Phoradendron in Mexico and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant Communities & Habitats

Plant Communities & Habitats CLASS READINGS Key to Common Trees of Bouverie Preserve Bouverie Vegetation Map This class will be held Deciduous & Evergreen Oaks of Bouverie Preserve almost entirely on the trail so dress Sun Leaves & Shade Leaves accordingly and bring Characteristics of the Oaks of Bouverie Preserve plenty of water Chaparral & Fire (California’s Changing Landscapes, Michael Barbour et.al., 1993) Bouverie Preserve Chaparral (DeNevers) ACR Fire Ecology Program Mixed Evergreen Forest (California’s Changing Landscapes, Michael Barbour et.al., 1993) Ecological Tolerances of Riparian Plants (River Partners) Call of the Galls (Bay Nature Magazine, Ron Russo, 2009) Oak Galls of Bouverie Preserve Leaves of Three (Bay Nature Magazine, Eaton & Sullivan, 2013) Mistletoe – Magical, Mysterious, & Misunderstood (Wirka) How Old is This Twig (Wirka) CALNAT: California Naturalist Handbook Chapter 4 (98-109, 114-115) Chapter 5 (117-138) Key Concepts By the end of this class, we hope you will be able to: Use a simple key to identify trees at Bouverie Preserve, Look around you and determine whether you are in oak woodland, mixed evergreen forest, riparian woodland, or chaparral -- and get a “feel” for each, Define: Plant Community, Habitat, Ecotone; understand how to discuss/investigate each with students, Stand under a large oak and guide students in exploring/discovering the many species that live on/around it, Find a gall on an oak leaf or twig and get excited about the lifecycle of the critters who live inside, Explain how chaparral plants are fire-adapted and look for evidence of these adaptations, Locate at least one granary tree and notice acorn woodpeckers that are guarding it, List some of the animals that rely on Bouverie’s oak woodland habitat, and Make an acorn whistle & count the years a twig has been growing SEQUOIA CLUB Resources When one tugs at a In the Bouverie Library single thing in nature, he A Manual of California Vegetation, second edition, finds it attached to the John Sawyer and Todd Keeler‐ Wolf (2009). -

"Santalales (Including Mistletoes)"

Santalales (Including Introductory article Mistletoes) Article Contents . Introduction Daniel L Nickrent, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA . Taxonomy and Phylogenetics . Morphology, Life Cycle and Ecology . Biogeography of Mistletoes . Importance of Mistletoes Online posting date: 15th March 2011 Mistletoes are flowering plants in the sandalwood order that produce some of their own sugars via photosynthesis (Santalales) that parasitise tree branches. They evolved to holoparasites that do not photosynthesise. Holopar- five separate times in the order and are today represented asites are thus totally dependent on their host plant for by 88 genera and nearly 1600 species. Loranthaceae nutrients. Up until recently, all members of Santalales were considered hemiparasites. Molecular phylogenetic ana- (c. 1000 species) and Viscaceae (550 species) have the lyses have shown that the holoparasite family Balano- highest species diversity. In South America Misodendrum phoraceae is part of this order (Nickrent et al., 2005; (a parasite of Nothofagus) is the first to have evolved Barkman et al., 2007), however, its relationship to other the mistletoe habit ca. 80 million years ago. The family families is yet to be determined. See also: Nutrient Amphorogynaceae is of interest because some of its Acquisition, Assimilation and Utilization; Parasitism: the members are transitional between root and stem para- Variety of Parasites sites. Many mistletoes have developed mutualistic rela- The sandalwood order is of interest from the standpoint tionships with birds that act as both pollinators and seed of the evolution of parasitism because three early diverging dispersers. Although some mistletoes are serious patho- families (comprising 12 genera and 58 species) are auto- gens of forest and commercial trees (e.g. -

Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau

ARIZONA COOPERATIVE E TENSION AZ1557 January 2012 Seiridium Canker of Cypress Trees in Arizona Jeff Schalau Introduction Leyland cypress (x Cupressocyparis leylandii) is a fast- growing evergreen that has been widely planted as a landscape specimen and along boundaries to create windbreaks or privacy screening in Arizona. The presence of Seiridium canker was confirmed in Prescott, Arizona in July 2011 and it is suspected that the disease occurs in other areas of the state. Seiridium canker was first identified in California’s San Joaquin Valley in 1928. Today, it can be found in Europe, Asia, New Zealand, Australia, South America and Africa on plants in the cypress family (Cupressaceae). Leyland cypress, Monterey cypress, (Cupressus macrocarpa) and Italian cypress (C. sempervirens) are highly susceptible and can be severely impacted by this disease. Since Leyland and Italian cypress have been widely planted in Arizona, it is imperative that Seiridium canker management strategies be applied and suitable resistant tree species be recommended for planting in the future. The Pathogen Seiridium canker is known to be caused by three different fungal species: Seiridium cardinale, S. cupressi and S. unicorne. S. cardinale is the most damaging of the three species and is SCHALAU found in California. S. unicorne and S. cupressi are found in the southeastern United States where the primary host is JEFF Leyland cypress. All three species produce asexual fruiting Figure 1. Leyland cypress tree with dead branch (upper left) and main leader bodies (acervuli) in cankers. The acervuli produce spores caused by Seiridium canker. (conidia) which spread by water, human activity (pruning and transport of infected plant material), and potentially insects, birds and animals to neighboring trees where new Symptoms and Signs infections can occur. -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site

Powell, Schmidt, Halvorson In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site Plant and Vertebrate Vascular U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center 2255 N. Gemini Drive Flagstaff, AZ 86001 Open-File Report 2005-1167 Southwest Biological Science Center Open-File Report 2005-1167 February 2007 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt , and William L. Halvorson Open-File Report 2005-1167 December 2006 USGS Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B. F, C. A. Schmidt, and W. L. Halvorson. 2006. Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Fort Bowie National Historic Site. -

Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes

Ornamental Horticulture Common Conifers in New Mexico Landscapes Bob Cain, Extension Forest Entomologist One-Seed Juniper (Juniperus monosperma) Description: One-seed juniper grows 20-30 feet high and is multistemmed. Its leaves are scalelike with finely toothed margins. One-seed cones are 1/4-1/2 inch long berrylike structures with a reddish brown to bluish hue. The cones or “berries” mature in one year and occur only on female trees. Male trees produce Alligator Juniper (Juniperus deppeana) pollen and appear brown in the late winter and spring compared to female trees. Description: The alligator juniper can grow up to 65 feet tall, and may grow to 5 feet in diameter. It resembles the one-seed juniper with its 1/4-1/2 inch long, berrylike structures and typical juniper foliage. Its most distinguishing feature is its bark, which is divided into squares that resemble alligator skin. Other Characteristics: • Ranges throughout the semiarid regions of the southern two-thirds of New Mexico, southeastern and central Arizona, and south into Mexico. Other Characteristics: • An American Forestry Association Champion • Scattered distribution through the southern recently burned in Tonto National Forest, Arizona. Rockies (mostly Arizona and New Mexico) It was 29 feet 7 inches in circumference, 57 feet • Usually a bushy appearance tall, and had a 57-foot crown. • Likes semiarid, rocky slopes • If cut down, this juniper can sprout from the stump. Uses: Uses: • Birds use the berries of the one-seed juniper as a • Alligator juniper is valuable to wildlife, but has source of winter food, while wildlife browse its only localized commercial value. -

Cupressaceae Calocedrus Decurrens Incense Cedar

Cupressaceae Calocedrus decurrens incense cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves lustrous, decurrent, much longer than wide • laterals nearly enclosing facials • seed cone with 3 pairs of scale/bract and one central 11 NOTES AND SKETCHES 12 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis lawsoniana Port Orford cedar Sight ID characteristics • scale leaves with glaucous bloom • tips of laterals on older stems diverging from branch (not always too obvious) • prominent white “x” pattern on underside of branchlets • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – no boss on apophysis 13 NOTES AND SKETCHES 14 Cupressaceae Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic white cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets slender, irregularly arranged (not in flattened sprays). • scale leaves blue-green with white margins, glandular on back • laterals with pointed, spreading tips, facials closely appressed • bark fibrous, ash-gray • globose seed cones 1/4, 4-5 scales, apophysis armed with central boss, blue/purple and glaucous when young, maturing in fall to red-brown 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Callitropsis nootkatensis Alaska yellow cedar Sight ID characteristics • branchlets very droopy • scale leaves more or less glabrous – little glaucescence • globose seed cones with 6-8 peltate cone scales – prominent boss on apophysis • tips of laterals tightly appressed to stem (mostly) – even on older foliage (not always the best character!) 15 NOTES AND SKETCHES 16 Cupressaceae Taxodium distichum bald cypress Sight ID characteristics • buttressed trunks and knees • leaves -

Phylogenetic Analyses of Juniperus Species in Turkey and Their Relations with Other Juniperus Based on Cpdna Supervisor: Prof

