The Age of Decadence - the New York Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cave Without a Name June 6, 2020 at 7:30 PM

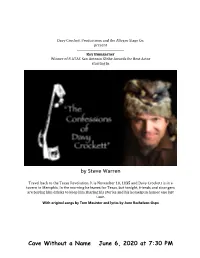

Davy Crockett Productions and the Allegro Stage Co. present Roy Bumgarner Winner of 8 ATAC San Antonio Globe Awards for Best Actor starring in by Steve Warren Travel back to the Texas Revolution. It is November 10, 1835 and Davy Crockett is in a tavern in Memphis. In the morning he leaves for Texas, but tonight, friends and strangers are buying him drinks to keep him sharing his stories and his homespun humor one last time. With original songs by Tom Masinter and lyrics by June Rachelson-Ospa Cave Without a Name June 6, 2020 at 7:30 PM Roy Bumgarner (Davy Crockett) Roy is one of San Antonio’s favorite and most versatile lead actors. He has performed on nearly every theater stage in town, including The Majestic Theatre with San Antonio Symphony. He is loved for his roles in Jane Eyre (Rochester), Annie (Daddy Warbucks), Sweeny Todd (Sweeney), The King & I (King), My Fair Lady (Higgins), Evita (Che), Camelot (Arthur), West Side Story (Tony), Titantic (Andrews), Lend Me a Tenor (Max), Chicago (Billy), Into the Woods (Wolf, Cinderella’s Prince), Jekyll & Hyde (Jekyll/Hyde), The Crucible (John Proctor), Noises Off (Gary), Urinetown (Officer Lockston), Visiting Mr. Green (Ross), The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Jasper), Taming of the Shrew (Petrucchio), The Lion in Winter (Richard), State Fair (Pat Gilbert), The Pajama Game (Sid), Godspell (Jesus), Crazy For You, Some Like it Hot, Forever Plaid, Vexed, Forbidden Broadway and more. He has created lead rosles in the following original musicals: Gone to Texas (Bowie), Fire on the Bayou (Eduardo), Roads Courageous (Brinkley), and High Hair & Jalapenos. -

100 Years of Barzun by Donors Kraft and Campbell

OPEN WIDE KARA WALKER SIEMENS Columbia Expands On Exhibit at SCIENCE DAY its Dental Plan | 5 The Whitney| 2 for Budding Scientists | 6 VOL. 33, NO. 04 NEWS AND IDEAS FOR THE COLUMBIA COMMUNITY OCTOBER 25, 2007 Athletic Goal: Climate Scientists Work To Battle $100 Million Disease By Bridget O’Brian By Clare Oh olumbia launched its $100 mil- lion campaign to transform the he International Research CUniversity’s athletics program, Institute for Climate and and in recognition of a $5 million Society (IRI), housed at gift, the playing field at Lawrence T Columbia’s Lamont campus A. Wien Stadium was named the in Palisades, New York, is Robert K. Kraft Field. Kraft is a 1963 graduate of Columbia College working with policy makers who now owns the New England in the nation of Colombia to Patriots. The field was renamed show how climate forecasts during homecoming weekend. can help communities better In addition to that gift, William prepare for climate-sensitive C. Campbell, chairman of the Uni- disease outbreaks. versity’s board of trustees and him- IRI scientists work around self a former captain and head coach the world to expand the knowl- of Lions football, pledged more than edge of climate and its rela- $10 million to the athletics initia- tionship to health, agriculture, tive. There were eight other gifts of water, and other sectors, $1 million or more. The Columbia Campaign for and help communities better Athletics: Achieving Excellence, adapt to changes that affect part of the University’s $4 billion their lives and livelihoods. capital campaign, has raised $46 Over the past three de- million so far. -

Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 10:30 AM - 11:50 AM Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age Dominique Pen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Pen, Dominique, "Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age" (2016). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 3. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/002/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Pen1 Prospero’s Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age Dominique Pen M.A. Candidate, Art History, School of Art 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Conference Pen2 In 2005, Yinka Shonibare was offered the prestigious distinction of becoming recognized as a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). As an artist whose work is characterized by his direct engagement with and critiques of power, the establishment, colonialism and imperialism, in many cases specifically relating to Britain’s past and present, some questioned whether he was going to refuse the honor. This inquiry was perhaps encouraged -

