Agricultural Land Abandonment and Farmers' Perceptions Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEF Assisted Schools (SAS)

Sindh Education Foundation, Govt. of Sindh SEF Assisted Schools (SAS) PRIMARY SCHOOLS (659) S. No. School Code Village Union Council Taluka District Operator Contact No. 1 NEWSAS204 Umer Chang 3 Badin Badin SHUMAILA ANJUM MEMON 0333-7349268 2 NEWSAS179 Sharif Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 3 NEWSAS178 Yasir Abad Thari Matli Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 4 NEWSAS205 Haji Ramzan Khokhar UC-I MATLI Matli Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 5 NEWSAS177 Khan Wah Rajo Khanani Talhar Badin HAPE DEVELOPMENT & WELFARE ASSOCIATION 0300-2632131 6 NEWSAS206 Saboo Thebo SAEED PUR Talhar Badin ZEESHAN ABBASI 0300-3001894 7 NEWSAS175 Ahmedani Goth Khalifa Qasim Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 8 NEWSAS176 Shadi Large Khoski Tando Bago Badin GREEN CRESCENT TRUST (GCT) 0304-2229329 9 NEWSAS349 Wapda Colony JOHI Johi Dadu KIFAYAT HUSSAIN JAMALI 0306-8590931 10 NEWSAS350 Mureed Dero Pat Gul Mohammad Johi Dadu Manzoor Ali Laghari 0334-2203478 11 NEWSAS215 Mureed Dero Mastoi Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 12 NEWSAS212 Nabu Birahmani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION & REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 13 NEWSAS216 Phullu Qambrani Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 14 NEWSAS214 Shah Dan Pat Gul Muhammad Johi Dadu TRANSFORMATION AND REFLECTION FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT (TRD) 0334-0455333 15 RBCS002 MOHAMMAD HASSAN RODNANI -

Estimates of Receipts Revenue Collecting Office (Rco) Level

Volume - II Part - A 2021-22 ESTIMATES OF RECEIPTS REVENUE COLLECTING OFFICE (RCO) LEVEL Finance Department Government of Sindh CONTENTS ESTIMATES OF RECEIPTS 2021-22 REVENUE COLLECTING OFFICE(RCO) LEVEL PART-A S.No. DESCRIPTION PAGES Department-wise Receipt Summary 2021-22 i - iii 1 Finance (Foreign and Domestic Borrwing) 1-7 2 Food Department (Cash Credit Accomodation) 8-36 3 General Administration 37-62 4 Finance Department 63-100 5 Superannuation and Pension 101-125 6 Sindh Revenue Board 126-130 7 Excise & Taxation Department 131-207 8 Tax Management - Board of Revenue 208-373 9 Home Department 374-394 10 Police 395-448 11 Jails and Detention Places 449-479 12 Law and Parliamentary Affairs 480-533 13 Agriculture 534-628 14 Food Department (Establishment) 629-633 15 Livestock & Fisheries 634-667 16 Board of Revenue (Land Management) 668-698 17 Cooperatives 699-717 18 Irrigation 718-769 19 Power and Energy 770-790 20 Mines and Minerals 791-806 21 Industries 807-817 22 Labour 818-823 23 Works and Services 824-919 24 Education Works 920-942 25 Transport 943-965 26 Weight and Measures 966-1010 ( i ) RECEIPTS SUMMARY BUDGET REVISED BUDGET S.No. DESCRIPTION ESTIMATE ESTIMATE ESTIMATE 2020-21 2020-21 2021-22 Rs. Rs. Rs. A CURRENT AND DEVELOPMENT RECEIPTS 1 Revenue Receipts 1,088,105,500,000 968,676,800,000 1,213,904,068,440 2 Current Capital Receipts 25,000,000,000 35,000,000,000 50,100,800,000 3 Development Capital Receipts 54,640,700,000 38,287,472,000 71,163,701,000 TOTAL (A) 1,167,746,200,000 1,041,964,272,000 1,335,168,569,440 B- STATE TRADING RECEIPTS 4 Sate Trading Receipts 50,022,000,000 81,022,000,000 93,324,210,000 5 Commercial Loans for State Tradings 39,784,000,000 39,784,000,000 57,740,000,000 TOTAL (B) 89,806,000,000 120,806,000,000 151,064,210,000 1,257,552,200,000 1,162,770,272,000 1,486,232,779,440 ( ii ) BREAKUP OF ESTIMATE OF RECEIPTS 2021-22 S.No. -