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGY APRIL 2015 Approval of the thesis MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA submitted by AYSUN DEMET GÜVENDİREN in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Biological Sciences, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Gülbin Dural Ünver Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Orhan Adalı Head of the Department, Biological Sciences Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Supervisor, Dept. of Biological Sciences METU Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Musa Doğan Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof. Dr. Zeki Kaya Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Prof.Dr. Hayri Duman Biology Dept., Gazi University Prof. Dr. İrfan Kandemir Biology Dept., Ankara University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sertaç Önde Dept. Biological Sciences, METU Date: iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Aysun Demet GÜVENDİREN Signature : iv ABSTRACT MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSES OF JUNIPERUS L. SPECIES IN TURKEY AND THEIR RELATIONS WITH OTHER JUNIPERS BASED ON cpDNA Güvendiren, Aysun Demet Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences Supervisor: Prof. -

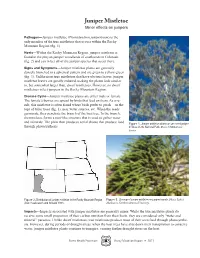

Juniper Mistletoe Minor Effects on Junipers

Juniper Mistletoe Minor effects on junipers Pathogen—Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is the only member of the true mistletoes that occurs within the Rocky Mountain Region (fig. 1). Hosts—Within the Rocky Mountain Region, juniper mistletoe is found in the pinyon-juniper woodlands of southwestern Colorado (fig. 2) and can infect all of the juniper species that occur there. Signs and Symptoms—Juniper mistletoe plants are generally densely branched in a spherical pattern and are green to yellow-green (fig. 3). Unlike most true mistletoes that have obvious leaves, juniper mistletoe leaves are greatly reduced, making the plants look similar to, but somewhat larger than, dwarf mistletoes. However, no dwarf mistletoes infect junipers in the Rocky Mountain Region. Disease Cycle—Juniper mistletoe plants are either male or female. The female’s berries are spread by birds that feed on them. As a re- sult, this mistletoe is often found where birds prefer to perch—on the tops of taller trees (fig. 1), near water sources, etc. When the seeds germinate, they penetrate the branch of the host tree. In the branch, the mistletoe forms a root-like structure that is used to gather water and minerals. The plant then produces aerial shoots that produce food Figure 1. Juniper mistletoe plants on one-seed juniper through photosynthesis. in Mesa Verde National Park. Photo: USDA Forest Service. Figure 2. Distribution of juniper mistletoe in the Rocky Mountain Region Figure 3. Closeup of juniper mistletoe on juniper branch. Photo: Robert (from Hawksworth and Scharpf 1981). Mathiasen, Northern Arizona University. Impacts—Impacts associated with juniper mistletoe are generally minor. -

Juniperus Occidentalis

Fire Effects Information System (FEIS) FEIS Home Page Table of Contents • SUMMARY INTRODUCTORY DISTRIBUTION AND OCCURRENCE BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS FIRE EFFECTS AND MANAGEMENT MANAGEMENT CONSIDERATIONS APPENDICES REFERENCES Figure 1—Western juniper. Photo by Joseph M. DiTomaso, University of California-Davis, Bugwood.org. Citation: Fryer, Janet L.; Tirmenstein, D. 2019 (revised from 1999). Juniperus occidentalis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/junocc/all.html [2019, June 26]. Revisions: The Taxonomy, Botanical and Ecological Characteristics, and Fire Effects and Management sections of this Species Review were revised in March 2019. New primary literature and a review by Miller et al. [145] were incorporated and are cited throughout this review. SUMMARY Western juniper occurs in the Pacific Northwest, California, and Nevada. Old-growth western juniper stands that established in presettlement times (before the 1870s) occur primarily on sites of low productivity such as claypan soils, rimrock, outcrops, the edges of mesas, and upper slopes. They are generally very open and often had sparse understories. Western juniper has established and spread onto low slopes and valleys in many areas, especially areas formerly dominated by mountain big sagebrush. These postsettlement stands (woodland transitional communities) are denser than most presettlement and old-growth woodlands. They have substantial shrub understories in early to midsuccession. Western juniper establishes from seed. Seed cones are first produced around 20 years of age, but few are produced until at least 50 years of age. Mature western junipers produce seeds nearly every year, although seed production is highly variable across sites and years. -

