An Interview with Bobby Unser an Interview with Bobby Knight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Indy Stars Revere the Salt

Many Indy Stars Revere The Salt Astonishingly, until this year, I had awhile and get your lakester running! other car was a rear engine. racing luck with mixed results. never covered “the greatest spectacle”, End personal segue. Reaching way back, we find my all- Indy Ace Tony Bettenhausen drove aka the Indy 500. As a veteran motor- Let’s start with names that most LSR time land speed racing hero, Frank on the salt in 1955 setting 18 Internation- sports journalist, my brain would have folks know, but may not realize they had Lockhart who, at the 1926 Indianapolis al Records in the F Class (1.500 cc) exploded to just be a spectator, so I put ties to Indiana oval. Those people that 500, was a relief driver for Peter Kreis’s records in an OSCA sports car with together a little track lapping activity. have a year and speed in parentheses indi- eight cylinder supercharged Miller. He c-driver Marshall Lewis. The idea was for land speed, drag, jet cates Bonneville 200MPH Club won the race becoming the fourth rookie Among other Indy racers who also and rocket racer Paula Murphy, aka “Miss membership. ever to do so. Lockhart, you will remem- drove on the salt you’ll find such names STP” to reprise her milestone role as the For instance, cheerful and always ber, together with the Stutz Automobile as: Dan Gurney, Rex Mays, Jack McGrath, first woman ever allowed to drive a race charming Leroy Newmayer (1953 Company, broke World Land Speed Cliff Bergere, Wilbur D’Alene, Bud Rose, car upon the venerable brickyard oval. -

Spotter Guide

FAST FACT During the tire building process, heat and pressure are applied to form the tire in a process known as vulcanizing. This transformation process is named after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire. Here in Birmingham, there is a 56-foot statue of Vulcan that overlooks downtown from Red Mountain. Confetti flies in Victory Lane following the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach as podium finishers (and Penske teammates) Juan Pablo Montoya and Helio Castroneves celebrate with winner Scott Dixon. Chris Owens/IMS Photo WHAT TO WATCH FOR THIS WEEKEND: DIXIE DOES IT: Scott Dixon (right) had just one top- five finish in eight starts at Long Beach entering last weekend’s race, but when the checkered flag flew on Sunday he came away a victor, earning his 36th overall race win and breaking a tie for fifth with Bobby Unser on the all-time Indy car wins list. Can Dixon carry the winning momentum from the West Coast to Barber Motorsports Park? PENSKE LOOKS TO CONTINUE BARBER DOMINATION: Team Penske has won three of the previous five Verizon IndyCar Series races at Barber Motorsports Park and team owner Roger Penske will look to add another trophy to his team’s collection during the Honda Indy Grand Prix of Alabama with a strong four- car stable that has been dominant through the first three races of the season. HUNTER-REAY GOES FOR ALABAMA HAT TRICK: Andretti Autosport’s Ryan Hunter-Reay is the only driver to keep Team Penske out of victory lane at Barber Motorsports Park with his back-to-back wins at the track in 2013 and 2014. -

500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More!

BOOMER Indy For the best years of your life NEW! BOOMER+ Section Pull-Out for Boomers their helping parents 500 Miles + 100 Years = Many Race Memories Bobby Unser • Janet Guthrie • Donald Davidson • Bob Jenkins and More! Women of the 500 Helping Hands of Freedom Free Summer Concerts MAY / JUNE 2016 IndyBoomer.com There’s more to Unique Home Solutions than just Windows and Doors! Watch for Unique Home Safety on Boomer TV Sundays at 10:30am WISH-TV Ch. 8 • 50% of ALL accidents happen in the home • $40,000+ is average cost of Assisted Living • 1 in every 3 seniors fall each year HANDYMAN TEAM: For all of those little odd jobs on your “Honey Do” list such as installation of pull down staircases, repair screens, clean decks, hang mirrors and pictures, etc. HOME SAFETY DIVISION: Certified Aging in Place Specialists (CAPS) and employee install crews offer quality products and 30+ years of A+ rated customer service. A variety of safe and decorative options are available to help prevent falls and help you stay in your home longer! Local Office Walk-in tubs and tub-to-shower conversions Slip resistant flooring Multi-functional accessory grab bars Higher-rise toilets Ramps/railings Lever faucets/lever door handles A free visit will help you discover fall-hazards and learn about safety options to maintain your independence. Whether you need a picture hung or a total bathroom remodel, Call today for a FREE assessment! Monthy specials 317-216-0932 | geico.com/indianapolis for 55+ and Penny Stamps, CNA Veterans Home Safety Division Coordinator & Certified Aging in Place Specialist C: 317-800-4689 • P: 317.337.9334 • [email protected] 3837 N. -