PDMA Sindh Floods 2015 Safe Evacuation Report 9

No. PDMA(S) / 7 (87) / 2015 PROVINCIAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (PDMA) REHABILITATION DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT OF SINDH FLOODS 2015 - SAFE EVACUATION REPORT (SER) - 9 Date of Issue: 02.08.2015 Time of Issue: 1830 hours PROVISIONAL REPORT and SUBJECT TO CHANGE POPULATION IN RELIEF CAMPS LIVE STOCK EVACUATED No. of Relief Taluka No. of Capacity of No. of Villages *Persons Camps / Tent Children S# District From Where Evacuation Union Relief Camp / Infants Large Small Evacuated Evacuated Villages Male Female Under 12 Total Total Made / Carried out Councils Tent Village Under 5 Yrs animal animal Established Yrs 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 LARKANA DIVISION Bakrani, Rato Dero, 1 Larkano 8 120 13810 18 5,000 RA RA RA RA 2,000 RA RA RA Dokri, Larkano Shikarpur, Khanpur, 2 Shikarpur 6 56 5,730 20 3,300 1,470 1,715 1,345 1,200 5,730 2,800 3,385 6,185 Garhi Yasin & Lakhi Kandhkot & 1955 3 Kashmore 10 240 95,765 21 687 590 423 509 2,209 14,249 19,766 34,015 Kashmore families SUKKUR DIVISION Rohri, Pano Aqil, 300-400 4 Sukkur 10 202 59,223 10 3,565 3,019 2,147 1502 10,233 12,453 9,543 21,996 New Sukkur each camp Ghotki 5 Ghotki 10 Partially 283 57,000 8 21,000 7,254 7,096 2,114 906 17,370 8,661 10,995 19,656 & Ubauro Khairpur, Kingri, 6 Khairpur 13 377 69,865 18 3400 4,340 3,723 1,238 541 9,842 6,382 5,990 12,372 Gambar, Sobho Dero SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD DIVISION Shaheed Sakrand, Qazi 7 9 51 5,500 60 5500 28 35 44 79 186 900 730 1,630 Benazirabad Ahmed N.Feroze, Moro, 8 N. -

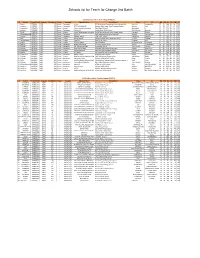

Schools List for Teach for Change 2Nd Batch

Schools list for Teach for Change 2nd Batch ESSP Schools List For Teach for Change (PHASE-II) S # District School Code Program Enrollment Phase Category Operator Name School Name Taluka UC ND NM NS ED EM ES 1 Sukkur ESSP0041 ESSP 435 Phase I Elementary Ali Bux REHMAN Model Computrized School Mubrak Pur. Pano Akil Mubarak Pur 27 40 288 69 19 729 2 Jamshoro ESSP0046 ESSP 363 Phase I Elementary RAZA MUHAMMAD Shaheed Rajib Anmol Free Education System Sehwan Arazi 26 28 132 67 47 667 3 Hyderabad ESSP0053 ESSP 450 Phase I Primary Free Journalist Foundation Zakia Model School Qasimabad 4 25 25 730 68 20 212 4 Khairpur ESSP0089 ESSP 476 Phase I Elementary Zulfiqar Ali Sachal Model Public School Thari Mirwah Kharirah 27 01 926 68 31 711 5 Ghotki ESSP0108 ESSP 491 Phase I Primary Lanjari Development foundation Sachal Sarmast model school dargahi arbani Khangarh Behtoor 27 49 553 69 20 705 6 ShaheedbenazirabaESSP0156 ESSP 201 Phase I Elementary Amir Bux Saath welfare public school (mashaik) Sakrand Gohram Mari 26 15 244 68 08 968 7 Khairpur ESSP0181 ESSP 294 Phase I Elementary Naseem Begum Faiza Public School Sobhodero Meerakh 27 15 283 68 20 911 8 Dadu ESSP0207 ESSP 338 Phase I Primary ghulam sarwar Danish Paradise New Elementary School Kn Shah Chandan 27 03 006 67 34 229 9 TandoAllahyar ESSP0306 ESSP 274 Phase I Primary Himat Ali New Vision School Chumber Jarki 25 24 009 68 49 275 10 Karachi ESSP0336 ESSP 303 Phase I Primary Kishwar Jabeen Mazin Academy Bin Qasim Twon Chowkandi 24 51 388 67 14 679 11 Sanghar ESSP0442 ESSP 589 Phase I Elementary -

