Saving Mrs. Banks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCH 2021—Mary Poppins Rehearsal Schedule

MARCH 2021—Mary Poppins Rehearsal Schedule Sun Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Sat 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Ensemble Casting: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Virtual Rehearsal: 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30: TBA for Everyone in the show for Step n’ Time Dancers, for Step n’ Time Dancers, for Step n’ Time Dancers, except Mary Poppins, Chimney Sweeps, Bert, Chimney Sweeps, Bert, Chimney Sweeps, Bert, Bert, Mr. Banks, Mrs. and Mary and Mary and Mary Banks, Jane, and Michael 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Virtual Rehearsal: 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30: TBA for Step n’ Time Dancers, for All Bankers, Bank for Everyone for All Bankers, Bank Chimney Sweeps, Bert, Executive Board, Mr. Executive Board, Mr. and Mary Banks, Mr. Dawes Sr., and Banks, Mr. Dawes Sr., Mr. Dawes Jr. and Mr. Dawes Jr. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Music Rehearsal: Virtual Rehearsal: 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30-5:15 p.m.: 3:30-5:15 p.m.: 3:30-5:15 p.m.: Required 3:30: TBA for All Supercalifragilistic Required for All Required for All Jolly for All Jolly Holiday Dancers, Singers, Mary, Supercalifragilistic Holiday Characters, Bert, Characters, Bert, Mary, Mrs. -

Movies & Languages 2014-2015 Saving Mr. Banks As and Like

Movies & Languages 2014-2015 Saving Mr. Banks About the movie (subtitled version) DIRECTOR John Lee Hancock YEAR / COUNTRY 2013 / USA GENRE Comedy ACTORS T. Hanks, E. Thompson, C. Farrell, P. Giamatti PLOT Walt Disney, a doting father, promised his daughters that he would bring their favourite fictional nanny, Mary Poppins, to life in the cinema. Little did he know what he was getting into because the author of the book, Pamela Travers, did not like Hollywood and had no intention of letting her most famous creation be manipulated for the marketplace. Years later, when her book sales began to slow, dwindling finances forced her to schedule a meeting with Disney to discuss future movie rights to her beloved story. For two weeks in 1961, a determined Disney did all he possibly could to convince Travers that his film version of Mary Poppins would be wondrous and respectful. In the end, to really convince her, he had to reach back to his early childhood. LANGUAGE Standard American, Australian and British English. GRAMMAR As and Like 1. Similarity We can use like or as to say things that are similar. a. Like is a preposition. We use like before a noun or pronoun. You look like your sister He ran like the wind She's dressed like me We also use like to give examples. He's good at some subjects, like mathematics In mountainous countries, like Switzerland b. As is a conjunction. We use as before a clause, and before an expression beginning with a preposition. Nobody knows her as I do We often drink tea with the meal, as they do in China On Friday, as on Tuesday, the meeting will be at 8.30 2. -

Mary Poppins' and a Nanny's Shameful Flirting with Blackface

Linfield College DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship & Creative Works 1-28-2019 'Mary Poppins' and a Nanny's Shameful Flirting with Blackface Daniel Pollack-Pelzner Linfield College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Music Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Social History Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Pollack-Pelzner, Daniel, "'Mary Poppins' and a Nanny's Shameful Flirting with Blackface" (2019). Faculty Publications. Published Version. Submission 73. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englfac_pubs/73 This Published Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Published Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. ‘Mary Poppins,’ and a Nanny’s Shameful Flirting With Blackface Daniel Pollack-Pelzner The New York Times (Jan. 28, 2019) Copyright © 2019 The New York Times Company Julie Andrews’s soot-covered face in the 1964 film “Mary Poppins” stems from racial caricatures in books. Disney “Mary Poppins Returns,” which picked up four Oscar nominations last week, is an enjoyably derivative film that seeks to inspire our nostalgia for the innocent fantasies of childhood, as well as the jolly holidays that the first “Mary Poppins” film conjured for many adult viewers. -

