A Catholic Whig in the Age of Reason: Science, Sociability, and the Everyday Life of William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 65 No. 21 January 29, 2019

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Tuesday January 29, 2019 Volume 65 Number 21 www.upenn.edu/almanac Penn Medicine: 25 Years of Charles Bernstein: Bollingen Prize for Poetry Integration, Innovation and Ideals University of Pennsylvania Professor Charles is the Donald T. Re- After 25 years, the combined mission of pa- Bernstein has been named the winner of the gan Professor of Eng- tient care, medical education and research that 2019 Bollingen Prize for American Poetry; it lish and Compara- defines Penn Medicine is a proven principle. As is is among the most prestigious prizes given to tive Literature in the Penn Medicine’s model has evolved over this American writers. School of Arts and Sci- quarter century, it has continually demonstrat- The Bollingen Prize is awarded biennially to ences (Almanac Febru- ed itself to be visionary, collaborative, resilient an American poet for the best book published ary 8, 2005). He is also and pioneering, all while maintaining Frank- during the previous two years, or for lifetime known for his transla- lin’s core, altruistic values of serving the greater achievement in poetry, by the Yale University tions and collabora- good and advancing knowledge. Library through the Beinecke Rare Book and tions with artists and Penn Medicine’s reach and impact would im- Manuscript Library. The Prize was originally libretti. With Al Filreis, press the lifelong teacher and inventor as well. conferred by the Library of Congress with funds Penn’s Kelly Family One of the first integrated academic health sys- established in 1948 by the philanthropist Paul Professor of English, tems in the nation, the University of Pennsylva- Mellon. -

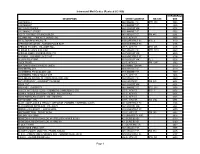

Intramural Mail Codes (Revised 9/21/09) DESCRIPTION STREET

Intramural Mail Codes (Revised 9/21/09) INTRAMURALC DESCRIPTION STREET ADDRESS RM./STE. ODE 3440 MARKET 3440 MARKET ST. STE. 300 3363 3440 MARKET 3440 MARKET ST. 3325 3601 LOCUST WALK 3601 LOCUST WK. 6224 3701 MARKET STREET 3701 MARKET ST. 5502 ACCTS. PAYABLE - FRANKLIN BLDG. 3451 WALNUT ST. RM. 440 6281 ADDAMS HALL - FINE ARTS UGRAD. DIV. 200 S. 36TH ST. 3806 ADDICTION RESEARCH CTR. 3900 CHESTNUT ST. STE. 5 3120 AFFIRMATIVE ACTION - SANSOM PLACE EAST 3600 CHESTNUT ST. 6106 AFRICAN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. STE. 645 6305 AFRICAN STUDIES, CTR. FOR 3401 WALNUT ST. STE. 331A 6228 AFRICAN-AMERICAN RESOURCE CTR. 3537 LOCUST WK. 6225 ALMANAC - SANSOM PLACE EAST 3600 CHESTNUT ST. 6106 ALUMNI RELATIONS 3533 LOCUST WK. FL. 2 6226 AMEX TRAVEL 220 S. 40TH ST RM. 201E 3562 ANATOMY/CHEMISTRY BLDG. (MED.) 3620 HAMILTON WK. 6110 ANNENBERG CTR. 3680 WALNUT ST. 6219 ANNENBERG PSYCHOLOGY LAB 3535 MARKET ST. 3309 ANNENBERG PUBLIC POLICY CTR. 202 S. 36TH ST. 3806 ANNENBERG SCHOOL OF COMMUNICATION - ASC 3620 WALNUT ST. 6220 ANTHROPOLOGY - UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 3260 SOUTH ST. RM. 325 6398 ARCH, THE 3601 LOCUST WK. 6224 ARCHIVES, UNIVERSITY 3401 MARKET ST. STE. 210 3358 ARESTY INST./EXEC. EDUC.- STEINBERG CONFERENCE CTR. 255 S. 38TH ST. STE. 2 6356 ASIAN & MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. 6305 ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES - WILLIAMS HALL 255 S. 36TH ST. 6305 ASTRONOMY - DRL 209 S. 33RD ST. RM. 4N6 6394 AUDIT, COMPLIANCE & PRIVACY, OFFICE OF (FORMERLY INTERNAL AUDIT) 3819 CHESTNUT ST. 3106 BEN FRANKLIN SCHOLARS - THE ARCH 3601 LOCUST WK. -

