Heat Illness Prevention Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, Heat, and Entropy

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 4: 09.16.05 Temperature, heat, and entropy Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� State functions ..............................................................................................................................................................................2� Path dependent variables: heat and work..................................................................................................................................2� DEFINING TEMPERATURE ...................................................................................................................................................................4� The zeroth law of thermodynamics .............................................................................................................................................4� The absolute temperature scale ..................................................................................................................................................5� CONSEQUENCES OF THE RELATION BETWEEN TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND ENTROPY: HEAT CAPACITY .......................................6� The difference between heat and temperature ...........................................................................................................................6� Defining heat capacity.................................................................................................................................................................6� -

HEAT and TEMPERATURE Heat Is a Type of ENERGY. When Absorbed

HEAT AND TEMPERATURE Heat is a type of ENERGY. When absorbed by a substance, heat causes inter-particle bonds to weaken and break which leads to a change of state (solid to liquid for example). Heat causing a phase change is NOT sufficient to cause an increase in temperature. Heat also causes an increase of kinetic energy (motion, friction) of the particles in a substance. This WILL cause an increase in TEMPERATURE. Temperature is NOT energy, only a measure of KINETIC ENERGY The reason why there is no change in temperature at a phase change is because the substance is using the heat only to change the way the particles interact (“stick together”). There is no increase in the particle motion and hence no rise in temperature. THERMAL ENERGY is one type of INTERNAL ENERGY possessed by an object. It is the KINETIC ENERGY component of the object’s internal energy. When thermal energy is transferred from a hot to a cold body, the term HEAT is used to describe the transferred energy. The hot body will decrease in temperature and hence in thermal energy. The cold body will increase in temperature and hence in thermal energy. Temperature Scales: The K scale is the absolute temperature scale. The lowest K temperature, 0 K, is absolute zero, the temperature at which an object possesses no thermal energy. The Celsius scale is based upon the melting point and boiling point of water at 1 atm pressure (0, 100o C) K = oC + 273.13 UNITS OF HEAT ENERGY The unit of heat energy we will use in this lesson is called the JOULE (J). -

Heat Energy a Science A–Z Physical Series Word Count: 1,324 Heat Energy

Heat Energy A Science A–Z Physical Series Word Count: 1,324 Heat Energy Written by Felicia Brown Visit www.sciencea-z.com www.sciencea-z.com KEY ELEMENTS USED IN THIS BOOK The Big Idea: One of the most important types of energy on Earth is heat energy. A great deal of heat energy comes from the Sun’s light Heat Energy hitting Earth. Other sources include geothermal energy, friction, and even living things. Heat energy is the driving force behind everything we do. This energy gives us the ability to run, dance, sing, and play. We also use heat energy to warm our homes, cook our food, power our vehicles, and create electricity. Key words: cold, conduction, conductor, convection, energy, evaporate, fire, friction, fuel, gas, geothermal heat, geyser, heat energy, hot, insulation, insulator, lightning, liquid, matter, particles, radiate, radiant energy, solid, Sun, temperature, thermometer, transfer, volcano Key comprehension skill: Cause and effect Other suitable comprehension skills: Compare and contrast; classify information; main idea and details; identify facts; elements of a genre; interpret graphs, charts, and diagram Key reading strategy: Connect to prior knowledge Other suitable reading strategies: Ask and answer questions; summarize; visualize; using a table of contents and headings; using a glossary and bold terms Photo Credits: Front cover: © iStockphoto.com/Julien Grondin; back cover, page 5: © iStockphoto.com/ Arpad Benedek; title page, page 20 (top): © iStockphoto.com/Anna Ziska; pages 3, 9, 20 (bottom): © Jupiterimages Corporation; -

TEMPERATURE, HEAT, and SPECIFIC HEAT INTRODUCTION Temperature and Heat Are Two Topics That Are Often Confused

