Carbon Mitigation Potential on Community Lands (Van Panchayats)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EFFECTIVENESS of FUND ALLOCATION and SPENDING for the NATIONAL RURAL HEALTH MISSION in UTTARAKHAND, INDIA Block and Facility Report

EFFECTIVENESS OF FUND ALLOCATION AND SPENDING FOR THE NATIONAL RURAL HEALTH MISSION IN UTTARAKHAND, INDIA Block and Facility Report March 2014 HEALTH POLICY PROJECT The Health Policy Project is a five-year cooperative agreement funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Agreement No. AID-OAA-A-10-00067, beginning September 30, 2010. The project’s HIV activities are supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). It is implemented by Futures Group, in collaboration with CEDPA (part of Plan International USA), Futures Institute, Partners in Population and Development, Africa Regional Office (PPD ARO), Population Reference Bureau (PRB), RTI International, and the White Ribbon Alliance for Safe Motherhood (WRA). Effectiveness of Fund Allocation and Spending for the National Rural Health Mission in Uttarakhand, India Block and Facility Report The document was prepared by Catherine Barker, Alexander Paxton, Ashish Mishra, and Arin Dutta of the Health Policy Project, and Ayusmati Das and Jay Prakash of the Policy Unit, NIHFW. MARCH 2014 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. v Phase 2 Study Findings ............................................................................................................................. v Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... -

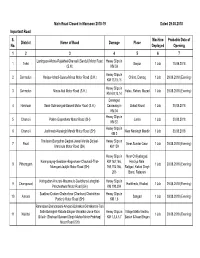

S. No. District Name of Road Damage Place Machine Deployed Probable

Main Road Closed in Monsoon 2018-19 Dated 29.08.2018 Important Road S. Machine Probable Date of District Name of Road Damage Place No. Deployed Opening 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Lambgaon-Motna-Rajakhet-Ghansali (Sendul) Motor Road Heavy Slips in 1 Tehri Sarpur 1 Jcb 10.09.2018 (S.H.) KM 59 Heavy Slips in 2 Dehradun Haripur-Ichadi-Quanu-Minus Motor Road (S.H.) Chibro, Damog 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) KM 13,15,16 Heavy Slips in 3 Dehradun Minus-Atal Motor Road (S.H.) Hateu, Rehan, Mazad 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) KM 4,8,13,14 Damaged 4 Haridwar Sarai-Subhashgad-Basedi Motor Road (S.H.) Causeway in Ekkad Khurd 1 Jcb 30.08.2018 KM 04 Heavy Slips in 5 Chamoli Pokhri-Gopeshwar Motor Road (SH) Jumla 1 Jcb 30.08.2018 KM 52 Heavy Slips in 6 Chamoli Joshimath-Narsingh Mandir Motor Road (SH) Near Narsingh Mandir 1 Jcb 30.08.2018 KM 2 Thailisain-Bungidhar-Deghat-Jainal-Manila-Dotiyal- Heavy Slips in 7 Pauri Near Sundar Gaon 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) Marchula Motor Road (SH) KM 159 Heavy Slips in Near Chiliyabagad, Karanprayag-Gwaldam-Bageshwer-Chaukadi-Thal- KM 162,166, Hardiya Nala, 8 Pithoragarh 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) Munsyari-Jauljibi Motor Road (SH) 169,174,166, Ratigad, Kakad Singh 206 Band, Ratapani Kathgodam-Khutani-Maurnaula-Devidhura-Lohaghat- Heavy Slips in 9 Champawat Harikheda, Khaikot 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) Pancheshwar Motor Road (SH) KM 192,204 Suakhan-Dodam-Chalnichina (Chadounj-Chalnichina Heavy Slips in 10 Almora Sangad 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) Portion) Motor Road (SH) KM 1,6 Ramnagar-Bhandarpani-Amgadi-Bohrakot-Okhalkanda-Talli Sethi-Betalghat-Ratoda-Bhujan-Vishalkot-Jaina-Richi Heavy Slips in Village Malla Vardho, 11 Nainital 1 Jcb 29.08.2018 (Evening) Billekh (Sheheed Balwant Singh Mehra Motor Prabhag) KM 1,3,4,6,7 Baderi & Near Bhujan Motor Road (SH) Main Road Closed in Monsoon 2018-19 Dated 29.08.2018 Important Road S. -

