Gus Visser and His Singing Duck by Scott Simmon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Words: the Birth of Sound Cinema

First Words The Birth of Sound Cinema, 1895 – 1929 Wednesday, September 23, 2010 Northwest Film Forum Co-Presented by The Sprocket Society Seattle, WA www.sprocketsociety.org Origins “In the year 1887, the idea occurred to me that it was possible to devise an instrument which should do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear, and that by a combination of the two all motion and sound could be recorded and reproduced simultaneously. …I believe that in coming years by my own work and that of…others who will doubtlessly enter the field that grand opera can be given at the Metropolitan Opera House at New York [and then shown] without any material change from the original, and with artists and musicians long since dead.” Thomas Edison Foreword to History of the Kinetograph, Kinetoscope and Kineto-Phonograph (1894) by WK.L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson. “My intention is to have such a happy combination of electricity and photography that a man can sit in his own parlor and see reproduced on a screen the forms of the players in an opera produced on a distant stage, and, as he sees their movements, he will hear the sound of their voices as they talk or sing or laugh... [B]efore long it will be possible to apply this system to prize fights and boxing exhibitions. The whole scene with the comments of the spectators, the talk of the seconds, the noise of the blows, and so on will be faithfully transferred.” Thomas Edison Remarks at the private demonstration of the (silent) Kinetoscope prototype The Federation of Women’s Clubs, May 20, 1891 This Evening’s Film Selections All films in this program were originally shot on 35mm, but are shown tonight from 16mm duplicate prints. -

L'audiovision Dans Le Cinéma D'animation

L’audiovision dans le cinéma d’animation : contribution à la sémiotique Juan Alberto Conde Aldana To cite this version: Juan Alberto Conde Aldana. L’audiovision dans le cinéma d’animation : contribution à la sémiotique. Linguistique. Université de Limoges, 2016. Français. NNT : 2016LIMO0094. tel-01877580 HAL Id: tel-01877580 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01877580 Submitted on 20 Sep 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE LIMOGES ECOLE DOCTORALE n° 527 : « Cognition, Comportement, Langage(s) » Centre de Recherches Sémiotiques (CeReS) Thèse pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE LIMOGES Sciences du langage, spécialité sémiotique Présentée et soutenue par Juan Alberto CONDE Thèse de doctorat doctorat Thèse de Le 16/12/2016 L’audiovision dans le cinéma d’animation expérimental Approche sémiotique Thèse dirigée par Jacques FONTANILLE JURY : Rapporteurs M. François Jost, Professeur émérite de l’Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris 3), Directeur Honoraire du CEISME M. Laurent Jullier, Professeur à l’Université de Lorraine, IECA, (Nancy) Examinateurs M. Anne Beyaert, Professeur des Universités Université Montaigne à Bordeaux, Directrice du MICA, MSHA M. Jacques Fontanille, Professeur émérite, Université de Limoges, CeReS M. -

ELECTRONICS PIONEER Lee De Forest

ELECTRONICS PIONEER Lee De Forest by I. E. Levine author of MIRACLE MAN OF PRINTING: Ottmar M1ergenthaler, etc. In 1913 the U. S. Government indicted a scientist on charges that could have sent him to prison for a decade. An angry prosecutor branded the defendant a charlatan, and accused him of defrauding the public by selling stock to manufacture a worthless device. Fortunately for the future of electronics - and for the dignity of justice - the defendant was found innocent. He was the brilliant inventor. Lee De Forest, and the so-called worthless device was a triode vacuum tube called an Audion; the most valuable discovery in the history of electronics. From his father, a minister and college president, young De Forest acquired a strength of character and purpose that helped him work his way through Yale and left him undismayed by early failures. Ilis first successful invention was a wireless receiver far superior to Marconi's. Soon he devised a revolutionary trans- mitter, and at thirty was manufacturing his own equip- ment. Then his success was wiped out by an unscrup- ulous financier. De Forest started all over again, per- fected his priceless Audion tube and paved the way for radio broadcasting in America. Time and again it was only De Forest's faith that helped him surmount the obstacles and indignities thrust upon him by others. Greedy men and powerful corporations took his money, infringed on his patents and secured rights to his inventions for only a fraction of their true worth. Yet nothing crushed his spirit or blurred his scientific vision. -

