And Trademark Law Treaty Implementation Act Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campaign Committee Transfers to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee JOHN KERRY for PRESIDENT, INC. $3,000,000 GORE 2

Campaign Committee Transfers to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee JOHN KERRY FOR PRESIDENT, INC. $3,000,000 GORE 2000 INC.GELAC $1,000,000 AL FRIENDS OF BUD CRAMER $125,000 AL COMMITTEE TO ELECT ARTUR DAVIS TO CONGRESS $10,000 AR MARION BERRY FOR CONGRESS $135,000 AR SNYDER FOR CONGRESS CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $25,500 AR MIKE ROSS FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $200,000 AS FALEOMAVAEGA FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $5,000 AZ PASTOR FOR ARIZONA $100,000 AZ A WHOLE LOT OF PEOPLE FOR GRIJALVA CONGRESSNL CMTE $15,000 CA WOOLSEY FOR CONGRESS $70,000 CA MIKE THOMPSON FOR CONGRESS $221,000 CA BOB MATSUI FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $470,000 CA NANCY PELOSI FOR CONGRESS $570,000 CA FRIENDS OF CONGRESSMAN GEORGE MILLER $310,000 CA PETE STARK RE-ELECTION COMMITTEE $100,000 CA BARBARA LEE FOR CONGRESS $40,387 CA ELLEN TAUSCHER FOR CONGRESS $72,000 CA TOM LANTOS FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE $125,000 CA ANNA ESHOO FOR CONGRESS $210,000 CA MIKE HONDA FOR CONGRESS $116,000 CA LOFGREN FOR CONGRESS $145,000 CA FRIENDS OF FARR $80,000 CA DOOLEY FOR THE VALLEY $40,000 CA FRIENDS OF DENNIS CARDOZA $85,000 CA FRIENDS OF LOIS CAPPS $100,000 CA CITIZENS FOR WATERS $35,000 CA CONGRESSMAN WAXMAN CAMPAIGN COMMITTEE $200,000 CA SHERMAN FOR CONGRESS $115,000 CA BERMAN FOR CONGRESS $215,000 CA ADAM SCHIFF FOR CONGRESS $90,000 CA SCHIFF FOR CONGRESS $50,000 CA FRIENDS OF JANE HARMAN $150,000 CA BECERRA FOR CONGRESS $125,000 CA SOLIS FOR CONGRESS $110,000 CA DIANE E WATSON FOR CONGRESS $40,500 CA LUCILLE ROYBAL-ALLARD FOR CONGRESS $225,000 CA NAPOLITANO FOR CONGRESS $70,000 CA PEOPLE FOR JUANITA MCDONALD FOR CONGRESS, THE $62,000 CA COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LINDA SANCHEZ $10,000 CA FRIENDS OF JOE BACA $62,000 CA COMMITTEE TO RE-ELECT LORETTA SANCHEZ $150,000 CA SUSAN DAVIS FOR CONGRESS $100,000 CO SCHROEDER FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE, INC $1,000 CO DIANA DEGETTE FOR CONGRESS $125,000 CO MARK UDALL FOR CONGRESS INC. -

War Powers for the 21St Century: the Congressional Perspective

WAR POWERS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: THE CONGRESSIONAL PERSPECTIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 13, 2008 Serial No. 110–160 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–232PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 12:25 May 12, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\IOHRO\031308\41232.000 Hintrel1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

War Powers for the 21St Century: the Constitutional Perspective

WAR POWERS FOR THE 21ST CENTURY: THE CONSTITUTIONAL PERSPECTIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 10, 2008 Serial No. 110–164 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–756PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 09:32 May 14, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\IOHRO\041008\41756.000 Hintrel1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOWARD L. BERMAN, California, Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey Samoa DAN BURTON, Indiana DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ELTON GALLEGLY, California BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida DONALD A. MANZULLO, Illinois ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BILL DELAHUNT, Massachusetts STEVE CHABOT, Ohio GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado DIANE E. WATSON, California RON PAUL, Texas ADAM SMITH, Washington JEFF FLAKE, Arizona RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri MIKE PENCE, Indiana JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee JOE WILSON, South Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas JOHN BOOZMAN, Arkansas LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California J. GRESHAM BARRETT, South Carolina SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas CONNIE MACK, Florida RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas JEFF FORTENBERRY, Nebraska JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York MICHAEL T. -

