The Great Fire of London 2Nd-6Th September 1666

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Days at the Inns of Court

STUDENT DAYS AT THE INNS OF COURT.* Fortescue tells us that when King John fixed the Court of Common Pleas at Westminster, the professors of the municipal law who heretofore had been scattered about the kingdom formed themselves into an aggregate body "wholly addicted to the study of the law." This body, having been excluded from Oxford and Cambridge where the civil and canon laws alone were taught, found it necessary to establish a university of its own. This it did by purchasing at various times certain houses between the City of Westminster, where the King's courts were held, and the City of London, where they could obtain their provisions. The nearest of these institutions to the City of London was the Temple. Passing through Ludgate, one came to the bridge over the Fleet Brook and continued down Fleet Street a short distance to Temple Bar where were the Middle, Inner and Outer Temples. The grounds of the Temples reached to the bank of the Thames and the barges of royalty were not infrequently seen drawn up to the landing, when kings and queens would honor the Inns with their presence at some of the elaborate revels. For at Westminster was also the Royal Palace and the Abbey, and the Thames was an easy highway from the market houses and busi- ness offices of London to the royal city of Westminster. Passage on land was a far different matter and at first only the clergy dared risk living beyond the gates, and then only in strongly-walled dwellings. St. -

LONDON the DORCHESTER Two Day Itinerary: Old Favourites When It Comes to History, Culture and Architecture, Few Cities Can Compete with London

LONDON THE DORCHESTER Two day itinerary: Old Favourites When it comes to history, culture and architecture, few cities can compete with London. To look out across the Thames is to witness first-hand how effortlessly the city accommodates the modern while holding onto its past. Indeed, with an abundance of history to enjoy within its palaces and museums and stunning architecture to see across the city as a whole, exploring London with this one-day itinerary is an irresistible prospect for visitors and residents alike. Day One Start your day in London with a visit to Buckingham Palace, just 20 minutes’ walk from the hotel or 10 minutes by taxi. BUCKINGHAM PALACE T: 0303 123 7300 | London, SW1A 1AA Buckingham Palace is the 775-room official residence of the Royal Family. During the summer, visitors can take a tour of the State Rooms, the Royal Mews and the Queen’s Gallery, which displays the Royal Collection’s priceless artworks. Changing the Guard takes place every day at 11am in summer (every other day in winter) for those keen to witness some traditional British pageantry. Next, walk to Westminster Abbey, just 15 minutes away from the Palace. WESTMINSTER ABBEY T: 020 7222 5152 | 20 Dean’s Yard, London, SW1P 3PA With over 1,000 years of history, Westminster Abbey is another London icon. Inside its ancient stone walls, 17 monarchs have been laid to rest over the course of the centuries. Beyond its architectural and historical significance, the Abbey continues to be the site in which new monarchs are crowned, making it an integral part of London’s colourful biography. -

Edmund Plowden, Master Treasurer of the Middle Temple

The Catholic Lawyer Volume 3 Number 1 Volume 3, January 1957, Number 1 Article 7 Edmund Plowden, Master Treasurer of the Middle Temple Richard O'Sullivan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/tcl Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Catholic Lawyer by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDMUND PLOWDEN' MASTER TREASURER OF THE MIDDLE TEMPLE (1561-1570) RICHARD O'SULLIVAN D ENUO SURREXIT DOMUS: the Latin inscription high on the outside wall of this stately building announces and records the fact that in the year 1949, under the hand of our Royal Treasurer, Elizabeth the Queen, the Hall of the Middle Temple rose again and became once more the centre of our professional life and aspiration. To those who early in the war had seen the destruction of these walls and the shattering of the screen and the disappearance of the Minstrels' Gallery; and to those who saw the timbers of the roof ablaze upon a certain -midnight in March 1944, the restoration of Domus must seem something of a miracle. All these things naturally link our thought with the work and the memory of Edmund Plowden who, in the reign of an earlier Queen Elizabeth, devoted his years as Treasurer and as Master of the House to the building of this noble Hall. -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Temple Church, Inner Temple Lane, London