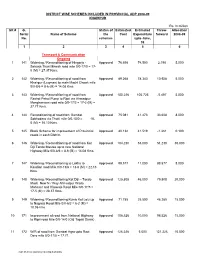

ADP 08-09 All Districts(CP-RAM)6/25/2004 Rs

DISTRICT WISE SCHEMES INCLUDED IN PROVINCIAL ADP 2008-09 KHAIRPUR Rs. In million SR # G. Status of Estimated Estimated Throw- Allocation Serial Name of Scheme the Cost Expenditure forward 2008-09 No. schemes upto June, 08 12 3456 Transport & Communication Ongoing 1 141 Widening / Reconditioning of Hingorja - Approved 76.698 74.500 2.198 5.000 Seharja Thari Mirwah road mile 0/0-17/0 = 17- 0 (M) = 27.37 Kms. 2 142 Widening / Reconditioning of road from Approved 89.268 78.340 10.928 5.000 Khairpur (Luqman) to main Machi Chowk mile 0/0-8/6 = 8-6 (M) = 14.08 Kms 3 143 Widening / Reconditioning of road from Approved 100.226 105.723 -5.497 5.000 Rashdi Petrol Pump to Ripri via Ahmedpur Manghanwari road mile 0/0-17/2 = 17-2 (M) = 27.77 Kms. 4 144 Reconditioning of road from Gambat Approved 75.081 41.473 33.608 8.000 Sobhodero via Thatti mile 0/0-10/0 = 10- 0 (M) = 16.10 Kms. 5 145 Block Scheme for improvement of Provincial Approved 40.138 41.519 -1.381 0.100 roads in each District. 6 146 Widening / Reconditioning of road from Kot Approved 104.230 53.000 51.230 30.000 Diji Tando Mastee up to new National Highway Mile 0/0-8/6 = 8-6 (M) = 14.08 Kms. 7 147 Widening / Reconditioning to Lakha to Approved 99.577 11.000 88.577 8.000 Kandiari road Mile 0/0-13/6 = 13-6 (M) = 22.13 Kms. 8 148 Widening / Reconditioning Kot Diji – Tando Approved 125.808 46.000 79.808 20.000 Masti New N / Way Ahmedpur Wada Mahasar and Khowaja Road Mile 0/0-17/5 = 17-5 (M) = 28.37 Kms. -

Khairpur, Sindh 5/3/1980 Matric 15/07/2014 Sheikh

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE NAME BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 30738 NAIMAT ULLAH NASRULLAH P/O RIB MEHAR SHAH VIA KHUHRA , KHAIRPUR, SINDH 5/3/1980 MATRIC 15/07/2014 SHEIKH 2 25955 SHAMSHAD MATARO KHAN VILL MITHO MARI P/O KHANPUR TALUKA DISTT, 1-12- MATRIC 18/10/2014 ALI KHAIRPUR, KHAIRPUR, SINDH 1972 3 39041 ABDULLAH UMEED ALI GOTH KHAN PUR TEH, & DISTT, KHAIR PUR, KHAIRPUR, 23-11- MATRIC 20/10/2014 SINDH 1966 4 33075 SHAHIDA MUHAMMAD P/O BABARLO VILL. DUHOON IBRAHIMSHAH, 4/3/1979 MATRIC 28/10/2014 BANO BACHAL KHAIRPUR, SINDH 5 40550 SHOUKAT ALI KEWRO KHAN VILLAGE BULHARO P/O COAT TEH, KHAS , KHAIRPUR, 6-2-1983 MATRIC 15/1/2015 BURDI SINDH 6 36796 DULAHNO BODA RAM SABO DERO DISTT,, KHAIRPUR, SINDH 2-3-1955 MATRIC 2/4/2015 MAL KHEMANI 7 28616 YAR SHAMAN AL-FAQUEER HOMOEO STORE DARGHAROAD PIR JO 1-2-1979 FA 13/10/2015 MUHAMMAD CHANNA GOTH , KHAIRPUR, SINDH 8 49393 NASIM RAZA QASIM RAZA H-NO.1-A/34 BADA ALAM , KHAIRPUR, SINDH 18/1/1972 MATRIC 14/10/2015 SAYED 9 30746 HUBDAR ALI ALLAH DAD P/O LUQMAN JAN WERI MOH, AL FAZAL HOUSE 10-7- FA 19/11/2015 KHAIRPUR MIRS, KHAIRPUR, SINDH 1976 10 39949 MUHAMMAD ABDULLAH AZIZ DAWAKHANA RANIPUR., KHAIRPUR, SINDH 20/1/1940 30/12/2015 MALOOK 11 39037 ABDUL ABDUL RAZAK NEAR JAMILA MOSQUE LUQMAN MOH: MEMON , 1-4-1958 MATRIC 28/1/2016 JABBAR MEMON KHAIRPUR, SINDH MEMON 12 41770 ABDUL LATIF MUAHMMAD P.O.SETHARJA., KHAIRPUR, SINDH 15/8/1966 MATRIC 25/3/2016 SADIQ 13 41841 ABID HUSSAIN MUHAMMAD MOHSIN SHAH AGRICULTUR FARM SITHAJA 3-3-1987 MATRIC 28/3/2016 SARDAR -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