1 Introduction the Empire at the End of Decadence the Social, Scientific

1 Introduction The Empire at the End of Decadence The social, scientific and industrial revolutions of the later nineteenth century brought with them a ferment of new artistic visions. An emphasis on scientific determinism and the depiction of reality led to the aesthetic movement known as Naturalism, which allowed the human condition to be presented in detached, objective terms, often with a minimum of moral judgment. This in turn was counterbalanced by more metaphorical modes of expression such as Symbolism, Decadence, and Aestheticism, which flourished in both literature and the visual arts, and tended to exalt subjective individual experience at the expense of straightforward depictions of nature and reality. Dismay at the fast pace of social and technological innovation led many adherents of these less realistic movements to reject faith in the new beginnings proclaimed by the voices of progress, and instead focus in an almost perverse way on the imagery of degeneration, artificiality, and ruin. By the 1890s, the provocative, anti-traditionalist attitudes of those writers and artists who had come to be called Decadents, combined with their often bizarre personal habits, had inspired the name for an age that was fascinated by the contemplation of both sumptuousness and demise: the fin de siècle. These artistic and social visions of degeneration and death derived from a variety of inspirations. The pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), who had envisioned human existence as a miserable round of unsatisfied needs and desires that might only be alleviated by the contemplation of works of art or the annihilation of the self, contributed much to fin-de-siècle consciousness.1 Another significant influence may be found in the numerous writers and artists whose works served to link the themes and imagery of Romanticism 2 with those of Symbolism and the fin-de-siècle evocations of Decadence, such as William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Eugène Delacroix, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert. -

WASHINGTON, B.C. March 27, 1973. Jacques Barzun, Prominent

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JACQUES BARZUN TO DELIVER 1973 MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS WASHINGTON, B.C. March 27, 1973. Jacques Barzun, prominent educator, author and cultural historian, will deliver the 22nd annual Andrew W, Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art beginning Sunday April 1. The title of Professor Barzun's Mellon Lectures is The Use and Abuse of Art, with subtitles in the six-part series ranging from "Why Art Must Be Challenged" and "The Rise of Art as Religion" to "Art and Its Tempter, Science" and "Art in the Vacuum of Belief." The other titles are "Art the Destroyer" and "Art the Redeemer." The lectures will be given on six consecutive Sundays at 4:00 p.m. from April 1 through May 6 in the National Gallery Auditorium. The series is open to the public without charge. Professor Barzun 1 s publications include The French Race, Romanticism and the Modern Ego, Darwin, Marx, Wagner, and Berlioz and His Century. Among his critical works are Teacher in America, The House of Intellect, and The American University: How It Runs, Where It is Going. A native of France, Professor Barzun received his B.A 0 degree from Columbia College in New York in 1927 and began to teach there the same year. He also received his M.A. (1928) and Ph.D. (1932) from Columbia, where he became a full professor in 1945, (more) JACQUES BARZUN TO DELIVER 1973 MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS -2 specializing in comtemporary cultural history. -

The Jacques Barzun Award Lecture

PERNICIOUS AMNESIA: COMBATING THE EPIDEMIC Response to the Conferral of the Inaugural Jacques Barzun Award The American Academy for Liberal Education Washington, D.C. 8 November 1997 Jaroslav Pelikan Sterling Professor Emeritus Yale University The Jacques Barzun Award for Outstanding Contributions to Liberal Education The American Academy for Liberal Education is proud to establish the Jacques Barzun Award, honoring outstanding contributions to liberal education. Named in honor of one of the Academy’s founders, and its honorary chairman, Jacques Barzun, the award recognizes and celebrates qualities of scholarship and leadership in liberal education so perfectly embodied by Dr. Barzun himself. A distinguished scholar, teacher, author, and university administrator (he served for twelve years as Dean of Faculties and Provost of Columbia University), Jacques Barzun is internationally known as one of our most thoughtful commentators on the cultural history of the modern period. Among his most recent books are Critical Questions (a collection of his essays from 1940-1980), A Stroll With William James, and A Word or Two Before You Go. He has reflected on contemporary education in Begin Here: The Forgotten Conditions of Teaching and Learning, Teacher in America, and The American University, How it Runs, Where it is Going. Even a full recounting of Jacques Barzun’s forty or so books and translations, or of his many honors (he is a member of the American Philosophical Society, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts) would fail to do full justice to the extent of Barzun’s influence on liberal education in this country. -

