Defensive Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creditors' Challenges to Administrators and Liquidators

CREDITORS’ CHALLENGES TO ADMINISTRATORS AND LIQUIDATORS – AN OVERVIEW REPRINTED FROM: CORPORATE DISPUTES MAGAZINE OCT-DEC 2018 ISSUE ���������corporate ��������disputes ������������ C��D www.corporatedisputesmagazine.com ������������������ ������� ������������������������������� ������������ �������������������� ��������� ����������������������������� ���������������������� ����������������� www.corporatedisputesmagazine.com Visit the website to request a free copy of the full e-magazine Published by Financier Worldwide Ltd corporatedisputes@financierworldwide.com © 2018 Financier Worldwide Ltd. All rights reserved. corporate CDdisputes www.corporatedisputesmagazine.com 2 CORPORATE DISPUTES Oct-Dec 2018 www.corporatedisputesmagazine.com PERSPECTIVES PERSPECTIVES CREDITORS’ CHALLENGES TO ADMINISTRATORS AND LIQUIDATORS – AN OVERVIEW BY ASHKHAN CANDEY, NICK WRIGHT AND JAMES PARTRIDGE > CANDEY nsolvency practitioners occupy a powerful and was simply wrong, with the Court also having a responsible role in administrations and liquidations. general ability to interfere where office holders have IThey are often a major force for good, tackling misapplied the law as Neuberger J, as he then was, those who have raided companies for their own made clear in CE King Ltd. personal benefit to the unlawful detriment of creditors As well as being the arbiter of their decisions at law, and shareholders. Their decisions may be based on a the court also has an inherent jurisdiction to control misunderstanding of the law, and they could (rarely) administrators -

Bankrupt Subsidiaries: the Challenges to the Parent of Legal Separation

ERENSFRIEDMAN&MAYERFELD GALLEYSFINAL 1/27/2009 10:25:46 AM BANKRUPT SUBSIDIARIES: THE CHALLENGES TO THE PARENT OF LEGAL SEPARATION ∗ Brad B. Erens ∗∗ Scott J. Friedman ∗∗∗ Kelly M. Mayerfeld The financial distress of a subsidiary can be a difficult event for its parent company. When the subsidiary faces the prospect of a bankruptcy filing, the parent likely will need to address many more issues than simply its lost investment in the subsidiary. Unpaid creditors of the subsidiary instinctively may look to the parent as a target to recover on their claims under any number of legal theories, including piercing the corporate veil, breach of fiduciary duty, and deepening insolvency. The parent also may find that it has exposure to the subsidiary’s creditors under various state and federal statutes, or under contracts among the parties. In addition, untangling the affairs of the parent and subsidiary, if the latter is going to reorganize under chapter 11 and be owned by its creditors, can be difficult. All of these issues may, in fact, lead to financial challenges for the parent itself. Parent companies thus are well advised to consider their potential exposure to a subsidiary’s creditors not only once the subsidiary actually faces financial distress, but well in advance as a matter of prudent corporate planning. If a subsidiary ultimately is forced to file for chapter 11, however, the bankruptcy laws do provide unique procedures to resolve any existing or potential litigation between the parent and the subsidiary’s creditors and to permit the parent to obtain a clean break from the subsidiary’s financial problems. -

Contracting out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: the Main Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 In

Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 12 2014 Contracting Out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: The ainM Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 in the Proposal to Amend the EU Insolvency Regulation Bob Wessels Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl Recommended Citation Bob Wessels, Contracting Out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: The Main Liquidator's Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 in the Proposal to Amend the EU Insolvency Regulation, 9 Brook. J. Corp. Fin. & Com. L. (2014). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjcfcl/vol9/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of Corporate, Financial & Commercial Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. CONTRACTING OUT OF SECONDARY INSOLVENCY PROCEEDINGS: THE MAIN LIQUIDATOR’S UNDERTAKING IN THE MEANING OF ARTICLE 18 IN THE PROPOSAL TO AMEND THE EU INSOLVENCY REGULATION Prof. Dr. Bob Wessels* INTRODUCTIOn The European Insolvency Regulation1 aims to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of insolvency proceedings having cross-border effects within the European Union. For that purpose, the Insolvency Regulation lays down rules on jurisdiction common to all member states of the European Union (Member States), rules to facilitate recognition of insolvency judgments, and rules regarding the applicable law. The model of the Regulation will be known. It allows for one main proceeding, opened in one Member State, with the possibility of opening secondary proceedings in other EU Member States. The procedural model can only be successful if these proceedings are coordinated: Main insolvency proceedings and secondary proceedings can…contribute to the effective realization of the total assets only if all the concurrent proceedings pending are coordinated. -

