Animating Desire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual

Holliday, Christopher. " Toying with Performance: Toy Story, Virtual Puppetry and Computer- Animated Film Acting." Toy Story: How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature. By Susan Smith, Noel Brown and Sam Summers. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 87–104. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501324949.ch-006>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 07:14 UTC. Copyright © Susan Smith, Sam Summers and Noel Brown 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 87 Chapter 6 T OYING WITH PERFORMANCE: TOY STORY , VIRTUAL PUPPETRY AND COMPUTER-A NIMATED FILM ACTING C h r i s t o p h e r H o l l i d a y In the early 1990s, during the emergence of the global fast food industry boom, the Walt Disney studio abruptly ended its successful alliance with restaurant chain McDonald’s – which, since 1982, had held the monopoly on Disney’s tie- in promotional merchandise – and instead announced a lucrative ten- fi lm licensing contract with rival outlet, Burger King. Under the terms of this agree- ment, the Florida- based restaurant would now hold exclusivity over Disney’s array of animated characters, and working alongside US toy manufacturers could license collectible toys as part of its meal packages based on characters from the studio’s animated features Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1991), Aladdin (Ron Clements and John Musker, 1992), Th e Lion King (Roger Allers and Rob Minkoff , 1994), Pocahontas (Mike Gabriel and Eric Goldberg, 1995) and Th e Hunchback of Notre Dame (Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, 1996).1 Produced by Pixar Animation Studio as its fi rst computer- animated feature fi lm but distributed by Disney, Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995) was likewise subject to this new commercial deal and made commensu- rate with Hollywood’s increasingly synergistic relationship with the fast food market. -

Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2017 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Kevin L. Ferguson CUNY Queens College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/205 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Digital Surrealism: Visualizing Walt Disney Animation Studios Abstract There are a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, but most of them only pursue traditional forms of scholarship by extracting a single variable from the audiovisual text that is already legible to scholars. Instead, cinema and media studies should pursue a mostly-ignored “digital-surrealism” that uses computer-based methods to transform film texts in radical ways not previously possible. This article describes one such method using the z-projection function of the scientific image analysis software ImageJ to sum film frames in order to create new composite images. Working with the fifty-four feature-length films from Walt Disney Animation Studios, I describe how this method allows for a unique understanding of a film corpus not otherwise available to cinema and media studies scholars. “Technique is the very being of all creation” — Roland Barthes “We dig up diamonds by the score, a thousand rubies, sometimes more, but we don't know what we dig them for” — The Seven Dwarfs There are quite a number of fruitful digital humanities approaches to cinema and media studies, which vary widely from aesthetic techniques of visualizing color and form in shots to data-driven metrics approaches analyzing editing patterns. -

Spatial Design Principles in Digital Animation

Copyright by Laura Beth Albright 2009 ABSTRACT The visual design phase in computer-animated film production includes all decisions that affect the visual look and emotional tone of the film. Within this domain is a set of choices that must be made by the designer which influence the viewer's perception of the film’s space, defined in this paper as “spatial design.” The concept of spatial design is particularly relevant in digital animation (also known as 3D or CG animation), as its production process relies on a virtual 3D environment during the generative phase but renders 2D images as a final product. Reference for spatial design decisions is found in principles of various visual arts disciplines, and this thesis seeks to organize and apply these principles specifically to digital animation production. This paper establishes a context for this study by first analyzing several short animated films that draw attention to spatial design principles by presenting the film space non-traditionally. A literature search of graphic design and cinematography principles yields a proposed toolbox of spatial design principles. Two short animated films are produced in which the story and style objectives of each film are examined, and a custom subset of tools is selected and applied based on those objectives. Finally, the use of these principles is evaluated within the context of the films produced. The two films produced have opposite stylistic objectives, and thus show two different viewpoints of applying the toolbox. Taken ii together, the two films demonstrate application and analysis of the toolbox principles, approached from opposing sides of the same system. -

A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2012 Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values Allyson Scott California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Scott, Allyson, "Almost there : a totally awesome study of animated Disney films and the development of American values" (2012). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 391. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/391 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social and Behavioral Sciences Department Senior Capstone California State University, Monterey Bay Almost There: A Totally Awesome Study of Animated Disney Films and the Development of American Values Dr. Rebecca Bales, Capstone Advisor Dr. Gerald Shenk, Capstone Instructor Allyson Scott Spring 2012 Acknowledgments This senior capstone has been a year of research, writing, and rewriting. I would first like to thank Dr. Gerald Shenk for agreeing that my topic could be more than an excuse to watch movies for homework. Dr. Rebecca Bales has been a source of guidance and reassurance since I declared myself an SBS major. Both have been instrumental to the completion of this project, and I truly appreciate their humor, support, and advice. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’S Pocahontas

