The Anti-Kallar Movement of 1896 / 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name

List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 1 Angambakkam 2 Ariaperumbakkam 3 Arpakkam 4 Asoor 5 Avalur 6 Ayyengarkulam 7 Damal 8 Elayanarvelur 9 Kalakattoor 10 Kalur 11 Kambarajapuram 12 Karuppadithattadai 13 Kavanthandalam 14 Keelambi 15 Kilar 16 Keelkadirpur 17 Keelperamanallur 18 Kolivakkam 19 Konerikuppam 20 Kuram 21 Magaral 22 Melkadirpur 23 Melottivakkam 24 Musaravakkam 25 Muthavedu 26 Muttavakkam 27 Narapakkam 28 Nathapettai 29 Olakkolapattu 30 Orikkai 31 Perumbakkam 32 Punjarasanthangal 33 Putheri 34 Sirukaveripakkam 35 Sirunaiperugal 36 Thammanur 37 Thenambakkam 38 Thimmasamudram 39 Thilruparuthikundram 40 Thirupukuzhi List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 41 Valathottam 42 Vippedu 43 Vishar 2 Walajabad 1 Agaram 2 Alapakkam 3 Ariyambakkam 4 Athivakkam 5 Attuputhur 6 Aymicheri 7 Ayyampettai 8 Devariyambakkam 9 Ekanampettai 10 Enadur 11 Govindavadi 12 Illuppapattu 13 Injambakkam 14 Kaliyanoor 15 Karai 16 Karur 17 Kattavakkam 18 Keelottivakkam 19 Kithiripettai 20 Kottavakkam 21 Kunnavakkam 22 Kuthirambakkam 23 Marutham 24 Muthyalpettai 25 Nathanallur 26 Nayakkenpettai 27 Nayakkenkuppam 28 Olaiyur 29 Paduneli 30 Palaiyaseevaram 31 Paranthur 32 Podavur 33 Poosivakkam 34 Pullalur 35 Puliyambakkam 36 Purisai List of Village Panchayats in Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name Village Code Village Panchayat Name 37 -

District Survey Report of Madurai District

Content 1.0 Preamble ................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................ 2 3.0 Overview of Mining Activity In The District .............................................................. 3 4.0 List of Mining Leases details ................................................................................... 5 5.0 Details of the Royalty or Revenue received in last Three Years ............................ 36 6.0 Details of Production of Sand or Bajri Or Minor Minerals In Last Three Years ..... 36 7.0 Process of deposition of Sediments In The River of The District ........................... 36 8.0 General Profile of Maduari District ....................................................................... 27 8.1 History ............................................................................................................. 28 8.2 Geography ....................................................................................................... 28 8.3 Taluk ................................................................................................................ 28 8.2 Blocks .............................................................................................................. 29 9.0 Land Utilization Pattern In The -

9.-Mr.V.Manimaran.Pdf

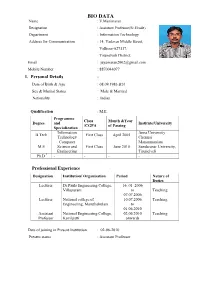

BIO DATA Name : V.Manimaran Designation : Assistant Professor(Sr.Grade) Department : Information Technology Address for Communication : 14, Yadavar Middle Street, Vallioor-627117. Tirunelveli District. Email : [email protected] Mobile Number : 8870044077 1. Personal Details : Date of Birth & Age : 08.09.1983 &31 Sex & Marital Status : Male & Married Nationality : Indian Qualification : M.E. Programme Class Month &Year Degree and Institute/University /CGPA of Passing Specialization Information Anna University B.Tech First Class April 2005 Technology Chennai Computer Manonmaniam M.E Science and First Class June 2010 Sundaranar University, Engineering Tirunelveli Ph.D * - - - - Professional Experience : Designation Institution/ Organisation Period Nature of Duties Lecturer Dr.Pauls Engineering College, 16 .01 .2006 Villupuram. to Teaching 07.07.2006 Lecturer National college of 10.07.2006 Teaching Engineering, Maruthakulam. to 01.06.2010 Assistant National Engineering College, 02.06.2010 Teaching Professor Kovilpatti onwards Date of joining in Present Institution : 02-06-2010 Present status : Assistant Professor Courses taught: Course Title U.G. or P.G. 1. Computer Graphics 2. Database Management Systems 3. Data Structures 4. Information Coding Techniques U.G 5. Object Oriented Analysis and Design 6. System Software 7. Total Quality Management 8. Principles of Management 1. Unix Programming 2. Principles of Object Oriented System P.G 3. Advanced Operating Systems 2. Academic Achievements 2.1 Short term Courses / Seminars / Conference/ Workshops organized: S.No Programme Dates Responsibility 1 Two days Workshop on Digital Image 11.02.2011 Coordinator Processing Using MATLAB to 12.02.2011 2 One Day National Conference- ENIAC’12 12.10.2012 Coordinator 2.2 Short term Courses / Seminars / Conference/ Workshops Attended: Sno Title Programme Date Venue Data Base 11.06.2007 to SSN College of 1. -

