A Tale of Resilience of Kashmiri Pandits with Special Reference to Shikara: the Untold Story of Pandits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Detail of Land Looser Appointments

F.No District Name of land owner Claimant for job Remarks S.No 1 1 Baramulla Ab Jabar Mir Tahir Jabbar Appointment given 2 2 Baramulla Habir Dar Tariq Ahmed Dar Appointment given 3 3 Baramulla Ab Qayoom Kimani Ummul Mudal Appointment given 4 4 Baramulla Ahad S/o Khalil Tantray Hilal Ahmed Appointment given 5 5 Baramulla Sharief-u-dine Mudasir Sharief Appointment given 6 Baramulla Sirajudin,ShaffudunBashir Umar Bashir s/o Appointment given 6 Ahmed etc. Bashir Ahmad 7 7 Baramulla Bashir Ahmed Javid Ahmad Appointment given 8 8 Baramulla Bashir Ah. Naikoo Tahira Bashir Appointment given 9 10 Baramulla Gh Qadir Guroo Hilal Ahmed Appointment given 10 11 Baramulla Mohmud Md. Yousuf Appointment given 11 12 Baramulla Gh Mohd. Bashir Ah.Ganie Appointment given 12 14 Baramulla Gh Ahmed Tantary Ab. Hamid Tantry Appointment given 23 Baramulla Ramzan Manzoor Ahmed Appointment given 13 Rather 27 Baramulla Jawahar Lal Dhar S/O Sahil Dhar Appointment given 14 Mahesh Nath 15 36 Pulwama Ab Hamid Dar Adil Hamid Dar Appointment given 16 38 Pulwama Subhan Jahangir Ahmed Appointment given 39 Pulwama Gh Nabi S/o Lassa Lone Shabir Ahmad Lone Appointment given 17 18 40 Pulwama Gh Ahmad Nisar Ahmed Appointment given 19 42 Pulwama Gh. Nabi Bhat Shabir Ahmad Bhat Appointment given 20 43 Pulwama Shaban Riyaz Ahmad Dar Appointment given 21 45 Pulwama Bashir Ah. Ganie Bashir Ah. Ganie Appointment given 22 46 Pulwama Gh Hassan Dar Zahoor Ahmed Dar Appointment given 47 Pulwama Jameela Akther Kurshid Ahmad Appointment given 23 Kuchay 24 48 Pulwama Gh Hassan Sheikh Tawseef Hassan Appointment given 25 49 Pulwama Md Abdullah Sheikh Mehraj-u-Din Appointment given 26 50 Pulwama Aziz Mir S/o Samad Mir Gulzar Ahmed Appointment given 27 51 Pulwama Rehman Hajam Ab. -

Pt. Bansi Dhar Nehru Was Born in 1843 at Delhi

The firm foundation of the Mughal empire in India was laid by a Uzbek Mongol warrior Zahiruddin Mohammand Babar, who was born in 1483 in a tiny village Andijan on the border of Uzbekistan and Krigistan after defeating the Sultan of Delhi Ibrahim Lodi in the battle of Panipat which took place in 1526, The Rajputs soon thereafter under the command of Rana Sanga challenged the authority of Babar, but were badly routed in the battle of Khanwa near Agra on 16th March, 1527. Babar with a big army then went upto Bihar to crush the revolt of Afgan chieftains and on the way his commander in chief Mir Baqi destroyed the ancient Ram Temple at Ayodhya and built a mosque at that spot in 1528. Babar than returned back to Agra where he died on 26th December 1530 dur t o injuries received in the battle with Afgans in 1529 at the Ghaghra’s is basin in Bihar. After Babar’s death his son Nasiruddin Humanyu ascended the throne, but he had to fight relentless battels with various rebellious chieftains for fight long years. The disgruntled Afghan chieftains found Sher Shah Suri as an able commander who defeated Humanyu in the battle of Chausa in Bihar and assumed power at Delhi in 1543. Sher Shah Suri died on 22nd May 1545 due to injuries suffered in a blast after which the Afghan power disintegrated. Hymanyu then taking full advantage of this fluid political situation again came back to India with reinforcements from Iran and reoccupied the throne at Delhi after defeating Adil Shah in the second battle of Panipat in 1555. -