The Indy Racing League and the Indianapolis 500

The Indy Racing League and the Indianapolis 500: Increasing Competition in Open-Wheeled Automobile Racing in the United States Robert W. White Department of Sociology and Andrew J. Baker Department of Geography School of Liberal Arts IUPUI We thank Terri Talbert-Hatch and Pete Hylton for their comments and support of Motorsports Studies. Please direct correspondence to Robert White ([email protected]), Professor of Sociology and Director of Motorsports Studies, or Andrew Baker ([email protected]), Lecturer, Department of Geography, School of Liberal Arts, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), 425 University Boulevard, Indianapolis, Indiana, 46202. 1 The Indy Racing League and the Indianapolis 500: Increasing Competition in Open-Wheeled Automobile Racing in the United States Abstract Over the course of its lengthy history, the popularity of open-wheeled automobile racing in the United States has waxed and waned. This is especially evident in recent years. The 1996 “split” between the Indy Racing League (IRL; later, the IndyCar Series) and Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART; later the Champ Car World Series) severely hurt the sport. Following the split there was a well-documented decline in fan interest from which the sport has not recovered. Less understood, however, is that under the Indy Racing League the Indianapolis 500, the premier event in open-wheeled racing in the United States, became more competitive. Ironically, while fan interest decreased in the Indy Racing League era, the quality of racing increased. The increased competition associated with the Indy Racing League is a historically significant development that bodes well for the future of the sport. -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

INDYCAR Grand Prix for the Second Time in His Career on May 13, Will Power of Team Penske Aims to Make History at Indianapolis

POWER TRIES FOR INDIANAPOLIS SWEEP - After winning the INDYCAR Grand Prix for the second time in his career on May 13, Will Power of Team Penske aims to make history at Indianapolis. Power could become the fi rst Verizon IndyCar Series driver to win on both the IMS Road Course and Oval. Can Power complete a history-making Month of May? Joe Skibinski/INDYCAR PHOTO WHAT TO WATCH FOR THIS WEEKEND: WILL HELIO WIN FOURTH INDY 500?: Three-time Indianapolis 500 winner Helio Castroneves can join elite company should he win the Indianapolis 500-Mile Race. Castroneves, who won in 2001, 2002 and 2009, would join A.J. Foyt, Al Unser and Rick Mears as the race’s only four-time winners. FORMER CHAMPIONS RETURN IN SEARCH OF SECOND WIN: Five former Indianapolis 500 winners return with eyes on adding a second Baby Borg to their collection. 2008 winner Scott Dixon and 2013 winner Tony Kanaan return with the formidable Chip Ganassi Racing team. Ryan Hunter-Reay and reigning champion Alexander Rossi will aim to bring Andretti Autosport another win in the Indy 500 and Buddy Lazier returns with Lazier-Burns Racing 20 years after claiming his Indy 500 win. Can a former winner score a second Indianapolis win? FROM THE POLE TO VICTORY LANE: The winner of the pole position for the Indianapolis 500 has also won the race 20 times. Forty-three times, the winner has come from the front row, the last time in 2010 with Dario Franchitti. Who can establish themselves as a race contender by winning the pole position or qualifying on the front row this year? PENSKE SEEKS HISTORY: Team owner Roger Penske has won the Indianapolis 500 a record 16 times and brings five strong entries in 2017 with three-time Indianapolis 500 winner Helio Castroneves, two-time Indianapolis 500 winner Juan Pablo Montoya, series points leader Simon Pagenaud, former Verizon IndyCar Series champion Will Power and rising star Josef Newgarden. -

Investigation Into the Provenance of the Chassis Owned by Bruce Linsmeyer

Investigation into the provenance of the chassis owned by Bruce Linsmeyer Conducted by Michael Oliver November 2011-August 2012 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Design, build and development .............................................................................................................. 6 The month of May ................................................................................................................................ 11 Lotus 56/1 - Qualifying ...................................................................................................................... 12 56/3 and 56/4 - Qualifying ................................................................................................................ 13 The 1968 Indy 500 Race ........................................................................................................................ 14 Lotus 56/1 – Race-day livery ............................................................................................................ -