De Sade's Theatrical Passions

06.puchner 4/19/05 2:28 PM Page 111 Martin Puchner Sade’s Theatrical Passions The Theater of the Revolution The Marquis de Sade entered theater history in 1964 when the Royal Shakespeare Company, under the direction of Peter Brook, presented a play by the unknown author Peter Weiss entitled, The Persecution and Assassination of Jean-Paul Marat as Performed by the Inmates of the Asylum of Charenton Under the Direction of the Marquis de Sade.1 Marat/Sade, as the play is usually called, became an extraordinary success story.2 By com- bining narrators with techniques developed in a multi-year workshop entitled “Theater of Cruelty,” Marat/Sade managed to link the two modernist visionaries of the theater whom everybody had considered to be irreconcilable opposites: Bertolt Brecht and Antonin Artaud. Marat/Sade not only fabricated a new revolutionary theater from the vestiges of modernism, it also coincided with a philosophical and cul- tural revision of the French revolution that had begun with Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s The Dialectics of Enlightenment (1944/69) and found a preliminary culmination in Michel Foucault’s History of Madness (1972). At the same time, the revival of Sade was fu- eled by the first complete publication of his work in French (1967) and by Roland Barthes’ landmark study, Sade Fourier Loyola (1971).3 Marat/Sade had thus hit a theatrical and intellectual nerve. Sade, however, belongs to theater history as more than just a char- acter in a play.Little is known about the historical Sade’s life-long pas- sion for the theater, about his work as a theater builder and manager, an actor and director. -

Utopian Aspirations in Fascist Ideology: English and French Literary Perspectives 1914-1945

Utopian Aspirations in Fascist Ideology: English and French Literary Perspectives 1914-1945 Ashley James Thomas Discipline of History School of History & Politics University of Adelaide Thesis presented as the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide March 2010 CONTENTS Abstract iii Declaration iv Acknowledgments v Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Interpreting Fascism: An Evolving 26 Historiography Chapter Three: The Fascist Critique of the Modern 86 World Chapter Four: Race, Reds and Revolution: Specific 156 Issues in the Fascist Utopia Chapter Five: Conclusion 202 Bibliography 207 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that utopian aspirations are a fruitful way to understand fascism and examines the utopian ideals held by a number of fascist writers. The intention of this thesis is not to define fascism. Rather, it is to suggest that looking at fascism’s goals and aspirations might reveal under-examined elements of fascism. This thesis shows that a useful way to analyse the ideology of fascism is through an examination of its ideals and goals, and by considering the nature of a hypothetical fascist utopia. The most common ways of examining fascism and attempting to isolate its core ideological features have been by considering it culturally, looking at the metaphysical and philosophical claims fascists made about themselves, or by studying fascist regimes, looking at the external features of fascist movements, parties and governments. In existing studies there is an unspoken middle ground, where fascism could be examined by considering practical issues in the abstract and by postulating what a fascist utopia would be like. -

THE FRENCH PHILOSOPHES and THEIR ENLIGHTENING MEDIEVAL PAST by John Frederick Logan

THE FRENCH PHILOSOPHES AND THEIR ENLIGHTENING MEDIEVAL PAST by John Frederick Logan The Enlightenment's scorn for the Middle Ages is well known. "Centuries of ignorance," "barbarous times," "miserable age"-such descriptions of medie- val life and culture seem to justify the assumption that a contempt for the Middle Ages was a uniform and central characteristic of the French Enlight- enment. B. A. Brou, for example, sees the medieval period as an epitome of everything despised by the philosophes: the men of the Enlightenment, he asserted, "rejected authority, tradition, and the past. Thus there was disdain for the Middle Ages."' Summarizing the philosophes' view of the medieval period, the French critic Edmond EstBve similarly declared that Bayle . .scarcely knew the M~ddleAges and did not like them. HISdisciples and successors knew this period no better and detested ~t even more. The historians spoke of it because, nonetheless, one could not cross out five or six centuries of our past-whatever distaste one might have. But they affected reluctance in all sorts of ways before approaching the subjecL2 Such interpretations of the attitude towards medieval history prevalent among the philosophes are quite understandable: the colorful, often-quot- ed comments of Voltaire on the decadence and ignorance of the past come immediately to mind. Furthermore, the task of the modern interpreter of Enlightenment historiography becomes much lighter if he can neatly and quickly dispense with the philosophes' view of the Middle Ages; a uniformly negative attitude toward the medieval period provides a most useful contrast to the sympathetic approach of many nineteenth century historians. -

