WINTER 2016 THIS ISSUE • Formation • Breathe • Formed for a Purpose • Spiritual Formation: a Life-Long Quest from the Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love & Wedding

651 LOVE & WEDDING THE O’NEILL PLANNING RODGERS BROTHERS – THE MUSIC & ROMANCE A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR YOUR WEDDING 35 songs, including: All at PIANO MUSIC FOR Book/CD Pack Once You Love Her • Do YOUR WEDDING DAY Cherry Lane Music I Love You Because You’re Book/CD Pack The difference between a Beautiful? • Hello, Young Minnesota brothers Tim & good wedding and a great Lovers • If I Loved You • Ryan O’Neill have made a wedding is the music. With Isn’t It Romantic? • My Funny name for themselves playing this informative book and Valentine • My Romance • together on two pianos. accompanying CD, you can People Will Say We’re in Love They’ve sold nearly a million copies of their 16 CDs, confidently select classical music for your wedding • We Kiss in a Shadow • With a Song in My Heart • performed for President Bush and provided music ceremony regardless of your musical background. Younger Than Springtime • and more. for the NBC, ESPN and HBO networks. This superb The book includes piano solo arrangements of each ______00313089 P/V/G...............................$16.99 songbook/CD pack features their original recordings piece, as well as great tips and tricks for planning the of 16 preludes, processionals, recessionals and music for your entire wedding day. The CD includes ROMANCE: ceremony and reception songs, plus intermediate to complete performances of each piece, so even if BOLEROS advanced piano solo arrangements for each. Includes: you’re not familiar with the titles, you can recognize FAVORITOS Air on the G String • Ave Maria • Canon in D • Jesu, your favorites with just one listen! The book is 48 songs in Spanish, Joy of Man’s Desiring • Ode to Joy • The Way You divided into selections for preludes, processionals, including: Adoro • Always Look Tonight • The Wedding Song • and more, with interludes, recessionals and postludes, and contains in My Heart • Bésame bios and photos of the O’Neill Brothers. -

000000000000Oo1(1Gnn Ro T P a . 1 F 000000

HE NOMINEES ARE IN! It's ime To Vote For R & ''s Industry Achievement Award The Industry's Brightest Personalities, Finest Radio Stations, Most With -It Label A S OF SMOOTH JAZZ IN Execs And Best Record CHICAGO, SAN FRAN, CLEVELAND .e..- e TR! CAPITOL CHAIRMAN JASON WILL RADIO PAY ARTISTS LOM ON THE FUTURE OF THE BIZ AND LABELS? IlkRHYTHMIC: POWER 106 /L.A: S BIG BOY INKS SYNDIE DEAL WITH ABC s roues, = roa tas ers Take Performance -Rights Fight RADIO & RECORDS AIENT: SECRETS TO LAUNCHING A To Congress p.18 NEW PERSONALITY SHOW AUGUST 17, 2007 NO. 1723 $6.50 www.RadioandRecords.com ADVERTISEMENT "If you're a male PD and you're not hearing this song, that's a great thing since the Backstreet Boys aren't singing it for you! Ask your wife, girlfriend, or any in -demo woman what THEY think. The results will speak for themselves! I am getting MAD requests with the demo! " -TOBY KNAPP, WFLZ /TAMP^ "Still Backstreet! Still relevant! Still in demand: #1 PHONES AT Z100!" -ROMEO, MD, Z 1 00/NEW YORK "Girls like listening to WFLZ. Girls like the Backstreet Boys. Yay for girls! "Inconsolable" sounds great on the air!" TOMMY CHUCK, PD, WFLZ /TAMPA i o C 111 bockSTREEF 000000000000oo1(1Gnn ro t P A. 1 F 000000 Early Majors Include: 2100! WIHT! KZHT! WFLZ! WBLI! KZZP! WPRO! WQAL! #1 Phones: Z 1 ON Impacting Pop & Hot AC Radio August 27th! From The Album Unbreakable In Stores October 4* NM www.backstreetboys.com www.zombalabelgrcup.com (0 2007 Zomba Recording (LC www.americanradiohistory.com BDSCertified Spin Awards August 2007 Recipients: 800,000 SPINS If You're Gone/ Matchbox Twenty /Atlantic 700,000 SPINS Bring Me To Life/ Evanescent !Wind -Up 600,000 SPINS -1979 -/ SmdSIuny Pumpkins /Virgin From This Moment On/ Shania Twain /Mercury B R O D C S T D A T A S Y S T E M A A Hero / Heroe/ Enrique Iglesias /Interscope /Universal Latino Ironic/ Alanis Morissette /Maverick 500,000 SPINS Come Down/ Bush /Trauma Crazy In Love/ Beyonce /Columbia I Try/ Macy Gray /Epic 400,000 SPINS Before He Cheats/ Carrie Underwood /Arista /Arista Nashville Check On It/ Beyonce Feat. -