Sindh Community Mobilization Program

SINDH COMMUNITY MOBILIZATION PROGRAM Quarterly Progress Report – Year IV, Quarter II (January 1, 2017 – March 31, 2017) Date: April 30, 2017 CMP is made possible by the support of the American People through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). CMP is implemented by International Relief and Development (IRD) under Contract Award No: AID-391-C-13-00006. This report was produced for review by USAID. CMP Year IV, Quarter II Report 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................................ 2 ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. PROGRAM SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 6 2. SUMMARY OF ACCOMPLISHMENTS DURNG REPORTING PERIOD....................................... 7 3. STATUS OF THE ACTIVITIES AS PER THE COMPONENTS ......................................................... 9 3.1. Component I: Increase Community Involvement in the GOS Reforms of Merging, Consolidating, and Upgrading Schools ......................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Component II: Improve Community and District Government Coordination for Increased Girls’ Enrollment .......................................................................................................................................... -

Airlift Target Locations, Sindh Province

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !( ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !( ! (! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Goth Goth 67°20'E 67°30'E 67°40'E 67°50'E 68°0'E 68°10'E Allahdad 68°20'E Gauhar Goth Firoz Haidarpur 68°30'E 68°40'E ! ! ! ! Khan Khan Wagha ! Goth Nasir Goth Goth Goth Rasul Khan Dasti Dheran Kalati Bakhsh Goth Attar Faqir Khan Wagha Bhangar Goth Abdul 28°20'N ! ! ! ! ! 28°20'N ! ! Goth Ghafur Goth Dur Muhammad Muhammad Goth Goth Husain Goth Nur Goth Dur Jamali Sohnipur Sohbdar Yar Ali Mamal Muhammad Muhammad ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bahadarpur ! Bahadarpur ! ! ! Goth Faizabad Chachar Goth Ali Goth ! Goth Data Goth Gulab Bakhsh Sahibdina Tajpur Dang Wah Khan Domki Machhi Khosa Somra Zangipur ! ! Dera ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Dilawarpur Goth Umar Goth Goth Alan Khan Babar Sher Khan Dasti Murad Jamali Tehsil Jhat Pat Tehsil Wasand Goth Khuda Muhammad Jatol Dil Jhal Kator Lohra Bakhsh Murad Odhano ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Balach Jacobabad Nasirabad District !(H Goth Rojhan Goth Gul Goth Haji Goth Hasil (! Jan Miral Thul Naubatpur Sathi Kohna Muhammad Khan Domki Khan Domki Muhammad Nau (!H! ! ! ! ! ! ! (!H ! ! ! Gandawa Goth Goth (!H Shah Beg Jani Daman Mundrani Dero Shah Bhambul Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Khanpur -