Ground Water Scenario of Himalaya Region, India

Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region, India laiknu@Edited By: lq'khy xqIrk v/;{k Sushil Gupta Chairman Central Ground Water Board dsanzh; Hkwfe tycksMZ Ministry of Water Resources ty lalk/ku ea=kky; Government of India Hkkjr ljdkj 2014 Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k dk Hkwty ifjn`'; vuqØef.kdk dk;Zdkjh lkjka'k i`"B 1- ifjp; 1 2- ty ekSle foKku 23 3- Hkw&vkd`fr foKku 34 4- ty foKku vkSj lrgh ty mi;kst~;rk 50 5- HkwfoKku vkSj foorZfudh 58 6- Hkwty foKku 73 7- ty jlk;u foKku 116 8- Hkwty lalk/ku laHkko~;rk 152 9- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k esa Hkwty fodkl ds laca/k esa vfHktkr fo"k; vkSj leL;k,a 161 10- Hkkjr ds fgeky;h {ks=k ds Hkwty fodkl gsrq dk;Zuhfr 164 lanHkZ lwph 179 Ground Water Scenario of Himalayan Region of India CONTENTS Executive Summary i Pages 1. Introduction 1 2. Hydrometeorology 23 3. Geomorphology 34 4. Hydrology and Surface Water Utilisation 50 5. Geology and Tectonics 58 6. Hydrogeology 73 7. Hydrochemistry 116 8. Ground Water Resource Potential 152 9. Issues and problems identified in respect of Ground Water Development 161 in Himalayan Region of India 10. Strategies and plan for Ground Water Development in Himalayan Region of India 164 Bibliography 179 ifêdkvks dh lwph I. iz'kklfud ekufp=k II. Hkw vkd`fr ekufp=k III. HkwoSKkfud ekufp=k d- fgeky; ds mRrjh vkSj if'peh [kaM [k- fgeky; ds iwohZ vkSj mRrj iwohZ [kaM rFkk iwoksZRrj jkT; IV. -

Name, Mobile & Working Place of Plvs

DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICE AUTHORITY, NAINITAL Name, Mobile & Working Place of PLVs S.N. Name of PLV Mobile No. Working Place/Area 1 Ishwari Dutt 7500923821 Haldwani 2 Bhuwan Chandra Tiwari 8954754152 Haldwani 3 Ganesh Singh Pokhariya 9411597361 Nainital 4 Shambhu Dutt Chemwal 9536824697 Ramnagar 5 Neema Parihar 9837092673 Nainital 6 Ganesh Chandra 8650665216 Nainital 7 Neema Upreti 8979156803 Nainital 8 Nikhil Prasad 9690277122 Nainital 9 Hema Devi 9456384432 Nainital 10 Prakash Chandra Tripathi 9411366233 Haldwani 9410119275 11 Neeta Sammal Nainital 9456509473 12 Kamini Mehra 8958454945 Nainital 9756807267 13 Krishna Chandra Nainital 9675540554 14 Kamal Kumar 9012556862 Nainital 15 Neha Arya 9568759261 Nainital 16 Reeta Pandey 9690881754 Nainital 17 Rajendra Singh Mehra 7088966126 Nainital 18 Lal Singh 7088746677 Nainital 19 Anand Prakash 7830354350 Nainital 20 Manju Arya 9410721572 Nainital 21 Girdhari Singh Mahra 9536949145 Nainital 22 Dinesh Chandra Lweshali 9719101865 Haldwani 23 Godawari Goswami 7060168347 Ramnagar 9458937881 24 Sunita Devi Okhalkanda 7055744773 25 Pooran Chandra 9410942485 Betalghat 9458186401 26 Bhuwan Chandra Okhalkanda 9690744942 27 Dinesh Chandra Tewari 9456780536 Haldwani 7302002879 28 Mohit Kumar Nainital 8430535330 29 Umesh Kumar Arya 9456779292 Nainital 30 Neema Arya 7830535972 Jyolikot 7409802715 31 Laxmi Arya Bhowali 9458153776 32 Dinesh Chandra Joshi 9411773463 Haldwani 33 Asif Khan 9012395309 Haldwani 34 Uma Bhandari 9410375486 Haldwani 35 Kailash Chandra 8477051421 Ramnagar 36 Manas Pant 9756455133 Haldwani -