Restructuring & Insolvency

GETTING THROUGH THE DEAL Restructuring & Insolvency Restructuring & Insolvency Restructuring Contributing editor Bruce Leonard 2017 2017 © Law Business Research 2016 Restructuring & Insolvency 2017 Contributing editor Bruce Leonard The International Insolvency Institute Publisher Law The information provided in this publication is Gideon Roberton general and may not apply in a specific situation. [email protected] Business Legal advice should always be sought before taking Research any legal action based on the information provided. Subscriptions This information is not intended to create, nor does Sophie Pallier Published by receipt of it constitute, a lawyer–client relationship. [email protected] Law Business Research Ltd The publishers and authors accept no responsibility 87 Lancaster Road for any acts or omissions contained herein. The Senior business development managers London, W11 1QQ, UK information provided was verified between Alan Lee Tel: +44 20 3708 4199 September and October 2016. Be advised that this is [email protected] Fax: +44 20 7229 6910 a developing area. Adam Sargent © Law Business Research Ltd 2016 [email protected] No photocopying without a CLA licence. Printed and distributed by First published 2008 Encompass Print Solutions Dan White Tenth edition Tel: 0844 2480 112 [email protected] ISSN 2040-7408 © Law Business Research 2016 CONTENTS Global overview 7 Cyprus 129 Richard Tett Lia Iordanou Theodoulou, Angeliki Epaminonda -

Uniform Commercial Real Estate Receivership Act

UNIFORM COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE RECEIVERSHIP ACT drafted by the NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS and by it APPROVED AND RECOMMENDED FOR ENACTMENT IN ALL THE STATES at its ANNUAL CONFERENCE MEETING IN ITS ONE-HUNDRED-AND-TWENTY-FOURTH YEAR WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA JULY 10 - JULY 16, 2015 WITH PREFATORY NOTE AND COMMENTS Copyright © 2015 By NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS September 22, 2015 ABOUT ULC The Uniform Law Commission (ULC), also known as National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (NCCUSL), now in its 124th year, provides states with non-partisan, well-conceived and well-drafted legislation that brings clarity and stability to critical areas of state statutory law. ULC members must be lawyers, qualified to practice law. They are practicing lawyers, judges, legislators and legislative staff and law professors, who have been appointed by state governments as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to research, draft and promote enactment of uniform state laws in areas of state law where uniformity is desirable and practical. • ULC strengthens the federal system by providing rules and procedures that are consistent from state to state but that also reflect the diverse experience of the states. • ULC statutes are representative of state experience, because the organization is made up of representatives from each state, appointed by state government. • ULC keeps state law up-to-date by addressing important and timely legal issues. • ULC’s efforts reduce the need for individuals and businesses to deal with different laws as they move and do business in different states. -

Claims Against Insolvency Office-Holders' for Professional

CLAIMS AGAINST INSOLVENCY OFFICE-HOLDERS FOR PROFESSIONAL NEGLIGENCE - BUSH LAWYERS AND HUNTERS Hugh Sims QC and Stefan Ramel, Guildhall Chambers February 2017 The easy part … 1. As any student of the law of tort knows only too well, the basic ingredients of a claim in negligence against another person are (1) a duty of care, (2) a breach of that duty, whether by action or omission, which has (3) caused damage that was (4) foreseeable. In considering the duty of care that a person owes to another, and whether it has been breached, it is also necessary to have regard to 2(a) the precise scope of the duty and 2(b) the standard of care that is expected of the alleged tortfeasor. 2. As any lawyer practising in the field of professional negligence also knows only too well, proving in any given case that a professional has been negligent and successfully obtaining a remedy by way of an award of damages is rarely as simple as proving ingredients (1) to (4) at trial. There are many more subtleties than that, whether they arise from knotty legal issues or deciding between differing competing litigation strategies: a brief glance at the table of contents of Jackson & Powell on Professional Liability, 8th Edition, 2017, is enough to dispel any doubts1. The hard part… Introduction 3. So much for the easy bit. How does all of that apply to insolvency office holders? We start with some terminology, specifically, what is meant by the phrases ‘insolvency office-holder’ or ‘insolvency practitioner’. The Insolvency Act 1986 does not expressly define either phrase. -