EL PATRIMONIO SONORO01.Pdf

Laura Prieto Radio Nacional de España Universidad Complutense de Madrid Bogotá, Noviembre 2014 EL PATRIMONIO SONORO EN EL CONTEXTO DEL PATRIMONIO AUDIOVISUAL JORNADAS ACADÉMICAS SOBRE TÉCNICA Y GESTIÓN EN LOS ARCHIVOS AUDIOVISUALES Orígenes de la comunicación Interés del hombre por comunicarse con sus semejantes Nacimiento del lenguaje: 250.000 años Homo Sapiens Martin Heidegger: el lenguaje es la casa del ser, donde mora la esencia humana Neardental: aparato fonador capacitado para emitir fonemas y darles un carácter simbólico. Comunicación oral. Elementos pictóricos. Escritura Nacimiento de la Música vinculado al nacimiento del lenguaje Música: intencionalidad de hablar con una entonación, altura y expresión particulares Lenguaje y Música: objetivo común = comunicación Patrimonio sonoro Elementos ligados a la existencia de soportes para convertirse en realidad Soporte = 2 perspectivas sustancia inerte que en un proceso proporciona la adecuada superficie de contacto o fija alguno de sus reactivos (cualidad física) material en cuya superficie se registra información = elemento de las telecomunicaciones (cualidad intelectual) Soportes = esencia del patrimonio Sonido Palabra Música Efectos sonoros Sintonías, indicativos, ráfagas… Anuncios y cuñas publicitarias Objetivos: Intrínsecos Creativo Documental Elaboración de programas Extrínsecos Copia judicial Investigación Colaboración con instituciones políticas o judiciales Comercialización y difusión directa Palabra Característica: presencia voz humana Objetivos: -

Auburnpub.Com 2 Thursday, June 10, 2010 Founders Day the Citizen

auburnp ub. com 2 Thursday, June 10, 2010 Founders Day The Citizen. Auburn, New York Museum hopes Case’s star will shine Auburnian who made film history is focus of fundraiser CHRISTOPHER CASKEY And officials with film history. the museum. The Auburn native The Citizen the local museum in The Cayuga “Our biggest hope pioneered a system to charge of preserving Museum will host a ... is to just raise put sound onto film in Theodore W. Case Case’s legacy hope the special fundraiser that awareness of what Ted the early 20th century, will be on center stage event and its high- day, with Founders Case did and what his and he used the June 12 when the city profile guests help Day guest and Oscar- work was,” said Lauren carriage house on the of Auburn holds the spread the word about nominated actress Chyle, curator for the same property to second-annual the late Auburn inven- Sigourney Weaver on Cayuga Museum. “We record films with Founders Day. tor’s contribution to hand for the recep- take very seriously our sound. tion. stewardship of this The Cayuga Inside Founders Day The museum will collection.” Museum maintains also be open all day That collection archives of Case’s Case’s star will shine ...................................Pg. 2-3 Life of Theodore Case .......................................Pg.4 for visitors and people includes the research research and Carriage House Theatre ...................................Pg.5 will be able to take laboratory and back- correspondences and Map ...............................................................Pg. 6 guided tours of the yard movie studio the museum oversees Sigourney Weaver .......................................Pg. -

P-74 Film Frame Collection

P-74 Film Frame Collection Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1889 – 1947, undated (bulk 1900 – 1933, undated) Extent: 5.8 linear feet Language: English Abstract: Specimens of motion picture film compiled and catalogued by Earl Theisen (1903-1973). A portion of the collection is derived from other motion picture history donations to the museum, but most of the items were collected by the donor. Biographical Note: Theisen (1903-1973) was the Honorary Curator of Motion Picture and Theatrical Arts at the then-called Los Angeles Museum for several years following 1931. He had a primary role at the museum in developing the Motion Picture Gallery. Much of the film collections in the museum’s History Department were acquired as a result of his efforts. He was a technician at the Dunning Process Plant, a member of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, and a member of the Society’s Historical Committee. He wrote articles for the publication “The International Photographer” from about 1932 to 1936 and also served as its Associate Editor. In articles he discussed the history of motion pictures; film production and the film industry, including the art of animation; in a semi- regular column he covered news about the Hollywood industry. One of the articles from the May, 1934 issue noted that he was a “member of the Faculty as Lecturer in the Department of Cinematography, University of Southern California.” While serving as curator at the museum, Theisen became active as the Executive Secretary of the Motion Picture Hall of Fame at the California-Pacific International Exposition (1935-1936) at San Diego, California. -