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts

Mistletoes: Pathogens, Keystone Resource, and Medicinal Wonder Abstracts Oral Presentations Phylogenetic relationships in Phoradendron (Viscaceae) Vanessa Ashworth, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Keywords: Phoradendron, Systematics, Phylogenetics Phoradendron Nutt. is a genus of New World mistletoes comprising ca. 240 species distributed from the USA to Argentina and including the Antillean islands. Taxonomic treatments based on morphology have been hampered by phenotypic plasticity, size reduction of floral parts, and a shortage of taxonomically useful traits. Morphological characters used to differentiate species include the arrangement of flowers on an inflorescence segment (seriation) and the presence/absence and pattern of insertion of cataphylls on the stem. The only trait distinguishing Phoradendron from Dendrophthora Eichler, another New World mistletoe genus with a tropical distribution contained entirely within that of Phoradendron, is the number of anther locules. However, several lines of evidence suggest that neither Phoradendron nor Dendrophthora is monophyletic, although together they form the strongly supported monophyletic tribe Phoradendreae of nearly 360 species. To date, efforts to delineate supraspecific assemblages have been largely unsuccessful, and the only attempt to apply molecular sequence data dates back 16 years. Insights gleaned from that study, which used the ITS region and two partitions of the 26S nuclear rDNA, will be discussed, and new information pertinent to the systematics and biology of Phoradendron will be reviewed. The Viscaceae, why so successful? Clyde Calvin, University of California, Berkeley Carol A. Wilson, The University and Jepson Herbaria, University of California, Berkeley Keywords: Endophytic system, Epicortical roots, Epiparasite Mistletoe is the term used to describe aerial-branch parasites belonging to the order Santalales. -

Conspecific Pollen on Insects Visiting Female Flowers of Phoradendron Juniperinum (Viscaceae) in Western Arizona

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 4 Article 7 1-16-2017 Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona William D. Wiesenborn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Wiesenborn, William D. (2017) "Conspecific pollen on insects visiting emalef flowers of Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) in western Arizona," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 4 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss4/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(4), © 2017, pp. 478–486 CONSPECIFIC POLLEN ON INSECTS VISITING FEMALE FLOWERS OF PHORADENDRON JUNIPERINUM (VISCACEAE) IN WESTERN ARIZONA William D. Wiesenborn1 ABSTRACT.—Phoradendron juniperinum (Viscaceae) is a dioecious, parasitic plant of juniper trees ( Juniperus [Cupressaceae]) that occurs from eastern California to New Mexico and into northern Mexico. The species produces minute, spherical flowers during early summer. Dioecious flowering requires pollinating insects to carry pollen from male to female plants. I investigated the pollination of P. juniperinum parasitizing Juniperus osteosperma trees in the Cerbat Mountains in western Arizona during June–July 2016. I examined pollen from male flowers, aspirated insects from female flowers, counted conspecific pollen grains on insects, and estimated floral constancy from proportions of conspecific pollen in pollen loads. -

Plant Palette - Trees 50’-0”

50’-0” 40’-0” 30’-0” 20’-0” 10’-0” Zelkova Serrata “Greenvase” Metasequoia glyptostroboides Cladrastis kentukea Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Gracilis’ Ulmus parvifolia “Emer I” Green Vase Zelkova Dawn Redwood American Yellowwood Slender Hinoki Falsecypress Athena Classic Elm • Vase shape with upright arching branches • Narrow, conical shape • Horizontally layered, spreading form • Narrow conical shape • Broadly rounded, pendulous branches • Green foliage • Medium green, deciduous conifer foliage • Dark green foliage • Evergreen, light green foliage • Medium green, toothed leaves • Orange Fall foliage • Rusty orange Fall foliage • Orange to red Fall foliage • Evergreen, no Fall foliage change • Yellowish fall foliage Plant Palette - Trees 50’-0” 40’-0” 30’-0” 20’-0” 10’-0” Quercus coccinea Acer freemanii Cercidiphyllum japonicum Taxodium distichum Thuja plicata Scarlet Oak Autumn Blaze Maple Katsura Tree Bald Cyprus Western Red Cedar • Pyramidal, horizontal branches • Upright, broad oval shape • Pyramidal shape • Pyramidal shape, develops large flares at base • Pyramidal, buttressed base with lower branches • Long glossy green leaves • Medium green fall foliage • Bluish-green, heart-shaped foliage • Leaves are needle-like, green • Leaves green and scale-like • Scarlet red Fall foliage • Brilliant orange-red, long lasting Fall foliage • Soft apricot Fall foliage • Rich brown Fall foliage • Sharp-pointed cone scales Plant Palette - Trees 50’-0” 40’-0” 30’-0” 20’-0” 10’-0” Thuja plicata “Fastigiata” Sequoia sempervirens Davidia involucrata Hogan