case study 10 Temple Church, Inner Temple Lane, London Norman in origin Church of Inner and Middle Temple, Inns of Court Architect of refurbishment: Christopher Wren (1632–1723) See St Peter Cornhill (CS9) for information on Sir Christopher Wren Historical note The Temple consists of two societies established for the study and practice of law: the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple. Although both communities function separately and have their own buildings on the site, they both use the same church, known as Temple Church, a reference to its Templar origin. The church was “repaired, adorned and beautified at the joynt expense of the two honourable societies” as praised by John Standish in his sermon after the reopening in 1683. The round church is exemplar for the Templars and is Norman in architec- ture, while the choir is early English. The church underwent subsequent re- pairs and escaped destruction in several fires in 1666, 1677, 1678.1 In 1682 the church was beautified according to “The New View of London” following the reconstruction of many city churches after the Great Fire. A negative descrip- tion of the seventeenth-century alterations is given by Thornbury in 1878. In the reign of Charles II the body of the church was filled with formal pews, which concealed the bases of the columns, while the walls were encumbered, to the height of eight feet from the ground, with oak wain- scoting, which was carried entirely around the church, so as to hide the elegant marble piscine, the interesting almeries over the high altar and the sacrarium on the eastern side of the edifice. -

The Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London HEN Samuel Pepys, a near neighbour of the Penn family at Tower Hill, was awakened by his servant Wabout 3 o'clock on the morning of Sunday, 2nd September, 1666, to be told of a great fire that could be seen in the City, he decided, after looking out of the window, that it was too far away and so returned to bed. Later that morning he realised that this was no ordinary fire, and all that day, and the following days, he was torn between his curiosity to see more of the fire and his anxiety as to the possible damage to his goods, his home and to the Navy Office of which he was Secretary. On the Monday he and Sir William Penn sent some of their possessions down river to Deptford. The narrow congested streets, with bottlenecks at the gates and posterns, where everyone was endeavouring to escape with what goods he could save, added to the con fusion. On the evening of the second day of the fire Pepys and Sir William Penn dug pits in their gardens in which to place their wine; Pepys, remembering his favourite Parmesan cheese, put that in, as well as some of his office papers. Sir William Penn brought workmen from the Dockyard to blow up houses in order to prevent the fire reaching the church of All Hallows by the Tower. The anxiety of Pepys and Penn, their uncertainties whether or not to remove their goods, their lack of sleep and the difficulty of obtaining food, which Pepys records in his Diary, are typical of the problems of the citizens, among whom were a large number of Quakers. -

Minutes Template

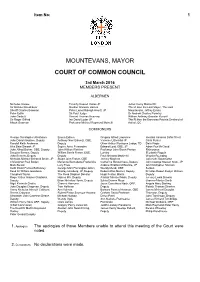

Item No: 1 MOUNTEVANS, MAYOR COURT OF COMMON COUNCIL 3rd March 2016 MEMBERS PRESENT ALDERMEN Nicholas Anstee Timothy Russell Hailes JP Julian Henry Malins QC Sir Michael David Bear Gordon Warwick Haines The Rt Hon the Lord Mayor, The Lord Sheriff Charles Bowman Peter Lionel Raleigh Hewitt, JP Mountevans, Jeffrey Evans Peter Estlin Sir Paul Judge Dr Andrew Charles Parmley John Garbutt Vincent Thomas Keaveny William Anthony Bowater Russell Sir Roger Gifford Ian David Luder JP The Rt Hon the Baroness Patricia Scotland of Alison Gowman Professor Michael Raymond Mainelli Asthal, QC COMMONERS George Christopher Abrahams Emma Edhem Gregory Alfred Lawrence Henrika Johanna Sofia Priest John David Absalom, Deputy Anthony Noel Eskenzi, CBE, Vivienne Littlechild JP Chris Punter Randall Keith Anderson Deputy Oliver Arthur Wynlayne Lodge, TD Delis Regis Alex Bain-Stewart JP Sophie Anne Fernandes Edward Lord, OBE, JP Adam Fox McCloud John Alfred Barker, OBE, Deputy John William Fletcher Professor John Stuart Penton Richardson Douglas Barrow, Deputy William Barrie Fraser, OBE, Lumley Elizabeth Rogula John Bennett, Deputy Deputy Paul Nicholas Martinelli Virginia Rounding Nicholas Michael Bensted-Smith, JP Stuart John Fraser, CBE Jeremy Mayhew James de Sausmarez Christopher Paul Boden Marianne Bernadette Fredericks Catherine McGuinness, Deputy John George Stewart Scott, JP Mark Boleat Lucy Frew Andrew Stratton McMurtrie, JP Ian Christopher Norman Keith David Forbes Bottomley George Marr Flemington Gillon Wendy Mead, OBE Seaton Revd Dr William Goodacre -