“Mary Poppins Jr.” Scenes & Song

“Mary Poppins Jr.” Scenes & Song Scenes Songs ACT ONE Scene/Setting Scene 1A PROLOGUE Pgs. 1-3 #1“Prologue” Chimney Sweeps CAST: CS, B, GB,WB, J+M Scene 1B Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 4-12 #2 “Cherry Tree Lane”(Part 1) #3 “The Perfect Nanny” #4 “Cherry Tree Lane”(Part 2) CAST: KN, MB, RA, GB,WB, J+M, MP Scene 2 Cherry Tree Lane, Nursery Pgs. 13-18 #8 “Practically Perfect” CAST: J+M, MP Scene 3 PARK w/Statues Pgs. 19-29 #9 “Practically Perfect”(Playoff) #10 “Jolly Holiday” #11 “But How?” CAST: CS, B, J+M, MP, N & S, Park Strollers Scene 4A Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 30-31 CAST: GB,WB, J+M, MP Scene 4B Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pg. 32 #12 “Winds Do Change” CAST : B Scene 4C Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 33-35 CAST: MB, RA, WB, J+M, MP Scene 4D Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pgs. 36-41 #13“A Spoonful of Sugar” CAST: MB, RA, WB, J+M, MP, Bees Scene 4E Cherry Tree Lane, Parlor Pg. 41 #14“Spoonful Playoff” CAST: MB, WB Scene 5A Inside the Bank Pgs. 42-45 #15 “Precision and Order” (Part 1) #16 “Precision and Order” (Part 2) CAST: J+M, MP, GB, Mr. O, MS, Clerks, VH Scene 5B Inside the Bank Pgs. 45-48 #16 “Precision and Order” (Part 2) #17 “Precision and Order” (Part 3) CAST: J+M, MP, GB, NB Scene 5C Inside the Bank Pg. 48-49 #18 “A Man Has Dreams” CAST: GB, NB Scene 6 Outside the Cathedral Pgs. -

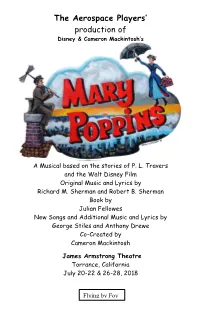

Mary Poppins Program

The Aerospace Players’ production of Disney & Cameron Mackintosh’s A Musical based on the stories of P. L. Travers and the Walt Disney Film Original Music and Lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman Book by Julian Fellowes New Songs and Additional Music and Lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe Co-Created by Cameron Mackintosh James Armstrong Theatre Torrance, California July 20-22 & 26-28, 2018 Flying by Foy Concessions Snacks and beverages are available in the lobby at intermission. 50/50 Drawing The winner receives 50% of the money collected at each performance. The winning number will be posted in the lobby at the end of each performance. Actor/Orchestra-Grams: $1 each “Wish them Luck for only a Buck” All proceeds support The Aerospace Players’ production costs – Enjoy the Show! Director’s Note On behalf of our cast and crew, I’m very excited to welcome you to The Aerospace Players’ production of Mary Poppins! The cast has been in rehearsals for almost three months now, and is thrilled to bring the show to stage, and to share it with you. Mary Poppins, despite the popularity of the 1964 movie, is only a relatively recent arrival to stage, having made its stage debut in London in 2004, then opening on Broadway in 2006, where it ran for 2,619 performances over seven years. Featuring the classic music and characters of the movie, it nonetheless reinvented and deepened the story of the Banks family, adding interesting new characters and heartfelt new music. And since no one could imagine Mary Poppins without a little “magic,” it also seems includes some special treats for the audience. -

MARY POPPINS CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS Admiral Boom: A

MARY POPPINS CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS Admiral Boom: A retired Royal Navy man and neighbor of the Banks family. A physically large man with a loud and booming voice, he speaks in Navy jargon and has a soft spot for his neighbor, Miss Lark. Can be any vocal range as needed. If Admiral Bloom doubles as the Banks Chairman, he can be a baritone. Male, 50 - 60 yrs old Bank Chairman: The head of the bank where Mr. Banks is employed, is an Edwardian stuffed- shirt. He can speak/sing his lines if necessary. Male, 50-60 yrs old Range: C3 - D4 Bert: The narrator of the story, is a good friend to Mary Poppins. An everyman, Bert has many occupations, including hurdy-gurdy player, sidewalk artist and chimney sweep. Bert watches over the children as well as the goings on in Cherry Tree Lane. He has charm, speaks with a Cockney accent and is a song-and-dance man. Male, 30 - 39 yrs old Range: B2 - F#4 Bird Woman: Covered in a patchwork of old shawls, and her pockets are stuffed with bags of crumbs for the birds. She tries to sell her crumbs for the birds. She tries to sell her crumbs to passersby, who ignore her as if she doesn't exist. Sings "Feed the Birds." There can be a gruff, folksy quality to her voice that reflects the hardness of her life. Female, 50 - 60 yrs old Range: Gb3 - C5 Ensemble George Banks: The father to Jane and Michael Banks, is a banker to the very fiber of his being. -