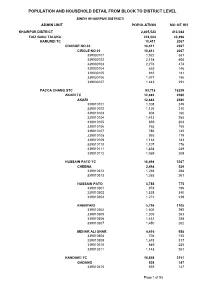

Khairpur Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (KHAIRPUR DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH KHAIRPUR DISTRICT 2,405,523 413,044 FAIZ GANJ TALUKA 224,004 43,496 KARUNDI TC 10,411 2067 CHARGE NO 03 10,411 2067 CIRCLE NO 01 10,411 2067 339030101 1,922 381 339030102 2,114 408 339030103 2,276 474 339030104 663 146 339030105 916 181 339030106 1,077 186 339030107 1,443 291 PACCA CHANG STC 93,718 18239 AKARI TC 12,883 2380 AKARI 12,883 2380 339010101 1,308 245 339010102 1,126 210 339010103 808 160 339010104 1,413 265 339010105 959 204 339010106 765 155 339010107 786 145 339010108 955 179 339010109 1,133 183 339010110 1,107 176 339010111 1,454 249 339010112 1,069 209 HUSSAIN PATO TC 16,498 3367 CHEENA 2,498 529 339010312 1,235 268 339010313 1,263 261 HUSSAIN PATO 3,788 775 339010301 978 196 339010302 1,538 340 339010303 1,272 239 KHENYARI 5,796 1105 339010304 1,606 292 339010305 1,309 263 339010306 1,431 288 339010307 1,450 262 MEHAR ALI UNAR 4,416 958 339010308 706 155 339010309 1,618 317 339010310 949 225 339010311 1,143 261 KANDIARI TC 16,868 3151 GADANO 939 147 339010415 939 147 Page 1 of 53 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (KHAIRPUR DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH KANDIARI 4,447 812 339010401 1,145 217 339010402 1,069 192 339010403 1,595 281 339010404 638 122 NINDHERO 7,161 1380 339010405 962 143 339010406 1,002 185 339010407 1,052 222 339010408 1,327 280 339010409 997 221 339010410 1,157 198 339010416 664 131 PALYO LASHARI 641 135 339010411 641 135 SAHTO 1,381 271 339010412 -

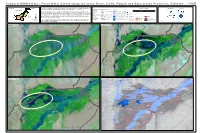

Temporal MODIS Data

21 August 2010 FL-2010-000141-PAK Te m p o r a l M O D I S D a t a - F l o o d Wa t e r E x t e n t a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n Version 1.0 Index map CHINA This map shows MODIS Terra / Aqua changes in flood water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: and provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 12 to August 21, 2010. Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Legend 0 20 40 80 AFGHANISTAN Resolution : 250m Satellite data clearly shows continous increase in flood water extent from August 12 to 21 for the Usta Mohammad Image date : August 12, 17 and 212010 Pre-Flood River Line (2009) ® Kilometres Sub-division and neighbouring Tehsils. Result show that the flood extent is continously increasing during the last 10 days Source : NASA q Airport Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) Flood Water extent (Aug 17) as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. v® Heliport PAKISTAN In the Punjab provinces flood has partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Tibba, Faizpur, Baseline Imagery : MODIS Aqua Aug 21, 2010 Flood Water extent (Aug 18) Isanwali, Mulana)as. -

Invitation to Bid (ITB) for the Above-Referenced Subject

INVITATION TO BID Media Buying for Civic Education Awareness Campaign Strengthening Electoral and Legislative Processes (SELP) ITB/UNDP/ECP/2014/001 United Nations Development Programme November, 2014 1 Section 1. Letter of Invitation Islamabad November 6, 2014 Media Buying for Civic Education Awareness Campaign Dear Sir, The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) hereby invites you to submit a Bid to this Invitation to Bid (ITB) for the above-referenced subject. This ITB includes the following documents: Section 1 – This Letter of Invitation Section 2 – Instructions to Bidders (including Data Sheet) Section 3 – Terms of Reference Section 4 – Bid Submission Form Section 5 – Documents Establishing the Eligibility and Qualifications of the Bidder Section 6 – Technical Bid Form Section 7 – Price Schedule Form Section 8 – UNDP General Terms & Conditions Your offer, comprising of a Technical Bid and Price Schedule, in separate sealed envelopes, should be submitted in accordance with Section 2. United Nations Development Programme 6th Floor, Serena Business Complex, Sector G-5, Khaban-e-Suharwardy, Islamabad. Ali Raza Shah – Procurement Officer A pre-bid conference will be held on 13 November 2014 at 1500 hours in UNDP office situated at 6th Floor Serena Business Complex, Khayaban e Suharwardy, Islamabad. The bidders who wish to attend the pre-bid conference are kindly requested to send the name, NIC number and company name to Mr. Ali Raza Shah, email: [email protected] prior to 11th November 2014 by 1500 hours in order to obtain necessary security clearance. No bidder will be allowed to take part without security clearance. Important note: Please put the subject and reference Number of the ITB in the subject line.