2020-2021 Academic Calendar

Table of Contents 2020-2021 Academic Calendar .................................................................................................................. 4 Catawba College: A Strength of Tradition .................................................................................................. 7 Non-Discrimination Policy / Title IX Policy ................................................................................................. 9 Admissions Information ........................................................................................................................... 10 Scholarships and Financial Assistance ...................................................................................................... 20 Satisfactory Academic Policy (SAP) ...................................................................................................... 23 Expenses and Fees ................................................................................................................................... 32 The Campus Facilities .............................................................................................................................. 37 Emergency Response Plan ....................................................................................................................... 41 Student Life & Activities........................................................................................................................... 42 Clubs and Organizations ..................................................................................................................... -

0927 Daily Pennsylvanian

Parkway M. Soccer falls Movin’ on up in double-OT Past 40th Street — the Penntrification of West Philly. party See Sports | Back Page See 34th Street Magazine See page 4 The Independent Student Newspaper of the University of Pennsylvania ◆ Founded 1885 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 27, 2007 dailypennsylvaniapennsylvan ian.com PHILADELPHIA | VOL. CXXIII, NO. 84 U. City: Newest dining destination? Penn InTouch changes far on the horizon While student groups call for Penn InTouch improvements, changes likely to take months By REBECCA KAPLAN many believe needs a major Staff Writer overhaul. [email protected] Regina Koch , the IT Techni- Any senior hoping for a sim- cal Director for Student Regis- ple, streamlined class-registra- tration and Financial Services, tion system should stop holding said improving Penn InTouch their breath: Penn InTouch will now is an official project. not be updated this year. “We have to replace some But there is still hope for of the technology because the freshmen, sophomores and ju- systems are 15 years old,” she niors, who will likely see a big said. improvement to the system by Wharton senior Alex Flamm , the time they graduate. the Undergraduate Assembly Last Tuesday, members of representative spearheading the Undergraduate Assembly, the campaign for Penn InTouch Student Financial Services and change, said SFS and ISC are Information Systems and Com- planning a large change sooner puting met to find new ways to than anticipated. improve Penn InTouch, the on- line organization system that See INTOUCH, page 3 Sundance Kid set Staci Hou & Kien Lam/DP File Photos for film screening Top: Morimoto, a Japanese restaurant in Center City owned by Steven Starr. -

Honor and Duty: the Collegiate Education of a Yeoman Farmer's Son

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-1-2021 Honor and Duty: The Collegiate Education of a Yeoman Farmer’s Son in Antebellum Mississippi David Taylor Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, David, "Honor and Duty: The Collegiate Education of a Yeoman Farmer’s Son in Antebellum Mississippi" (2021). Dissertations. 1928. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1928 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HONOR AND DUTY: THE COLLEGIATE EDUCATION OF A YEOMAN FARMER’S SON IN ANTEBELLUM MISSISSIPPI by David Eugene Taylor A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Education and Human Sciences and the School of Education at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Kyna Shelley Holly Foster Lilian Hill Thomas O'Brien August 2021 COPYRIGHT BY David Eugene Taylor 2021 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT This endeavor reviews the mindsets and ideologies emerging from the South in the era known as "King Cotton," a time which predated the American Civil War and in which cotton was the primary export of the South. It is historically relevant to Higher Education in that it views this mindset through the eyes of young, white, single males and in particular, one male, a student of Mississippi College in Clinton, Mississippi. -

A History of the Philomathean Society

i i "f . A HISTORY OF THE Philomathean Society (FOUNDED 1813) WITH A SHORT BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF ALL HER MEMBERS FROM 181 3 TO 1892. Philadelphia. AviL Printing Company. 1892. c.-t'l^..'' Infpoburfopg- It might be well to say, in the beginning of this little book, that the committee in charge of its publication has labored under more than ordi- nary difficulties. The work was originally planned out by the Class of '89, and was intended to be entirely the task of that body. It failed of completion, however, and for several years the whole work has lain dormant, while committee after committee has been appointed, only to be discharged without the publication of the much-heard-of Record. At one time some promise of real work was hoped for when the committee for 1891 was appointed. They labored for some days on the manuscript, until finally the work had to be thrown over on account of the pressure of college work. The present committee, realizing, at last, the burden that this unfinished work was upon Philo, and the obligation the Society was under to complete the publication, have made strenuous efl!brts towards this end, and are glad now to be able to report the completion of the Phi- lomathean Record. The work has been enormous, and would have been impossible without the distinguished aid of several of Philo's loyal gradu- ate members. We are especially indebted to Dr. Frazer, whose kindly assistance and co-operation, in every manner possible, have done much in putting us in a position to complete our difficult task. -