Mary Poppins Characters

Mary Poppins Characters Mary Poppins Jane and Michael Banks's new nanny. She is extraordinary and strange, neat and tidy, delightfully vain yet particular, and sometimes a little frightening but always exciting. She is practically perfect in every way and always means what she says. Bert The narrator of the story is a good friend to Mary Poppins. An everyman, Bert has many occupations, including hurdy-gurdy player, sidewalk artist and chimney sweep. He has charm, speaks with a Cockney accent and is a song-and-dance man. George Banks The father to Jane and Michael Banks is a banker to the very fiber of his being. He demands "precision and order" in his household. His emotional armor, however, conceals a sensitive soul. Winifred Banks George's wife and Jane and Michael's mother. She is a loving and distracted homemaker, and she suffers from the conflicting feelings that she's not up to the job of "Being Mrs. Banks," yet, she is, and more. She has great warmth and simplicity to her tone. Jane The high-spirited daughter of Mr. and Mr. Banks is bright and precocious but can be willful and inclined to snobbishness. Age: 10-12 Michael The cute and cheeky son of Mr. and Mrs. Banks is excitable and naughty. He adores his father and tries to be like him. Age: 10-12 Mrs. Brill The housekeeper and cook for the Banks family. Overworked, she's always complaining that the house is understaffed. Her intimidating exterior is a cover for the warmth underneath. Robertson Ay The houseboy to the Banks family. -

Cast Size: Large (Over 20) Character Breakdown: MARY POPPINS Jane

Cast size: Large (over 20) Character Breakdown: MARY POPPINS Jane and Michael Banks's new nanny. She is extraordinary and strange, neat and tidy, delightfully vain yet very particular, and sometimes a little frightening but always exciting. She is practically perfect in every way and always means what she says. A mezzo soprano with strong top notes, she should be able to move well. She can have a more traditional soprano sound, but precision and diction is the key. Female, 20-30 yrs old Range: Gb3 - C6 _____________________________________________________________________________________ BERT The narrator of the story, is a good friend to Mary Poppins. An everyman, Bert has many occupations, including hurdy-gurdy player, sidewalk atist, and chimney sweep. Bert watches over the children as well as the goings on in Cherry Tree Lane. He has charm, speaks with a Cockney accent, and is a song-and-dance-man. Male, 30-39 yrs old Range: B2 - F#4 _____________________________________________________________________________________ GEORGE BANKS The father to Jane and Michael Banks, is a banker to the very fiber of his being. Demanding "precision and order" in his household, he is a pipe-and-slippers man who doesn't have much to do with his children and believes that he had the perfect upbringing by his nanny, the cruel Miss Andrew. His emotional armor, however, conceals a sensitive soul. A baritone, George may speak- sing as necessary. Male, 40-45 yrs old Range: Bb2 - Eb4 _____________________________________________________________________________________ WINIFRED BANKS George's wife and Jane and Michael's mother. A former actress, she is a loving and distracted homemaker who is busy trying to live up to her husband's desire to only associate with "the best people" as well as be a model wife and mother. -

Mary Poppins

MARY POPPINS Mary Poppins is a musical with music and lyrics by Richard M. Sherman and Robert B. Sherman, with additional music and lyrics by George Stiles and Anthony Drewe, and a book by Julian Fellowes. The musical is based on a series of children's books by P. L. Travers and the 1964 Disney film, and is a fusion of various elements from the two. Produced by Walt Disney Theatrical and Cameron Mackintosh, and directed by Richard Eyre with co-direction from Matthew Bourne who also acted as co-choreographer with Stephen Mear, the original West End production opened in December 2004 and received two Olivier Awards, one for Best Actress in a Musical and the other for Best Theatre Choreography. Following the success of the West End production, a Broadway production with a nearly identical creative team debuted on November 16, 2006 at the New Amsterdam Theatre. Broadway performer Ashley Brown was brought on board to play the title role, and Gavin Lee, who had originated the role of Bert in the West End production, reprised his role in the Broadway production. From the “Mary Poppins Education Series – The Magic of Mary”: “To create the magic used in Mary Poppins, the producers turned to celebrated theatrical illusionist Jim Steinmeyer – famous for his work with magicians, including David Copperfield and Siegfried & Roy - and for the flying effects, the legendary Flying by Foy, who have set new standards for flying on the Broadway stage for over 50 years.” Ashley Brown: “I wasn’t flown for the first time until about two weeks before we opened in New York…and it’s really become one of my favorite moments, because I can see the faces of the people for the first time, and just see how everybody is reacting.” Gavin Lee: “When I walk around the proscenium arch and tap dance and sing upside down, I can hear the audience every night, applauding, the kids gasping and pointing up there and it’s just a thrill to be able to do this magical sort of trick.” We’ve found a whole new spin… …if you reach for the heavens, you get the stars thrown in! We Love to See You Fly. -