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland

"Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Author(s): Haley Duschinski Source: International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Apr., 2008), pp. 41-64 Published by: Springer Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40343840 Accessed: 12-01-2020 07:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Journal of Hindu Studies This content downloaded from 134.114.107.39 on Sun, 12 Jan 2020 07:34:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Survival Is Now Our Politics": Kashmiri Hindu Community Identity and the Politics of Homeland Haley Duschinski Kashmiri Hindus are a numerically small yet historically privileged cultural and religious community in the Muslim- majority region of Kashmir Valley in Jammu and Kashmir State in India. They all belong to the same caste of Sarasvat Brahmanas known as Pandits. In 1989-90, the majority of Kashmiri Hindus living in Kashmir Valley fled their homes at the onset of conflict in the region, resettling in towns and cities throughout India while awaiting an opportunity to return to their homeland. -

179 Reinterpreting Afghan Rule in Kashmir Dr. Aushaq Hussain Dar

The Communications Vol.27. No (01) ISSN: 0975-6558 Reinterpreting Afghan Rule in Kashmir Dr. Aushaq Hussain Dar Assistant Professor Govt. Degree College Pulwama Mr. Ali Mohammad Shah Sr. Assistant Professor GDC Pulwama Abstract: In 1753, Afghans established their political authority in Kashmir. Afhan rule has been painted with dark colours by a section of Pandit chroniclers. These Pandit chroniclers wrote in the beginning of Sikh rule and projected Afghans as religious fanatics and ruthless masters who persecuted Hindu community by subjecting them to heavy taxation and other humiliating practices. Sikh rule on the other hand was hailed as rule of deliverance by these chroniclers. This was done for the purpose of gaining sympathy of new establishment. True, Afghans were tough masters who ruthlessly exploited the people of Kashmir but we argue that Afghan governors in Kashmir were more guided by lust for power and tribal codes than their religion. Besides, Afghan state was not different than medieval imperial states which aimed at ruthless exploitation of peripheries and awarded exemplary punishments to rebels. The sufferings during the period under reference should be viewed as inclusive experience of all sections of society instead of a particular community. Key words: Afghan, Pandit, Kashmiri, Medieval, community Introduction: Punjab was invaded by Ahmad Shah Abdali third time in 1752. He defeated governor Muin-ul- Muluk, and spread terror over the whole of Northern India. At this time Kashmir was governed by Abdul Qasim Khan. He usurped the throne by displacing Mir Muqim Kanth. There upon disgruntled Kashmiri leaders, Mir Muqim Kanth and Khawaja Zahir u Din Didamiri sent their agents to Ahmad Shah Abdali and invited him to invade Kashmir. -

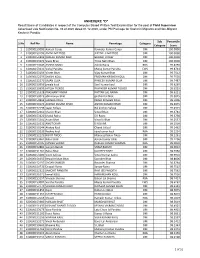

ANNEXURE "F" Result/Score of Candidates in Respect of the Computer Based Written Test/Examination for the Post of Depot Assistant Advertised Vide Notification No

ANNEXURE "F" Result/Score of Candidates in respect of the Computer Based Written Test/Examination for the post of Depot Assistant Advertised vide Notification No. 03 of 2020 dated 01.12.2020, under PM Package for Kashmiri Migrants and Non-Migrant Kashmiri Pandits: Sub Percentile S.No Roll No Name Parentage Category Category Score 1 410000200218 Akshay Koul Chand Ji Koul OM 100.0000 2 410000201850 Lalit Anjum Pradiman Krishan Kher OM 100.0000 3 410000202831 PRASHANT RAINA RATTAN LAL RAINA OM 100.0000 4 410000203858 Sagar Safaya Bal krishen Safaya OM 100.0000 5 410000204479 Shivam Pandita BANSI LAL PANDITA OM 100.0000 6 410000204980 Sunjam Bakshi SHAM BAKSHI OM 100.0000 7 410000201740 Kewal Krishan Bhat Surinder Bhat OM 99.8804 8 410000203289 RAKESH KUMAR KAW BHARAT JI KAW OM 99.8800 9 410000202241 Monika Jamwal Harjeet Singh OM 99.8791 10 410000205443 Vinayak Sharma Behari Lal Sharma RBA 99.8791 11 410000200282 AMAN MATTOO JEETAN JI MATTOO OM 99.8783 12 410000202592 NISHANT BHARTI ZADOO KESHAV VIKRAM ZADOO OM 99.8783 13 410000201170 Danish Pandita Ajay Pandita RBA 99.7608 14 420000205761 Aryan Bhat Vinod Ji Bhat OM 99.7608 15 410000201544 Ishan Koul Ashok Kumar Koul OM 99.7599 16 410000200875 ASHISH RAINA Ashok Raina RBA 99.7582 17 410000203597 Rockey koul vijay kumar koul RBA 99.7582 18 410000202080 meenakshi ravinder kumar OM 99.7567 19 410000203989 SAKSHI KOUL PRIDMAN KRISHEN KOUL OM 99.7567 20 410000200608 Ankush Raina Avtar Krishen Raina RBA 99.6399 21 410000200309 Ameesha Kardar Kanaya Lal OM 99.6372 22 410000203167 Rahul Tickoo -