TEMPERATURE, HEAT, AND SPECIFIC HEAT INTRODUCTION Temperature and heat are two topics that are often confused. Temperature measures how hot or cold an object is. Commonly this is measured with the aid of a thermometer even though other devices such as thermocouples and pyrometers are also used. Temperature is an intensive property; it does not depend on the amount of material present. In scientific work, temperature is most commonly expressed in units of degrees Celsius. On this scale the freezing point of water is 0oC and its boiling point is 100oC. Heat is a form of energy and is a phenomenon that has its origin in the motion of particles that make up a substance. Heat is an extensive property. The unit of heat in the metric system is called the calorie (cal). One calorie is defined as the amount of heat necessary to raise 1 gram of water by 1oC. This means that if you wish to raise 7 g of water by 4oC, (4)(7) = 28 cal would be required. A somewhat larger unit than the calorie is the kilocalorie (kcal) which equals 1000 cal. The definition of the calorie was made in reference to a particular substance, namely water. It takes 1 cal to raise the temperature of 1 g of water by 1oC. Does this imply perhaps that the amount of heat energy necessary to raise 1 g of other substances by 1oC is not equal to 1 cal? Experimentally we indeed find this to be true. In the modern system of international units heat is expressed in joules and kilojoules. -

Lecture 6: Entropy

Matthew Schwartz Statistical Mechanics, Spring 2019 Lecture 6: Entropy 1 Introduction In this lecture, we discuss many ways to think about entropy. The most important and most famous property of entropy is that it never decreases Stot > 0 (1) Here, Stot means the change in entropy of a system plus the change in entropy of the surroundings. This is the second law of thermodynamics that we met in the previous lecture. There's a great quote from Sir Arthur Eddington from 1927 summarizing the importance of the second law: If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equationsthen so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observationwell these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of ther- modynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. Another possibly relevant quote, from the introduction to the statistical mechanics book by David Goodstein: Ludwig Boltzmann who spent much of his life studying statistical mechanics, died in 1906, by his own hand. Paul Ehrenfest, carrying on the work, died similarly in 1933. Now it is our turn to study statistical mechanics. There are many ways to dene entropy. All of them are equivalent, although it can be hard to see. In this lecture we will compare and contrast dierent denitions, building up intuition for how to think about entropy in dierent contexts. The original denition of entropy, due to Clausius, was thermodynamic. -

Symptoms of Heat- Related Illness How to Protect Your

BE PREPARED FOR EXTREME HEAT Extreme heat often results in the highest annual number of deaths among all weather-related disasters. FEMA V-1004/June 2018 In most of the U.S., extreme heat is a long period (2 to 3 days) of high heat and humidity with temperatures above 90 degrees. Greater risk Can happen anywhere Humidity increases the feeling of heat as measured by a heat index IF YOU ARE UNDER AN EXTREME HEAT WARNING Check on family members Find air conditioning, if possible. and neighbors. Avoid strenuous activities. Drink plenty of fluids. Watch for heat cramps, heat Watch for heat illness. exhaustion, and heat stroke. Wear light clothing. Never leave people or pets in a closed car. HOW TO STAY SAFE WHEN EXTREME HEAT THREATENS Prepare Be Safe Recognize NOW DURING +RESPOND Find places in your community where Never leave a child, adult, or animal Know the signs and ways to treat you can go to get cool. alone inside a vehicle on a warm day. heat-related illness. Try to keep your home cool: Find places with air conditioning. Heat Cramps Libraries, shopping malls, and • Signs: Muscle pains or spasms in • Cover windows with drapes community centers can provide a cool the stomach, arms, or legs. or shades. place to take a break from the heat. • Actions: Go to a cooler location. • Weather-strip doors and Wear a If you’re outside, find shade. Remove excess clothing. Take windows. hat wide enough to protect your face. sips of cool sports drinks with salt and sugar. Get medical help if • Use window reflectors such as Wear loose, lightweight, light- cramps last more than an hour. -