Directory of E-Mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server

Directory of E-mail Accounts of Uttarakhand Created on NIC Email Server Disclaimer : For email ids enlisted below, the role of NIC Uttarakhand State Unit is limited only as a service provider for technical support for email-ids created over NIC’s Email Server, over the demand put up by various Government Depratments in Uttarakhand from time to time. Therefore NIC does not take responsibility on how an email account is used and consequences of it’s use. Since there may also be a possibility that these Departments might be having varied preferences for using email ids of various service providers (such as yahoo, rediffmail, gmail etc etc) other than NIC email ids for various official purposes. Therefore before corresponding with an email over these accounts, it is advised to confirm official email account directly from the department / user. As per policy NIC's email account once not used continuously for 90 days gets disabled. Last Updated on :- 25/10/2012 DEPARTMENT DESIGNATION HQs EMAIL-ID DESCRIPTION Accountant General Accountant General State Head Quarter [email protected] Accountant General(A & E) Agriculture Hon'ble Minister State Head Quarter [email protected] Minister of Agriculture, GoU Agriculture Secretary State Head Quarter [email protected] Secretary, GoUK Aditional Director of Agriculture Aditional Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy Director Technical Analysis of Agriculture Deputy Director State Head Quarter [email protected] Agriculture ,Dehradun,Uttarakhand Deputy -

No.8-35/2012-Leadership Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs

0 63 .217(4' No.8-35/2012-leadership Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs 11th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, C.G.O.Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 Dated: 19th ecember, 2012 To The Pay & Accounts Officer, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi Subject: Release of 1 st installment (70%) of non-recurring Grant-in-Aid for the year 2012-13 to `Manav Sewa Samaj, Main Bazar Betalghat, Block & Tehsil Betalghat, District Nainital, Uttarakhand' for organizing Leadership Development training programme at Dehradun District (Uttarakhand) under the "Scheme for Leadership Development of Minority Women". Sir, I am directed to convey the sanction of the President of India for an amount of Rs. 2,14,650/- (Rupees Two Lakh Fourteen Thousand Six Hundred And Fifty only), towards the cost for organizing Leadership Development training for Minority Women for 75 (Seventy Fifty only) Non-Residential for selected trainees at Dehradun District (Uttarakhand) and release of Rs. 1,50,255/- (Rupees One Lakh Fifty Thousand Two Hundred And Fifty Five only) for Non—Residential as first installment(70%) during the year 2012-13, Manav Sewa Samaj, Main Bazar Betalghat, Block & Tehsil Betalghat, District Nainital, Uttarakhand, as per details at Annexure — I. The above sanction is subject to fulfillment of following terms and conditions as given in para 2 (i-xii) and the Guidelines prescribed under the Scheme: 2 (i) Grant-in-aid has been given to the above mentioned organizations on the basis of the recommendation of Government of Uttarakhand. It is incumbent on the part of Government of Uttarakhand to ensure that the organization recommended by them utilize the fund for the purpose it has been sanctioned. -

