumbéa, a smaller town to the north of Nouméa. Rivierre (1973) uses the phrase [n¢a⁄)a) n¢d¢u~mbea] “language of Nouméa” for the name of the language. The spelling Drubea, using orthographic conventions based on those of Fijian, is preferred in Ozanne-Rivierre and Rivierre (1991). We prefer to represent the prenasalization overtly in the spelling of the language name, but our spelling does not note the post-alveolar place of articulation of the initial stop. In the titles of the books by Païta and Shintani (1983, 1990) and Shintani (1990) the language is referred to as Païta. This is the name of one of the clans speaking the language and it has also become the name of a modern town, Païta. The language is no longer spoken in Dumbéa or Païta but survives in a few rural settlements to the northwest of Nouméa, and in an area reserved for the indigenous inhabitants around Unya (also spelled Ounia) on the east coast. The locations referred to are shown on the map in Figure 1. The total number of remaining speakers of Ndumbea is probably on the order of two or three hundred at most. -

Continuum of Phonation Types

Phonation types: a cross-linguistic overview Matthew Gordon University of California, Santa Barbara Peter Ladefoged University of California, Los Angeles 1. Introduction Cross-linguistic phonetic studies have yielded several insights into the possible states of the glottis. People can control the glottis so that they produce speech sounds with not only regular voicing vibrations at a range of different pitches, but also harsh, soft, creaky, breathy and a variety of other phonation types. These are controllable variations in the actions of the glottis, not just personal idiosyncratic possibilities or involuntary pathological actions. What appears to be an uncontrollable pathological voice quality for one person might be a necessary part of the set of phonological contrasts for someone else. For example, some American English speakers may have a very breathy voice that is considered to be pathological, while Gujarati speakers need a similar voice quality to distinguish the word /baª|/ meaning ‘outside’ from the word /ba|/ meaning ‘twelve’ (Pandit 1957, Ladefoged 1971). Likewise, an American English speaker may have a very creaky voice quality similar to the one employed by speakers of Jalapa Mazatec to distinguish the word /ja0!/ meaning ‘he wears’ from the word /ja!/ meaning ‘tree’ (Kirk et al. 1993). As was noted some time ago, one person's voice disorder might be another person's phoneme (Ladefoged 1983). 2. The cross-linguistic distribution of phonation contrasts Ladefoged (1971) suggested that there might be a continuum of phonation types, defined in terms of the aperture between the arytenoid cartilages, ranging from voiceless (furthest apart), through breathy voiced, to regular, modal voicing, and then on through creaky voice to glottal closure (closest together). -

Representing Linguistic Phonetic Structure Peter Ladefoged 1. What

Representing linguistic phonetic structure Peter Ladefoged 1. What do we want to represent? 1.1 Limiting the scope of phonology. Kinds of information conveyed by speech Sociolinguistic differences are not the same as linguistic differences What counts as a linguistic contrast 1.2 Non-linguistic aspects of speech\ Speaker attitudes, style, peronal identity Spoken language and written language The role of intonation 1.3 Universal phonetics and phonology Equating sounds in different languages IPA categories and phonological feaures Innate features The number of possible contrasting sounds 1.4 Language as a social institution The mental nature of language Language as a self-organizing social institution Filling holes in patterns Phonemes as linguistic constructs 2. What is the purpose of a linguistic phonetic representation 2.1 The nature of phonological features Describing sound patterns vs. specifying the lexicon How sound patterns arise 2.2 The need for auditory/acoustic features Auditory characteristics of vowels Other auditory features 2.3 Defining characteristics of features Features are defined in terms of acoustic or articulatory scales Articulatory features do not have invariant acoustic correlates 2.4 Multi-valued features. Features with an ordered set of values »pit´ »lQdIf´UgId rEprI»sEntIN »lINgwIstIk f´»nEtIk »str√ktS´ 1. What do we want to represent? 1.1 Limiting the scope of phonology. Before we discuss the phonetic representation of a language, we must consider what it is we want to represent, and why we want to represent it. Phonetics is the study of the sounds of speech, so it is these sounds that we want to represent. -

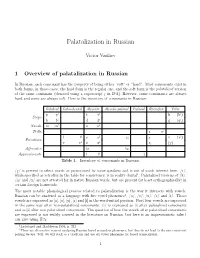

1 Overview of Palatalization in Russian

Palatalization in Russian Victor Vasiliev 1 Overview of palatalization in Russian In Russian, each consonant has the property of being either \soft" or \hard". Most consonants exist in both forms; in those cases, the hard form is the regular one, and the soft form is the palatalized version of the same consonant (denoted using a superscript j in IPA). However, some consonants are always hard and some are always soft. Here is the inventory of consonants in Russian: Bilabial Labiodental Alveolar Alveolo-palatal Palatal Retroflex Velar p pj t tj k (kj) Stops b bj d dj g (gj) Nasals m mj n nj Trills r rj f fj s sj C: ù x (xj) Fricatives v vj z zj ü (G) Affricates ts tC Approximants l lj j Table 1. Inventory of consonants in Russian. /G/ is present in select words as pronounced by some speakers and is not of much interest here. /r/, while specified as retroflex in the table for consistency, is in reality dental1. Palatalized versions of /k/, /g/ and /x/ are not attested for in native Russian words, but are present (at least orthographically) in certain foreign loanwords. The most notable phonological process related to palatalization is the way it interacts with vowels. Russian can be analyzed as a language with five vowel phonemes2,/a/, /o/, /u/, /E/ and /i/. Those vowels are expressed as [a], [o], [u], [E] and [i] in the word-initial position. First four vowels are expressed in the same way after non-palatalized consonants; /i/ is expressed as [i] after palatalized consonants and as [1] after non-palatalized consonants. -

A Course in Phonetics Third Edition

THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (revised to 1989) CONSONANTS A Course In Phonetics Third Edition Peter LadefogedC University of California, ~oshgeles Wheresymbols appear in pain, the one to the right represents a voicedconranant. Shaded areas denote anicularions judged impossible. VOWELS Front Central Back uI.U close-mid e @ Yo0 Open-mid E (R A 3 Open Where symbols appear in pain the one to the right represents a rounded vowel. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers Fort Worth Philadelphia San Diego New York Orlando Austin San Antonio Toronto Montreal London Sydney Tokyo Conttnued on Ins{& back cover Articulatory Phonetics honetics is concerned with describing the speech sounds that occur in P the languages of the world. We want to know what these sounds are, how they fall into patterns, and how they change in different circum- stances. Most importantly, we want to know what aspects of the sounds are necessary for conveying the meaning of what is being said. The first job of a phonetician is, therefore, to try to find out what people are doing when they are talking and when they are listening to speech. We will begin by describing how speech sounds are made. In nearly all speech sounds, the basic source of power is the respiratory system pushing air out of the lungs. Try to talk while breathing in instead of out. You will find that you can do it, but it is much more inefficient than superimposing speech on an outgoing breath. Air from the lungs goes up the windpipe (the trachea, to use the more, technical term) and into the larynx, at which point it must pass between two small muscular folds called the vocal cords.