Talking Pictures Origins of Sound Cinema 1913 – 1929

Talking Pictures Origins of Sound Cinema 1913 – 1929 Tuesday, August 21, 2018 Grand Illusion Cinema The Sprocket Society Seattle, WA This Evening’s Film Selections All films in this program were originally shot on 35mm, but are shown tonight from 16mm prints that are a mix of originals, reductions, and dupes. All soundtracks are from the original recordings as released, but they have obviously been converted to modern optical sound film technology. Sound quality and volume will vary, reflecting not only the original technologies, but also in some cases the decay of the source elements prior to preservation. A different program with a similar selection of films was presented previously by The Sprocket Society, in September 2010 at the Northwest Film Forum. The program notes for that are available on our web site. Nursery Favorites (American Talking Picture Co. [Edison/Keith-Albee], May 1913) 9 min. Edison Kinetophone sound-on-cylinder Directed by Allen Ramsey, photographed by Joe Physiog. With Edna Flugrath, Robert Lett, Shirley Mason, Robert Milasch as the giant, and the Edison Players Quartette Orchestra. One of the few surviving examples of Edison Today, what’s known to survive is only 12 of the Kinetophone films, which synchronized an films (mainly held at the Library of Congress) and oversized cylinder phonograph with a modified 15 of the soundtrack recordings (in the archives of 35mm projector via a very long loop of linen cord the Thomas Edison National Historic Park). Of soaked in castor oil. The system had severe these, just eight are matching pairs. By 2016, the operational and sound quality problems, and lasted Library of Congress completed digitally restoration only about a year. -

ARSC Journal, Spring 1991 35 Operatic Vitaphone Shorts

THE OPERATIC VITAPHONE SHORTS By William Shaman On 6 August 1926 "Vitaphone," the latest commercial sound-on-disc motion picture system, made its debut at the Warners' Theater in New York City. The feature film that evening, "Don Juan," with John Barrymore and Mary Astor, was a lavish costume picture with a pre-recorded soundtrack consisting of synchronized sound effects and a Spanish-flavored score written by Major Edward Bowes, David Mendoza, and Dr. William Axt, played by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra under Henry Hadley. There was no spoken dialogue. Eight short subjects preceded "Don Juan:" Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers Association, welcoming the Vitaphone in a spoken address; the Overture to Tannhauser played by the New York Philharmonic, again with Hadley conducting; violinist Mischa Elman, accompanied by pianist Josef Bonime, playing Dvorak's "Humoresque" and Gossec's "Gavotte;" Roy Smeck, "Wizard of the Strings," in a medley of Hawaiian guitar, ukulele, and banjo solos; violinist Efrem Zimbalist and pianist Harold Bauer playing the theme and variations from Beethoven's "Kreutzer" Sonata, and three solos by singers Marion Talley, Giovanni Martinelli and Anna Case. By all accounts, the show was a resounding success. A steady flow of shorts and part-talking features would follow, beginning with the second Vitaphone show on 7 October 1926. On 6 October 1927 "The Jazz Singer" premiered in New York. The other major Hollywood studios, anticipating a favorable public response to sound films, had been involved in clandestine negotiations since 1926 and now were scrambling to secure a share of this lucrative new market. -

The Rise, Fall, and Return of Vitaphone

The Rise, Fall, and Return of Vitaphone Brian Cruz Moving Image and Sound: Basic Issues and Training Prof. Ann Harris Fall 2014 Cruz 1 It was billed as “the event that will revolutionize motion pictures.” Advertisements promised that it “will thrill the world.” On August 6, 1926, at the Warner Theatre in Manhattan, Warner Bros. introduced the world to Vitaphone, the latest attempt to combine moving images with sound. For a $10 admission fee (plus tax), audiences were treated to a program of six shorts featuring synchronized music and dialogue, followed by the premiere of the John Barrymore film Don Juan with a soundtrack recorded by the New York Philharmonic. Whether Vitaphone’s debut really thrilled the world or not is debatable, but there’s no denying that it revolutionized motion pictures. Vitaphone became synonymous with sound films—whether they actually “talked” or not—and transformed Warner Bros. into one of the most powerful studios in Hollywood. Then, after the entire industry had finally converted to sound, Vitaphone suddenly disappeared and was quickly forgotten. Decades later, a chance discovery and the efforts of several dedicated enthusiasts would bring Vitaphone, or at least the memory of it, back to life. Early Failures Attempts to combine moving images with sound began as soon as the cinema was invented. Most involved playing a phonograph at the same time that a film was projected. In Europe, disc-based systems with derivative names like biophon, cronophone, elgéphone and kosmograph were developed in the early 1900s. None of these early systems proved successful because of their inability to keep sound in perfect synchronization with the picture, coupled with the fact that proper amplification to allow a theatre full of people to hear the sound was not yet possible.1 In 1913 Thomas Edison re-introduced the cylinder-based system called Kinetophone (much improved from its original 1895 design), in which a phonograph placed near the screen 1 A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures — The Beginning: 1876 – 1932. -

FALL 2009 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Table of QUARTERLY Contents 695 Volume 1 Issue 3