Golden Research Thoughts

GRT Golden ReseaRch ThouGhTs ISSN: 2231-5063 Impact Factor : 4.6052 (UIF) Volume - 6 | Issue - 7 | January – 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________________ RAMANATHAPURAM : PAST AND PRESENT- A BIRD’S EYE VIEW Dr. A. Vadivel Department of History , Presidency College , Chennai , Tamil Nadu. ABSTRACT The present paper is an attempt to focus the physical features, present position and past history of the Ramnad District which was formed in the tail end of the Eighteenth Century. No doubt, the Ramnad District is the oldest district among the districts of the erstwhile Madras Presidency and the present Tamil Nadu. The District was formed by the British with the aim to suppress the southern poligars of the Tamil Country . For a while the southern poligars were rebellious against the expansion of the British hegemony in the south Tamil Country. After the formation of the Madras Presidency , this district became one of its districts. For sometimes it was merged with Madurai District and again its collectorate was formed in 1910. In the independent Tamil Nadu, it was trifurcated into Ramnad, Sivagangai and Viudhunagar districts. The district is, historically, a unique in many ways in the past and present. It was a war-torn region in the Eighteenth Century and famine affected region in the Nineteenth Century, and a region known for the rule of Setupathis. Many freedom fighters emerged in this district and contributed much for the growth of the spirit of nationalism. KEY WORDS : Ramanathapuram, Ramnad, District, Maravas, Setupathi, British Subsidiary System, Doctrine of Lapse ,Dalhousie, Poligars. INTRODUCTION :i Situated in the south east corner of Tamil Nadu State, Ramanathapuram District is highly drought prone and most backward in development. -

Top 300 Masters 2020

TOP 300 MASTERS 2020 2020 Top 300 MASTERS 1 About Broadcom MASTERS Broadcom MASTERS® (Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering for Rising Stars), a program of Society for Science & the Public, is the premier middle school science and engineering fair competition, inspiring the next generation of scientists, engineers and innovators who will solve the grand challenges of the 21st century and beyond. We believe middle school is a critical time when young people identify their personal passion, and if they discover an interest in STEM, they can be inspired to follow their passion by taking STEM courses in high school. Broadcom MASTERS is the only middle school STEM competition that leverages Society- affiliated science fairs as a critical component of the STEM talent pipeline. In 2020, all 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students around the country who were registered for their local or state Broadcom MASTERS affiliated fair were eligible to compete. After submitting the online application, the Top 300 MASTERS are selected by a panel of scientists, engineers, and educators from around the nation. The Top 300 MASTERS are honored for their work with a $125 cash prize, through the Society’s partnership with the U.S. Department of Defense as a member of the Defense STEM education Consortium (DSEC). Top 300 MASTERS also receive a prize package that includes an award ribbon, a Top 300 MASTERS certificate of accomplishment, a Broadcom MASTERS backpack, a Broadcom MASTERS decal, a one-year family digital subscription to Science News magazine, an Inventor's Notebook, courtesy of The Lemelson Foundation, a one-year subscription to Wolfram Mathematica software, courtesy of Wolfram Research, and a special prize from Jeff Glassman, CEO of Covington Capital Management. -

Irrigation Infrastructure – 21 Achievements During the Last Three Years

INDEX Sl. Subject Page No. 1. About the Department 1 2. Historic Achievements 13 3. Irrigation infrastructure – 21 Achievements during the last three years 4. Tamil Nadu on the path 91 of Development – Vision 2023 of the Hon’ble Chief Minister 5. Schemes proposed to be 115 taken up in the financial year 2014 – 2015 (including ongoing schemes) 6. Inter State water Issues 175 PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT “Ú®ts« bgU»dhš ãyts« bgUF« ãyts« bgU»dhš cyf« brê¡F«” - kh©òäF jäœehL Kjyik¢r® òu£Á¤jiyé m«kh mt®fŸ INTRODUCTION: Water is the elixir of life for the existence of all living things including human kind. Water is essential for life to flourish in this world. Therefore, the Great Poet Tiruvalluvar says, “ڮϋW mikahJ cybfå‹ ah®ah®¡F« th‹Ï‹W mikahJ xG¡F” (FwŸ 20) (The world cannot exist without water and order in the world can exists only with rain) Tamil Nadu is mainly dependent upon Agriculture for it’s economic growth. Hence, timely and adequate supply of “water” is an important factor. Keeping the above in mind, I the Hon’ble Chief Minister with her vision and intention, to make Tamil Nadu a “numero uno” State in the country with “Peace, Prosperity and Progress” as the guiding principle, has been guiding the Department in the formulation and implementation of various schemes for the development and maintenance of water resources. On the advice, suggestions and with the able guidance of Hon’ble Chief Minister, the Water Resources Department is maintaining the Water Resources Structures such as, Anicuts, Tanks etc., besides rehabilitating and forming the irrigation infrastructure, which are vital for the food production and prosperity of the State. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Persistence of Caste in South India - an Analytical Study of the Hindu and Christian Nadars