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material)

Afghan Rule in Kashmir (A Critical Review of Source Material) Dissertation submitted to the University of Kashmir for the Award of the Degree of Master of Philosophy (M. Phil) In Department of History By Rouf Ahmad Mir Under the Supervision of Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Associate Professor) Post Graduate Department of History University Of Kashmir Hazratbal, Srinagar-6 2011 Post Graduate Department of History University of KashmirSrinagar-190006 (NAAC Accredited Grade “A”) CERTIFICATE This is to acknowledge that this dissertation, entitled Afghan Rule in Kashmir: A Critical Review of Source Material, is an original work by Rouf Ahmad, Scholar, Department of History, University of Kashmir, under my supervision, for the award of Pre-Doctoral Degree (M.Phil). He has fulfilled the entire statutory requirement for submission of the dissertation. Dr. Farooq Fayaz (Supervisor) Associate Professor Post Graduate Department of History University of Kashmir Srinagar-190006 Acknowledgement I am thankful to almighty Allah, our lord, Cherisher and sustainer. At the completion of this academic venture, it is my pleasure that I have an opportunity to express my gratitude to all those who have helped and encouraged me all the way. I express my gratitude and reverence to my teacher and guide Dr. Farooq Fayaz Associate Professor, Department of History University of Kashmir, for his generosity, supervision and constant guidance throughout the course of this study. It is with deep sense of gratitude and respect that I express my thanks to Prof. G. R. Jan (Professor of Persian) Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, my co-guide for his unique and inspiring guidance. -

The Brahmins of Kashmir

September 1991, Michael Witzel THE BRAHMINS OF KASHMIR vedai +aagai1 padakramayutair vedåntasiddhåntakais tarkavyåkaraai puråapahanair mantrai aagågamai ... pauråaśrutitarkaśåstranicayai ki cågnihotråkitair viprair dhyånatapojapådiniratai snånårcanådyutsukai ... kåśmīrabhūr uttamå || (Råjataragiī of Jonaråja, B 747) With the Vedas, the six appendices, with the Pada and Krama (texts), with Vedånta and Siddhånta, logic and grammar, Puråa recitation, with (Tantric) Mantras and the six traditional sects ... with its masses of Puråic, Vedic (śruti) and logic disciplines (tarkaśåstra), and, moreover, marked by Agnihotrins, with Brahmins devoted to meditation, asceticism, recitation and so on, and zealeaously engaged with ablutions, worship, and the like, ... the land of Kashmir is the best. Introduction The Kashmiri Brahmins, usually called Paits, constitute one single group, the Kåśmīra Bråhmaas, without any real subdivisions. They form, according to Bühler,2 the first Indologist to visit the Valley, one unified community: they 'interdine' (annavyavahåra) and they also teach each other (vidyåvyavahåra, vidyåsambandha). But not all of them intermarry (kanyåvyavahåra, yonisambandha), which is the real test of belonging or not belonging to a single community. This is confirmed by Lawrence,3 who distinguishes "the astrologer class (Jotish), the priest class (Guru or Båchabat) and the working class (Kårkun). The priest class do not intermarry with either of the other classes. But the Jotish and Kårkun intermarry. The Jotish Pundits are learned in the Shastras and expound them to the Hindus, and they draw up the calendars in which prophecies are made about the events of the coming year. The priest class perform the rites and ceremonies of the Hindu religion. The vast majority of the Pandits belong to the Kårkun class and have usually made their livelihood in the employment of the state." This division is believed to have taken place after the country turned to Islam in the fourtheenth century, and especially after the initial persecution of Brahmins at around 1400 A.D. -

