The Relation of the Schleswig-Holstein Question to the Unification of Germany: 1865-1866

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

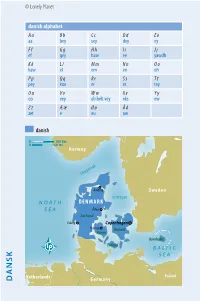

Danish Alphabet DENMARK Danish © Lonely Planet

© Lonely Planet danish alphabet A a B b C c D d E e aa bey sey dey ey F f G g H h I i J j ef gey haw ee yawdh K k L l M m N n O o kaw el em en oh P p Q q R r S s T t pey koo er es tey U u V v W w X x Y y oo vey do·belt vey eks ew Z z Æ æ Ø ø Å å zet e eu aw danish 0 100 km 0 60 mi Norway Skagerrak Aalborg Sweden Kattegat NORTH DENMARK SEA Århus Jutland Esberg Copenhagen Odense Zealand Funen Bornholm Lolland BALTIC SEA Poland Netherlands Germany DANSK DANSK DANISH dansk introduction What do the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and the existentialist philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard have in common (apart from pondering the complexities of life and human character)? Danish (dansk dansk), of course – the language of the oldest European monarchy. Danish contributed to the English of today as a result of the Vi- king conquests of the British Isles in the form of numerous personal and place names, as well as many basic words. As a member of the Scandinavian or North Germanic language family, Danish is closely related to Swedish and Norwegian. It’s particularly close to one of the two official written forms of Norwegian, Bokmål – Danish was the ruling language in Norway between the 15th and 19th centuries, and was the base of this modern Norwegian literary language. In pronunciation, however, Danish differs considerably from both of its neighbours thanks to its softened consonants and often ‘swallowed’ sounds. -

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: a GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK for STEM CELLS in BONE HEALING

Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein BONEBANK: A GERMAN- DANISH BIOBANK FOR STEM CELLS IN BONE HEALING ScanBalt Forum, Tallin, October 2017 PROJECT IN A NUTSHELL Start: 1th September 2015 End: 29 th February 2019 Duration: 36 months Total project budget: 2.377.265 EUR, 1.338.876 EUR of which are Interreg funding 3 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 PROJECT STRUCTURE Project Partners University Medical Centre Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck (Lead Partner) Odense University Hospital Stryker Trauma Soventec Life Science Nord Network partners Syddansk Sundhedsinnovation WelfareTech Project Management DSN – Connecting Knowledge 4 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 OPPORTUNITIES, AMBITION AND GOALS • Research on stem cells is driving regenerative medicine • Availability of high-quality bone marrow stem cells for patients and research is limited today • Innovative approach to harvest bone marrow stem cells during routine operations for fracture treatment • Facilitating access to bone marrow stem cells and driving research and innovation in Germany- Denmark Harvesting of bone marrow stem cells during routine operations in the university hospitals Odense and Lübeck Cross-border biobank for bone marrow stem cells located in Odense and Lübeck Organisational and exploitation model for the Danish-German biobank providing access to bone marrow stem cells for donators, patients, public research and companies 5 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. Oktober 2017 ACHIEVEMENTS SO FAR Harvesting of 53 samples, both in Denmark and Germany Donors/Patients Most patients (34) are over 60 years old 19 women 17 women Germany Isolation of stem cells possible Denmark 7 men 10 men Characterization profiles of stem cells vary from individual to individual Age < 60 years > 60 years 27 7 9 10 women men 6 BONEBANK: A German-Danish biobank for stem cells in bone healing 20. -

Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea Population of the Common Eider Somateria M

