Neoliberalism and Trade Unions in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a Political Biography Darlington, RR

Book review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a political biography Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12270 Title Book review : Bob Crow : Socialist, Leader, Fighter : a political biography Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/43720/ Published Date 2017 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Bob Crow: Socialist, Leader, Fighter: A Political Biography. Gregor Gall. Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2017., ISBN: 978-1526100290, Price £20, hardback. During his term of office as general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT) during 2002-2014 until his early death at the age of 52, Bob Crow became one of the most widely known British union leaders of his generation. His stress on the virtues of militant resistance towards employers and government contributed to RMT members on the railways and London Underground organising (on a proportionate basis) probably more ballots for industrial action, securing more successful ‘yes’ votes, and taking strike action more often than any other union. In the process, Crow became the bête noire of the tabloid media, with the Evening Standard claiming he was ‘The Most Hated Man in London’. -

Mike Macnair

Paper of the Communist Party of Great Britain weekly No need for a party? Mike n Labour makes gains workern Non-Labour left Macnair reports from the n Lib Dem slump US Platypus convention n CPGB aggregate No 865 Thursday May 12 2011 Towards a Communist Party of the European Union www.cpgb.org.uk £1/€1.10 CONSTITUTIONAL CRISIS BECKONS 8 May 12 2011 865 US LEFT No need for party? The US Platypus grouping does not have a political line because there is ‘no possibility of revolutionary action’. Mike Macnair reports on its convention attended the third annual Platypus about madness and the penitentiary, as International Convention in Chi- well as about the history of sexuality, Icago over the weekend April 29- have been falsified by historians. May 1. The Platypus Affiliated So- And, though he identified Foucault’s ciety is a, mainly student, left group tendency to marginalise class politics, of an odd sort (as will appear further he saw this as merely a product of the below). Its basic slogan is: ‘The left defeat of the left, rather than as an is dead; long live the left’. Starting active intervention in favour of popular very small, it has recently expanded frontism. Hence he missed the extent rapidly on US campuses and added to which the Anglo-American left chapters in Toronto and Frankfurt. academic and gay/lesbian movement Something over 50 people attended reception of Foucault was closely tied the convention. to the defence of extreme forms of The fact of Platypus’s rapid growth popular frontism by authors directly on the US campuses, though still as or indirectly linked to Marxism yet to a fairly small size, tells us that Today, for whom it was an instrument in some way it occupies a gap on the against the ‘class-reductionist’ ideas US left, and also tells us something of Trotskyists. -

No. 207, Summer, 2009

No 207 SUMMER 2009 40p Newspaper of the Spartacist League Forge a multiethnic revolutionary workers party! if" publish helow an edited alld Depression wasn't Roosevelt's New .~~ -'--- __ .1. ~_ •• ~.~. ___ ............. ___ •• ' f (}n~'&8'&W UJ (P. MONI',_ Deal, but World War 11. It was when . gil'cll h)' cOlJlrade Julia Effie,}' at a the imperialist governments In Spartacist League public meeting ;n Britain and the US mobilised their London on 4 April. economies for WWlI that they fully The ongoing world capitalist reces adopted Keynes's programme of sion is having a tremendous impact on deficit spending for "public works" the British economy and inflicting -- battleships, bombers, tanks and severe hardship on working people. finally atomic hombs. Thc lahour Across Britain the rate of home repos movement must oppose protec sessions is rising while the nllmber of tionism and fight fur international job losses is cnonnolls. The working~class solidarity. crisis has demonstrated quill..' Production itself is socialised openly the hmlkruptcy and irra~ Unions must defend immigrant workers! and international in scope tionality of the capitalist sys~ and the international working tem and what the leaders of all class must he mohilised capitalist countries agree on is Down with chauvinist construction strikes! across national and other that working people will be divisions. made to pay for it. It also confinTIs the Marxist understanding that ultimately Reactionary strikes tht..:rc is no answer to the boom-and-bust Since January a series of reactionary cycles of capitalism short of proletarian and virulently chauvinist strikes and socialist revolution that takes power out protests havc taken place on building of the hands of the capitalist ruling class sites at Britain's power stations and oil and replaces it with a planned, refineries. -