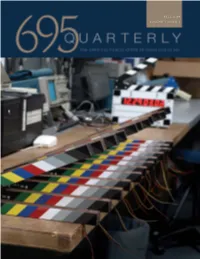

FALL 2009 VOLUME 1 ISSUE 3 Table of QUARTERLY Contents 695 Volume 1 Issue 3 14 18 27 Features Departments Playback Fury . 14 From the Editors & Business Representative 4 A production sound man’s nightmare From the President . 6 Dancing in the Moonlight . 18 Inventions & innovations from Mike Denecke News & Announcements . 8 The Sound Girls Brunch A Single-Feed Playback . 22 How hard can it be? Education & Training . 10 Tutorials and Fisher Boom training When Sound Was Reel 3 . 27 The end of the silent era Cover: The Quality Control bench at Denecke Inc. DISCLAIMER: I.A.T.S.E. LOCAL 695 and IngleDodd Publishing have used their best efforts in collecting and preparing material for inclusion in the 695 Quarterly Magazine but cannot warrant that the information herein is complete or accurate, and do not assume, and hereby disclaim, any liability to any person for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in the 695 Quarterly Magazine, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident or any other cause. Further, any responsibility is disclaimed for changes, additions, omissions, etc., including, but not limited to, any statewide area code changes, or any changes not reported in writing bearing an authorized signature and not received by IngleDodd Publishing on or before the announced closing date. Furthermore, I.A.T.S.E. LOCAL 695 is not responsible for soliciting, selecting or printing the advertising contained herein. IngleDodd Publishing accepts advertisers’ statement at face value, including those made in the advertising relative to qualifications, expertise and certifications of advertisers, or concerning the availability or intended usage of equipment which may be advertised for sale or rental. -

Frederick Wasser, Twentieth Century Fox, London, UK: Routledge, 2021, 283 Pp., $38.61 (Paperback)

International Journal of Communication 15(2021), Book Review 979–981 1932–8036/2021BKR0009 Frederick Wasser, Twentieth Century Fox, London, UK: Routledge, 2021, 283 pp., $38.61 (paperback). Reviewed by Amanda Ann Klein East Carolina University In the concluding chapter to Twentieth Century Fox, Frederick Wasser’s detailed industrial history of the Hollywood studio, the author writes, “The company started by William Fox after he got the government to break up a trust, has come full circle to Fox becoming part of a dominant oligopoly” (p. 250). This is a succinct moment of history writing, highlighting how the Fox Film Corporation’s story is bookended with monopolistic business practices, first as resistance and, then, decades later, again as acquiescence. This is a story, the author demonstrates, of film executives and their business decisions, rooted in a deft understanding of the markets and moviegoing culture as much as petty grievances and vendettas. As Wasser explains in his introduction, there were many ways to tell the story of Fox’s history: as a series of technological developments or in relation to major historical events, for example. Wasser’s choice to tell Fox’s story through its many executives and their differing visions for the studio illuminates how strongly economics have shaped the form and content of motion pictures since their invention. There is so much rich material from libraries and collections like the University of South Carolina’s archive of Fox Movietone reels and the Margaret Herrick Library’s cache of production files and personal papers that it is hard to believe Twentieth Century Fox is the first book-length scholarly study of the studio, which began in 1904 when James Stuart Blackton and William Fox pooled their money in order to purchase an amusement arcade in Brooklyn. -

Innovating De Forest Phonofilms Talkies in Australia Brian Yecies, University of Wollongong, Australia

Transformative Soundscapes: Innovating De Forest Phonofilms Talkies in Australia Brian Yecies, University of Wollongong, Australia The coming of sound to cinemas around the world traditionally has been included in the writings about great men and all-powerful companies and how their visions and integrated industry connections helped them maintain a dominating monopoly of the motion picture industry. Important and canonical reports of these business histories have been documented and offered by Tino Balio (1976; 1985; 1993), David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson (1985), Douglas Gomery (1986), Thomas Schatz (1988), John Belton (1994), Robert Sklar (1994), Donald Crafton (1997) and Ruth Vasey (1997) in the US and by Sally Stockbridge (1979), Susan Dermody (1981), John Tulloch (1982) and Graham Shirley and Brian Adams (1989) in Australia and by Rachael Low (1971) and Ian Jarvie (1992) in the UK. Also included in this history is a focus on the pioneering efforts of great experimenters and innovators such as Theodore Case, Lee de Forest, Earl Sponable in the US and Raymond Allsop, Arthur Smith and Clive Cross in Australia, who were all working outside and/or alongside the motion picture industry. The work of one person in particular -- Lee de Forest -- stands out in these motion picture business studies because of his contributions to the early development of synchronised motion picture sound technology. The detailed history surrounding de Forest's research experiences and achievements identify de Forest as a significant factor in the convergence of radio and cinema technology and a key figure who indirectly influenced the direction of the transition to sound (Geduld, 1975: 91).