Module P7.4 Specific Heat, Latent Heat and Entropy

FLEXIBLE LEARNING APPROACH TO PHYSICS Module P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy 1 Opening items 4 PVT-surfaces and changes of phase 1.1 Module introduction 4.1 The critical point 1.2 Fast track questions 4.2 The triple point 1.3 Ready to study? 4.3 The Clausius–Clapeyron equation 2 Heating solids and liquids 5 Entropy and the second law of thermodynamics 2.1 Heat, work and internal energy 5.1 The second law of thermodynamics 2.2 Changes of temperature: specific heat 5.2 Entropy: a function of state 2.3 Changes of phase: latent heat 5.3 The principle of entropy increase 2.4 Measuring specific heats and latent heats 5.4 The irreversibility of nature 3 Heating gases 6 Closing items 3.1 Ideal gases 6.1 Module summary 3.2 Principal specific heats: monatomic ideal gases 6.2 Achievements 3.3 Principal specific heats: other gases 6.3 Exit test 3.4 Isothermal and adiabatic processes Exit module FLAP P7.4 Specific heat, latent heat and entropy COPYRIGHT © 1998 THE OPEN UNIVERSITY S570 V1.1 1 Opening items 1.1 Module introduction What happens when a substance is heated? Its temperature may rise; it may melt or evaporate; it may expand and do work1—1the net effect of the heating depends on the conditions under which the heating takes place. In this module we discuss the heating of solids, liquids and gases under a variety of conditions. We also look more generally at the problem of converting heat into useful work, and the related issue of the irreversibility of many natural processes. -

3. Energy, Heat, and Work

3. Energy, Heat, and Work 3.1. Energy 3.2. Potential and Kinetic Energy 3.3. Internal Energy 3.4. Relatively Effects 3.5. Heat 3.6. Work 3.7. Notation and Sign Convention In these Lecture Notes we examine the basis of thermodynamics – fundamental definitions and equations for energy, heat, and work. 3-1. Energy. Two of man's earliest observations was that: 1)useful work could be accomplished by exerting a force through a distance and that the product of force and distance was proportional to the expended effort, and 2)heat could be ‘felt’ in when close or in contact with a warm body. There were many explanations for this second observation including that of invisible particles traveling through space1. It was not until the early beginnings of modern science and molecular theory that scientists discovered a true physical understanding of ‘heat flow’. It was later that a few notable individuals, including James Prescott Joule, discovered through experiment that work and heat were the same phenomenon and that this phenomenon was energy: Energy is the capacity, either latent or apparent, to exert a force through a distance. The presence of energy is indicated by the macroscopic characteristics of the physical or chemical structure of matter such as its pressure, density, or temperature - properties of matter. The concept of hot versus cold arose in the distant past as a consequence of man's sense of touch or feel. Observations show that, when a hot and a cold substance are placed together, the hot substance gets colder as the cold substance gets hotter. -

Thermodynamic Temperature

Thermodynamic temperature Thermodynamic temperature is the absolute measure 1 Overview of temperature and is one of the principal parameters of thermodynamics. Temperature is a measure of the random submicroscopic Thermodynamic temperature is defined by the third law motions and vibrations of the particle constituents of of thermodynamics in which the theoretically lowest tem- matter. These motions comprise the internal energy of perature is the null or zero point. At this point, absolute a substance. More specifically, the thermodynamic tem- zero, the particle constituents of matter have minimal perature of any bulk quantity of matter is the measure motion and can become no colder.[1][2] In the quantum- of the average kinetic energy per classical (i.e., non- mechanical description, matter at absolute zero is in its quantum) degree of freedom of its constituent particles. ground state, which is its state of lowest energy. Thermo- “Translational motions” are almost always in the classical dynamic temperature is often also called absolute tem- regime. Translational motions are ordinary, whole-body perature, for two reasons: one, proposed by Kelvin, that movements in three-dimensional space in which particles it does not depend on the properties of a particular mate- move about and exchange energy in collisions. Figure 1 rial; two that it refers to an absolute zero according to the below shows translational motion in gases; Figure 4 be- properties of the ideal gas. low shows translational motion in solids. Thermodynamic temperature’s null point, absolute zero, is the temperature The International System of Units specifies a particular at which the particle constituents of matter are as close as scale for thermodynamic temperature. -