Innovations, Number 64 April 2021

Innovations, Number 64 April 2021 Innovations Content available on Google Scholar www.journal-innovations.com Exodus of Kashmiri Pandits a Review 1. Mohan Lal Research Scholar (Sociology), Lovely Professional University 2. Dr. Debahuti Panigrah Asstt. Professor, Deptt. of Sociology, Lovely Professional University Abstract Kashmiri Pandits, a small religious minority community in Kashmir's valley of which exodus began in January 1990 in which they were forcibly driven out of their homeland in Kashmir. As a result, their homes were set on fire, temples were burnt, and hundreds of people were killed. Kashmiri Pandits then decided to leave the valley and have been staying in refugee camps in various parts of the country, especially in Jammu. The government has taken a number of steps to help struggling families, as part of a larger strategy whereby those who have moved will eventually return to the valley. The government has also been providing assistance to uprooted families in Jammu district's camp and non-camp areas who have lost their source of income due to migration. Since then, Kashmiri Pandits have not returned to their homeland, and a return is still a distant hope for them. This paper aims to know the causes of exodus of Kashmiri Pandit, to know the problem faced by the Kashmiri Pandit, measure taken by the government for rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandit and to examine their present status. It also aims to find out the causes and effect of exodus and the rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits in the Kashmir valley as well as the government's various decisions in their favou r. -

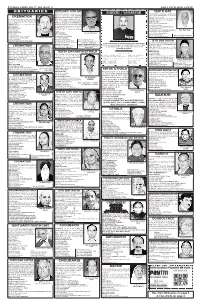

Page2.Qxd (Page 2)

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 2018 (PAGE 2) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU OBITUARIES OBITUARY/ 10TH DAY TENTH DAY With profound grief and sorrow, we regret to BARKHI / VAHARVAR With profound grief and sorrow, we inform the sad inform the sad demise of Sh Janki Nath demise of Smt. Ram Pyari W/o Sh. Inder Dass CREMATION Raina S/o Lt Gopi Nath Raina, originally res- Dalotra R/o Gharota Jammu. Tenth Day will be performed on 1st of March, 2018 With profound grief and sorrow, we inform the sad demise ident of Avil, Kulgam Kashmir A/P Sec 2, of our beloved Sh. Jagmohan Singh Sumbria S/o Late H.No 5-C, Sharda Colony Patoli Brahmna, (Thursday), 2 PM at their residence, Gharota. GRIEF STRICKEN Sh. Janak Singh Sumbria R/o Sec D Sainik Colony Barnaie on 23.02.2018. His 10th Day will be Extension Lane No.1. Sh. Inder Dass Dalotra -Husband performed on March 3, 2018 at Akhnoor Ghat. CREMATION will take place on 27/02/2018 at 3 PM at Son & Daughter-in-law Mandal (Purmandal) Assembly will be held at residence at 11.30 am. Smt. Mamta Devi & Sh. Dwarka Nath Dalotra GRIEF STRICKEN The Mourning will be held at our residence at Smt. Sandhya Devi (Wife) Daughter & Son-in-law Ranvijay Singh (Son) H.No 5-C, Sec 2, Sharda Colony Patoli Smt. Manisha Devi & Sh. Parshotam Lal Sagotra Smt. Ram Pyari Suryadev Singh (Son) Brahmna. Grand Daughter & Grand Son-in-law Brother and Sister in law GRIEF STRICKEN Sh Janki Nath Raina Arti Devi & Rajesh Kumar Sagotra Sh.Randhir Singh Smt Janak Rani -Wife Rahul Dalotra -Grand Son Smt. -

Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmir

Aryan Saraswat Brahmins Of Kashmeere {Kashmir} Through Two Millenniums Of Triumph, Search Of Identity, Conversion Trauma’s, Exodus’s To Pandit Bhawani { 18th/ 19th Century } Contents Part I : Curiosity For Past - Aryan Saraswat Brahmin Honorific Gotra - Genesis, Orientation, Proliferation – Dattatreya’ Gotra Part II : Advent Of Islam By Preachers And Helped By Then Rulers- T yranny - First Exodus 15th Century Part III : Saraswat Bhatta’s And Surnames Part IV : Surname Roots From Shakta Worship - Re- return And Rebirth Gratus Shriya Bhatta {Shri Bhat } - Conversions and Re-Exodus - Stars Rise Under Moghuls : Pandit Honorific Part V : Controversy Pandit Honorific – Under Later Moghuls Afghan’s And Later Dogra Rule ; Star Pandit’s : Narain And Bhawani PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Aryan Saraswat Brahmins Of Kashmeere {Kashmir} Through Two Millenniums Of Triumph, Search Of Identity, Conversion Trauma’s, Exodus’s To Pandit Bhawani { 18th/ 19th Century } - Brigadier Rattan Kaul {The article intends to remind our Gen X of triumphs, traumas, achievements, exoduses and survival of Aryan Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmeere {Kashmir} during the past two millenniums. The inspirational effort goes to Puja, who enters the portals of family of Bhawani Kaul of Kashmeere’s, becomes part of the community and welcomed to philosophy and fold of Aryan Saraswat Brahmins of Kashmeere {Kashmir}, like Queen Yasomati {300 BC} and Queen Ahala {13th Century- who built Ahalamatha Math, present-day ‘Gund Ahlamar’, close to the roots of Bhawani’s descendants }- Author} Part I – Curiosity For Past - Aryan Saraswat Brahmin Honorific - Gotra Genesis, Orientation, Proliferation - Dattatreya Gotra Curiosity For Past. These are not the triumphs and travails of a particular Aryan Saraswat Brahmin of Kashmeere {Kashmir}, commonly referred now as Kashmiri {Kashmeeri} Pandit, but transition of a community through two millenniums of religious philosophies, search of identity, Gotra orientation, honorific’s Bhatta and Pandit and selective surnames. -

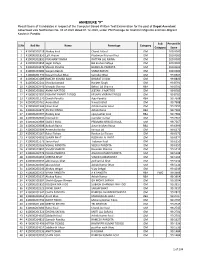

ANNEXURE "D" Result/Score of Candidates in Respect of the Computer Based Written Test/Examination for the Post of Field Supervisor Advertised Vide Notification No

ANNEXURE "D" Result/Score of Candidates in respect of the Computer Based Written Test/Examination for the post of Field Supervisor Advertised vide Notification No. 03 of 2020 dated 01.12.2020, under PM Package for Kashmiri Migrants and Non-Migrant Kashmiri Pandits: Sub Percentile S.No Roll No Name Parentage Category Category Score 1 310000150003 Aakash Ganju Ravinder Kumar Ganju OM 100.0000 2 310000150195 AMAN MATTOO JEETAN JI MATTOO OM 100.0000 3 310000151893 RAKESH KUMAR KAW BHARAT JI KAW OM 100.0000 4 310000153272 Vivek Bhan Trilok Nath Bhan OM 100.0000 5 310000150545 ASHISH RAINA Ashok Raina RBA 99.8756 6 310000153231 Vishal Pandita Manoj kumar Pandita EWS 99.8744 7 310000153159 Vineet Bhat Vijay Kumar Bhat OM 99.7512 8 310000152293 SAKSHI KOUL PRIDMAN KRISHEN KOUL OM 99.7503 9 310000152270 SAJAN GOJA RAMESH KUMAR GOJA OM 99.7487 10 310000150956 jawala koul Sunil kumar koul OM 99.6269 11 310000150899 HITESH TICKOO RAVINDER KUMAR TICKOO OM 99.6255 12 310000151628 PRASHANT RAINA RATTAN LAL RAINA OM 99.6231 13 310000150023 abhimanyu bhat girdhari lal bhat OM 99.5025 14 310000150869 HARSHA KOUL INDER KRISHEN KOUL OM 99.5006 15 310000150173 AKSHAY KUMAR DHAR ASHOK KUMAR DHAR OM 99.4975 16 310000152196 Sagar Safaya Bal krishen Safaya OM 99.4975 17 310000152466 Sharen Bhan Vinod Bhan OM 99.3781 18 320000153420 Mukul Raina S K Raina OM 99.3758 19 320000153341 Aryan Bhat Vinod Ji Bhat OM 99.2537 20 310000150332 ANKIT DHAR K N DHAR OM 99.2509 21 310000150144 Akshay Koul Chand Ji Koul OM 99.2462 22 310000152038 Rockey koul vijay kumar koul RBA -

Political Consciousness of Kashmiri Pandits in British India

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2017; 3(9): 138-144 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal Peer Reviewed Journal Political Consciousness of Kashmiri Pandits in British Refereed Journal Indexed Journal India UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 e-ISSN: 2454-6615 Nitin Chandel Nitin Chandel Abstract Research Scholar The paper describes the role of Kashmiri Pandits in political mobilization during the British spell in Department Of History India and adjusted them with the changing milieu. The main focus of analysis is on the kinds of University Of Jammu, India professional choices they made and the position of power they occupied in their individual capacity in areas far away from their home land. The article mentions the migration of Pandits sometimes forceful and economical and their adjustment in India with receptive to education and their elevation to different arena which led to formation of association and finally politicized the Pandits in India. An important part of our analysis is to understand how this Diasporas of Kashmir Pandit retained their affinity or connectivity with the community to which they originally belonged. An integral part of our analysis is also to see how the migrant Kashmiri Pandits rose to prominence and also made substantial contribution in their respective area of habitation. The work analyses the role of Kashmiri Pandits in the freedom struggle of the country and their elevation of some of them to the important post in the Indian National Congress. The article pronounces the community consciousness through reform organisation which tends to build the progression of the Pandits in diverse arenas of social stature.