La Dolce Vita" Today: Fashion and Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

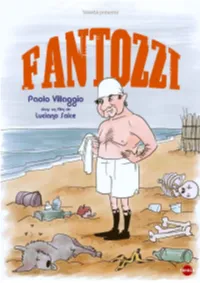

Ce N'est Pas À Moi De Dire Que Fantozzi Est L'une Des Figures Les Plus

TAMASA présente FANTOZZI un film de Luciano Salce en salles le 21 juillet 2021 version restaurée u Distribution TAMASA 5 rue de Charonne - 75011 Paris [email protected] - T. 01 43 59 01 01 www.tamasa-cinema.com u Relations Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] - 06 10 37 16 00 Fantozzi est un employé de bureau basique et stoïque. Il est en proie à un monde de difficultés qu’il ne surmonte jamais malgré tous ses efforts. " Paolo Villaggio a été le plus grand clown de sa génération. Un clown immense. Et les clowns sont comme les grands poètes : ils sont rarissimes. […] N’oublions pas qu’avant lui, nous avions des masques régionaux comme Pulcinella ou Pantalone. Avec Fantozzi, il a véritablement inventé le premier grand masque national. Quelque chose d’éternel. Il nous a humiliés à travers Ugo Fantozzi, et corrigés. Corrigés et humiliés, il y a là quelque chose de vraiment noble, n’est-ce pas ? Quelque chose qui rend noble. Quand les gens ne sont plus capables de se rendre compte de leur nullité, de leur misère ou de leurs folies, c’est alors que les grands clowns apparaissent ou les grands comiques, comme Paolo Villaggio. " Roberto Benigni " Ce n’est pas à moi de dire que Fantozzi est l’une des figures les plus importantes de l’histoire culturelle italienne mais il convient de souligner comment il dénonce avec humour, sans tomber dans la farce, la situation de l’employé italien moyen, avec des inquiétudes et des aspirations relatives, dans une société dépourvue de solidarité, de communication et de compassion. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Touching Textures Through the Screen: a Cinematic Investigation of the Contemporary Fashion Film

Touching Textures Through the Screen: A Cinematic Investigation of the Contemporary Fashion Film Name: Simone Houg Supervisor: Dr. M.A.M.B Baronian Student Number: Second Reader: Dr. F.J.J.W. Paalman Address: University of Amsterdam Master Thesis Film Studies Phone Number: 26 June 2015 Email: [email protected] Word Count: 23709 2 Abstract The contemporary fashion film emerged at the beginning of this century and has enabled fashion and film to enter into an equivalent relationship. This symbiotic relationship goes back to the emergence of both disciplines at the beginning of the twentieth century. The fashion film is a relatively new phenomenon that is presented on the Internet as a short film, made by fashion designers and fashion houses that optionally collaborate with well-known filmmakers. The fashion film expresses itself in many forms and through many different styles and characteristics, which makes it hard to grasp. In the case studies on the fashion films commissioned by Dior, Prada, Hussein Chalayan and Maison Margiela, concepts such as colour, movement and haptic visuality are investigated, in order to demonstrate that by focusing on the fashion films' similar use of these cinematic techniques, a definition of the fashion film can be constituted. The fashion film moves in our contemporary society; a society that is focused on ideas of progress, increased mobility and other concepts that characterise a culture of modernity. These concepts evoke feelings of nostalgia and the fashion film responds to this by immersing the spectator into a magical, fictionalised world full of desired garments, objects and settings. The ‘aura’ that surrounds the fashion brand is expressed by letting the viewer fully participate in this fashioned world. -

From the Villa of the Sette Bassi to the Park of the Aqueducts

From the Villa of the Sette Bassi to the Park of the Aqueducts Park of the Aqueduts This itinerary, which uses the city roads, leads to a beautiful green area crossed by no less than six Roman aqueducts, as well as one built in the Renaissance period. Beginning at the Villa of the Sette Bassi and taking the via Tuscolana northwards you come to Italy’s Hollywood, the film studios at Cinecittà and the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, a film school established in the 1930s, for which the Tuscolano neighbourhood was famous. Continuing on the Circonvallazione Tuscolana to the junction with via Lemonia you reach one POI Distance of the entrances to the Park of the Aqueducts, with the impressive arches of the aqua Claudia 4 2.03 Km and aqua Anio novus aqueducts, superimposed, and the remains of the aqua Marcia, aqua Tepula and aqua Iulia. Here you can also admire the fascinating Romavecchia farmhouse, dating back to the Middle Poi Ages when this part of the countryside was called Old Rome. The area was crossed in antiquity by one of the great consular roads, the Via Latina, which ran almost parallel to the Appian Way southwards. A stroll through the Roman countryside, dotted with ancient ruins, 1 Villa of the Sette Bassi (Tuscolana) takes you to the nearby park of Tor Fiscale. 2 The Cinecittà Film Studios 3 Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Experimental Film Centre (CSC) 4 Park of the Aqueducts (Via Lemonia) Scan the QrCode to access the navigable mobile version of the itinerary Poi 1 Villa of the Sette Bassi (Tuscolana) Roma / Place to visit - Archaeological areas The so-called Villa of the Sette Bassi is one of the largest villas in the Rome suburbs, indeed, the second-largest after that of the Quintilii. -