Colonial Echo, 1902

«ps Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from LYRASIS members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/colonialecho190204coll The Colonial Echo 1902 PUBLISHED BY THE STUDENTS OF WILLIAM and MART COLLEGE WILLIAMSBURG —= V I R G I N I A I M^fe— ,A*~" ii A i in i i s: Athletic Association Officers - flC itball Team "i Baseball Team Tennis Club '7° Gymnasium Team Knigl I ludoun 77 s Eastern Shore Club T 7' • 181 Owl Club i Illustration) Disciples oi ( Anarchist Club) 183 s ' Misers' Club • • i Business Mm's Association 185 ' Sleep) Heads . ' 1 ,N robacco Chewers Club 7 Majores Natu |SS lSf Foragers' Organization ' Grub Devourers' Club 19° Kids "" Anti-Calico Club ">-' Vssociated Press Staff 193 Blowers, Bluffs, and Brags >94 The William and Mary Westmoreland Club 195 Aptlj Quoted "'' The Ei ii" Election 198 Advertisements lie ,/\ij }-" II- ^i .* * i I I -A* i §'w4 W- COLORS. Orange and White. Yells. William and Mary, Vir—gin— i —a, Croatan, Powhatan, Ra ! Ra ! Ra ! Zipti Ripti Rev, Zipti, Ripti Rei ! vSpotswood, Botetourt, who are we? Razzle Dazzle, Razzle Dazzle, Sis Room Ba i William and Mary, Vir— gin — — a ! We have made a book which we tondlv dedicate to our sweethearts, for it is theirs. In them we found our inspiration ; to them we turn tor praise. Ever loyal, ever true, they will say it is good. And then the critics may come, and, in their barbarous fashion say uncharitable have things j but we shall be Gentlemen Unafraid; for we shall the delightful satisfaction of knowing that Bright Eyes, wherever they may be, will look with approval upon our work ; that Red Lips will utter kind words for it ; and that Dainty Hands will carefully attend to it that Posterity shall not lose the fruits of our labor. -

No. 21 February 23, 1982

Tuesday; February, 23. 1982 Published by the University of Pennsylvania Volume 28, Number 21 Rallying on Cuts and Consultation it was a week of protests. College and uni- President Sheldon Hackney, returning from versity presidents led off theirs against the Rea- Center City where he had been accepting gan budget last Monday (more on pages 4-5). Mayor Green's citation for leadership in the Students supporting the Voter Rights march in Brailovsky protest (excerpt below), spoke Alabama staged one at noon Thursday. And briefly on the steps of College Hall and an- then came the big one that turned into a sit-in: a swered questions at length. Crowd chants demonstration that pinpointed proposed cuts ranged from "Bullshit!" and "Hell, no, teams in athletics against broader issues of consulta- won't go!" to a more courtly "Let him talk!" tion and of follow-through on existing com- Provost Thomas Ehrlich accompanied the mitments. President but answered only one question: The ten-hour sit-in that ended at midnight Had Academic Planning and Budget been con- Thursday grew out of a rally that started at 1:30 sulted on the 15 percent tuition increase prop- p.m. with the singing of "The Red and the osal? (Answer: "Yes."). Blue." From the steps of College Hall, student Of the 400 or so students who stood in a light leaders of U A, GA PSA, UMC. IFC. arid sev- snowfall for the rally, about half initially sat in, eral team sports (some slated for cuts, some occupying the T-shaped first-floor corridor of not) spoke to a sixteen-point list of demands. -

Download a PDF of This Article

42 NOV | DEC 2013 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE Philo Ph oreverBY CAREN LISSNER As it enters its third century, America’s oldest continuously existing college literary society still has a role to fi ll on campus, in keeping with its unoffi cial motto: “Raise hell with your brain.” Photography by Greg Benson THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE NOV | DEC 2013 43 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE NOV | DEC 2013 45 three Society members published the fi rst the meetings. Other members were un- was in relative decline. That circumstance English language translation in 1858. enthusiastic, according to a history of was not reversed until the 1950s or ’60s. The society also spun off numerous Philo written for its sesquicentennial, but There was the conscious decision by the groups that took on lives of their own. Ludwig won out. That’s still how cabinet president and provost of the University Philos started a forerunner of The Daily members dress today. Ludwig also made to move liberal arts to the center of the Pennsylvanian, founded Mask and Wig the case that Philo should have a regular academic enterprise. Two presidents did and Penn Players, and later helped estab- home, and he ultimately got his way there, this: Gaylord Harnwell [Hon’53, who served lish the comparative-literature and too, when the society fi nally returned to from 1953 to 1970] and Martin Meyerson American-civilization programs at Penn. College Hall in 1967. [Hon’70, in offi ce from 1970 to 1981]. The A Philo history published to mark the Ludwig also actively encouraged the University later combined all of its liber- society’s 100th anniversary in 1913 (avail- involvement of alumni as “senior mem- al-arts programs into the School of Arts able for free download from Google Play, bers,” and set a powerful example with his and Sciences, which dates only from 1975. -

THE ANNALS of IOWA 70 (Winter 2011)