Copyright by Hilda Raj 1959 , PERSISTENCE OF CASTE IN SOUTH INDIA - AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE HINDU AND CHRISTIAN NADARS by Hilda Raj Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Signatures of Committee: . Chairman: D a t e ; 7 % ^ / < f / 9 < r f W58 7 a \ The American University Washington, D. 0. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply thankful to the following members of my Dissertation Committee for their guidance and sug gestions generously given in the preparation of the Dissertation: Doctors Robert T. Bower, N. G. D. Joardar, Lawrence Krader, Harvey C. Moore, Austin Van der Slice (Chairman). I express my gratitude to my Guru in Sociology, the Chairman of the above Committee - Dr. Austin Van der Slice, who suggested ways for the collection of data, and methods for organizing and presenting the sub ject matter, and at every stage supervised the writing of my Dissertation. I am much indebted to the following: Dr. Horace Poleman, Chief of the Orientalia Di vision of the Library of Congress for providing facilities for study in the Annex of the Library, and to the Staff of the Library for their unfailing courtesy and readi ness to help; The Librarian, Central Secretariat-Library, New Delhi; the Librarian, Connemara Public Library, Madras; the Principal in charge of the Library of the Theological Seminary, Nazareth, for privileges to use their books; To the following for helping me to gather data, for distributing questionnaire forms, collecting them after completion and mailing them to my address in Washington: Lawrence Gnanamuthu (Bombay), Dinakar Gnanaolivu (Madras), S. -

Agastya International Foundation Synopsys

In Partnership with Student Projects Technical Record Released on the occasion of Science & Engineering Fair of Selected Projects at Shikshakara Sadana, K G Road Bangalore on th th th 26 , 27 & 28 February 2018 Organised by Agastya International Foundation In support with Synopsys Anveshana 2017-18- BANGALORE - Abstract Book Page 1 of 209 CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD 2. ABOUT AGASTYA INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION 3. ABOUT SYNOPSYS 4. ABOUT ANVESHANA 5. PROJECT SCREENING COMMITTEE 6. COPY OF INVITATION 7. PROGRAM CHART 8. LIST OF PROJECTS EXHIBITED IN THE FAIR 9. PROJECT DESCRIPTION Anveshana 2017-18- BANGALORE - Abstract Book Page 2 of 209 FOREWORD In a world where recent events suggest that we may be entering a period of greater uncertainties, it is disturbing that India's educational system is not (in general) internationally competitive. In an age where the state of the economy is driven more and more by knowledge and skill, it is clear that the future of our country will depend crucially on education at all levels – from elementary schools to research universities. It is equally clear that the question is not one of talent or innate abilities of our country men, as more and more Indians begin to win top jobs in US business and industry, government and academia. Indian talent is almost universally acknowledged, as demonstrated by the multiplying number of R&D centres being set up in India by an increasing number of multinational companies. So what is the real problem? There are many problems ranging from poor talent management to an inadequate teaching system in most schools and colleges where there is little effort to make contact with the real world in general rather than only prescribed text books. -

Revenue Department Policy Note 2010-2011 I. Periasamy

REVENUE DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE 2010-2011 Demand No.41 - Revenue Department Demand No.51 - Relief on Account of Natural Calamities I. PERIASAMY MINISTER FOR REVENUE AND HOUSING © Government of Tamil Nadu 2010 REVENUE DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE 2010-2011 REVENUE DEPARTMENT POLICY NOTE 2010-2011 Index Chapter Contents Pages No. I Introduction 1-5 II Revenue Administration, Disaster Management and Mitigation Department 1. Revenue Administration 7-15 2. Social security schemes 15-20 3. Redressal of Public Grievances 20-25 4. Natural Calamities and Disaster 25-40 Management III Land Administration 1. Land Assignment 41-47 2. Land Lease, Transfer & Alienation 48-51 3. Eviction of Encroachments 51-53 4. Land Acquisition 53-56 IV Survey & Settlement 1. Survey 57-64 2. Settlement 64-68 V Land Reforms 1. Land Reforms and Ceiling 69-74 2. Tenancy Laws 75-79 3. Tamil Nadu Agricultural Labourers 79-83 Welfare Board 4. Urban Land Ceiling & Urban Land Tax 83-90 CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTION The Land Revenue had been the main source of revenue for the State since the Sangam age. The Land tax had been levied based on the type of the Land and the crop yield. At times, when the land tax was levied exorbitantly the scholars and the poets had played the advisory role by pointing out the defects to the King and had set the Government on the right path. It is pertinent to note that even in the Sangam age, the poet Piciranthaiyar had given advice to the Pandia King Arivudai Nambi about the taxation system in his poem in 'Pura Nanuru' Cut the paddy corn When it is ripe, And make it into balls of rice, And the yield of a small field, Barely a fraction of a cent, Will feed an elephant For many a day 2 But if the brute Should step into a field, And trampling eat, Even a hundred acres Will not serve, For the feet will spoil More than the mouth could eat. -