Kate Moss Ebook

KATE MOSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mario Testino | 232 pages | 15 Apr 2014 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836550697 | English | Cologne, Germany Kate Moss PDF Book The statue is said to be the largest gold statue to be created since the era of Ancient Egypt. She appeared in the closing ceremony for the Summer Olympics in London. More top stories. Retrieved 23 August Getty Images. Archived from the original on 11 March Industry sources reported that Kate's priorities have shifted from her own career to launching her only daughter onto the fashion scene. Homeless migrants will be deported and criminals from EU countries will be banned under tough new The pair, who both hail from South London, were often seen hanging out together in public and at events. The SamandRuby organisation is named after a friend of Moss's, Samantha Archer Fayet, and her 6-month-old daughter Ruby Rose who were killed by the tsunami while visiting Thailand. Retrieved on 7 December The London native has been a trailblazer in the fashion industry over the years, becoming one of the shortest models to walk the runways, standing at 5'7". This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. Archived from the original on 10 September She appeared on the cover of a British magazine the next year, which was her first cover shot and an important career milestone for any model. Sky News. By the next year, she had a slew of new modeling contracts with companies, such as Calvin Klein and Burberry, which had dropped her at the time of the drug scandal. -

Final Thesis

AN EXAMINATION OF INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN ITALIAN AND AMERICAN FASHION CULTURES: PAST, PRESENT, AND PROJECTIONS FOR THE FUTURE BY: MARY LOUISE HOTZE TC 660H PLAN II HONORS PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN MAY 10, 2018 ______________________________ JESSICA CIARLA DEPARTMENT OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL SUPERVISING PROFESSOR ______________________________ ANTONELLA DEL FATTORE-OLSON DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH AND ITALIAN SECOND READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………………………………… 3 Acknowledgements………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………..……….. 4 Introduction………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………………….…….…. 5 Part 1: History of Italian Fashion……...……...……..……...……...……...……...……...……...……...... 9 – 47 AnCiEnt Rome and thE HoLy Roman EmpirE…………………………………………………….……….…... 9 ThE MiddLE AgEs………………………………………….……………………………………………………….…….. 17 ThE REnaissanCE……………………………………….……………………………………………………………...… 24 NeoCLassism to RomantiCism……………………………………….…………………………………….……….. 32 FasCist to REpubLiCan Italy……………………………………….…………………………………….……………. 37 Part 2: History of American Fashion…………………………………………….……………………………… 48 – 76 ThE ColoniaL PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………………………………. 48 ThE IndustriaL PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………………………….…. 52 ThE CiviL War and Post-War PEriod……………………………………….……………………………………. 58 ThE EarLy 20th Century……………………………………….………………………………………………….……. 63 ThE Mid 20th Century……………………………………….…………………………………………………………. 67 ThE LatE 20th Century……………………………………….………………………………………………………… 72 Part 3: Discussion of Individual -

(QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands

November 9, 2016 Xcel Brands, Inc. Quick Time Response (QTR) Apparel Program Supercharges Licensing in Complementary Categories Across Isaac Mizrahi, H Halston, and Judith Ripka Brands NEW YORK, Nov. 09, 2016 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Xcel Brands, Inc. (NASDAQ:XELB) is pleased to announce multiple new licenses across its owned brands as licensees look to pursue growth in categories complementary to Xcel's successful quick time response (QTR) apparel programs at Lord & Taylor and Hudson's Bay stores. CEO and Chairman of Xcel Brands, Inc. Robert W. D'Loren remarked, "With the rise of a ‘see-now-buy-now' consumer shopping mentality and the need to respond to trends as they happen, Xcel created an innovative solution to bring exclusive brands to our department store partners in a quick time response format. The rapid growth of these apparel programs has generated excitement within the licensing community across numerous complementary categories. With these new partnerships we will continue to build meaningful lifestyle brands under the IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi and H Halston labels." New licensees under the Isaac Mizrahi brand include tech accessories and luggage, with product set to retail in Spring 2017. Xcel Brands, Inc. entered into a licensing agreement with Bytech NY Inc. for tech accessories for smartphones, PCs, tablets, and personal audio across the Isaac Mizrahi New York, IMNYC Isaac Mizrahi, and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. Xcel also entered into a licensing agreement with Longlat Inc. for a collection of hard and soft luggage under the Isaac Mizrahi New York and Isaac Mizrahi Live! labels. New licensees under the H Halston brand include sleepwear and intimates, legwear and slippers, and non-optical sunglasses and readers. -