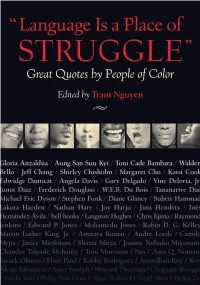

"Language Is a Place of Struggle" : Great Quotes by People of Color

“Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” “Language Is a Place of STRUGGLE” Great Quotes by People of Color Edited by Tram Nguyen Beacon Press, Boston A complete list of quote sources for “Language Is a Place of Struggle” can be located at www.beacon.org/nguyen Beacon Press 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 2009 by Tram Nguyen All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 12 11 10 09 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Text design by Susan E. Kelly at Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Language is a place of struggle : great quotes by people of color / edited by Tram Nguyen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8070-4800-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Minorities—United States—Quotations. 2. Immigrants—United States—Quotations. 3. United States—Race relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 4. United States—Ethnic relations—Quotations, maxims, etc. 5. United States—Social conditions—Quotations, maxims, etc. 6. Social change—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 7. Community life—United States—Quotations, maxims, etc. 8. Social justice—United States— Quotations, maxims, etc. 9. Spirituality—Quotations, maxims, etc. I. Nguyen, Tram. E184.A1L259 2008 305.8—dc22 2008015487 Contents Foreword vii Chapter 1 Roots -

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

Lenten Reader 2018 Booklet for Print.Pub

PO Box 23117 | RPO McGillivray | Winnipeg, MB R3T 5S3 Ph. 204-269-3437 Fx. 204-269-3584 www.covchurch.ca Editors: Julia Sandstrom Hanne Johnson LENTEN READER 2018 A COMPILATION OF REFLECTIONS ON SCRIPTURE FOR THE SEASON OF LENT FROM MEMBERS OF THE EVANGELICAL COVENANT CHURCH OF CANADA Printed copies of the Lenten Reader are made possible by funding from Trellis Foundation. We are grateful for their support of this discipleship initiative in the Evangelical Covenant Church of Canada. www.trellisfoundation.ca This Lenten Reader is a gift to the Church and therefore may be used free of charge. All artwork is referenced in the Bibliography. Please give credit where due when reproducing or quoting from the Lenten Reader. © 2018 Evangelical Covenant Church of Canada Winnipeg, Manitoba Editors: Julia Sandstrom & Hanne Johnson A Brief Introduction to Lent My dad is a master toy maker. He has made chickens, grasshoppers, ducks, bulldozers, dump trucks, ferry boats, cars, trains, and more for his grandkids. He is currently adding train cars to our family’s collec- tion. My sister and I each get a set of toys for our kids, but each new grandchild’s first toy is for them specifically. It’s the first in the collec- tion and it’s my favourite treasure: the baby rattle. Due to a long distance move and shoulder surgery, my daughter didn’t receive her rattle until this last month at nearly 10 months old. It was worth the wait though, because for the first time I got to watch my dad turn a rattle on his lathe. -

Party Tunes Dj Service Artist Title 112 Dance with Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream

Party Tunes Dj Service www.partytunesdjservice.com Artist Title 112 Dance With Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream 112 Peaches & Cream (feat. P. Diddy) 112 U Already Know 213 Groupie Love 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Creatures 311 It's Alright [Album Version] 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe 702 Steelo [Album Edit] $th Ave Jones Fallin' (r)/M/A/R/R/S Pump Up the Volume (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ame iro Rondo (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Chance Chase Classroom (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Creme Brule no Tsukurikata (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Duty of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Eyecatch (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Great escape (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Happy Monday (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Hey! You are lucky girl (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kanchigai Hour (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kaze wo Kiite (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ki Me Ze Fi Fu (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kitchen In The Dark (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kotori no Etude (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Lost my pieces (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari love on the balloon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Magic of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Monochrome set (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Morning Glory (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Next Mission (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Onna no Ko no Kimochi (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Psychocandy (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari READY STEADY GO! (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Small Heaven (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Sora iro no Houkago (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Startup (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tears of dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tiger VS Dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Todoka nai Tegami (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yasashisa no Ashioto (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yuugure no Yakusoku (ToraDora!) Horie Yui Vanilla Salt (TV-SIZE) (ToraDora!) Kugimiya Rie, Kitamura Eri & Horie Yui Pre-Parade (TV-SIZE) .38 Special Hold on Loosely 1 Giant Leap f. -

Kevin Max "Run on for a Long Time" Featuring Chris Sligh from American Idol!