The Annals of Volume 70, Number 1 Iowa Winter 2011 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue MICHAEL S. HEVEL, a doctoral candidate in the higher education program at the University of Iowa, describes the role of literary societies at Cornell College, the State University of Iowa, and the Iowa State Normal School in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He argues that those societies provided opportunities for students to display publicly, in a variety of changing formats over the years, their higher learning. Through their programs, society members demonstrated their educational gains, improved their speaking abilities, and practiced the cultural arts. In addition, society members were instrumental in creating features of campus life that endure to the present. BREANNE ROBERTSON analyzes Lowell Houser’s entry in the compe- tition to create a mural for the Ames Post Office in 1935. She argues that his choice of Mayan subject matter, drawing on a contemporary fascination with Mexican culture in both subject and style, distinguished his work among a strong pool of applicants in the competition, and the execution of his mural sketch, which adhered to traditional notions of history painting, demonstrated a technical and thematic expertise that fulfilled the lofty aims of the selection committee and ultimately won for him the competition. Front Cover Members of the Orio Literary Society at Iowa State Normal School staged a dramatic production of Louis’ Last Moments with His Family in 1897. For more on literary societies at Cornell College, the State University of Iowa, and the Iowa State Normal School, see Michael Hevel’s article in this issue. -

The Role of Literary Societies in Early Iowa Higher Education

Public Displays of Student Learning: The Role of Literary Societies in Early Iowa Higher Education MICHAEL S. HEVEL AT SIX O’CLOCK in the evening on June 13, 1911, student and alumni members of the Zetagathian Literary Society at the State University of Iowa (SUI) gathered in the banquet hall of the Burkley Imperial Hotel in Iowa City to celebrate the organi- zation’s fiftieth anniversary. The 127 “Zets” in attendance, rep- resenting over 10 percent of all the men that the society had ini- tiated since its inception, sat next to former classmates at tables arranged into the letters Z and I. Having paid one dollar for their dinner, many members wore a pennant-shaped red leather badge inscribed in gold lettering with “Zet Semi-Centennial, 1861–1911” that they had received the previous morning at reg- istration. There, in the Drawing Room of the Hall of Liberal Arts (today’s Schaeffer Hall), alumni met the current student mem- bers of the literary society and perused the old society records on display. Later that afternoon the reunion attendees gathered for a photograph in front of the society’s first meeting place, the A State Historical Society of Iowa research grant funded this study. The ar- chivists at Cornell College, the University of Northern Iowa, and the University of Iowa — especially Kathy Hodson, Gerald Peterson, and Jennifer Rouse — proved patient and helpful with my first research project. Professors Linda K. Kerber and Christine A. Ogren at the University of Iowa provided insightful comments on earlier drafts. Suggestions from Annals of Iowa editor Marvin Bergman and the anonymous reviewers greatly improved the final draft. -

Group Name Table Number 180 Degrees Consulting 1 Admissions

GROUP A (Predominantly Academic & Pre-Professional) Group Name Table Number 180 Degrees Consulting 1 Admissions Dean's Advisory Board 2 AI & Society 3 Alpha Iota Gamma 4 Alpha Kappa Psi 5 Alpha Omega Epsilon 6 American Institute of Chemical Engineers 7 Asian Law and Politics Society 8 BBB Society 9 Biomedical Engineering Society 10 Black Pre-Law Association 11 Clio Society 12 College Dean's Advisory Board 13 Collegium Institute Student Association at Penn 14 CURF Undergraduate Advisory Board 15 Delta Sigma Pi 16 Diversity and Inclusion Strategic Consulting (formerly Gender Balance) 17 Diversity in Business Club 18 Engineers in Medicine (eMed) 19 Engineers Without Borders 20 Epsilon Eta 21 Executive MBA Relations Council 22 History Student Society 23 Innovation Acceleration Group 24 International Relations Undergraduate Student Association 25 Israel Leadership Lab 26 Keeping Kids First 27 Meor Penn 28 Minorities in Sports 29 Minority Association of Pre-Health Students (MAPS) 30 MindAlign 31 Penn Philosophy Society 32 National Society of Black Engineers 33 Onyx Senior Honor Society 34 oSTEM 35 Penn ADAPT (Assistive Devices and Prosthetic Technologies) 36 Penn Aerospace Club 37 Penn Association for Women in Mathematics 38 Penn Business Roundtable 39 Penn China-Israel Connection 40 Penn Computer Science Society 41 Penn Fashion Collective 42 Penn Geology Society 43 Penn Global Impact Collaboration 44 Penn Health-Tech Student Board 45 Penn IEEE 46 Penn in Washington 47 Penn International Impact Consulting 48 Penn Ivy Council 49 Penn Microfinance