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 Min)

October 5, 2010 (XXI:6) Federico Fellini, 8½ (1963, 138 min) Directed by Federico Fellini Story by Federico Fellini & Ennio Flaiano Screenplay by Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Federico Fellini & Brunello Rondi Produced by Angelo Rizzoli Original Music by Nino Rota Cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo Film Editing by Leo Cattozzo Production Design by Piero Gherardi Art Direction by Piero Gherardi Costume Design by Piero Gherardi and Leonor Fini Third assistant director…Lina Wertmüller Academy Awards for Best Foreign Picture, Costume Design Marcello Mastroianni...Guido Anselmi Claudia Cardinale...Claudia Anouk Aimée...Luisa Anselmi Sandra Milo...Carla Hazel Rogers...La negretta Rossella Falk...Rossella Gilda Dahlberg...La moglie del giornalista americano Barbara Steele...Gloria Morin Mario Tarchetti...L'ufficio di stampa di Claudia Madeleine Lebeau...Madeleine, l'attrice francese Mary Indovino...La telepata Caterina Boratto...La signora misteriosa Frazier Rippy...Il segretario laico Eddra Gale...La Saraghina Francesco Rigamonti...Un'amico di Luisa Guido Alberti...Pace, il produttore Giulio Paradisi...Un'amico Mario Conocchia...Conocchia, il direttore di produzione Marco Gemini...Guido da ragazzo Bruno Agostini...Bruno - il secundo segretario di produzione Giuditta Rissone...La madre di Guido Cesarino Miceli Picardi...Cesarino, l'ispettore di produzione Annibale Ninchi...Il padre di Guido Jean Rougeul...Carini, il critico cinematografico Nino Rota...Bit Part Mario Pisu...Mario Mezzabotta Yvonne Casadei...Jacqueline Bonbon FEDERICO FELLINI -

Italian Fashion & Innovation

Italian Fashion & Innovation Derek Pante Azmina Karimi Morgan Taylor Russell Taylor Introduction In Spring 2008, the Italia Design team researched the fashion industry in Italy, and discussed briefly how it fits into Italy’s overall innovation. The global public’s perception of Italy and Italian Design rests to some degree on the visibility and success of Fashion Design. The fashion and design industries account for a large percentage of Milan’s total economic output— as Milan goes economically, so goes Italy (Foot, 2001). Fashion Design clearly contributes to “brand Italia,” as well as to Italian culture generally. Yet, fashion is not our focus in this study: innovation and design is. Fashion’s goals are not the same as design. For one, fashion operates on “style,” design works on “language,” and style to a serious designer is usually the opposite of good design. Yet to ignore the area possibly creates a blind spot. With the resource this year of some students with great interest in this area it was decided that we should begin to investigate how fashion in Italy contributes to innovation, and how fashion in Milan and other centers in the North of Italy sustain “Creative Centers” where measurable agglomeration (a sign of innovation) occurs. Delving into Italian Fashion allowed us to rethink certain paradigms. For one, how we look at Florence as a design center. Florence has very little Industrial Design and, because of the city’s UNESCO World Heritage designation, has very little contemporary architectural culture. This reality became clear after four years of returning to the Renaissance city. -

Marcas E Editoriais De Moda Em Diferentes Nichos De Revistas Especializadas

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas O caso Vogue, i-D e Dazed & Confused Joana Miguel Ramires Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Design de Moda (2º ciclo de estudos) Orientador: Prof. Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira Covilhã, Outubro de 2012 Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas II Marcas e Editoriais de Moda em Diferentes Nichos de Revistas Especializadas Agradecimentos Ao longo do percurso que resultou na realização deste trabalho, foram várias as pessoas que ajudaram a desenvolve-lo e que disponibilizaram o seu apoio e amizade. Desta forma, o primeiro agradecimento vai para a orientadora, Professora Doutora Maria Madalena Rocha Pereira, que desde o início foi incansável. Agradeço-lhe pela disponibilidade, compreensão, por me ter guiado da melhor forma por entre todas as dúvidas e problemas que foram surgindo, e por fim, pela força de vontade e entusiamo que me transmitiu. A todos os técnicos e colaboradores dos laboratórios e ateliês do departamento de engenharia têxtil da Universidade da Beira Interior agradeço o seu apoio e os ensinamentos transmitidos ao longo da minha vida académica. Agradeço em especial á D. Lucinda pela sua amizade, e pelo seu apoio constante ao longo destes anos. Às duas pessoas mais importantes da minha vida, pai e mãe agradeço do fundo do coração por todo o amor, carinho, compreensão, e por todos os sacrifícios que fizeram, de modo a me permitirem chegar ao final de mais esta etapa de estudos. Aos meus avós e restante família que também têm sido um pilar fundamental na minha vida a todos os níveis, os meus sinceros agradecimentos.