Committee on Foreign Affairs

1 Union Calendar No. 559 113TH CONGRESS " ! REPORT 2nd Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 113–728 LEGISLATIVE REVIEW AND OVERSIGHT ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS A REPORT FILED PURSUANT TO RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND SECTION 136 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1946 (2 U.S.C. 190d), AS AMENDED BY SECTION 118 OF THE LEGISLATIVE REORGANIZATION ACT OF 1970 (PUBLIC LAW 91–510), AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 92–136 JANUARY 2, 2015.—Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 49–006 WASHINGTON : 2015 VerDate Sep 11 2014 17:06 Jan 08, 2015 Jkt 049006 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4012 Sfmt 4012 E:\HR\OC\HR728.XXX HR728 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with HEARINGS E:\Seals\Congress.#13 U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP 113TH CONGRESS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman (25–21) CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DANA ROHRABACHER, California Samoa STEVE CHABOT, Ohio BRAD SHERMAN, California JOE WILSON, South Carolina GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey TED POE, Texas GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MATT SALMON, Arizona THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BRIAN HIGGINS, New York JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina KAREN BASS, California ADAM KINZINGER, Illinois WILLIAM KEATING, Massachusetts MO BROOKS, Alabama DAVID CICILLINE, Rhode Island TOM COTTON, Arkansas ALAN GRAYSON, Florida PAUL COOK, California JUAN VARGAS, California GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina BRADLEY S. -

Private Property Rights and Telecommunications Policy: Hearing Before the H

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2000 Private Property Rights and Telecommunications Policy: Hearing Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 106th Cong., Mar. 21, 2000 (Statement of Viet D. Dinh, Prof. of Law, Geo. U. L. Center) Viet D. Dinh Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] CIS-No.: 2000-H521-97 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cong/3 This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cong Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Communications Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons PRIVATE PROPERlY RIGHTS AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS POUCY HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMl\IITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF- REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION - MARCH 21, 2000 Serial No. 70 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 6fK)1l WASHINGTON: 2000 For .ale by the U.S. Government Prmting Office Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Salea Office, Washington, DC 20{02 COMMlTI'EE ON THE JUDICIARY HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL McCOLLUM, Florida HOWARD L. BERMAN, California GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania RICK BOUCHER, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina JERROLD NADLER, New York LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia ELTON GALLEGLY, California - MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLA'fTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California BOB BARR, Georgia MARTIN T. -

Senator Scarnati Denies Links Between Campaign Funds and Legislation Pennsylvania Senate Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati's Office

Senator Scarnati denies links between campaign funds and legislation Pennsylvania Senate Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati’s office denied a report written by Spotlight PA and The Caucus, which stated he and lobbyists were pushing for legislation that would vastly expand gambling in Pennsylvania. In a statement, Mr. Scarnati denied the link between monetary contributions to his campaign and legislative support for additional gambling, calling the report “appalling.” “I have not advocated for members of the Senate to support video gambling legislation,” the statement read. “In fact — in the past I actively worked against legislation that had been proposed for VGTs [video gaming terminals].” The article, which appeared in Friday’s Post-Gazette, which is a journalism partner with Spotlight PA, said that Mr. Scarnati and lobbyists for deep-pocketed video gaming companies, many from out of state, were pushing for the legislation. Spotlight PA and The Caucus defended their story in a tweet Friday. “We @SpotlightPA and @CaucusPA stand firmly behind our reporting on this story. Our reporters remain undeterred in their commitment to fearless journalism that serves Pennsylvania citizens and holds their elected leaders accountable.” The legislation in question would allow bars, restaurants, clubs and other establishments with liquor licenses to have VGTs. As current legislation stands, only truck stops are allowed to have VGTs in them. In his statement Mr. Scarnati noted that Spotlight PA accepts donations from individuals and organizations as one method of funding the publication. Mr. Scarnati closed his statement by saying that he would meet “any further false media statements” with legal action. COVID-19 has changed Trenton lobbying in many ways, from remote conversations to clients’ priorities There was lobbying before March 9 … it consisted of chasing down lawmakers outside Trenton’s State House to either promote or hurt the prospects of legislation lobbyists shepherded for clients. -