Official Rule Book Table768b of Contents

2016 VERIZON INDYCAR SERIES OFFICIAL RULE BOOK TABLE768B OF CONTENTS 631B GENERAL ................................................................ 7 GOVERNANCE .......................................................... 7 SAFETY ................................................................. 12 LOGO DISPLAY ....................................................... 21 ADVERTISING ......................................................... 21 TITLE SPONSOR ...................................................... 22 PRODUCT USE ........................................................ 24 MEMBERSHIP ........................................................ 31 GENERAL .............................................................. 31 APPLICATION ......................................................... 31 TERM ................................................................... 33 INTERIM REVIEW OF QUALIFICATIONS ......................... 33 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF RELEASE AND ASSUMPTION OF RISK ................................................................ 33 APPLICABLE LAWS AND JURISDICTION ......................... 33 CONDUCT IDENTIFICATION ........................................ 35 LITIGATION ............................................................ 35 CATEGORIES .......................................................... 35 AGE ................................................................... 36 MORAL FITNESS ................................................... 36 PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL FITNESS .................... 37 MEDICAL EXAMINATIONS -

Happy 75Th Birthday to Legendary Driver Mario Andretti! BRUCE MARTIN / FOX SPORTS FOXSPORTS.COM

Happy 75th birthday to legendary driver Mario Andretti! BRUCE MARTIN / FOX SPORTS FOXSPORTS.COM FEB 28, 2015 4:53p ET Jonathan Ferrey / Getty Images Mario Andretti has dominated in nearly every form of racing, making him one of the most iconic drivers of all time. As Mario Andretti celebrates his 75th birthday on Feb. 28, one of the most magical names in international racing history chooses not to pause and reflect on his extraordinary accomplishments or his remarkable life. He doesn't think back to the long days when he grew up in a displaced persons camp in what is now Croatia from the darkest days Europe ever experienced during World War II. That is when Andretti's native Italy was under siege as a member of the Axis powers during the war. During the Istrian exodus of 1948, Andretti's family was confined to an internment camp in Lucca, Italy, along with other families trying to flee communism in post-World War II Europe. But there is one day that Andretti will remember on this milestone birthday, and it came on June 16, 1955. The ocean liner carrying Luigi and Rina Andretti's family cruised into New York Harbor, and the 15-year-old Mario saw the Statue of Liberty gleaming like a beacon of hope at dawn of a glorious summer day. "That was one memorable morning," Andretti told FOXSports.com from his home in Nazareth, Pennsylvania. "It was June 16, 1955, at 5 a.m. We were sailing past the Statue of Liberty on a beautiful, radiant morning, and we were celebrating my sister Ana Maria's 21st birthday. -

Scott Dixon Historical Record Sheet During Current Win Streak

Most Seasons With At Least One Win (1946-2014) Seasons Driver Sanctioning Organization 18 A.J. Foyt USAC 16 Mario Andretti USAC, CART 15 Michael Andretti CART 14 Al Unser USAC, CART Al Unser Jr. CART, IRL Bobby Unser USAC, CART Helio Castroneves CART, IRL, IC 13 Rick Mears USAC, CART Gordon Johncock USAC, CART 12 Johnny Rutherford USAC, CART Scott Dixon CART, IRL, IC 11 Emerson Fittipaldi CART Paul Tracy CART, CC Dario Franchitti CART, IRL, IC 10 Bobby Rahal CART Tony Kanaan CART, IRL, IC 8 Scott Sharp IRL Rodger Ward USAC Danny Sullivan CART, USAC Ryan Hunter-Reay CART, CC, IRL, IC Will Power CC, IRL, IC 7 Gil de Ferran CART, IRL Sam Hornish, Jr. IRL Tom Sneva CART, USAC 6 Justin Wilson CC,IRL, IC Sebastien Bourdais CC, IC Most Consecutive Seasons With One or More Wins (1946-2014) Seasons Driver Years Sanctioning Organization 11 Bobby Unser 1966-1976 USAC Emerson Fittipaldi 1985-1995 CART Helio Castroneves 2000-2010 CART, IRL 10 Scott Dixon 2005-2014 IRL, IC 9 Johnny Rutherford 1973-1981 USAC Michael Andretti 1994-2002 CART 8 Rick Mears 1978-1985 USAC, CART Bobby Rahal 1982-1989 CART Al Unser Jr. 1988-1995 CART 7 Rodger Ward 1957-1963 USAC Gordon Johncock 1973-1979 USAC, CART Scott Sharp 1996/97-2003 IRL Sam Hornish Jr. 2001-2007 IRL 6 Tony Kanaan 2003-2008 IRL Scott Dixon’s Year-By-Year during current win streak (2005-2014) Year Total Wins Races Won Sanctioning Organization 2005 1 Watkins Glen IRL 2006 2 Watkins Glen IRL Nashville 2007 4 Watkins Glen IRL Nashville Mid-Ohio Sonoma 2008 6 Homestead-Miami IRL (**) Indianapolis Texas Nashville Edmonton Kentucky 2009 5 Kansas IRL Milwaukee Richmond Mid-Ohio Twin Ring Motegi (oval) 2010 3 Kansas IRL Edmonton Homestead-Miami 2011 2 Mid-Ohio INDYCAR Twin Ring Motegi (road) 2012 2 Detroit-Belle Isle INDYCAR Mid-Ohio 2013 4 Pocono INDYCAR (**) Toronto (Race 1) Toronto (Race 2) Houston (Race 1) 2014 2 Mid-Ohio INDYCAR Sonoma ** Season Champion in 2008 & 2013 . -