Cyrus 1 Lydia A. Cyrus Dr. Squire ENG 440 Film Analysis Revision Fabricated History and False Feminism: Historical Inaccuracies and a False Sense of Feminism in Disney’s Pocahontas In 1995, following the hugely financial success of The Lion King, which earned Disney close to one billion is revenue, Walt Disney Studios was slated to release a slightly more experimental story (The Lion King). Previously, many of the feature- length films had been based on fairy tales and other fictional stories and characters. However, over a Thanksgiving dinner in 1990 director Mike Gabriel began thinking about the story of Pocahontas (Rebello 15). As the legend goes, Pocahontas was the daughter of a highly respected chief and saved the life of an English settler, John Smith, when her father sought out to kill him. Gabriel began setting to work to create the stage for Disney’s first film featuring historical events and names and hoped to create a strong female lead in Pocahontas. The film would be the thirty-third feature length film from the studio and the first to feature a woman of color in the lead. The project had a lot of pressure to be a financial success after the booming success of The Lion King but also had the added pressure from director Gabriel to get the story right (Rebello 15). The film centers on Pocahontas, the daughter of the powerful Indian chief, Powhatan. When settlers from the Virginia Company arrive their leader John Smith sees it as an adventure and soon he finds himself in the wild and comes across Pocahontas. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

A Greener Disney Cidalia Pina

Undergraduate Review Volume 9 Article 35 2013 A Greener Disney Cidalia Pina Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Pina, Cidalia (2013). A Greener Disney. Undergraduate Review, 9, 177-181. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol9/iss1/35 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2013 Cidalia Pina A Greener Disney CIDALIA PINA Cidalia Pina is a isney brings nature and environmental issues to the forefront with its Geography major non-confrontational approach to programming meant for children. This opportunity raises awareness and is relevant to growing with a minor in environmental concerns. However this awareness is just a cursory Earth Sciences with Dstart, there is an imbalance in their message and effort with that of their carbon an Environmental footprint. The important eco-messages that Disney presents are buried in fantasy and unrealistic plots. As an entertainment giant with the world held magically concentration. This essay was captive, Disney can do more, both in filmmaking and as a corporation, to facilitate completed as the final paper for Dr. a greener planet. James Bohn’s seminar course: The “Disney is a market driven company whose animated films have dealt with nature Walt Disney Company and Music. in a variety of ways, but often reflect contemporary concerns, representations, and Cidalia learned an invaluable amount shifting consciousness about the environment and nature.” - Wynn Yarbrough, about the writing and research University of the District of Columbia process from Dr. -

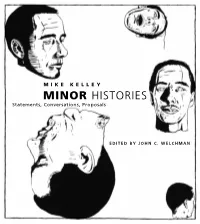

MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY Edited by John C

KELLEY MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY edited by John C. Welchman What John C. Welchman calls the “blazing network of focused conflations” from which Mike Kelley’s styles are generated is on display in all its diversity in this second volume of his writings. The first volume, Foul Perfection, contained thematic essays and writings about other artists; this collection concentrates on Kelley’s own work, ranging from texts in “voices” that grew out of scripts for performance pieces to expository critical and autobiographical writings. Minor Histories organizes Kelley’s writings into five sections. “Statements” consists of twenty pieces produced MINOR between 1984 and 2002 (most of which were written to accompany exhibitions), including “Ajax,” which draws on MIKE KELLEY Homeric epic, Colgate-Palmolive advertising, and Longinus to present its eponymous hero; “Some Aesthetic High Points,” an exercise in autobiography that counters the standard artist bio included in catalogs and press releases; and a sequence of “creative writings” that use mass cultural tropes in concert with high art mannerisms—approximating in prose the visu- MINOR HISTORIES al styles that characterize Kelley’s artwork. “Video Statements and Proposals” are introductions to videos made by Kelley and other artists, including Paul McCarthy and Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose. “Image-Texts” offers writings that accom- Statements, Conversations, Proposals pany or are part of artworks and installations. This section includes “A Stopgap Measure,” Kelley’s zestful millennial essay in social satire, and “Meet John Doe,” a collage of appropriated texts. The section “Architecture” features a discussion of Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995) and an interview in which he reflects on the role of architecture in his work. -

9781474410571 Contemporary

CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd i 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Traditions in American Cinema Series Editors Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer Titles in the series include: The ‘War on Terror’ and American Film: 9/11 Frames Per Second Terence McSweeney American Postfeminist Cinema: Women, Romance and Contemporary Culture Michele Schreiber In Secrecy’s Shadow: The OSS and CIA in Hollywood Cinema 1941–1979 Simon Willmetts Indie Reframed: Women’s Filmmaking and Contemporary American Independent Cinema Linda Badley, Claire Perkins and Michele Schreiber (eds) Vampires, Race and Transnational Hollywoods Dale Hudson Who’s in the Money? The Great Depression Musicals and Hollywood’s New Deal Harvey G. Cohen Engaging Dialogue: Cinematic Verbalism in American Independent Cinema Jennifer O’Meara Cold War Film Genres Homer B. Pettey (ed.) The Style of Sleaze: The American Exploitation Film, 1959–1977 Calum Waddell The Franchise Era: Managing Media in the Digital Economy James Fleury, Bryan Hikari Hartzheim, and Stephen Mamber (eds) The Stillness of Solitude: Romanticism and Contemporary American Independent Film Michelle Devereaux The Other Hollywood Renaissance Dominic Lennard, R. Barton Palmer and Murray Pomerance (eds) Contemporary Hollywood Animation: Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown www.edinburghuniversitypress.com/series/tiac 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM CONTEMPORARY HOLLYWOOD ANIMATION Style, Storytelling, Culture and Ideology Since the 1990s Noel Brown 66543_Brown.indd543_Brown.indd iiiiii 330/09/200/09/20 66:43:43 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance.