Background Conditions in Upper East Region, Northern Ghana, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper East Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT UPPER EAST REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: ZMK Batse Festus Manu John K. Anarfi Edited by: Samuel K. Gaisie Chief Editor: Tom K.B. Kumekpor ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

South Dayi District

SOUTH DAYI DISTRICT i Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the South Dayi District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Akatsi North District

AKATSI NORTH DISTRICT Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Akatsi North District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Rachel Bauermeister Norwell High School Ossian, IN, USA Ghana, Water Scarcity “Sack Solution” That Saves Ghana Humans Do

Rachel Bauermeister Norwell High School Ossian, IN, USA Ghana, Water Scarcity “Sack Solution” that Saves Ghana Humans do not have the ability to survive without water for prolonged periods of time. Humans need water for almost every bodily process, which is why they can only survive a short time without it. Similarly, countries need water to fulfill their daily needs, such as for irrigation in agriculture. Access to water is the lifeblood of every country. Without access to water in Northern Ghana, the daily tasks they need carry out to survive are limited during the dry seasons. Ghana spans across 238,533 square kilometers of Western Africa. To put this size into a better perspective, Ghana is about the size of Texas. In this vast area lives 28,102,471 people, of which 56.7% live in urban areas, and 43.3% in rural areas. The geography of Ghana is mostly made up of low plains with plateaus in the south-central area. Ghana is most known for being home to the world’s largest artificial lake (“Ghana”). The problems encountered by any nation often cannot be resolved without assistance from the government. The government plays a key role in any project, but also has its own limitations. Both parties’ election platforms have focused on private-sector-driven growth, which will hopefully lead to finding a solution for this water scarcity issue (“Ghana: Current Issues and U.S. Relations in Brief”). Since the food supply is an important matter to ordinary citizens, they can also play a role in supporting their government. -

Assessing Donkey Production and Management in Bunkpurugu/Yunyoo District in the Northern Region of Ghana

Journal of Animal Husbandry and Dairy Science Volume 3, Issue 2, 2019, PP 1-5 ISSN 2637-5354 Assessing Donkey Production and Management in Bunkpurugu/Yunyoo District in the Northern Region of Ghana *Tuaruka, L. and Agbolosu, A. A. Department of Animal Science, University for Development Studies, Ghana *Corresponding Author: Tuaruka, L. Department of Animal Science, University for Development Studies, Ghana ABSTRACT A study was carried out to ascertain the production and management of donkeys in some communities in the Bunkpurugu/Yunyoo district. Ten communities were purposively sampled and the donkey owners were sampled using snowball sampling. A total of 100 donkey owners were interviewed using semi-structured questionnaires on biographical information of farmers, flock structure and management systems, feeding and watering, reproduction and breeding and diseases, mortality and management. Linear body measurements such as Heart girth circumference (HG), Height at withers (HW), Body length (BL), Neck length (NL) and Head length (HL) were taken on 144 donkeys. Donkey keeping is an important activity to farmers in the district. They provide cheap means of transport to farmers who cannot afford mechanical power. Their use for supplying water to household was ranked (1.31) as the most important role whereas carting of goods to market and farm implements to and from farms was the second most important role. The least role was for income generation. Donkeys roam and graze freely during the dry season but are tethered during the rainy season to graze. The animals mate randomly at pastures. Sores on the skin, worm infestation and foot diseases were some of the diseases conditions identified. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Next-Generation IRS Project

Next-generation IRS project Stakeholders Meeting Liverpool Next-generation IRS project Stakeholder Forum September 19, 2019, Liverpool 2 Building Partnerships Creating Solutions Saving Lives NgenIRS in Mali 3 Building Partnerships Creating Solutions Saving Lives IRS implementation - Mali District 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Koulikoro Fana Barouéli Ségou Bla Mopti Bandiagara Bankass Djenné control (no spray) pyrethroid bendiocarb pirimiphos-methyl Source: World Malaria Report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. The dominant vector populations, Anopheles gambiae, are highly resistant to pyrethroids 4 Building Partnerships Creating Solutions Saving Lives NgenIRS copay-supported volumes - Mali Estimated increase in the number of Mali first participated in 2016. Since then, NgenIRS investments have people protected because of NgenIRS increased the number of people protected by third-generation IRS (3GIRS) investments (Since 2016 – Across products substantially Africa) 90.0 823,000 people 80.0 77.5m protected in 70.0 48.6% 2017 increase 665,000 60.0 people 52.1m 50.0 protected in 2018 40.0 789,000 People covered people 30.0 protected in 2016 570–1,150 20.0 deaths 10.0 prevented 0.0 Likely leading to… 190,000– - 385,000 clinical cases With payco & prevented At full price discountedprice 5 Building Partnerships Creating Solutions Saving Lives IRS impact - Mali Observational analysis of impact of IRS (including 3GIRS) from 2011-2014 in Ségou: 31% reduction in malaria cases reporting to -

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana

Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana Small and medium forest enterprises (SMFEs) serve as the main or additional source of income for more than three million Ghanaians and can be broadly categorised into wood forest products, non-wood forest products and forest services. Many of these SMFEs are informal, untaxed and largely invisible within state forest planning and management. Pressure on the forest resource within Ghana is growing, due to both domestic and international demand for forest products and services. The need to improve the sustainability and livelihood contribution of SMFEs has become a policy priority, both in the search for a legal timber export trade within the Voluntary Small and Medium Partnership Agreement (VPA) linked to the European Union Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade (EU FLEGT) Action Plan, and in the quest to develop a national Forest Enterprises strategy for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This sourcebook aims to shed new light on the multiple SMFE sub-sectors that in Ghana operate within Ghana and the challenges they face. Chapter one presents some characteristics of SMFEs in Ghana. Chapter two presents information on what goes into establishing a small business and the obligations for small businesses and Ghana Government’s initiatives on small enterprises. Chapter three presents profiles of the key SMFE subsectors in Ghana including: akpeteshie (local gin), bamboo and rattan household goods, black pepper, bushmeat, chainsaw lumber, charcoal, chewsticks, cola, community-based ecotourism, essential oils, ginger, honey, medicinal products, mortar and pestles, mushrooms, shea butter, snails, tertiary wood processing and wood carving. -

Rain Rate and Rain Attenuation Geographical Map for Satellite System Planning in Ghana

International Journal of Computer Applications (0975 – 8887) Volume 177 – No. 41, March 2020 Rain Rate and Rain Attenuation Geographical Map for Satellite System Planning in Ghana Stephen Akobre Mohammed Ibrahim Daabo Abdul-Mumin Salifu Dept. of Computer Science Dept. of Computer Science Dept. of Computer Science University for Development Studies University for Development Studies University for Development Studies Navrongo, Ghana Navrongo, Ghana Navrongo, Ghana ABSTRACT the rain rate and attenuation. These studies have been carried Good signal reception depends on a reliable communication out mostly in the temperate regions. But the severity of rain link. However, as the signal travels through the effect on the signal, are more pronounce at the tropics and communication medium, several factors affect the quality of equatorial regions where intense rainfall events are common the signal at the receiver. In Ku band digital satellite as compared to the temperate regions. This is reported in the transmission, rain is the major cause of link impairment. work of Ajayi (1996), Moupfouma (1985) and Ojo and Global rain rate and rain attenuation prediction models have Omotosho (2013). been developed to predict rain rate and rain attenuation at Satellite system design requires as input 1-minute rain rate various locations. These models have not been applied and data with various exceedance probabilities. Based on this tested with measured data to determine their prediction many researchers have conducted experiments on their local accuracy in the Ghanaian tropical region. In this paper, the climatological regions to measure 1-minute rain rate and Moupfouma and International Telecommunication Union attenuation. In regions where there are enough data coverage, Recommendation (ITU-R) rain rate models were applied and prediction models have been proposed. -