Download File

A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Matthew Bridge All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT A Monster for Our Times: Reading Sade across the Centuries Matthew Bridge This doctoral dissertation looks at several readings and interpretations of the works of the Marquis de Sade, from the eighteenth century to the present. Ever since he was imprisoned under the Old Regime following highly publicized instances of physical and sexual abuse, Sade has remained a controversial figure who has been both condemned as a dangerous criminal and celebrated as an icon for artistic freedom. The most enduring aspect of his legacy has been a vast collection of obscene publications, characterized by detailed descriptions of sexual torture and murder, along with philosophical diatribes that offer theoretical justifications for the atrocities. Not surprisingly, Sade’s works have been subject to censorship almost from the beginning, leading to the author’s imprisonment under Napoleon and to the eventual trials of his mid-twentieth-century publishers in France and Japan. The following pages examine the reception of Sade’s works in relation to the legal concept of obscenity, which provides a consistent framework for textual interpretation from the 1790s to the present. I begin with a prelude discussing the 1956 trial of Jean-Jacques Pauvert, in order to situate the remainder of the dissertation within the context of how readers approached a body of work as quintessentially obscene as that of Sade. -

“The Queen of Decadence”: Rachilde and Sado

‘“The Queen of Decadence”: Rachilde and Sado-Masochistic Feminism’ Author[s]: Rebekkah Dilts Source: Moveable Type, Vol.11, ‘Decadence’ (2019) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.095 Moveable Type is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2019 Rebekkah Dilts. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. 10 Moveable Type 11 (2019) In 1884, the novel Monsieur Vénus took the French literary world by storm, and inaugurated its controversial female author, Rachilde, the ‘queen of decadence.’ Many critics did not believe that a young, aristocratic woman could possibly have devised such a salacious story. A literary press which specialized in erotica first published the book, but it was banned regardless, and Rachilde was even condemned to prison for pornographic writing. Subsequent editions therefore required fake male co-authors and introductions by famous male writers that consigned the novel not literature at all, but the case study of a hysterical woman. Rachilde also publicly denounced the feminism of her moment, a proclamation that affected the twentieth- century reception of her writing. Yet, following new French and English editions published in 2004, Monsieur Vénus has been hailed a queer forerunner in contemporary academic circles, even while questions about Rachilde’s feminist affiliations persist. This paper goes beyond the biographical details that have dominated conversation about Rachilde’s writing to closely interrogate the use of sexual violence in Monsieur Vénus, and in her much lesser-known novel, La Marquise de Sade (1887). -

The Sodomitic Reputation of Weimar Berlin Gregory Woods

9 The Sodomitic Reputation of Weimar Berlin Gregory Woods Resumo A Berlim da Republica de Weimar tornou-se a cidade europeia, por exceli!ncia, dos sonhos eroticos e dos pesadelos morais. Berlim tornou Sf 0 simbolo tanto das coisas maravilhosas que poderiam ser alcanr;adas se se lutasse por eias, quanta das coisas terriveis que poderiam aeonteeer se nao se lutasse contra elas. A proliferar;ao e a visibilidade da vida homossexual berlinense era tanto uma promessa quanto uma amear;a. 0 legado de Weimar nao foi tanto 0 moralismo vingativo do Nazismo, quanto 0 fervor eficaz com 0 qual a BerUm queer conseguiu se reestabelecer e prosperar depois da guerra, apesar de estar no iwsW epicentro da Guerra Fria. Palavras-chave: Berlim. Homossexualismo. Nazismo. Gragoata Niter6i, n. 14, p. 9- 27,1. sem. 2003 10 Visiting Berlin in 1919 in the aftermath of Germany's defeat in the Great War, Kurt von Stutterheim fOlmd that "all kinds of dubious resorts had sprung up like mushrooms". Censorship had been relaxed, with the result that "Notorious magazines, which no chief of police of former times would have permitted, were sold openly on the Potzdamer Platz". Having already deplored the open display of these lmnamed publications on the streets, Shltterheim could not resist going into the "dubious resorts" to see if they were any less shocking: "An acquaintance took me into a dance-hall where painted men were dancing dressed in women's clothes. I was refused admission to another resort because it was only open to women, half of whom were dressed as men" (STUTIERHEIM, 1939, p.