411 SPECIAL REPORT dio Alliance Updates PLUS Charter - I Focus On Local Initiatives Meet HD Radio's first' ONLINE: 'AV ROOM' OFFERS VIDEO VERSION OF 99X/ATLANTA .uCR 11... P L - 1.1 r-111. ADAM CAROLLA OUTLASTS PREPPING PERSONALITIES OTHER STERN RE3LACEMENTS OR THE PPM COMMUNITY SERVICE;. KEZE/ ow rogrammers re He ping SPOKANE'S DJ MAYHEM GIVES BACK Air Talent Adapt To Electronic RADIO & RECORDS CCNSUMERS 'AWAKEN' Audience Measurement p.14 WITH CARE FOR ALL THINGS GREEN NOVEMBER 23, 2007 NO. 1737 $6.50 www.F:adican=Rrcords.com /DVERTIS M=NT Kevin Max "Run On For A Long Time" Featuring Chris Sligh from American Idol! And COMING in Early 2008: Kevin Max, Michael Tait and Toby Mac return. to radia with a HUGE SMASH HIT "The Cross"!!! NEW ALBUM: The Blood Available December 26 2007 featuring such heavyweights as DC Talk (together for t-le first time since solo career began), Amy Grant, Vince Gill, Chris Sligh (American [dol), Mary Mary and others!! MM. "To JILL Bring PAPP You `Reach" Back" was one THE of the INCREDIBLE NEW SINGLE most FROM sought out songs Paul Alan of 2007. 'OI NG FOR ADDS NOW!! The winding road leads to "'Incredible' is just one of the many ords to describe the song. It is more than .Me gain Jan. 2008 consideration for me. I don't know how I CAN'T add it." -Mike Schlote, KZZQ PROMO CONTACT: SHAMROCK MEDIA GROLIF. CHRIS [email protected] or 615.4E 3.8247 www.americanradiohistory.com NOW at RiIDIO Play MPETM incorporates the following features: A "Go Green" environmental source for delivery Automation and Scheduling Integration Player and Direct web access Playerless Download* Cover Art and Info iPod and WMA Music Videos CD Burning HD Audio PC & Mac Playlists Coming January 2008 Contact your label representatives and request that music be delivered to you via Play MPE. -

September 2002, Vol

Today Is the Day of Evangelism oday is the day of evangelism. Today, My daughter, Celeste, and I were on a like no other day, is the day of family plane that was tossed like a rag doll in the Tevangelism. These two words are fierce, deadly winds of Hurricane Floyd. I rarely said in the same sentence. However, was on a plane that caught fire. My hus- fear of sharing Jesus with our loved ones band, Edwin, and I were returning from is, for many, like a fire-breathing dragon Florida when the pilot said, “We’ll need to that needs to be slain. make an emergency landing. There’s a crack Here’s how to slay the dragon. Think of in the windshield.” God’s protection is part family evangelism as a lifetime mega oppor- of His love toward us, and love draws. tunity to share. That’s it. Convincing anoth- I watched in amazement as our second Fear of sharing er of the truth is the Holy Spirit’s work; so son, Edwin (LeNe), exploded with confi- simply share your experiences and give dence in the face of rejection. As a recent Jesus with our God the praise. Since heaven would not be graduate from Andrews University he sub- grand or glorious without my family, I mitted his application to RIT only to loved ones is, evangelize them by sharing Christ whether receive a disappointing no. LeNe has been on the housetop or in the garden. evangelized all his life. He prayed to His for many, like My elder son, Donald, was diagnosed heavenly Father and then wrote the with hypertrophy cardiomyopathy almost department chairperson a compelling let- a fire-breathing two years ago. -

Reading Revelation 21-22 Julie M

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Maxwell Institute Publications 2016 Apocalypse: Reading Revelation 21-22 Julie M. Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi Part of the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Julie M., "Apocalypse: Reading Revelation 21-22" (2016). Maxwell Institute Publications. 10. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/mi/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maxwell Institute Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Introduction Julie M. Smith In what would become the standard explanation of how parables work, biblical scholar C. H. Dodd proclaimed that the parable “arrest[s] the hearer by its vividness of strangeness, and leave[s] the mind in sufcient doubt about its precise application to tease it into active thought.”1 What is true of parables is doubly, if not triply, true of the book of Revelation. Two millennia have apparently not been enough for a consensus to emerge regarding the interpretation of this enigmatic text. Why is that? The book itself gives us two clues in its very rst verse, where John describes the text and how it came to be. First, he calls it an apokalypsis (see Revelation 1:1). We recognize the English cognate apocalypse and think, perhaps, of big-budget disaster movies, but the Greek word has a different nuance: it means “uncovering.” The author thus describes his task in writing as one of uncovering truth for the reader, but what truths does he intend to uncover, and how are they to be uncovered? These questions bring us to our second clue: as the Revelator describes the process by which the revelation was transmitted, he explains that it was “signied” by an angel (Revelation 1:1). -