Bankruptcy [Ch.69 – 1

BANKRUPTCY [CH.69 – 1 BANKRUPTCY CHAPTER 69 BANKRUPTCY ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PRELIMINARY SECTION 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. 3. Exclusion of companies, etc. PART I ADJUDICATION AND VESTING OF PROPERTY Adjudication 4. Petition for adjudication in bankruptcy. 5. Proceedings in relation to a debtor’s summons. 6. Proceedings on petition. 7. Proceedings if debt of petitioning creditor is contested. 8. Advertisement of order of adjudication. 9. Definition of commencement of bankruptcy. 10. Creditors bound by bankruptcy proceedings. 11. Power after presentation of petition to restrain suits, etc., and appoint receiver. Appointment of Trustee 12. Meeting of creditors for appointment of persons to administer bankrupt’s property. 13. Description of bankrupt’s property divisible amongst creditors. 14. Regulations as to first meeting of creditors. 15. Devolution of property on trustee. 16. Evidence of appointment of trustee. PART II ADMINISTRATION OF PROPERTY General Provisions affecting Administration of Property 17. Conduct of bankrupt. 18. Conduct of trustee and appeal to court against trustee. 19. Regulations as to general meetings of creditors subsequent to first meeting. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– [Original Service 2001] STATUTE LAW OF THE BAHAMAS CH.69 – 2] BANKRUPTCY Dealing with Bankrupt’s Property 20. Possession of property by trustee. 21. Disclaimer as to onerous property 22. Limitation of time for disclaimer. 23. Power of trustee to deal with property. 24. Power to allow bankrupt to manage property. 25. Power of trustee to compromise, etc. 26. Power of trustee to accept composition or general scheme of arrangement. 27. Trustee if counsel and attorney may be paid for services. 28. Trustees to pay money into bank. -

Bankruptcyact

BankruptcyAct http://www.nigeria-law.org/BankruptcyAct.htm Constitution of Nigeria Court of Appeal High Courts Home Page Law Bankruptcy Act Reporting Chapter 30 Laws of the Laws of the Federation of Nigeria 1990 Federation This Act has been amended by Bankruptcy (Amendment) Decree N o 109 of 1992 of Nigeria Legal Education Q&A Arrangement of Rules Supreme Part I Court Jobs at Proceedings from Act of Bankruptcy to discharge Nigeria-law Acts of Bankruptcy 1. Acts of bankruptcy. 2. Bankruptcy notices. 3. Jurisdiction to make receiving order. 4. Conditions on which creditor may 5. Liability of firm to have 6. Powers of Official Receiver petition. receiving order made against it. and duties of debtor on petition being filed. 7. Creditor's petition and order 8. Debtor's petition and order 9. Appearance of Official thereon. thereon. Receiver on petition. 10. Effect of receiving order. 11. Power to appoint interim 12. Power to stay pending receiver. proceedings. 13. Power to appoint special manager. 14. Advertisement of receiving 15. First and other meetings of order. creditors. 16. Debtor's statement of affairs. Public examination of debtor 17. Public examination of debtor. 18. Compositions and schemes of 19. arrangement. Adjudication of bankruptcy 20. Adjudication of bankruptcy where 21. Appointment of trustee. 22. Committee of inspection. composition not accepted or not approved. 23. Power to accept composition or scheme after adjudication. Control over person and property of debtor 24. Duties of debtor as to discovery 25. Arrest of debtor under certain 26. Re-direction of debtor's and realisation of property. circumstances. -

Misfeasance in Public Office: a Very Peculiar Tort

MISFEASANCE IN PUBLIC OFFICE: A VERY PECULIAR TORT MARK ARONSON* [Misfeasance in public office is the common law’s only public law tort, because only public officials can commit it, and they must have acted unlawfully in the sense that they exceeded or misused a public power or position. This article examines who might be treated as a public official for these purposes, and whether the tort might extend to government contractors performing public functions. The article also discusses the tort’s expansion beyond the familiar administrative law context of abuse of public power, to abuse or misuse of public position. Misfeasance tortfeasors must at the very least have been recklessly indifferent as to whether they were exceeding or abusing their public power or position and thereby risking harm. That parallels the mens rea ingredient of the common law’s criminal offence of misconduct in public office, and reflects a further reason for restricting the tort’s coverage to public officials, who must always put their self-interest aside and act in the public interest. Upon proof of the tort’s fault elements, there beckons a damages vista apparently unconstrained by negligence law’s familiar limitations upon claims for purely economic loss. This article questions the capacity of the ‘recklessness’ requirement to constrain claims for indeterminate sums from an indeterminate number of claimants, some of whom may have been only secondary (or even more remote) victims of the public official’s misconduct. Finally, it questions (and finds wanting) the assumption common in Australia that government will not usually be vicariously liable for this tort. -