Baltic/Wadden Sea Common Eider 167 Status of the Baltic/Wadden Sea population of the Common Eider Somateria m. mollissima M. Desholm1, T.K. Christensen1, G. Scheiffarth2, M. Hario3, Å. Andersson4, B. Ens5, C.J. Camphuysen6, L. Nilsson7, C.M. Waltho8, S-H. Lorentsen9, A. Kuresoo10, R.K.H. Kats5,11, D.M. Fleet12 & A.D. Fox1 1Department of Coastal Zone Ecology, National Environmental Research Institute, Grenåvej 12, 8410 Rønde, Denmark. Email: [email protected]/[email protected]/[email protected] 2Institut für Vogelforschung, ‘Vogelwarte Helgoland’, An der Vogelwarte 21, D - 26386 Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Email: [email protected] 3Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Söderskär Game Research Station. P.O.Box 6, FIN-00721 Helsinki, Finland. Email: [email protected] 4Ringgatan 39 C, S-752 17 Uppsala, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 5Alterra, P.O. Box 167, 1790 AD Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email:[email protected]/[email protected] 6Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (Royal NIOZ), P.O. Box 59, 1790 AB Den Burg, Texel, The Netherlands. Email: [email protected] 7Department of Animal Ecology, University of Lund, Ecology Building, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden. Email: [email protected] 873 Stewart Street, Carluke, Lanarkshire, Scotland, UK, ML8 5BY. Email: [email protected] 9Norwegian Institute for Nature Research. Tungasletta 2, N-7485 Trondheim, Norway Email: [email protected] 10Institute of Zoology and Botany, Riia St. 181, 51014, Tartu, Estonia. Email: [email protected] 11Department of Animal Ecology, University of Groningen, Kerklaan 30, 9751 NH, Groningen, The Netherlands. -

German Historical Institute London Bulletin

German Historical Institute London Bulletin Bd. 25 2003 Nr. 2 Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Stiftung Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. BOOK REVIEWS FRIEDRICH EDELMAYER, Söldner und Pensionäre: Das Netzwerk Philipps II. im Heiligen Römischen Reich, Studien zur Geschichte und Kultur der Iberischen und Iberoamerikanischen Länder, 7 (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2002) ISBN 3 486 56672 5; (Vienna: Verlag für Ge- schichte und Politik, 2002) ISBN 3 7028 0394 7. 318 pp. EURO 44.80 Not many monographs have been written about the relations be- tween Philip II or the Spanish monarchy and the Holy Roman Empire between about 1560 and 1580. The cleverly stage-managed abdication of Philip’s father, Charles V, as Holy Roman Emperor, and the accession to this throne of his Austrian brother, King of the Romans Ferdinand I, seemingly put an end to the chapter of German–Spanish union in the sixteenth century. Ferdinand now had to concentrate even more on the political consequences of the Re- formation in central Europe, while Philip turned to the daring exploits of the Spanish crown in Europe and abroad—in the increas- ingly confident Netherlands; in Hispanic America; in the Philippines, named after him in 1543, where he reformed the government around 1570; and in Portugal, which he was also able to unify politically with Spain in 1581 as a result of his first marriage, to Maria of Portugal. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

CEMENT for BUILDING with AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Portland Aalborg Cover Photo: the Great Belt Bridge, Denmark

CEMENT FOR BUILDING WITH AMBITION Aalborg Portland A/S Cover photo: The Great Belt Bridge, Denmark. AALBORG Aalborg Portland Holding is owned by the Cementir Group, an inter- national supplier of cement and concrete. The Cementir Group’s PORTLAND head office is placed in Rome and the Group is listed on the Italian ONE OF THE LARGEST Stock Exchange in Milan. CEMENT PRODUCERS IN Cementir's global organization is THE NORDIC REGION divided into geographical regions, and Aalborg Portland A/S is included in the Nordic & Baltic region covering Aalborg Portland A/S has been a central pillar of the Northern Europe. business community in Denmark – and particularly North Jutland – for more than 125 years, with www.cementirholding.it major importance for employment, exports and development of industrial knowhow. Aalborg Portland is one of the largest producers of grey cement in the Nordic region and the world’s leading manufacturer of white cement. The company is at the forefront of energy-efficient production of high-quality cement at the plant in Aalborg. In addition to the factory in Aalborg, Aalborg Portland includes five sales subsidiaries in Iceland, Poland, France, Belgium and Russia. Aalborg Portland is part of Aalborg Portland Holding, which is the parent company of a number of cement and concrete companies in i.a. the Nordic countries, Belgium, USA, Turkey, Egypt, Malaysia and China. Additionally, the Group has acti vities within extraction and sales of aggregates (granite and gravel) and recycling of waste products. Read more on www.aalborgportlandholding.com, www.aalborgportland.dk and www.aalborgwhite.com. Data in this brochure is based on figures from 2017, unless otherwise stated. -