A Letter to Trade Union National Executive Committee Members

Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition, 17 Colebert House, Colebert Avenue, London, E1 4JP A letter to trade union national executive committee members Dear comrade, I am writing to invite you to consider joining the national steering committee of the recently relaunched Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC). As you may recall TUSC was set-up in 2010, co-founded amongst others by the late Bob Crow, with trade unionists at its core (a brief history is available at http://www.tusc.org.uk/txt/429.pdf). Our founding aim was to help in the process of re-establishing a political voice for the working class given, at that point, the transformation of the Labour Party into Tony Blair’s New Labour and its role in implementing the austerity unleashed by the 2007-08 financial crash. As our name says we are a coalition and all of the component elements of TUSC have played their part alongside other campaigners in the struggles of the last decade against attacks on jobs, services and conditions – in the workplace, in our communities, and in the trade unions. But we have also been prepared to stand in elections where necessary, believing that to leave politicians who are carrying out cuts unchallenged at the ballot box, is to voluntarily give up a weapon that could be used in the anti-austerity struggle. This is particularly so in local government, in which councillors are the direct employers and providers of local services. In this situation to positively decide not to have an anti-austerity candidate standing when cuts are being made would be to give an effective vote of confidence to the local authority’s policies. -

Congress Report 2004

Congress Report 2004 The 136th annual Trades Union Congress 13-16 September, Brighton Contents Page General Council members 2004 – 2005-03-15………………………………..4 Section one - Congress decision…………………………………………...........7 Part 1 Resolutions carried.............................. ………………………………………………8 Part 2 Motion remitted………………………………………………… ............................30 Part 3 Motion Lost…………………………………………………….................................31 General Council statement on Europe………………………………….……. ......32 Section two – Verbatim report of Congress proceedings Day 1 Monday 13 September ......................................................................................34 Day 2 Tuesday 14 September……………………………………… .................................73 Day 3 Wednesday 15 September...............................................................................119 Day 4 Thursday 16 September ...................................................................................164 Section three - unions and their delegates ............................................187 Section four - details of past Congresses ...............................................197 Section five - General Council 1921 – 2004.............................................200 Index of speakers .........................................................................................205 3 General Council Members John Hannett 2004 – 2005 Union of Shop Distributive and Allied Workers Dave Anderson Pat Hawkes UNISON National Union of Teachers Jonathan Baume Billy Hayes FDA Communication -

St Joseph the Worker and Bob Crow

St Joseph the Worker and Bob Crow John Battle 1 May is the Feast of St Joseph the Worker, a day on which the Church encourages us to celebrate the value of work, and the dignity and rights of workers. These issues are already in sharp focus this week for Londoners, due to strike action by London Underground workers. John Battle asks to what extent the understanding of trade unions in Catholic Social Teaching matches that of the late union leader, Bob Crow. Any London-based readers are Caritas in veritate , his successor likely to be heading into the Pope Benedict XVI defined Feast of St Joseph the Worker ‘decent work’ as: on 1 May having experienced the chaos of a two-day tube ...work that expresses the strike organised by the Rail, essential dignity of every man Maritime and Transport Union and woman in the context of (RMT), the second such strike their particular society: work that is freely chosen, effect- to take place this year. The ively associating workers, public attitude to this industrial both men and women, with action, which caused widespre- the development of their ad disruption to London’s tran- community; work that sport network, has been largely enables the worker to be unsympathetic. The fact that Photos by Lawrence OP & Karen Fletcher at flickr.com respected and free from any industrial strikes are an increas- form of discrimination; work ingly rare occurrence (not least because it is now that makes it possible for families to meet their legally much harder for union members to take such needs and provide schooling for their children, action) has meant that, when they do occur, they are without the children themselves being forced into labour; work that permits the workers to regarded by many as throwbacks to a bygone age that organise themselves freely, and to make their have no place in a modern economy. -

Crow -V- Johnson

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 1982 (QB) Case No: HQ12D01579 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 16/07/2012 Before : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : Robert Crow Claimant - and - Boris Johnson Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Jonathan Crystal (instructed by Thompsons Solicitors) for the Claimant David Glen (instructed by Collyer Bristow LLP) for the Defendant Hearing dates: 16 July 2012 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment I direct that pursuant to CPR PD 39A para 6.1 no official shorthand note shall be taken of this Judgment and that copies of this version as handed down may be treated as authentic. ............................. THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE TUGENDHAT Crow v. Johnson Approved Judgment Mr Justice Tugendhat : 1. The Claimant in this action (“Mr Crow”) is the General Secretary of the RMT, the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers. In this libel action he sues the Defendant (“Mr Johnson”), who is now the Mayor of London, in respect of leaflets that Mr Johnson published as part of his campaign to secure re-election to that office at the election held on 3 May 2012. As every Londoner knows, Mr Johnson’s predecessor in the office of Mayor of London was Mr Ken Livingstone. Mr Livingstone had been Mayor until 2008, when Mr Johnson was first elected. Mr Livingstone was also a candidate for election in May 2012. Mr Livingstone is not making any claim in this action and is not a party to it. 2. Mr Crow was not a candidate for election, but he is referred to as Bob Crow in the leaflets he complains of. -