'Directors' Liability for Fraudulent Phoenix Activity

1 Published in (2014) 14 Journal of Corporate Law Studies 139 DIRECTORS’ LIABILITY FOR FRAUDULENT PHOENIX ACTIVITY – A COMPARISON OF THE AUSTRALIAN AND UNITED KINGDOM APPROACHES By Assoc Professor Helen Anderson* ABSTRACT Fraudulent phoenix activity is a matter of widespread concern in Australia following a 2009 Treasury Paper. While there is broad support for its eradication, there is little agreement on the means by which this may be achieved and a general reluctance to do anything that might adversely affect business. The UK has long had laws specifically designed to deal with phoenix companies that reuse the liquidated company’s name, as well as a vigorous program of director disqualification. This article compares Australia’s existing and proposed laws to those in the UK. The incidence of fraudulent phoenix activity continues to grow in Australia despite corporate and taxation laws that apparently address it and in the absence of some of the characteristics existing in the UK that might nourish it: an active rescue culture and the availability of pre-packaged administrations. The article seeks to draw some conclusions of value to both countries. KEYWORDS Fraudulent phoenix activity, comparison, Australia and United Kingdom, reform proposals A. INTRODUCTION Phoenix activity occurs when a company “dies” but its business survives and is carried on through another company, with the aim of avoiding some or all of its legal obligations. In the United Kingdom, it is known as “phoenix syndrome” or “phoenixism”. This may occur through successor companies or the use of related companies in a corporate group, either through the transfer of an insolvent company’s business to another entity in the group or else the deliberate undercapitalisation of a subsidiary with the intention of quarantining its debts from the activities of the rest of the group. -

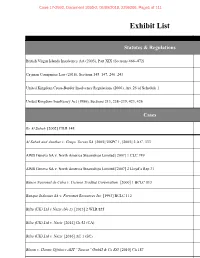

Exhibit List

Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page1 of 111 Exhibit List Statutes & Regulations British Virgin Islands Insolvency Act (2003), Part XIX (Sections 466–472) B Cayman Companies Law (2016), Sections 145–147, 240–243 United Kingdom Cross-Border Insolvency Regulations (2006), Art. 25 of Schedule 1 United Kingdom Insolvency Act (1986), Sections 213, 238–239, 423, 426 Cases Re Al Sabah [2002] CILR 148 Al Sabah and Another v. Grupo Torras SA [2005] UKPC 1, [2005] 2 A.C. 333 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 1 CLC 749 AWB Geneva SA v. North America Steamships Limited [2007] 2 Lloyd’s Rep 31 Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Cosmos Trading Corporation [2000] 1 BCLC 813 Banque Indosuez SA v. Ferromet Resources Inc [1993] BCLC 112 Bilta (UK) Ltd v Nazir (No 2) [2013] 2 WLR 825 Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2014] Ch 52 (CA) Bilta (UK) Ltd v. Nazir [2016] AC 1 (SC) Bloom v. Harms Offshore AHT “Taurus” GmbH & Co KG [2010] Ch 187 Case 17-2992, Document 1093-2, 05/09/2018, 2299206, Page2 of 111 Exhibit List Cases, continued Re Paramount Airways Ltd [1993] Ch 223 Picard v. Bernard L Madoff Investment Securities LLC BVIHCV140/2010 B Rubin v. Eurofinance SA [2013] 1 AC 236; [2012] UKSC 46 Singularis Holdings Ltd v. PricewaterhouseCoopers [2014] UKPC 36, [2015] A.C. 1675 Stichting Shell Pensioenfonds v. Krys [2015] AC 616; [2014] UKPC 41 Other Authorities McPherson’s Law of Company Liquidation (4th ed. 2017) Anthony Smellie, A Cayman Islands Perspective on Trans-Border Insolvencies and Bankruptcies: The Case for Judicial Co-Operation , 2 Beijing L. -

Cross-Border Insolvency of Enterprise Groups

Educational Materials Tuesday, September 29, 2015 | 3:00 PM – 4:30 PM NCBJ/ACB Joint International Program The Emerging Architecture for Coordinated Restructuring of International Corporate Groups Presented by: NCBJ/ACB Joint International Program: The Emerging Architecture for Coordinated Restructuring of International Corporate Groups Table of Contents Panel Summary….…………………………………………………………….…………………………………………………………..1 UNCITRAL’s Work in the Development of a Model Law on Group Enterprises by Christopher J. Redmond……………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 Discussion Under Mexican Corporate Law and the 2014 Insolvency Reforms of the Obligations of Officers and Directors in the Restructuring of Multi-National Groups by Agustin Berdeja-Prieto………………………………………………………………………………………………………………23 Summary of Key Amendments to Mexico’s Commercial Insolvency Law Effective 1-14-11…..………35 Developments in Cross-Border Avoidance and Recovery by Daniel M. Glosband…………………………..38 Regulation (EU) 2015/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Insolvency Proceedings……….……………………………………………………………………………………………………50 UNCITRAL Working Paper 124……………………………………………………………………………………………………….104 UNCITRAL Working Paper 128……………………………………………………………………………………………………….122 UNCITRAL Working Paper 129……………………………………………………………………………………………………….142 UNCITRAL Working Paper 130……………………………………………………………………………………………………….155 Contracting Out of Secondary Insolvency Proceedings: The Main Liquidator’s Undertaking in the Meaning of Article 18 in the Proposal to Amend the EU Insolvency Regulation