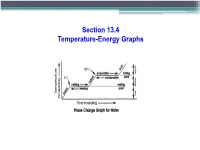

Section 13.4 Temperature-Energy Graphs Temperature-Energy Graphs

Section 13.4 Temperature-Energy Graphs Temperature-Energy Graphs A temperature-energy graph shows the energy and temperature changes as water turns from a solid, ice, to a liquid, water, and finally to a gas, water vapor. Water Phase Change Graph F D 100 E gas liquid Temperature º C. º Temperature B 0 C solid A Heat (thermal energy) Phase Change Diagram – Flat Line • Anytime there is a flat line on a temp-energy graph, a phase change is occurring. Water Phase Change Graph F D condensing 100 boiling E Temperature º C. º Temperature B freezing 0 melting C A Heat (thermal energy) Temperature-Energy Graphs Calculating Energy of a Phase Change Heat of Fusion (solid - liquid) Heat of Fusion: The amount of energy absorbed or released when a substance melts or freezes. • Symbol: LF • The LF for water is 334 J/g • This is the quantity of heat that must be absorbed by each gram of ice at 0°C to convert it to water at 0°C • This is the quantity of heat that must be released from each gram of water at 0°C to convert it to ice at 0°C Heat of Fusion (solid - liquid) Heat of Fusion: • Varies for different substances • All the energy is used to increase the potential energy of the particles. (Break bonds) • Average kinetic energy doesn’t change Heat of Fusion (solid - liquid) Heat of Fusion: Q = m·Lf Heat of Fusion Heat Mass Heat of Vaporization (liquid – gas) Heat of Vaporization: The amount of energy absorbed or released when a substance boils or condenses. -

Discipline in Thermodynamics

energies Perspective Discipline in Thermodynamics Adrian Bejan Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0300, USA; [email protected] Received: 24 April 2020; Accepted: 11 May 2020; Published: 15 May 2020 Abstract: Thermodynamics is a discipline, with unambiguous concepts, words, laws and usefulness. Today it is in danger of becoming a Tower of Babel. Its key words are being pasted brazenly on new concepts, to promote them with no respect for their proper meaning. In this brief Perspective, I outline a few steps to correct our difficult situation. Keywords: thermodynamics; discipline; misunderstandings; disorder; entropy; second law; false science; false publishing 1. Our Difficult Situation Thermodynamics used to be brief, simple and unambiguous. Today, thermodynamics is in a difficult situation because of the confusion and gibberish that permeate through scientific publications, popular science, journalism, and public conversations. Thermodynamics, entropy, and similar names are pasted brazenly on new concepts in order to promote them, without respect for their proper meaning. Thermodynamics is a discipline, a body of knowledge with unambiguous concepts, words, rules and promise. Recently, I made attempts to clarify our difficult situation [1–4], so here are the main ideas: The thermodynamics that in the 1850s joined science serves now as a pillar for the broadest tent, which is physics. From Carnot, Rankine, Clausius, and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) came not one but two laws: the law of energy conservation (the first law) and the law of irreversibility (the second law). The success of the new science has been truly monumental, from steam engines and power plants of all kinds, to electric power in every outlet, refrigeration, air conditioning, transportation, and fast communication today. -

Prevent Heat Illness at Work Poster

Prevent Heat Illness at Work Outdoor and indoor heat exposure can be dangerous. Ways to Protect Yourself and Others Ease into Work. Nearly 3 out of 4 fatalities from heat illness happen during the first week of work. 100% New and returning workers need to build tolerance to heat (acclimatize) and take frequent breaks. 20% Follow the 20% Rule. On the first day, work no more than 20% of the shift’s duration at full intensity in the heat. Increase the duration of time at full intensity by no more than 20% a day until workers are used to working in the heat. MON TUE WED THU FRI Drink Cool Water Dress for the Heat Drink cool water even if you are not thirsty — at least Wear a hat and light-colored, loose-fitting, and 1 cup every 20 minutes. breathable clothing if possible. Take Rest Breaks Watch Out for Each Other Take enough time to recover from heat given the Monitor yourself and others for signs of temperature, humidity, and conditions. heat illness. If Wearing a Face Covering Find Shade or a Cool Area Change your face covering if it gets wet or soiled. Take breaks in a designated shady or cool location. Verbally check on others frequently. First Aid for Heat Illness The following are signs of a medical emergency! Abnormal thinking or behavior ?? ? ? ? ? Slurred speech Seizures 9-1-1 Loss of consciousness 1 CALL 911 IMMEDIATELY 2 COOL THE WORKER RIGHT AWAY WITH WATER OR ICE 3 STAY WITH THE WORKER UNTIL HELP ARRIVES Watch for any other signs of heat illness and act quickly.