QOOOE2 As Their Plants They Cultivate

For National The Independence, Democracy Democrat and Jobs Paper of the Campaign against Euro-federalism ISSN 0967-3806 Number 140 March-April 2014 50p EU 3.5 million jobs lie uring the recent EU debates stitute of Economic and Social Research between arch euro fanatic (NIESR) estimated, using similar meth- D Nick Clegg and UKIP leader ods, that up to 3.2m UK jobs "are now Nigel Farage the Lib Dem leader associated directly with exports of dragged up the well-worn lie that 3.5 goods and services to other EU coun- million jobs in Britain depend on EU tries." It warned that: "there is no a pri- membership. ori reason to suppose that many of This claim is based on one study car- these, if any, would be lost perma- ried out over ten years ago which the nently if Britain were to leave the EU." researcher himself has since repudi- In fact, NIESR director Jonathan Portes, ated. who is certainly no Eurosceptic, de- scribed this research as "past [its] sell- EUBG to Afrrica page 2 report by Brian Denny by date." Yet it is still being pumped out by the The list of factories, car plants, engi- right wing campaign group British In- neering centres and jobs being stripped fluence, headed up by Tory spin doctor out of Britain's manufacturing base and Peter Wilding and one Peter Mandel- transferred abroad due to the logic of son, as well as by trade unions that the EU single market is never men- should know better such as Unite. -

Libya, Anti-Imperialism, and the Socialist Party

Published on Workers' Liberty (http://www.workersliberty.org) Libya, anti-imperialism, and the Socialist Party By Sean Matgamna This is a copy-edited and slightly expanded version of the text printed in WL 3/34 Libya, anti-imperialism, and the Socialist Party Did Taaffe equate the Libyan rebels with the Nicaraguan contras? [3] Anything other than "absolute opposition" means support? [4] Intellectual hooliganism and AWL's "evasions" [5] What is more important in the situation than stopping massacre? [6] Bishop Taaffe and imperialism [7] What is the "anti-imperialist" programme in today's world? [8] From semi-colony to regional power [9] Taaffe's record as an anti-imperialist [10] The separation of AWL and the Socialist Party [11] Militant in the mid 1960s [12] How did we come to break with Militant? Anti-union laws [13] What is a Marxist perspective? [14] Peaceful revolution [15] Our general critique of Militant's politics [16] "We can't discuss what Grant and Taaffe can't reply to" [17] The US in Iraq and union freedoms [18] Socialists and the European Union [19] Toadying to Bob Crow [20] Ireland: why socialists must have a democratic programme [21] Conclusion: Pretension [22] Appendix: Militant and the Labour Party, 1969-87 - a strange symbiosis [23] What We Are And What We Must Become: critique of Militant, written in 1966, which became the founding document of the AWL tendency, is available at http://www.workersliberty.org/wwaawwmb The RSL (Militant) in the 1960s: a study of passivity: an account of how What We Are And What We Must Become came to be written, and the battle around its ideas. -