IMS Museum Honoring Andretti's Legendary Career with Exhibit

IMS Museum honoring Andretti's legendary career with exhibit March 6, 2019 – The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum will honor 1969 Indianapolis 500 winner Mario Andretti and his illustrious racing career with the exhibit, “Mario Andretti: ICON,” presented by Shell V-Power NiTRO+, opening to the public Wednesday, May 1. The exhibit is part of a comprehensive 50th anniversary celebration of Andretti’s victory at the Indianapolis 500. Andretti led 116 laps and delivered a popular, long-awaited victory for colorful car owner Andy Andretti with 1969 Indy 500 Granatelli, despite having to race in a backup car, battling race-long winning Brawner Hawk engine overheating issues and being forced to run all 500 miles on the same right-rear Firestone tire. “Mario Andretti: ICON,” presented by Shell V-Power NiTRO+, will bring together many of the most significant cars in Andretti’s career at the IMS Museum – cars which also represent significant milestones in motorsports history given Andretti’s accomplishments. The featured exhibits of “Mario Andretti: ICON,” are a full representation of the Nazareth, Pennsylvania, resident’s diverse career. A sampling of this can’t-miss exhibit includes: • The John Player Special Lotus Type 79-4, from the 1978 Formula One World Championship run • The 1974 Vel’s Parnelli Jones team Formula One car • 1967 Dean Van Lines Brawner Hawk II Indy 500 pole-winner • 1967 Watson Leader Card Sprint car • The 1967 Daytona 500-winning car • A 1994 Lola T9400 from his “Arrivederci Mario” farewell season • The Horn Offenhauser Sprint car, named “Baby,” from Andretti’s first Sprint car race. -

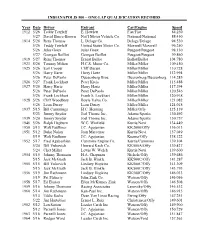

One Lap Record

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ONE-LAP QUALIFICATION RECORDS Year Date Driver Entrant Car/Engine Speed 1912 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff E. Hewlett Fiat/Fiat 84.250 5/27 David Bruce-Brown Nat’l Motor Vehicle Co. National/National 88.450 1914 5/26 Rene Thomas L. Delage Co. Delage/Delage 94.530 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff United States Motor Co. Maxwell/Maxwell 96.250 5/26 Jules Goux Jules Goux Peugeot/Peugeot 98.130 5/27 Georges Boillot Georges Boillot Peugeot/Peugeot 99.860 1919 5/27 Rene Thomas Ernest Ballot Ballot/Ballot 104.780 1923 5/26 Tommy Milton H.C.S. Motor Co. Miller/Miller 109.450 1925 5/26 Earl Cooper Cliff Durant Miller/Miller 110.728 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 112.994 5/26 Peter DePaolo Duesenberg Bros. Duesenberg/Duesenberg 114.285 1926 5/27 Frank Lockhart Peter Kreis Miller/Miller 115.488 1927 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 117.294 5/26 Peter DePaolo Peter DePaolo Miller/Miller 120.546 5/26 Frank Lockhart Frank S. Lockhart Miller/Miller 120.918 1928 5/26 Cliff Woodbury Boyle Valve Co. Miller/Miller 121.082 5/26 Leon Duray Leon Duray Miller/Miller 124.018 1937 5/15 Bill Cummings H.C. Henning Miller/Offy 125.139 5/23 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.492 1939 5/20 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.757 1946 5/26 Ralph Hepburn W.C. Winfield Kurtis/Novi 134.449 1950 5/13 Walt Faulkner J.C. Agajanian KK2000/Offy 136.013 1951 5/12 Duke Nalon Jean Marcenac Kurtis/Novi 137.049 5/19 Walt Faulkner J.C.