Chapter 4.1.9 Ground Water Resources Theni District

CHAPTER 4.1.9 GROUND WATER RESOURCES THENI DISTRICT 1 INDEX CHAPTER PAGE NO. INTRODUCTION 3 THENI DISTRICT – ADMINISTRATIVE SETUP 3 1. HYDROGEOLOGY 3-7 2. GROUND WATER REGIME MONITORING 8-15 3. DYNAMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES 15-24 4. GROUND WATER QUALITY ISSUES 24-25 5. GROUND WATER ISSUES AND CHALLENGES 25-26 6. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT AND REGULATION 26-32 7. TOOLS AND METHODS 32-33 8. PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 33-36 9. REFORMS UNDERTAKEN/ BEING UNDERTAKEN / PROPOSED IF ANY 10. ROAD MAPS OF ACTIVITIES/TASKS PROPOSED FOR BETTER GOVERNANCE WITH TIMELINES AND AGENCIES RESPONSIBLE FOR EACH ACTIVITY 2 GROUND WATER REPORT OF THENI DISTRICT INRODUCTION : In Tamil Nadu, the surface water resources are fully utilized by various stake holders. The demand of water is increasing day by day. So, groundwater resources play a vital role for additional demand by farmers and Industries and domestic usage leads to rapid development of groundwater. About 63% of available groundwater resources are now being used. However, the development is not uniform all over the State, and in certain districts of Tamil Nadu, intensive groundwater development had led to declining water levels, increasing trend of Over Exploited and Critical Firkas, saline water intrusion, etc. ADMINISTRATIVE SET UP The geographical extent of Theni District is 3, 24,230 hectares or 3,242.30 sq.km. Accounting for 2.05 percent of the geographical area of Tamilnadu State. The district has well laid roads and railway lines connecting all major towns within and outside the State. For administrative purpose, the district has been bifurcated into 5 Taluks, 8 Blocks and 17 Firkas . -

District Statistical Handbook 2018-19

DISTRICT STATISTICAL HANDBOOK 2018-19 DINDIGUL DISTRICT DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF STATISTICS DISTRICT STATISTICS OFFICE DINDIGUL Our Sincere thanks to Thiru.Atul Anand, I.A.S. Commissioner Department of Economics and Statistics Chennai Tmt. M.Vijayalakshmi, I.A.S District Collector, Dindigul With the Guidance of Thiru.K.Jayasankar M.A., Regional Joint Director of Statistics (FAC) Madurai Team of Official Thiru.N.Karuppaiah M.Sc., B.Ed., M.C.A., Deputy Director of Statistics, Dindigul Thiru.D.Shunmuganaathan M.Sc, PBDCSA., Divisional Assistant Director of Statistics, Kodaikanal Tmt. N.Girija, MA. Statistical Officer (Admn.), Dindigul Thiru.S.R.Arulkamatchi, MA. Statistical Officer (Scheme), Dindigul. Tmt. P.Padmapooshanam, M.Sc,B.Ed. Statistical Officer (Computer), Dindigul Selvi.V.Nagalakshmi, M.Sc,B.Ed,M.Phil. Assistant Statistical Investigator (HQ), Dindigul DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK 2018-19 PREFACE Stimulated by the chief aim of presenting an authentic and overall picture of the socio-economic variables of Dindigul District. The District Statistical Handbook for the year 2018-19 has been prepared by the Department of Economics and Statistics. Being a fruitful resource document. It will meet the multiple and vast data needs of the Government and stakeholders in the context of planning, decision making and formulation of developmental policies. The wide range of valid information in the book covers the key indicators of demography, agricultural and non-agricultural sectors of the District economy. The worthy data with adequacy and accuracy provided in the Hand Book would be immensely vital in monitoring the district functions and devising need based developmental strategies. It is truly significant to observe that comparative and time series data have been provided in the appropriate tables in view of rendering an aerial view to the discerning stakeholding readers.