Jeanne Severance Letters, 1945-1946 SC2014.014

Jeanne Severance Letters, 1945-1946 SC2014.014 Transcribed by Rosemary Heher, April-July 2018 Salisbury University Nabb Research Center Special Collections Preferred citation: Item, collection name, [Box #, Folder #,] Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture, Salisbury University, Salisbury, Maryland. ENVELOPE VIA AIR MAIL (Sender) PAULINE DOLL ARC CLUBMOBILE GP “H” APO 340 c/o Postmaster New York NY (Addressee) Miss Connie Greene Easthampton Long Island, New York (Postmark) PASSED BY US ARMY EXAMINER BASE 1587 (Postmark) US Army Postal Service A.P.O 340 JAN 2 1945 CORRESPONDENCE January 2, 1945 HAPPY NEW YEAR FROM NOT SO SUNNY FRANCE – (in fact it’s a very frost bitten France these days) Hi there Connie ya rat: Hit the jack-pot when the old green(e) came through with that wonderful pk. No kidding Connie what a nice person you are to remember me. Thanks a lot. Just had to turn out the light, for my blackout taint so good and there is a little excitement at the present. Am writing this via candle, but am used to that by now. Have two great bits of news to tell you. The greatest thing first, and that is, by the time you get this letter, I will be Mrs. William Savage, that is if Jerry will let us have our forty-eight hours on January 18th. “Flip” is a Lt. in the F.A. and comes from Richmond, Va. He is only six five in his stocking feet and I just come under his arm. He sent over to the states for our rings, and if you look, you will see the sparkle of my diamond on the print of this letter. -

Island of Abundance

Island of Abundance Return of the Phoi Raja’s eyes fluttered open, as he was drawn out of his slumber by the sound of a crackling fire. The sun was just peaking above the horizon, and Raja could see a large, blurred silhouette in front of him, hunching over the flames. Lifting himself onto his elbow, he strained to see clearer who this visitor was. “Awake I see! Best way for you to be!” Resio’s jovial rhyme floated on the crisp morning air. “Yes. Hello, Resio.” Hearing the bear’s familiar voice, Raja visibly relaxed. “It’s good to see you again.” “Indeed, indeed. I came to lead!” Resio rose up to his full, enormous stature, and he lumbered over to Raja’s side. Raja grinned, lowering his eyes. “To lead, huh?” He paused, then squinted up into Resio’s gaze. “I seem to recall that, the last time you led, I found myself hanging onto your stump of a tail for dear life!” “Yes, I too remember that trip! And, yes, I too recall your grip!” Resio’s fur involuntarily quivered, as if shaking off a bad experience, while his body quaked with laughter. After a moment, he grew quiet; and, dropping to all fours, he lowered his face near to Raja’s. “It is time, my friend,” he softly growled. “Your journey on Resilience is at an end. Arise, arise, and you shall see--Abundance beckons steadily.” With his smile fading to curiosity, Raja stood, shooting a glance at Syndi and Liam, who were both still sleeping soundly. -

Miracles Manual Final.Pdf

© 2013 by Hypnotic Marketing, Inc. © 2013 by Hypnotic Marketing, Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution are forbidden. No part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any other means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information with regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the author and the publisher are not engaged in rendering legal, intellectual property, accounting, or other professional advice. If legal advice or other professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought. Dr. Joe Vitale and Hypnotic Marketing, Inc. individually or corporately, do not accept any responsibility for any liabilities resulting from the actions of any parties involved. www.miraclescoaching.com 2 © 2013 by Hypnotic Marketing, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction Secret Session #1 Secret Session #2 Secret Session #3 Secret Session #4 Secret Session #5 Secret Session #6 Secret Session #7 Secret Session #8 Secret Session #9 Secret Session #10 Secret Session #11 Secret Session #12 www.miraclescoaching.com 3 © 2013 by Hypnotic Marketing, Inc. Expect Miracles! An Introduction by Dr. Joe Vitale For more than four years now I have been answering questions from students in my famous Miracles Coaching™ program. They've asked everything from – * How do I stay positive when people around me are negative? * How do I discover my life purpose when I don't know what I want? * How do I attract money in this terrible economy? * How do I attract my soulmate? * How do I improve my self-image? * How do I help others? * What can I do when everything looks hopeless? Those questions – and hundreds of others – have been asked every month for years.