Evidence from Hamburg's Import Trade, Eightee

Economic History Working Papers No: 266/2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 266 – AUGUST 2017 Great divergence, consumer revolution and the reorganization of textile markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s import trade, eighteenth century Ulrich Pfister Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Email: [email protected] Abstract The study combines information on some 180,000 import declarations for 36 years in 1733–1798 with published prices for forty-odd commodities to produce aggregate and commodity specific estimates of import quantities in Hamburg’s overseas trade. In order to explain the trajectory of imports of specific commodities estimates of simple import demand functions are carried out. Since Hamburg constituted the principal German sea port already at that time, information on its imports can be used to derive tentative statements on the aggregate evolution of Germany’s foreign trade. The main results are as follows: Import quantities grew at an average rate of at least 0.7 per cent between 1736 and 1794, which is a bit faster than the increase of population and GDP, implying an increase in openness. Relative import prices did not fall, which suggests that innovations in transport technology and improvement of business practices played no role in overseas trade growth. -

The Franco-Prussian War: Its Impact on France and Germany, 1870-1914

The Franco-Prussian War: Its Impact on France and Germany, 1870-1914 Emily Murray Professor Goldberg History Honors Thesis April 11, 2016 1 Historian Niall Ferguson introduced his seminal work on the twentieth century by posing the question “Megalomaniacs may order men to invade Russia, but why do the men obey?”1 He then sought to answer this question over the course of the text. Unfortunately, his analysis focused on too late a period. In reality, the cultural and political conditions that fostered unparalleled levels of bloodshed in the twentieth century began before 1900. The 1870 Franco- Prussian War and the years that surrounded it were the more pertinent catalyst. This event initiated the environment and experiences that catapulted Europe into the previously unimaginable events of the twentieth century. Individuals obey orders, despite the dictates of reason or personal well-being, because personal experiences unite them into a group of unconscious or emotionally motivated actors. The Franco-Prussian War is an example of how places, events, and sentiments can create a unique sense of collective identity that drives seemingly irrational behavior. It happened in both France and Germany. These identities would become the cultural and political foundations that changed the world in the tumultuous twentieth century. The political and cultural development of Europe is complex and highly interconnected, making helpful insights into specific events difficult. It is hard to distinguish where one era of history begins or ends. It is a challenge to separate the inherently complicated systems of national and ethnic identities defined by blood, borders, and collective experience. -

Wars Between the Danes and Germans, for the Possession Of

DD 491 •S68 K7 Copy 1 WARS BETWKEX THE DANES AND GERMANS. »OR TllR POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. BV t>K()F. ADOLPHUS L. KOEPPEN FROM THE "AMERICAN REVIEW" FOR NOVEMBER, U48. — ; WAKS BETWEEN THE DANES AND GERMANS, ^^^^ ' Ay o FOR THE POSSESSION OF SCHLESWIG. > XV / PART FIRST. li>t^^/ On feint d'ignorer que le Slesvig est une ancienne partie integTante de la Monarchie Danoise dont I'union indissoluble avec la couronne de Danemarc est consacree par les garanties solennelles des grandes Puissances de I'Eui'ope, et ou la langue et la nationalite Danoises existent depuis les temps les et entier, J)lus recules. On voudrait se cacher a soi-meme au monde qu'une grande partie de la popu- ation du Slesvig reste attacliee, avec une fidelite incbranlable, aux liens fondamentaux unissant le pays avec le Danemarc, et que cette population a constamment proteste de la maniere la plus ener- gique centre une incorporation dans la confederation Germanique, incorporation qu'on pretend medier moyennant une armee de ciuquante mille hommes ! Semi-official article. The political question with regard to the ic nation blind to the evidences of history, relations of the duchies of Schleswig and faith, and justice. Holstein to the kingdom of Denmark,which The Dano-Germanic contest is still at the present time has excited so great a going on : Denmark cannot yield ; she has movement in the North, and called the already lost so much that she cannot submit Scandinavian nations to arms in self-defence to any more losses for the future. The issue against Germanic aggression, is not one of a of this contest is of vital importance to her recent date. -

The Virtues of a Good Historian in Early Imperial Germany: Georg Waitz’S Contested Example 1

