Trailer and Its Place in a Wider Cinematic Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Other Books by Jonathan Rosenbaum Rivette: Texts and Interviews (editor, 1977) Orson Welles: A Critical View, by André Bazin (editor and translator, 1978) Moving Places: A Life in the Movies (1980) Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983) Midnight Movies (with J. Hoberman, 1983) Greed (1991) This Is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich (editor, 1992) Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995) Movies as Politics (1997) Another Kind of Independence: Joe Dante and the Roger Corman Class of 1970 (coedited with Bill Krohn, 1999) Dead Man (2000) Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Films We Can See (2000) Abbas Kiarostami (with Mehrmax Saeed-Vafa, 2003) Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia (coedited with Adrian Martin, 2003) Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons (2004) Discovering Orson Welles (2007) The Unquiet American: Trangressive Comedies from the U.S. (2009) Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia Film Culture in Transition Jonathan Rosenbaum the university of chicago press | chicago and london Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote for many periodicals (including the Village Voice, Sight and Sound, Film Quarterly, and Film Comment) before becoming principal fi lm critic for the Chicago Reader in 1987. Since his retirement from that position in March 2008, he has maintained his own Web site and continued to write for both print and online publications. His many books include four major collections of essays: Placing Movies (California 1995), Movies as Politics (California 1997), Movie Wars (a cappella 2000), and Essential Cinema (Johns Hopkins 2004). The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. -

Thinking About

THINKING ABOUT Watching, Questioning, Enjoging FOURTH EDITION PETER LEHMAN and WILLIAM LUHR Wiley Biackweii CONTENTS List of Figures ix How to Use This Book xvi Acknowledgments xix About the Companion Blog xxi 1 Introduction 1 Fatal Attraction and Scarface 2 Narrative Structure 27 Jurassic Park and Rashomon 3 Formal Analysis 61 Rules of the Game and The Sixth Sense 4 Authorship 87 The Searchers and Jungle Fever 5 Genres 111 Sin City and Gunfight at the OK Corral 6 Series, Sequels, and Remakes 141 Goldfinger and King Kong (1933 and 2005) 7 Actors and Stars 171 Morocco and Dirty Harry 8 Audiences and Reception 197 A Woman ofParis and The Crying Game 9 Film and the Other Arts 222 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1933) and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) 10 Film and its Relation to Radio and Television 257 Richard Diamond, Private Detective; Peter Gunn; Victor/Victoria; 24\ and Homeland 11 Realism and Theories of Film 296 Tlje Battleship Potemkin and Umberto D 12 Gender and Sexuality 317 The Silence of the Lambs and American Gigolo 13 Race 341 Out of the Past, LA Confidential, and Boyz N the Hood 14 Class 371 Pretty Woman and The People Under the Stairs 15 Citizen Kane: An Analysis 396 Citizen Kane 16 Current Trends: Globalization and China, 3D, IMAX, Internet TV 419 Glossary 441 Index 446 LIST Of FIGURES Chapter 1 1.1 Zero Dark Thirty, © 2012 Zero Dark Thirty LLC 1 1.2 American Sniper, © 2014 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc, Village Roadshow Films North America Inc. and Ratpac-Dune Entertainment LLC 1 1.3 Spotlight, © 2015 SPOTLIGHT FILM, LLC 2 1.4 Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, © 2013 Paramount Pictures Corporation 2 1.5 Dragon: The Brace Lee Story, © 1992, Universal 3 1.6 Breakfast at Tiffany's, © 1961, Paramount 3 1.7 Psycho, © 1960, Universal 3 1.8 The Hills Have Eyes (2006), © 2006 BRC Rights Management, LTD 4 1.9 The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003), © 2003 Chainsaw Productions, LLC 4 1.10 Son of the Pink Panther (1993), © United Artists Productions, Inc. -

'The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World': Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston

1 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 2 (2008): 145- 60, (c) Sage Publications Available online at: http://con.sagepub.com/content/14/2/145.full.pdf+html DOI: 10.1177/1354856507087946 ‘The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World’: Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston Abstract At a time of uncertainty over film and television texts being transferred online and onto portable media players, this article examines one of the few visual texts that exists comfortably on multiple screen technologies: the trailer. Adopted as an early cross-media text, the trailer now sits across cinema, television, home video, the Internet, games consoles, mobile phones and iPods. Exploring the aesthetic and structural changes the trailer has undergone in its journey from the cinema to the iPod screen, the article focuses on the new mobility of these trailers, the shrinking screen size, and how audience participation with these texts has influenced both trailer production and distribution techniques. Exploring these texts, and their technological display, reveals how modern distribution techniques have created a shifting and interactive relationship between film studio and audience. Key words: trailer, technology, Internet, iPod, videophone, aesthetics, film promotion 2 In the current atmosphere of uncertainty over how film and television programmes are made available both online and to mobile media players, this article will focus on a visual text that regularly moves between the multiple screens of cinema, television, computer and mobile phone: the film trailer. A unique text that has often been overlooked in studies of film and media, trailer analysis reveals new approaches to traditional concerns such as stardom, genre and narrative, and engages in more recent debates on interactivity and textual mobility. -

Manuel De Pedrolo's "Mecanoscrit"

Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía Volume 4 Issue 2 Manuel de Pedrolo's "Typescript Article 3 of the Second Origin" Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor Pere Gallardo Torrano Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Other Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo Torrano, Pere (2017) "Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor," Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2167-6577.4.2.3 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique/vol4/iss2/3 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Gallardo Torrano: Catalan Apocalypse: Pedrolo versus the Pastor Brothers The present Catalan cultural and linguistic revival is not a new phenomenon. Catalan language and culture is as old as the better-known Spanish/Castilian is, with which it has shared a part of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The 19th century brought about a nationalist revival in many European states, and many stateless nations came into the limelight. -

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention

Learning Trailer Moments in Full-Length Movies with Co-Contrastive Attention Lezi Wang1?, Dong Liu2, Rohit Puri3??, and Dimitris N. Metaxas1 1Rutgers University, 2Netflix, 3Twitch flw462,[email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. A movie's key moments stand out of the screenplay to grab an audience's attention and make movie browsing efficient. But a lack of annotations makes the existing approaches not applicable to movie key moment detection. To get rid of human annotations, we leverage the officially-released trailers as the weak supervision to learn a model that can detect the key moments from full-length movies. We introduce a novel ranking network that utilizes the Co-Attention between movies and trailers as guidance to generate the training pairs, where the moments highly corrected with trailers are expected to be scored higher than the uncorrelated moments. Additionally, we propose a Contrastive Attention module to enhance the feature representations such that the compara- tive contrast between features of the key and non-key moments are max- imized. We construct the first movie-trailer dataset, and the proposed Co-Attention assisted ranking network shows superior performance even over the supervised1 approach. The effectiveness of our Contrastive At- tention module is also demonstrated by the performance improvement over the state-of-the-art on the public benchmarks. Keywords: Trailer Moment Detection, Video Highlight Detection, Co- Contrastive Attention, Weak Supervision, Video Feature Augmentation. 1 Introduction \Just give me five great moments and I can sell that movie." { Irving Thalberg (Hollywood's first great movie producer). Movie is made of moments [34], while not all of the moments are equally important. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

SHIRLEY MACLAINE to RECEIVE 40Th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD

SHIRLEY MACLAINE TO RECEIVE 40th AFI LIFE ACHIEVEMENT AWARD America’s Highest Honor for a Career in Film to be Presented June 7, 2012 LOS ANGELES, CA, October 9, 2011 – Sir Howard Stringer, Chair of the American Film Institute’s Board of Trustees, announced today the Board’s decision to honor Shirley MacLaine with the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award, the highest honor for a career in film. The award will be presented to MacLaine at a gala tribute on Thursday, June 7, 2012 in Los Angeles, CA. TV Land will broadcast the 40th AFI Life Achievement Award tribute on TV Land later in June 2012. The event will celebrate MacLaine’s extraordinary life and all her endeavors – movies, television, Broadway, author and beyond. "Shirley MacLaine is a powerhouse of personality that has illuminated screens large and small across six decades," said Stringer. "From ingénue to screen legend, Shirley has entertained a global audience through song, dance, laughter and tears, and her career as writer, director and producer is even further evidence of her passion for the art form and her seemingly boundless talents. There is only one Shirley MacLaine, and it is AFI’s honor to present her with its 40th Life Achievement Award." Last year’s AFI Tribute brought together icons of the film community to honor Morgan Freeman. Sidney Poitier opened the tribute, and Clint Eastwood presented the award at evening’s end. Also participating were Casey Affleck, Dan Aykroyd, Matthew Broderick, Don Cheadle, Bill Cosby, David Fincher, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Samuel L. Jackson, Ashley Judd, Matthew McConaughey, Helen Mirren, Rita Moreno, Tim Robbins, Chris Rock, Hilary Swank, Forest Whitaker, Betty White, Renée Zellweger and surprise musical guest Garth Brooks. -

State Oks $240M in Hurricane Aid

PC KICKOFF MEETING ATTRACTS HUNDREDS LOCAL | B1 PANAMA CITY LOCAL & STATE | B1 KITTEN ON MEND AFTER 60-FOOT FALL Tuesday, May 7, 2019 www.newsherald.com @The_News_Herald facebook.com/panamacitynewsherald 75¢ State OKs $240M in hurricane aid Derrick Thompson, left, listens to opening arguments during his murder trial on May 1 at the Bay County Courthouse. Thompson was subsequently convicted of fi rst-degree murder in the killing of Allen Johnson in 2014. [PATTI BLAKE/THE NEWS HERALD] Thompson’s sentence in jury’s hands Triple killer could get niece, cried when reading death penalty for a statement about how her 2014 slaying of friend uncle was kind and generous, Allen Johnson including helping with her horse-riding hobby when By Collin Breaux she was young. [email protected] “It’s about what he still @PCNHCollinB means to us and has done for all of us. Uncle Allen was PANAMA CITY — A jury present throughout all of my will decide whether Der- childhood,” Limmer said. rick Thompson will get life “He made games for each kid without parole or the death because he knew we were all penalty for the 2014 murder different but his to love. ... of Allen Johnson. I won’t be able to call him Thompson was found anymore and tell him how guilty Friday of first-degree thankful I am.” murder and robbery with Carolyn Thompson, a firearm for the killing of Thompson’s mother, was Johnson, a friend, to get called to the stand to talk The words “Keep your head up Panama City” are spray-painted on a cabinet near the former Grocery money to finance an addic- about her son. -

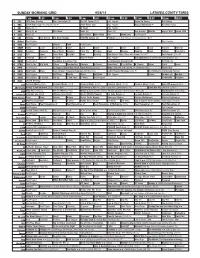

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

In the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas Houston Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION TINA M. RANDOLPH, § § Plaintiff, § § v. § CIVIL ACTION NO. H-08-1836 § DIMENSION FILMS et al.,§ § Defendants. § MEMORANDUM AND ORDER In this action brought under the Copyright Act of 1976, as amended, 17 U.S.C. § 101 et seq., plaintiff Tina M. Randolph, the author of a book published by her “dba,” Rhapsody Publishing, alleges that the defendants infringed on her copyright. The book is Mystic Deja: Maze of Existence, the first of an anticipated twelve-volume science-fiction series. Randolph published it in December 2002. In this suit, she alleges that the defendants’ motion picture, The Adventures of Shark Boy and Lava Girl in 3-D, infringed on her copyrighted book. Randolph also asserts claims for unfair competition under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a), and for violations of the Texas Deceptive Trade Practices Act (DTPA), TEX. BUS. & COM. CODE §§ 17.45(4), 17.50. The defendants, Dimension Films, Miramax Film Corp., SONY Pictures Entertainment, Inc., Buena Vista Home Entertainment, Inc., Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc., The Walt Disney Co., Troublemaker Studios, Robert Rodriguez, Racer Max Rodriguez, and Elizabeth Avellan, have moved to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Randolph attached to her complaint cover artwork from the book and from the allegedly infringing movie, as well as a press release for the series and part of the book. The defendants attached to their motion to dismiss a copy of Randolph’s book and of their movie, which this court has read and watched. -

Cigarette Smoking and Perception of a Movie Character in a Film Trailer

ARTICLE Cigarette Smoking and Perception of a Movie Character in a Film Trailer Reiner Hanewinkel, PhD Objective: To study the effects of smoking in a film named “attractiveness.” The Cronbach ␣ for the attrac- trailer. tiveness rating was 0.85. Design: Experimental study. Results: Multilevel mixed-effects linear regression was used to test the effect of smoking in a film trailer. Smoking in the Setting: Ten secondary schools in Northern Germany. film trailer did not reach significance in the linear regres- sion model (z=0.73; P=.47). Smoking status of the recipi- Participants: A sample of 1051 adolescents with a mean ent (z=3.81; PϽ.001) and the interaction between smok- (SD) age of 14.2 (1.8) years. ing in the film trailer and smoking status of the recipient (z=2.21; P=.03) both reached statistical significance. Ever Main Exposures: Participants were randomized to smokers and never smokers did not differ in their percep- view a 42-second film trailer in which the attractive tion of the female character in the nonsmoking film trailer. female character either smoked for about 3 seconds or In the smoking film trailer, ever smokers judged the char- did not smoke. acter significantly more attractive than never smokers. Main Outcome Measures: Perception of the charac- Conclusion: Even incidental smoking in a very short film ter was measured via an 8-item semantic differential scale. trailer might strengthen the attractiveness of smokers in Each item consisted of a polar-opposite pair (eg, “sexy/ youth who have already tried their first cigarettes. unsexy”) divided on a 7-point scale. -

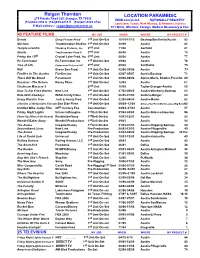

Raigen Thornton LOCATION PARAMEDIC

Raigen Thornton LOCATION PARAMEDIC 275 Private Road 925, Granger, TX 76530 IMDB.com Listed NATIONALLY REGISTRY (512)924-7800 C (512)859-2810 H (512)287-4345 eFax Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, & Arizona Licenses E-Mail address: [email protected] 911 MICU, Offshore, Foreign, Medical Missionary & Film 45 FEATURE FILMS MY JOB WHEN WHERE MY PROJECT # Bernie Deep Freeze Prod 1st Unit On-Set 10/10-11/10 Bastrop/Smithville/Austin 85 Machete Troublemaker Studios 1st Unit On-Set 08/09 Austin 82 Temple Grandin Thinking Pictures, Inc 2nd Unit 11/08 Garfield 81 Shorts Troublemaker Prod 5 2nd Unit 06/08 Austin 78 Friday the 13th Crystal Lake Prod, Inc 2nd Unit 06/08 Austin 77 Ex-Terminator Ex-Terminator Inc 1st Unit On-Set 05/08 Austin 76 Tree of Life Cottonwood Pictures LLC 2nd Unit 05/08 Smithville 75 Will Green Sea Prod. 1st Unit On-Set 02/08-03/08 Austin 73 Fireflies In The Garden Fireflies Inc 1st Unit On-Set 03/07-05/07 Austin/Bastrop 71 There Will Be Blood Paramount 1st Unit On-Set 03/06-08/06 Alpine,Marfa, Shafter,Presidio 69 Revolver –The Return Rosey Films 1st Unit On-Set 12/05 Austin 67 Chainsaw Masacre-3 2nd Unit 10/05 Taylor-Granger-Austin 66 How To Eat Fried Worms New Line 1st Unit On-Set 07/05-09/05 Austin-Wimberly-Bastrop 65 Ride With Cowboys IMAX-Trinity Films 1st Unit On-Set 06/05-07/05 Guthrie-Borger 63 Every Word Is True Jack & Henry Prod. 1st Unit On-Set 02/05-04/05 Austin-Marlin 62 3 Burials of Melquiades Estrada-Sea Side Films 1st Unit On-Set 09/04–12/04 Odessa-VanHorn-Marfa-Lajitas-Big Bend60 Untitled Mike Judge Film 20th