Congressional Directory FLORIDA

56 Congressional Directory FLORIDA FLORIDA (Population 1998, 14,916,000) SENATORS BOB GRAHAM, Democrat, of Miami Lakes, FL; born in Coral Gables, FL, on November 9, 1936; graduated, Miami High School, 1955; B.S., University of Florida, Gainesville, 1959; LL.B., Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA, 1962; lawyer; admitted to the Florida bar, 1962; builder and cattleman; elected to the Florida State House of Representatives, 1966; Florida State Senate, 1970±78; Governor of Florida, 1978±86; married the former Adele Khoury in 1959; four children: Gwendolyn Patricia, Glynn Adele, Arva Suzanne, and Kendall Elizabeth; commit- tees: Energy and Natural Resources; Environment and Public Works; Finance; Veterans' Af- fairs; Select Committee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 1986; re- elected for each succeeding term. Office Listings http://www.senate.gov/∼graham [email protected] 524 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510±0903 ............................... (202) 224±3041 Administrative Assistant.ÐKen Klein. TDD: 224±5621 Legislative Director.ÐBryant Hall. Press Secretary.ÐKimberly James. P.O. Box 3050, Tallahassee, FL 32315 ........................................................................ (850) 907±1100 State Director.ÐMary Chiles. Suite 3270, 101 East Kennedy Boulevard, Tampa, FL 33602 .................................... (813) 228±2476 Suite 1715, 44 West Flagler Street, Miami, FL 33130 ............................................... (305) 536±7293 * * * CONNIE MACK, Republican, of Cape Coral, -

Anouncement from the Florida Developmental Disabilities Council

Anouncement from the Florida Developmental Disabilities Council Congressional Action Critical to Avoid Cuts to Developmental Disability Home and Community Based Waiver The Florida House has passed their Appropriations Act. There were no new budget changes for services. The cuts that remain in the House are a cap of $120,000 on Tier One cost plans and the elimination of behavior assistance services in group homes. The Florida Senate also passed their Appropriations Act. Sen. Peaden sponsored an amendment that had passed in the full Appropriations Committee to restore most of the cuts to the Agency for Persons with Disabilities (APD) if the enhanced Medicaid extension dollars - Federal Medical Assistance Percentages (FMAP) - come from the federal government. If the Federal Medicaid Match dollars are authorized there will be no cuts to dollars for consumer cost plans, APD providers and Intermediate Care facilities. The Senate shares the $120,000 cap to Tier One and the behavioral assistance cuts to group homes that the House has in their budget. Because these issues are the same in the House and the Senate, they will not be looked at again in the Budget Conference meetings. The Budget Conference process is a process of negotiating budget item differences from the House and the Senate. Our attention now turns to Congress. The U.S. House of Representatives has been preoccupied with health care reform and does not yet have a date on when they will address the FMAP issue. A jobs bill that includes the enhanced FMAP recently passed the Senate and now must be taken up by the House. -

Pages 153 Through 176 (Delegates)

