Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multilingual Practices in Late Medieval English Official Writing an Edition of Documents from the Beverley Town Cartulary

Delia Schipor Multilingual practices in late medieval English official writing An edition of documents from the Beverley Town Cartulary MA in Literacy Studies Spring 2013 FACULTY OF ARTS AND EDUCATION MASTER’S THESIS Programme of study: Master of Arts in Spring semester, 2013 Literacy Studies Open Author: Delia Schipor ………………………………………… (Author’s signature) Supervisor: Merja Stenroos Thesis title: Multilingual practices in late medieval English official writing An edition of documents from the Beverley Town Cartulary Keywords: Middle English, multilingualism, No. of pages: 100 cartulary, loanwords, code-switching + appendices/other: 52 Stavanger, 16 May 2013 date/year Acknowledgements ‘No man is an island, entire of itself...’ (John Donne, Devotions upon emergent occasions and seuerall steps in my sicknes - Meditation XVII, 1624) I am very content to be able to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Merja Stenroos for her excellent advice and patient guidance. The current work would not have been completed without her extensive efforts, extraordinary ability to motivate me and genuine interest in my work. I am also thankful to my extremely amiable teachers and colleagues at UiS for their help and suggestions. I would like to show my appreciation to Elizabeth Baker of the East Riding of Yorkshire Archives and Local Studies Service for consulting the original manuscript and confirming the similarity of the scribal hand through most of it. My parents have always encouraged me to study and actively supported all my academic endeavours. Thank you, I would not be here, physically and metaphorically, without your care and affection. I am grateful to all my friends, who have inspired and cheered me up. -

Saint Joan Timeline Compiled by Richard Rossi

1 Saint Joan Timeline Compiled by Richard Rossi A certain understanding of the historical background to Saint Joan is necessary to fully understand the various intricacies of the play. As an ocean of ink has been spilled by historians on Joan herself, I shall not delve too deeply into her history, keeping closely to what is relevant to the script. My dates, which may not necessarily match those that Shaw used, are the historically accepted dates; where there is discrepancy, I have notated. In some cases, I have also notated which characters refer to certain events in the timeline. There is a great deal of history attached to this script; the Hundred Years War was neither clean nor simple, and Joan was, as The Inquisitor says, “...crushed between these mighty forces, the Church and the Law.” 1st Century: Saint Peter founds the Catholic Church of Rome. (Warwick mentions St. Peter) 622: Establishment of Mohammad’s political and religious authority in Medina. (Cauchon mentions the prophet) 1215: The Waldensian movement, founded by Peter Waldo around 1170, is declared heretical at the Fourth Lateran Council. The movement had previously been declared heretical in 1184 at the Synod of Verona, and in 1211 80+ Waldensians were burned at the stake at Strausbourg. This was one of the earliest proto-Protestant groups and was very nearly destroyed. 1230’s: Establishment of the Papal Inquisition, which would later prosecute the trial against Joan of Arc. (Mentioned by Warwick. This is the same inquisition mentioned throughout the script) 1328: Charles IV of France dies without a male heir, ending the Capetian Dynasty and raising some very serious questions regarding the right of inheritance. -