58- Nainital Uttarakhand a Defence Service Part No

Electoral Roll. 2012 Assembly Constituency ;58- Nainital Uttarakhand A Defence Service Part No 146 S.N. Elector Name Electo Rank Husb Dispatch House address r and Address Type Sl.No. 1 2 3 4 5 7 8 1 ANAND SINGH M NK 4191834L VILLAGE.MAUNA BHANDARI RECORDS THE KUMAON KHAIRNA REGIMENT RANIKHET TEHSIL, KOSHIYA KUTOLI DISTT. NAINITAL 2 ANAND SINGH NEGI M SEP 4194221 VILLAGE. RECORDS THE KUMAON MAUNAKHAIRNA REGIMENT RANIKHET TEHSIL, KOSHIYA KUTOLI DISTT. NAINITAL 3 ANAND SINGH M HC/G 763430092 VILLAGE SIMALKHA BHANDARI D C.I.S.F OTHAPPOBRA TEHSIL, DHARI SONEBHDRA(UP) DISTT. NAINITAL 4 KAMLA DEVI F 3 763430092 VILLAGE SIMALKHA C.I.S.F OTHAPPOBRA TEHSIL, DHARI SONEBHDRA(UP) DISTT. NAINITAL 5 BALWANT SINGH M SEP 4194341P VILLAGE .RATOURA RECORDS THE KUMAON TEHSIL, LALKUAN REGIMENT RANIKHET DISTT. NAINITAL 6 BAGAMBER SINGH M LNK 13618531X VILLAGE. RATOURA RECORDS THE PARA P.O. UNCHAKOTE REGIMENT BANGLORE TEHSIL, KOSHIYAKUTOLI DISTT. NAINITAL 7 DEEPA F 6 13618531X VILLAGE. RATOURA RECORDS THE PARA P.O. UNCHAKOTE REGIMENT BANGLORE DISTT. NAINITAL 8 BHUPENDRA SINGH M GNR 15769881N VILLAGE. RATOURA BISHT AD. ARTY RECORDS P.O. UNCHAKOTE 509/GAY/501/ADIER4NPC TEHSl,KOSIYAKUTOLI DISTT. NAINITAL 9 BACHI SINGH M HAV 4175097L VILLAGE. THAPLI RCORDS THE KUMAON TALLA BARDA REGIMENT RANIKHET TEHSIL, NAINITAL DISTT. NAINITAL 10 ASHA DEVI F 9 4175097L VILLAGE. TALLA RCORDS THE KUMAON BARDA REGIMENT RANIKHET TEHSIL, NAINITAL DISTT. NAINITAL 11 BALWANT SINGH M HAV/ 8430180N VILLAGE. TALLA CLK RECORDS TJHE APS BARDA RECORDS C/O 56 APO TEHSIL, NAINITAL DISTT. NAINITAL 12 DAYA MEHRA F 11 8430180N VILLAGE. -

Nainital-CSC VLE Details

VLEs Details -Common Service Center, District-Nainital SN District Tehsil Block VLE Name Contact Number Panchayat NayalidankiniyaAddress Ramgar Nayalidankiniya Ramgar 1 NAINITAL Nainital ramgarh Birendra Singh Negi 9927307070 Dankanya Nainital Uttrakhand 2 NAINITAL Nainital Bhimtal Mamta Kumaiyan 9412035406 \N 56 TALLITAL BAZAAR OPPOSITE HIMALAYA HOTEL 3 NAINITAL Haldwani haldwani Najmul Hasan Siddiqui 8909464109 \N nainital haldwani 4 NAINITAL Haldwani haldwani Bhagwati Devi 9627959007 Gujrauda 5 NAINITAL Kosya Kutauli betalghat Pankaj Kumar 9720514995 Ulgor Lohali Ulgor Gic Inter College Lohali 6 NAINITAL Ramnagar ramnagar Mohhd Nazim 9837291091 \N GULARGHATTI 7 NAINITAL Haldwani haldwani Mohammad Adnan 9458920786 \N LINE NO 17 AZAD NAGAR 8 NAINITAL Dhari okhalkanda Kamal Singh 9458938442 Timmar Okhalkanda Teemar Okhalkanda 9 NAINITAL Ramnagar ramnagar Shahzad 8171151719 \N indra colony near bus station 10 NAINITAL Lalkuan haldwani Sanjay Kumar Bhatt 9760553883 Bametabangar Keshavdatt NEARNARAYAN SHIVE PURAM MANDIR BAMATHA UNCHAPUL BANGAR HARINAGAR KESHAV 11 NAINITAL Haldwani haldwani Prakash Singh Mehta 9837420003 Himmatpur Malla HARIPURNAYAK 12 NAINITAL Kaladhungi kotabagh Kavindra Singh Bisht 8938064717 Gulrajpur Banki GULJARPUR RAMSINGH CHAKLUWA 13 NAINITAL Lalkuan Haldwani Manoj Kumar Prajapati 9760208312 \N 25 ACER COLONY LALKUAN 14 NAINITAL Ramnagar ramnagar Mohammad Adil 9690690956 \N Chappar Wali Masjid 15 NAINITAL Ramnagar ramnagar Mohd Rawish 8958060735 \N Manglar Road Gularghatti 16 NAINITAL Kaladhungi kotabagh Moh Suhel -