S T A T E D E L E G A T I O N S State Delegations Number which precedes name of Representative designates Congressional district. Republicans in roman; Democrats in italic; Independents in bold. ALABAMA SENATORS Richard C. Shelby Jeff Sessions REPRESENTATIVES [Republicans, 5; Democrats, 2] 1. Sonny Callahan 5. Robert E. (Bud) Cramer, Jr. 2. Terry Everett 6. Spencer Bachus 3. Bob Riley 7. Earl F. Hilliard 4. Robert B. Aderholt ALASKA SENATORS Ted Stevens Frank H. Murkowski REPRESENTATIVE [Republican, 1] At Large—Don Young 155 STATE DELEGATIONS ARIZONA SENATORS John McCain Jon Kyl REPRESENTATIVES [Republicans, 5; Democrat, 1] 1. Jeff Flake 4. John B. Shadegg 2. Ed Pastor 5. Jim Kolbe 3. Bob Stump 6. J.D. Hayworth ARKANSAS SENATORS Tim Hutchinson Blanche Lambert Lincoln REPRESENTATIVES [Republicans, 3; Democrat, 1] 1. Marion Berry 3. John Boozman 2. Vic Snyder 4. Mike Ross 156 STATE DELEGATIONS CALIFORNIA SENATORS Dianne Feinstein Barbara Boxer REPRESENTATIVES [Republicans, 19; Democrats, 32; Vacant (1)] 1. Mike Thompson 27. Adam Schiff 2. Wally Herger 28. David Dreier 3. Doug Ose 29. Henry A. Waxman 4. John T. Doolittle 30. Xavier Becerra 5. Robert T. Matsui 31. Hilda L. Solis 6. Lynn C. Woolsey 32. Diane E. Watson 7. George Miller 33. Lucille Roybal-Allard 8. Nancy Pelosi 34. Grace F. Napolitano 9. Barbara Lee 35. Maxine Waters 10. Ellen O. Tauscher 36. Jane Harman 11. Richard W. Pombo 37. Juanita Millender-McDonald 12. Tom Lantos 38. Stephen Horn 13. Fortney Pete Stark 39. Edward R. Royce 14. Anna G. Eshoo 40. Jerry Lewis 15. -

Special Election Dates

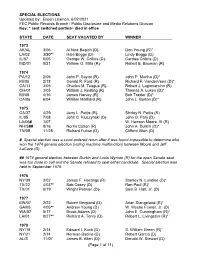

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Procedure and History

Congressional | Saas Research Service Informing the legislative debate since 1914 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Jane A. Hudiburg Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process Christopher M. Davis Analyst on Congress and the Legislative Process Updated February 1, 2018 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R45087 CRS REPORT Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure 1s a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Memberof Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censureis a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure 1s not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. As such, censure resolutions targeting non-Membersusea variety of statements to highlight conduct deemedby the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Resolutions that attempt to censure the President for abuse of power, ethics violations, or other behavior, are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Membersof the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure againstat least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means(a House committee report and an amendmentto a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. A resolution of censure was approved in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

Congressional Directory FLORIDA

68 Congressional Directory FLORIDA *** TWENTY-FIRST DISTRICT THEODORE DEUTCH, Democrat, of Boca Raton, FL; born in Bethlehem, PA, May 7, 1966; education: graduate of Liberty High School; B.A., University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 1988; J.D., University of Michigan Law School, Ann Arbor, MI, 1990; admitted to the Florida bar, 1991; attorney: Florida State Senator, 2006–10; member: Florida Bar Association; Jewish Federation of South Palm Beach County; League of Women Voters; married to the former Jill Weinstock, three children; committees: Ethics; Foreign Affairs; Judiciary; elected to the 111th Congress on April 13, 2010, by special election to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of United States Representative Robert Wexler; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://deutch.house.gov twitter: @repteddeutch 1024 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 ............................. (202) 225–3001 Chief of Staff.—Joshua Rogin. FAX: 225–5974 Deputy Chief of Staff.—Ellen McLaren. Communications Director.—Ashley Mushnick. 8177 West Glades Road, Suite 211 Boca Raton, FL 33434 ....................................... (561) 470–5440 District Director.—Wendi Lipsich. FAX: 470–5446 Counties: BROWARD (part), PALM BEACH (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Boynton Beach, Boca Raton, Delray Beach, Greenacres, Lake Worth, Lantana (only one precinct), West Palm Beach, Coral Springs, Parkland, Coconut Creek, Margate (part), Pompano Beach, and Deerfield Beach. Population (2010), 736,419. ZIP Codes: 33063–66, 33068–69, 33071,