Schützen Roman Besuchen Sie Uns Im Internet

Mac P. Lorne Der Herr der Bogen- schützen Roman Besuchen Sie uns im Internet: www.knaur.de Originalausgabe August 2017 Knaur Taschenbuch © 2017 Knaur Taschenbuch Ein Imprint der Verlagsgruppe Droemer Knaur GmbH & Co. KG, München Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk darf – auch teilweise – nur mit Genehmigung des Verlags wiedergegeben werden. Redaktion: Dr. Heike Fischer Umschlaggestaltung: ZERO Werbeagentur, München Umschlagabbildung: FinePic®, München / shutterstock Abbildung: ihorzigor / istock Karte: Computerkartographie Carrle Satz: Adobe InDesign im Verlag Druck und Bindung: CPI books GmbH, Leck ISBN 978-3-426-52082-6 2 4 5 3 1 Für Inga, die Liebe meines Lebens »Frieden ist ein Schatz, der nicht hoch genug gelobt werden kann. Ich hasse den Krieg. Er sollte niemals gerühmt werden!« Charles de Valois, Herzog von Orléans, der in seiner fünfundzwanzig Jahre währenden Gefangenschaft in England zu dieser Erkenntnis kam. Inhaltsverzeichnis Personenregister .................................. 13 1. Teil Von Pontefract nach Azincourt, 1400 –1415 ........... 17 2. Teil Von Domrémy nach Varennes, 1416 –1425 ............ 265 3. Teil Von London nach Rouen, 1425 –1431 ................. 449 Epilog .......................................... 685 Historische Anmerkungen ......................... 689 Zeittafel ......................................... 694 Glossar ......................................... 696 Bibliographie .................................... 702 9 Personenregister (historische Personen, die der Leser im Laufe der Handlung kennenlernen wird) Die Engländer John Holland – geb. 1395, gest. 1447, ab 1415 Earl of Hunting- don, ab 1439 II. Duke of Exeter, ein Mann, der ein Ziel hat John Holland – sein Vater, Earl of Huntingdon, I. Duke of Exeter, Anfang 1400 umgebracht Elizabeth of Lancaster – seine Mutter, Tochter des John of Gaunt, heiratet in zweiter Ehe John Cornwall John und Maud Lovel of Titchmarsh – seine Zieheltern Richard II. – König von England, 1399 abgesetzt und später umgebracht Henry Bolingbroke – als Henry IV. -

Saint Joan Script Glossary Compiled by Richard Rossi Italicized Definitions Have an Accompanying Picture Scene I

1 Saint Joan Script Glossary Compiled by Richard Rossi Italicized definitions have an accompanying picture Scene I Meuse River: During the time of the play, this roughly North/South river indicated the border between the Holy Roman Empire and the Kingdom of France. Approximately the red line, with Lorraine as the tan county at the bottom right, and Champagne on the left. Lorraine: The Duchy of Upper Lorraine, ruled by the dynasty of Gérard de Châtenois, was de facto independent from the 10th to 15th centuries. Intersected by the Meuse and Moselle rivers, it had a great deal of trade and information passing through, which made it an enticing target. In 1431, a mere two years after the start of Saint Joan, the Duchy was ceded to the House of Anjou, specifically René I, from whom it was incorporated into France in 1480. Champagne: Under the rule of the Counts of Champagne until 1284, the marriage of Philip the Fair and Joan I of Navarre brought it under the royal domain. During the High Middle Ages (1000-1300), the County of Champagne was one of the most powerful fiefs in France, home to the largest financial and commercial markets in Western Europe. 2 Vaucouleurs Castle: The main defense of “the town that armed Joan of Arc” and the residence of Robert de Baudricourt. The unruined structures, including the gothic chapel on the right, were rebuilt during the 18th century. Robert de Baudricourt: (1400-1454) minor French nobility, the son of the chamberlain of the Duke of Bar (Liebald de Baudricourt). -

La Hire Et Poton De Xaintrailles, Capitaines De Charles Vii Et Compagnons De Jeanne D’Arc

Camenulae 15, octobre 2016 Christophe FURON LA HIRE ET POTON DE XAINTRAILLES, CAPITAINES DE CHARLES VII ET COMPAGNONS DE JEANNE D’ARC « Inséparables »1, « compagnons de Jeanne »2 : telle est l’image que La Hire, moins connu sous le nom d’Étienne de Vignoles, et Jean, dit Poton, de Xaintrailles laissèrent à la postérité, jusque dans l’historiographie la plus récente. Invariablement, les historiens les présentent comme de rudes capitaines de compagnie gascons, toujours fidèles au dauphin puis roi Charles VII, dont le point d’orgue de leur carrière se situe au moment de l’épopée johannique, plus précisément lors du siège d’Orléans3. Pourtant, les historiens se sont peu intéressés à ces deux capitaines : la dernière publication consacrée à La Hire date de 19684 et, pour ce qui concerne Poton de Xaintrailles, il faut remonter à… 19025. C’est cette image, persistante dans l’historiographie française au point d’en devenir un lieu commun, qu’il convient donc d’interroger. Il ne s’agit pas de tenter de dissocier le mythe de l’Histoire mais plutôt de comprendre comment, au cours des siècles, l’un et l’autre se sont nourris au point de constituer aujourd’hui une sorte d’image d’Épinal de la guerre de Cent Ans et de l’histoire de Jeanne d’Arc. Pour cela, retracer les carrières respectives des deux capitaines permet de comprendre le rôle du roi dans leur ascension, d’évaluer la place et l’éventuelle incidence que l’épopée johannique a pu avoir sur celle-ci et de questionner la réalité de leur compagnonnage. -