Appendix IV IERP PROJECT ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2016-17 Period from 1St April 2016 to 31St March 2018

Appendix IV IERP PROJECT ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT 2016-17 Period from 1st April 2016 to 31st March 2018 1. Project Title: “Ecological, Taxonomical and Ethnobotanical Study of Wild Edible Plants of Nainital District in Uttarakhand, India” 2. Name of Principal Investigator Dr. Lalit M. Tewari, Professor, Department of Botany, D. S. B. Campus, Kumaun University Nainital 263002; Uttarakhand, India Email: [email protected] Co- Principal Investigator(s) i) Dr. Ashish Tewari Assistant Professor Department of Forestry & Environmental Sciences D. S. B. Campus, Kumaun University, Nainital , 263002, Uttarakhand, India Email: [email protected] ii) Dr. Geeta Tewari Assistant Professor Department of Chemistry D. S. B. Campus, Kumaun University, Nainital, 263002, Uttarakhand, India Email: [email protected] Project staff Neha Chopra, JPF, Research Scholar, Department of Botany, D. S. B. Campus, KU Nainital 3. GBPIHED project sanction letter no. & Date of sanction: Letter No. GBPI/IERP- NMHS/16-16/48/14 dated: 31st March 2016 4. Total outlay sanctioned- Rs. 13, 60000/-(Thirteen lakh sixty thousand only) 4.1 Duration: 3 years 5. Date of start: 1st April 2016 6. Grant received during the year: 2016-17 Rs. 4, 97,000/- (Four lakh ninety seven thousands) 1 7. Expenditure incurred during the year: 2017-18 Copy of utilization certificate is attached with progress report as Annexure I. 8. Broad area of research: Ecological, Taxonomical and Ethnobotanical Study of Wild Edible Plants 9. Sub area of the project: Distribution, and nutrient analysis of wild edible plants 10. Approved objectives of the project: 1. Identification and taxonomic description of all wild edible plants distributed in the study areas with their relevant names and habitat distribution. -