Published in Modern Intellectual History 15 (2018), 681-709. © Cambridge University Press. Online at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479244317000142 The Virtues of a Good Historian in Early Imperial Germany: Georg Waitz’s Contested Example 1 Herman Paul Recent literature on the moral economy of nineteenth-century German historiography shares with older scholarship on Leopold von Ranke’s methodological revolution a tendency to refer to “the” historical discipline in the third person singular. This would make sense as long as historians occupied a common professional space and/or shared a basic understanding of what it meant to be an historian. Yet, as this article demonstrates, in a world sharply divided over political and religious issues, historians found it difficult to agree on what it meant to be a good historian. Drawing on the case of Ranke’s influential pupil Georg Waitz, whose death in 1886 occasioned a debate on the relative merits of the example that Waitz had embodied, this article argues that historians in early Imperial Germany were considerably more divided over what they called “the virtues of the historian” than has been acknowledged to date. Their most important frame of reference was not a shared discipline but rather a variety of approaches corresponding to a diversity of models or examples (“scholarly personae” in modern academic parlance), the defining features of which were often starkly contrasted. Although common ground beneath these disagreements was not entirely absent, the habit of late nineteenth-century German historians to position themselves between Waitz and Heinrich von Sybel, Ranke and Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann, or other pairs of proper names turned into models of virtue, suggests that these historians experienced their professional environment as characterized primarily by disagreement over the marks of a good historian. -

France and the German Question, 1945–1955

CreswellFrance and and the Trachtenberg German Question France and the German Question, 1945–1955 ✣ What role did France play in the Cold War, and how is French policy in that conºict to be understood? For many years the prevailing as- sumption among scholars was that French policy was not very important. France, as the historian John Young points out, was “usually mentioned in Cold War histories only as an aside.” When the country was discussed at all, he notes, it was “often treated as a weak and vacillating power, obsessed with outdated ideas of a German ‘menace.’”1 And indeed scholars often explicitly argued (to quote one typical passage) that during the early Cold War period “the major obsession of French policy was defense against the German threat.” “French awareness of the Russian threat,” on the other hand, was sup- posedly “belated and reluctant.”2 The French government, it was said, was not eager in the immediate postwar period to see a Western bloc come into being to balance Soviet power in Europe; the hope instead was that France could serve as a kind of bridge between East and West.3 The basic French aim, according to this interpretation, was to keep Germany down by preserving the wartime alliance intact. Germany itself would no longer be a centralized state; the territory on the left bank of the Rhine would not even be part of Germany; the Ruhr basin, Germany’s industrial heartland, would be subject to allied control. Those goals, it was commonly assumed, were taken seriously, not just by General Charles de Gaulle, who headed the French provisional government until Jan- uary 1946, but by Georges Bidault, who served as foreign minister almost without in- terruption from 1944 through mid-1948 and was the most important ªgure in French foreign policy in the immediate post–de Gaulle period. -

60 Years German Basic Law: the German Constitution and Its Court

60 Years German Basic Law: The German Constitution and its Court Landmark Decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany in the Area of Fundamental Rights Jürgen Bröhmer, Clauspeter Hill & Marc Spitzkatz (Eds.) 2nd Edition Edited by Suhainah Wahiduddin LLB Hons (Anglia) Published by The Malaysian Current Law Journal Sdn Bhd E1-2, Jalan Selaman 1/2, Dataran Palma, 68000 Ampang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia [Co No 51143 M] Tel: 603-42705400 Fax: 603-42705401 2012 © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Berlin / Germany. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any material form or by any means, including photocopying and recording, or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication, without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addressed to the publisher. Such written permission must also be obtained before any part of this publication is stored in a retrieval system of any nature. The following parts have been published earlier under the copyright of: © Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, Baden-Baden / Germany Cases no. IV. 2 a) School Prayer, IV. 2 b) Classroom Crucifix, V. 2 d) First Broadcasting Decision and XV. a) and b) Solange I and II. Published in: Decisions of the Bundesverfassungsgericht - Federal Constitutional Court - Federal Republic of Germany, Vol. 1, 2 and 4, Baden-Baden 1993-2007. © Donald P. Kommers Case no. II. 1 a) Elfes, published in: Donald P. Kommers, The Constitutional of the Federal Republic of Germany, 2nd ed.