The Wilted Lily Representations of the Greater Capetian Dynasty Within the Vernacular Tradition of Saint-Denis, 1274-1464

THE WILTED LILY REPRESENTATIONS OF THE GREATER CAPETIAN DYNASTY WITHIN THE VERNACULAR TRADITION OF SAINT-DENIS, 1274-1464 by Derek R. Whaley A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury, 2017. ABSTRACT Much has been written about representations of kingship and regnal au- thority in the French vernacular chronicles popularly known as Les grandes chroniques de France, first composed at the Benedictine abbey of Saint-Denis in 1274 by the monk Primat. However, historians have ignored the fact that Primat intended his work to be a miroir for the princes—a didactic guidebook from which cadets of the Capetian royal family of France could learn good governance and morality. This study intends to correct this oversight by analysing the ways in which the chroniclers Guillaume de Nangis, Richard Lescot, Pierre d’Orgemont, Jean Juvénal des Ursins, and Jean Chartier constructed moral character arcs for many of the members of the Capetian family in their continua- tions to Primat’s text. This thesis is organised into case studies that fol- low the storylines of various cadets from their introduction in the narrative to their departure. Each cadet is analysed in isolation to deter- mine how the continuators portrayed them and what moral themes their depictions supported, if any. Together, these cases prove that the chron- iclers carefully crafted their narratives to serve as miroirs, but also that their overarching goals shifted in response to the growing political cri- ses caused by the Hundred Years War (1337-1453) and the Armagnac- Burgundian civil war (1405-1435). -

Women and Power at the French Court, 1483-1563

GENDERING THE LATE MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN WORLD Broomhall (ed.) Women and Power at the French Court, 1483-1563 Court, French the at Power and Women Edited by Susan Broomhall Women and Power at the French Court, 1483-1563 Women and Power at the French Court, 1483–1563 Gendering the Late Medieval and Early Modern World Series editors: James Daybell (Chair), Victoria E. Burke, Svante Norrhem, and Merry Wiesner-Hanks This series provides a forum for studies that investigate women, gender, and/ or sexuality in the late medieval and early modern world. The editors invite proposals for book-length studies of an interdisciplinary nature, including, but not exclusively, from the fields of history, literature, art and architectural history, and visual and material culture. Consideration will be given to both monographs and collections of essays. Chronologically, we welcome studies that look at the period between 1400 and 1700, with a focus on any part of the world, as well as comparative and global works. We invite proposals including, but not limited to, the following broad themes: methodologies, theories and meanings of gender; gender, power and political culture; monarchs, courts and power; constructions of femininity and masculinity; gift-giving, diplomacy and the politics of exchange; gender and the politics of early modern archives; gender and architectural spaces (courts, salons, household); consumption and material culture; objects and gendered power; women’s writing; gendered patronage and power; gendered activities, behaviours, rituals and fashions. Women and Power at the French Court, 1483–1563 Edited by Susan Broomhall Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Ms-5116 réserve, fol. -