Mary Poppins Character List

Character List Below you will find a description of each character that you can audition for. Please remember although you are only selecting two roles to audition for, you will be considered all roles. Please use the GA website to find the script and song that you will use for your audition as well as the recordings to practice with. All singing needs to be done in head voice. There should be no belting in this musical. Ensemble - All ensembles require group singing; featured roles require either solo singing or solo acting, or both. For each featured role, the pages showcasing the character's lines or vocals are listed. Ensemble & Featured Characters include: Katie Nanna, Park Strollers, Statues, Neleus, Bird Woman, Honeybees, Clerks, Miss Smythe, Chariman, Von Hussler, John Northbrook, Vagrants, Buskers, Passerby, Mrs. Corry, Customers, Miss Andrew, Kite Flyers, Chimney Sweeps, Policeman and the Messenger. Bert (male or female) - The narrator of the story, is a good friend to Mary Poppins. An everyman, Bert is a chimney sweep and a sidewalk artist, among many other occupations. With a twinkle in his eye and a skip in his step, Bert watches over the children and the goings-on around Cherry Tree Lane. He is a song-and-dance man with oodles of charm who is wise beyond his years. Must do a dance audition for this part! Must be a strong singer! Mary Poppins (female) - Jane and Michael Banks’s new nanny. She is extraordinary and strange, neat and tidy, delightfully vain yet very particular, and sometimes a little frightening, but she is always exciting. -

Study Guide ORIGINAL MUSIC and LYRICS by RICHARD M

©Disney/CML A MUSICAL BASED ON THE STORIES OF P.L. TRAVERS AND THE WALT DISNEY FILM study guide ORIGINAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY RICHARD M. SHERMAN AND ROBERT B. SHERMAN Prepared by Disney Theatrical group Education Department BOOK BY JULIAN FELLOWES NEW SONGS AND ADDITIONAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY GEORGE STILES AND ANTHONY DREWE CO-CREATED BY CAMERON MACKINTOSH intro - welcome Anything can happen if we recognize In Mary Poppins, the factory owner John Northbrook tells Michael that money has a worth (for example, one dollar or, in London, one the magic of everyday life. Author P.L. Travers pound) but it also has a value (or what the money can do to help understood this special kind of magic when she published her first others). Mary Poppins teaches the Banks family (and the audience!) book, Mary Poppins, in 1934. The tale of the mysterious nanny who to value the important things in life: family, friendship and teaches a troubled family to appreciate the important things in life imagination. In Mary Poppins, Mary sings, Anything can happen if went on to become one of the most recognized and beloved stories you let it. Mary Poppins is about discovering the extraordinary world of all time. Thirty years later, Walt Disney released the film based around us, even when things look bleak. This guide is designed to on Travers' stories: a unique mixture of animation and live action help you explore the extraordinary world of Mary Poppins. that has become a classic. Now Mary Poppins flies over audiences and lands on a Disney BROADEN YOUR HORIZON Broadway stage, complete with new songs and breathtaking theatrical magic. -

The Subversive Mary Poppins: an Alternative Image of the Witch in Children’S Literature

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 2, Issue 6, June 2014, PP 31-40 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) www.arcjournals.org The Subversive Mary Poppins: An Alternative Image of the Witch in Children’s Literature 1Li-ping Chang, 2Yun-hsuan Lee, 3Cheng-an Chang Department of Applied Foreign Languages National Taipei College of Business Taipei, Taiwan [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Pamela Lyndon Travers was born in Australia, pursued her writing career in England, and became world famous in children’s literature for her books about Mary Poppins. Mary Poppins was adapted for film in 1964, and later for the stage. In the character of Mary Poppins, Travers subverted the stereotype of the witch as evil. Unlike conventional portrayals of witches that were based on the Christian church’s demonization of powerful women in the Middle Ages, Mary Poppins is not a cannibalistic hag, but both nanny and teacher to her charges. That she is a caretaker of children does not lessen her magical power. This article explores the witch’s place in history and in fairy tales, and how Travers subverted the negative stereotype through Mary’s dual role as nanny and witch, taking into account Maureen Anderson’s ideas on the metaphor of the witch, Cristina Pérez Valverde’s discourse on the marginalization of women, and Sheldon Cashdan’s theory on the function of the witch in fairy tales. Mary’s magical powers give the Banks’ children a new perspective and philosophy of life; drawing on mythic figures from a pre-Christian era, Travers’s storytelling magic does the same for young readers.