Diversity of Legumes of Betalghat, Kumaun, Western Himalaya

ISSN (online): 2320-4257 8(2):1-9 www.biolifejournal.com AN INTERNATIONAL QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY & LIFE SCIENCES B I O L I F E O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Diversity of Legumes of Betalghat, Kumaun, Western Himalaya Naveen Chandra Pandey1* Neha Chopra2, G.C. Joshi3 and Lalit M. Tewari4 1,2,4 Department of Botany, D.S.B. Campus, Kumaun University, Nainital, Uttarakhand. 3 Regional Ayurvedic Research Institute (RARI), CCRAS, Ranikhet, Uttarakhand. E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT The Indian Himalaya is rich in socio-cultural values, biodiversity and having a vast treasure of medicinal plant. Uttarakhand is a part of Indian Himalayan Region, has vast number of rivers, tributaries and lakes. Betalghat is a block of Nainital district located at the bank of river Kosi. The study was conducted to document the diversity of Legumes of Betalghat, Kumaun, Western Himalaya. Total 127 plants species belonging to 55 genera of different habits such as herbs (65 species) dominates the area followed by shrubs (33 species), trees (18 species), and climbers (11 species) were recorded. The preserved plant specimens were deposited in the herbarium division of the Department of Botany, D.S.B. Campus, Kumaun University, Nainital. Key words: Diversity, Fabaceae (Legumes), Betalghat, Kumaun, Western Himalaya. pea or bean families, consisting of all trees, shrubs and herbaceous plants perennials or annuals, which can be INTRODUCTION easily identified by their fruits (legume) and compound, stipulated leaves (Kajita et al., 2001, Judd et al., 2002, The Indian Himalaya is rich in socio-cultural values, Stevens, 2008, Sprent, 2009, Lewis et al., 2005, Rahman biodiversity and having a vast treasure of medicinal et al., 2014, Noreen et al., 2018). -

A Critical Study on Kumaun Lesser Himalaya

Anthropogenic induced activities on Water resource with special reference to Bhimtal and its Environ; A critical study on Kumaun Lesser Himalaya. Kedovikho Yhoshü Department of Geography, Nagaland University- 798627 Abstract: The mounting pressures of anthropogenic activities have taken its toil on nature and nature is gradually degrading in the blunt ways of man with a cost to the pristine ecology. To study the affect of anthropogenic activities on the water ecosystem in the fragile Himalayan Ecosystem, a case study has been taken by selecting Bhimtal town and eleven satellite villages surrounding it. The study region is located in Uttarakhand state under Nainital district and comes under Nagthat geologic formation. The study region has the largest lake namely- Bhimtal lake in the entire Lake region. Being a part of the Himalaya, the study region is in a fragile environment where more destruction are rising with the increase of building activities, modernisation, deforestation, pollution level, etc. Some of the anthropogenic activities especially tourism has been considered along with the anthropogenic landuse pattern system to analyse the degrading environment in Bhimtal and its Environ especially in regard to water resources. The boon of tourism in the state has led to drastic change in the economy as well as the ecology of the lake region. The once agricultural land has now being replaced by the resorts, recreational centres, etc. This crucial matter has been highlighted by pinpointing the destruction process of the environment. Keywords: Ecosystem; Drainage; landuse; water resource; tourism; environmental hazard Introduction The Study Region comprises of one urban centre-Bhimtal and eleven satellite villages. -

Nainital, Uttarakhand

District Profile Nainital, Uttarakhand The Nainital district has eight tahsils Kosyakutauli, Nainital, Dhari, Betalghat, Ramnagar, Kaladhungi, Haldwani and Lalkuan, out of which Betalghat, Ramnagar, Kaldhungi and Lalkhuan are new tahsils created. The district has 1141 villages, 1097 are inhabited and 44 are uninhabited. There are 11 towns. The total area in the district is 4251 sq.km. DEMOGRAPHY As per Census 2011, the total population of Nainital is 954,605, out of which 493,666 were males and 460,939 were females. This gives a sex ratio of 934 fe- males per 1000 males. The percentage of urban population in the district is 38.94 percent, which is higher than the state average of 30.23 percent. The deca- dal growth rate of population in Uttarakhand is 18.81 percent, while Nainital reports a 25.13 decadal growth in the population. The decadal growth rate of ur- ban population in Uttarakhand is 39.93 percent, while Nainital reports a 38.17 percent. The district population density is 225 in 2011. The Scheduled Caste popu- lation in the district is 20.03 percent while Scheduled Tribe comprises 0.79 percent of the population. LITERACY The overall literacy rate of Nainital district is 83.88 percent while the male & female literacy rates are 90.07 percent and 77.29 percent respectively. At the block level, a considerable variation is noticeable in male-female literacy rate. Ramnagar has the lowest literacy male at 86.01 percent and Dhari has the lowest female rate at 68.26 percent. Nainital has the highest male and female literacy rates at 94.8 percent and 80.08 percent respectively.