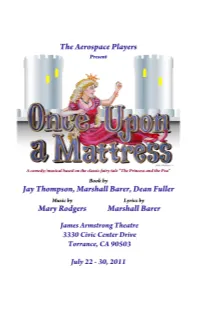

Mattress Program

Save the dates! The Aerospace Players tentatively announce our next three productions . Camelot February 3, 4, 5, 10, 11, 2012 Director: Chuck Gustafson Producer: JoMarie Rosser Bye Bye Birdie July 20, 21, 22, 27, 28, 2012 Director: John Woodcock Producers: Susan Tabak and Chuck Gustafson Fiddler on the Roof July 19, 20, 21, 26, 27, 2013 Director: Melissa Brandzel The Aerospace Players present Once Upon a Mattress ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ Concessions Snacks and cold beverages are available in the lobby at intermission 50/50 Drawing The winner receives 50% of the money collected at each performance. The winning number will be posted in the lobby prior to the end of each performance. Paul’s Photo Gift Certificates The winner at each show receives a $100 gift certificate for photography classes at Paul’s Photo. Improve your ability to capture treasured memories! Actor/Orchestra-Grams: $1 each “Wish them Luck for Only a Buck” All proceeds support The Aerospace Players production costs – Enjoy the Show! Director’s Note Welcome to the theater! Once Upon a Mattress is one of my all-time favorite shows in musical theater history. This production marks my 12th production of it, having performed as one of the first Prince Dauntlesses on tour when the show was first released back in the ’60s. I’ve played Dauntless five times and directed and choreographed the show six other times. When I was offered the chance to do the TAP production I was beyond excited. Now on to the challenge! Many classic shows should not be touched. Standards like most Rodgers and Hammerstein shows should be done as a classic. -

The Fall of English France 1449–53

THE FALL OF ENGLISH FRANCE 1449–53 DAVID NICOLLE ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN • 241 THE FALL OF ENGLISH FRANCE 1449–53 DAVID NICOLLE ILLUSTRATED BY GRAHAM TURNER Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN 5 CHRONOLOGY 8 OPPOSING FORCES 10 The reformed French army of Charles VII English armies in the mid-15th century Morale and the rise of nationalism OPPOSING COMMANDERS 17 French commanders English commanders THE FALL OF NORMANDY 22 The English invasion From the Grand-Vey to Formigny The battle of Formigny The final collapse in Normandy THE FALL OF GASCONY 42 The battle of Castillon The end of English Gascony AFTERMATH 84 The impact on France The impact on England Postscript in Calais THE BATTLEFIELDS TODAY 92 FURTHER READING 93 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com The decline of English France: frontiers c.1448 England and English-controlled territory at the start of 1449 Normandy and Gascony Irish principalities under varying degrees of English control Regions of southern Scotland under some degree of English control French royal territory at the start of 1449 Major French feudal domains, excluding Burgundian domains Burgundian territory within the Kingdom of France SCOTLAND Burgundian territory within the Empire Provençe ruled by a member of the French dynasty of Anjou Territory regained by the French crown and Duchy of Burgundy, 1428–44 Edinburgh Maine handed over to French control, March 1448 -

Dossier Pédagogique Du Château De Blandy-Les-Tours

Département de Seine-et-Marne Château de Blandy-les-Tours © 2015 Réalisation : Département de Seine-et-Marne Impression : Imprimerie Champagnac Crédit photo de couverture : © Département de Seine-et-Marne, Patrick Loison Nous avons le plaisir de vous offrir le dossier pédagogique du château de Blandy-les-Tours. Dans le volet gauche, des fiches informatives et pratiques vous aideront à construire votre sortie. Dans le volet droit, des fiches documentaires vous permettront de préparer vos élèves à la découverte du château. Le Département de Seine-et-Marne mène une véritable politique en faveur de l’action éducative. Différents guides et dossiers pédagogiques sont à votre disposition pour préparer vos visites. CHÂTEAU DE BLANDY-LES-TOURS - DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE DE BLANDY-LES-TOURS CHÂTEAU Nous espérons ainsi contribuer à développer chez vos élèves le plaisir d’apprendre, en découvrant le patrimoine culturel seine-et-marnais. Le château de Blandy-les-Tours est un des derniers témoins de l’architecture DÉPARTEMENT DE SEINE-ET-MARNE Dossier Bonne visite à tous. militaire médiévale conservés en Île-de-France. CHÂTEAU DE BLANDY-LES-TOURS Manoir fortifié édifié au XIIIe siècle par les vicomtes de Melun pour défendre 77115 BLANDY-LES-TOURS le domaine royal face à la frontière champenoise, il devient un véritable château 01 60 59 17 80 e pédagogique fort au XIV siècle pendant la guerre de Cent Ans. chateaublandylestours À l’issue du conflit, il perd ses fonctions militaires et devient purement résidentiel. @chateaublandy Transformé en ferme au XVIIIe siècle, il tombe en ruines. Aujourd’hui remarquablement restauré par le Département, le château de Blandy-les-Tours permet aux élèves de remonter huit siècles d’histoire, jusqu’au cœur du Moyen Âge. -