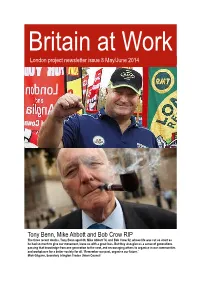

Tony Benn, Mike Abbott and Bob Crow

Britain at Work London project newsletter issue 8 May/June 2014 Tony Benn, Mike Abbott and Bob Crow RIP The three recent deaths, Tony Benn aged 88, Mike Abbott 74, and Bob Crow 52, whose life was cut so short as he had so much to give our movement, leave us with a great loss. But they also give us a sense of generations passing that knowledge from one generation to the next, and encouraging others to organise in our communities and workplaces for a better society for all. ‘Remember our past, organise our future.’ Mick Gilgunn, Secretary Islington Trades Union Council Tony Benn Arguments for Socialism/The End of an Era The Inheritance: The Labour Movement ‘The history of Tony Benn’s 'The End of An Era' Diaries 1980-90 the Labour movement cannot only be seen as the story (Arrow, London, 1994) Thursday May 31 1984 Over the of Christian philosophers or, for that matter, trade union last few days there have been terrible scenes outside the leaders or Labour parliamentarians. For ideas without Orgreave Coke Depot, where 7,000 pickets have been action will for ever remain as academic works, scholarly attacked by mounted and foot police with riot shields and but sterile and leaders are only important in so far as helmets. It looks like civil war. You see the police they truly represent those whom they serve.… The real charging with big staves and police dogs chasing miners history of any popular movement is made by those, across fields, then miners respond by throwing stones almost anonymous, who throughout history have fought and trying to drag a telegraph pole across a road; there for what they believe in, organised others to join them, are burning buildings and road blocks. -

Socialist Fight No.11

Socialist Fight Issue No. 11 Winter 2012 Price: Concessions: 50p, Waged: £2.00 €3 Editorial: TU leaders must fight for needs budgets! No Cuts; Build the Rank and File fightback! The Counihan Homelessness Campaign In Kilburn Square fighting Brent Council’s attempt to drive the family out of Brent Contents Page 14: Plebgate, experts and the prosecution Page 25: ‘Liberation’ in Libya today, By the service, By Michael Holden. Liaison Committee of the Fourth International. Page 2: Editorial: TU leaders must fight for Page 15: Statement by the Irish Republican Page 29: Refutation of Prof. Grover Furr needs budgets! Prisoners Support Group, Letter to the Irish By Mike Ely and Socialist Fight. Page 4: 200,000 March against Austerity in Post, From Charlie Walsh. Page 32: The True Levellers or Diggers By Laur- London, By Graham Durham. Page 16: Lights and Shadows from Fifty Shades ence Humphries Page 5: The Third Grand Old Duke of York of Grey, By Aggie McCallum. Page 33: Defend the DSM of South Africa. Demo: TU leaders must fight for needs budg- Page 17: Jim Fixed it for the Ruling Class Child Page 34: Socialist Fight: For an International ets!, GRL flyer for TUC demo. Abusers, By Antonio Las Sogas & Brighid O'Duinn. Solidarity Campaign with the striking minework- Page 6: The Counihan Campaign and the Hous- Page 18: Tree planting ceremony for Terence ers of South Africa. ing Crisis By Gerry Downing. MacSwiney (1879-1920), Lord Major of Cork, By Page 35: Solidarity with Marikana Miners, By Page 7: The true role of the National Shop Stew- Austin Harney. -

CONTENTS in This Editorial Issue in the News 4-5 EU: Exit Left 6-7 Women’S Liberation 8

CONTENTS in this editorial issue In the News 4-5 EU: Exit Left 6-7 Women’s liberation 8 Ukraine Ukraine’s crisis 9-10 p9-10 Referendum revisited 11-12 Back2Basics 13 Toxic Tories 14 Venezuela TUC Young p18-19 Members 15-16 Sma’ Shot Day 17 Venezuela fights back 18-19 BobCrow Bob Crow 20 p20 Tony Benn 21 Revolutionary Sounds 22-23 May2014 Volume21,Issue34 Layout&design: Ben Stevenson & James Rodie What We Stand For Print: Communist Party Publishedby: YCL, Ruskin House, 23 Coombe 24 Rd, CR0 1BD Frontpic:Tom Page (CC) 3 IN THE NEWS inthenews Youthmark65years ofinvasionandwar he world’s anti-imperi- alist youth have marked pic: Jos van Zetten T65 years of Nato’s “wars, dictatorship, assassinations, invasions and occupations” Liverpool with a fresh call to destroy the imperialist bloc. stands up The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation was founded in April 1949 as the military arm for services of Western imperialism, led by nperturbed by the recent the United States. loss of two of its giants, “Nato has been the greatest Uthe labour movement in military tool of imperialism Liverpool turned out last month in the past 65 years, directly to show its support for the pub- and indirectly connected with lic sector which has been cut by the biggest crimes against nearly 30 per cent in Merseyside the peoples of the world that An anti-Nato demonstration in Strasbourg compared to 2 per cent in the took place in all those years,” Tory heartlands in the south. said the World Federation of “Nato’s history is directly tion to strengthen the national The demonstration snaked Democratic Youth.