The Great Fire of London Year 2

The Great Fire of London Year 2 Key people, places and words Thomas Faryner : owner of the bakery where the fire started. Samuel Pepys : a famous man who wrote a diary about the fire. King Charles II : the King of England in 1666. Christopher Wren : the man who designed new What key facts and dates will we be learning? buildings and a monument to the fire. The Fire of London started on 2nd September 1666 Pudding Lane : the street on which the bakery and lasted for 5 days. was, where the fire started. St Paul’s Cathedral : a famous church which burnt The weather in London was hot and it hadn’t down during the fire. It was rebuilt and still exists rained for 10 months. Houses in London were today. mainly built from wood and straw which is flam- Tower of London : where the king lived in 1666. It mable, especially when it is dry. The houses were did not catch fire because the fire was stopped just also very close together, so the fire could easily before it reached the palace. spread. Bakery : a shop where bread and cakes are made. Timeline Oven : where food is cooked. Today we use gas or 2nd September 1666 - 1:30 am: A fire starts in electricity to heat ovens but in 1666 they burnt Thomas Faryner’s bakery on Pudding Lane in the wood to heat the oven. middle of the night. The fire probably came from Flammable : when something burns easily. the oven. Eyewitness : a person who saw an event with their 2nd September 1666 - 7 am: Samuel Pepys wakes own eyes and can therefore describe it. -

Year 2 Home Learning – 11.05.2020

Year 2 Learning for the week beginning Monday 11th May The maths page numbers in this document relate to the ‘Key Stage One Maths Workout' book, this is the old maths book which was sent out in the original home learning packs. Next week we will move onto the new maths book called ‘Key Stage One Maths Workout'. Monday Maths- Learning objective: To understand the value of tens and ones page 1 and 2 (CGP Extension: Choose your own two or three digit numbers to represent in Workout pictures or using objects. You could represent numbers using drawn tens book) and ones blocks, create your own symbols or use objects like lego! Arithmetic warm up sheet Guided Learning objective: write a list of what you could smell, touch, hear, see reading and taste if you were in this picture Extension: find exciting synonyms (words that mean the same or nearly the same e.g. shining and glimmering) https://www.thesaurus.com English Learning objective: Design your own Cathedral and describe it The Original St Pauls Cathedral was burnt down during The Great Fire of London and the architect Christopher Wren designed a new one. It took almost 40 years to build. Extension: research famous Cathedrals around the world and create a PowerPoint presentation about them Humanities Geography – Points of the compass The points of the compass help us to know which direction things are. A compass will always point to magnetic North at the North Pole. Younger children: Draw and label the four main points of the compass, north, east, south and west. -

Prisoners in .LUDGATE, in the City of London. First Notice. Second Notice. Prisoners in the Compter in GILTSPUR