Royal and Magnate Bastards in the Later Middle Ages: the View from Scotland

ALEXANDER GRANT Royal and Magnate Bastards in the Later Middle Ages: The View from Scotland Theory and Practice in Scotland and Elsewhere Medieval Scotland’s law on bastardy is set out in the lawbook Regiam Majestatem (c.1320): ‘No bastard or other person not born in lawful wedlock can be an heir’; ‘a person begotten or born before his father subsequently marries his mother … cannot under any circum- stances be treated as an heir or allowed to claim the inheritance’; and ‘a bastard … can have no heir except the heir of his body born in wedlock’.1 Regiam was copying the English Tractatus de legibus et consuetudinibus regni Anglie (c.1185)2 – and of course both texts are stating the rules that became standard across most of Western Europe in the twelfth century, following both the tightening of marriage laws imposed by Gregorian Church Reform, and the ‘feudal’ shift in succession practice away from kin-groups towards primogeniture (including female inheritance). Before the new rules, bastards were not necessarily disadvantaged within their male kinship groups, any of whose senior members could become head of their kin; but after lay society’s ‘Gregorianization’ they were excluded from the inheritance networks of their paternal houses or domus, and also from those of their siblings and other collaterals. In a sense, bastards were made kinless – and indeed came to be regarded in theory as polluted offspring of corrupt stock, ‘a kind of monstros- ity’.3 But that was not absolute: ‘every rule scheme includes devices that allow the rules to be adapted to social circumstances’.4 There were two formal ways of transforming polluted illegitimate status into legitimacy: through the parents’ subsequent marriage (if they had been free to marry when the bastard was born), a canon law principle followed by many secular authorities; and through specific ad hominem decrees or letters issued by popes or secular rulers. -

Krewe De Jeanne D'arc Characters

Krewe de Jeanne d’Arc Characters Roles for Full Members Overview: Most krewe members portray unspecified people of 1400s France – a lady, a lord, a knight, a priest, a wool merchant, etc. These “townspeople” are grouped into 4 “battalions”: • Domrémy (Joan’s hometown – we encourage families with young children to go here) • Orléans (our namesake city and the city Joan liberated from siege in her first victory – we encourage people costumed as nobles and upper class to go here) • Lady’s Knights Auxiliary (male and female krewe members costumed as knights belong here) • Restoration (the people of France calling for Joan’s name to be restored – people from all walks of life testified at the re-trial to clear her name) Two more battalions are open for krewe members to join: • Voices of Joan (this battalion supports the St. Michael, St. Catherine and St. Margaret characters with 12-foot props). Krewe members in this section wear matching high church clergy costumes. • Flaming Heretics: portray a specific character from Joan’s trial or dress in medieval-masquerade style to represent flames. Some krewe members choose to portray specific individuals from Joan’s history. Those characters will be assigned to one of the above battalions OR one of the other battalions as appropriate for their characters. Representing a specific character is free; you can also choose to purchase official doubloons and/or playing cards of your character for $200. Domrémy Like many youngsters, Joan tended the sheep as a girl, and a show piece of this battalion will be a set of rolling lifesize wood and fleece sheep (with hidden pockets to carry throws inside).