[ 742 ] Anthony Haiti-sy. ->late of the Parilh of Halifax, in the Thomas Stockton Hatfield, of Red-Cioss Square, Ciippt-i- Townlbip of Warlsj**, in the Comity of York, Taylor. g?.te, in the Parisli aforesaid, late of Aylefoury-Street, hi James Horsefall, late of the Parilh of Halifax, in the Town the Parish of St. James, Clerkenwei'L, Tobacconist. ship of Longfield, in the County of York, Fustian-Maker, Henry Chapman, of thc Rainbow, Cannon-Street, Saint Jonas Nicholason, late of Halifax, in the Pariih of Halifax.. Georges in the East, and late of the George, George-Yard, in the County of York, Book-Binder, Bookseller, and in the Parilh of Saint Sepulchre, Ward of Farringdoa Stationer. Without, Victualler. Joseph Nciiulason/late of Halifax, in the Parish of Halifax, in the County of York, Book-Binder, Bookseller, aud Prisoners in the Compter in GILTSPUR- Stationer. Rohert Powell, late of Halifax, in the Parisli of Halifax, in STREET, in thc City of London. the County of York, Balkct-Makor and Ghs, Dealer. William Sadler, late of the Parisli of Dewsbury, in the Town First Notice. ship oF Dewsbury, in the County of Yoik, Cooper. Henry Hey worth, late of Leeds, in the County of York, John'Waddington, late of the Parilh o'i Halifax, in tlie Merchant. Townlhip os Midgley, in the County of York, Stuff- Jane Kill, late of No. I, Cunier's-Row, and formerly of Maker. No. 3, Ave-Maria-Lanc. Joseph Wilson, late of the Parish of Dewsbury, in the.Town- Ann Ramsay, late of No. -

Y8 History Week Beginning: 11/5/20 the Great Fire of London Please Spend ONE HOUR on Each Lesson This Week

Y8 History Week beginning: 11/5/20 The Great Fire of London Please spend ONE HOUR on each lesson this week. Lesson One: 1) Read through the information below provided about the Great Fire of London and answer the following questions in full sentences: a) What were most buildings in London made of in the 1660s? b) Why were there lots of sheds full of straw, hay and other easily flammable materials? c) What had the weather conditions been like in London during the summer of 1660? d) Where did the fire start? e) Why would the fire reaching the warehouses have made the fire worse? f) What did Samuel Pepys suggest be done to stop the fire from spreading further? g) What did Pepys bury in his garden? Why do you think he did that? h) What was Pepys wearing when he ran away to his friend’s house in Bethnall Green? i) What did the Navy use to create a fire break (a gap between the houses that the fire couldn’t jump across)? j) What damage did the fire cause to London? k) How did people respond to prevent another fire from starting again? 2) There were several reasons why the Fire spread so quickly. Read back through the text provided. For each of the categories below, make a list of as many different reasons for the fire’s spread as you can. Some things may go into several categories: a. The types of building b. The layout of London c. The weather 3) The fire ended up destroying about a quarter of all the buildings in London. -

Newsletter Issue 7 Alternate Layout

ISSUE 7 JANUARY 2007 Inner Temple Library Newsletter Welcome to the Inner Temple Library’s quarterly electronic newsletter. The newsletter AccessToLaw: The Statute aims to keep members and tenants of the Inner Temple up to date with news and Law Database developments in the Library. The Library’s AccessToLaw web site continues to be updated, with new sites being added, and all Saturday Opening current entries being checked and revised every two months. Approval has now been given to make Saturday opening permanent, subject to attendance figures The most notable site added recently is the UK continuing at a satisfactory level. Statute Law Database. This initiative of the DCA’s Statutory Publications Office was released to the One of the four Inn Libraries will be open from public on the 20th December 2006, having been 10.00 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. on each Saturday during under development since the 1990s. the legal terms. The SLD is a database of consolidated UK primary legislation currently in force or in force as at any date from February 1991. UK secondary legislation is available as enacted from 1991. It provides a 2007 historical view of primary legislation for any date February from the first of February 1991 and also allows 3 February Lincoln’s Inn users to view prospective legislation. For each Act 10 February Middle Temple details are given of any amendments since original 17 February Gray’s Inn enactment: amendment date, commencement and 24 February Inner Temple repeal dates, amending instrument citations. It is also possible to view provisions for different jurisdictions (for example, if there are different March versions for England and Wales and for Scotland).