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic

Document of the International Fund for Agricultural Development Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II Interim Evaluation May 2006 Report No. 1757-GH Photo on cover page: Republic of Ghana Members of a Functional Literacy Group at Katia (Upper East Region) IFAD Photo by: R. Blench, OE Consultant Republic of Ghana Upper East Region Land Conservation and Smallholder Rehabilitation Project (LACOSREP) – Phase II, Loan No. 503-GH Interim Evaluation Table of Contents Currency and Exchange Rates iii Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Map v Agreement at Completion Point vii Executive Summary xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Background of Evaluation 1 B. Approach and Methodology 4 II. MAIN DESIGN FEATURES 4 A. Project Rationale and Strategy 4 B. Project Area and Target Group 5 C. Goals, Objectives and Components 6 D. Major Changes in Policy, Environmental and Institutional Context during 7 Implementation III. SUMMARY OF IMPLEMENTATION RESULTS 9 A. Promotion of Income-Generating Activities 9 B. Dams, Irrigation, Water and Roads 10 C. Agricultural Extension 10 D. Environment 12 IV. PERFORMANCE OF THE PROJECT 12 A. Relevance of Objectives 12 B. Effectiveness 12 C. Efficiency 14 V. RURAL POVERTY IMPACT 16 A. Impact on Physical and Financial Assets 16 B. Impact on Human Assets 18 C. Social Capital and Empowerment 19 D. Impact on Food Security 20 E. Environmental Impact 21 F. Impact on Institutions and Policies 22 G. Impacts on Gender 22 H. Sustainability 23 I. Innovation, Scaling up and Replicability 24 J. Overall Impact Assessment 25 VI. PERFORMANCE OF PARTNERS 25 A. -

A COMMUNITY PARK for the TOWN of AKYEM ODA, GHANA By

THE THREE AKYEM: A COMMUNITY PARK FOR THE TOWN OF AKYEM ODA, GHANA by ALEXANDER NAGEL (Under the Direction of Pratt Cassity) ABSTRACT This thesis presents a program and design for a new community park for Akyem Oda, a small town in the rain forest region of Ghana. The town was visited two times in 2004 and 2005 as part of the ongoing yearly Summer Service-Learning Studio during which time a site inventory was performed. Background research for the program development included geography and history of Ghana with a special focus on the Asante kingdom, traditional building techniques, land planning and an exploration of Akyem history in relationship to the dominant kingdom of Asante. A photo documentation of the main features of Akyem Oda and their spatial relationships to each other completes the research part of this thesis. The program for the proposed ‘Three Akyem Community Park’ integrates a Parade Ground, a Cultural Center and three Groves representing each of the three Akyem people on the 8.9 acres rectilinear site. INDEX WORDS: Africa, Akyem Oda, Architecture, Asante, Cultural Center, Community Park, Courtyard House, Diaspora, Ghana, Grove, Land Planning, Parade Ground, Service-Learning, Tourism THE THREE AKYEM: A COMMUNITY PARK FOR THE TOWN OF AKYEM ODA, GHANA by ALEXANDER NAGEL Diploma, Tuebingen University, Germany, 1996 M.S., The University of Georgia, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Alexander Nagel All Rights Reserved THE THREE AKYEM: A COMMUNITY PARK FOR THE TOWN OF AKYEM ODA, GHANA by ALEXANDER NAGEL Major Professor: Pratt Cassity Committee: Mary Anne Akers Karim Traore Jennifer Perissi Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who in different ways helped me along the way towards completion of my program and this thesis. -

General Information

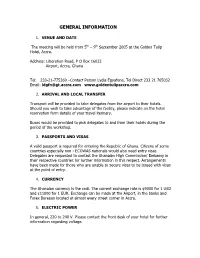

GENERAL INFORMATION 1. VENUE AND DATE The meeting will be held from 5th – 9th September 2005 at the Golden Tulip Hotel, Accra. Address: Liberation Road, P O Box 16033 Airport, Accra, Ghana Tel: 233-21-775360 –Contact Person Lydia Egyafene, Tel Direct 233 21 765032 Email: [email protected] www.goldentulipaccra.com 2. ARRIVAL AND LOCAL TRANSFER Transport will be provided to take delegates from the airport to their hotels. Should you wish to take advantage of the facility, please indicate on the hotel reservation form details of your travel iterinary. Buses would be provided to pick delegates to and from their hotels during the period of the workshop. 3. PASSPORTS AND VISAS A valid passport is required for entering the Republic of Ghana. Citizens of some countries especially non - ECOWAS nationals would also need entry visas. Delegates are requested to contact the Ghanaian High Commission/ Embassy in their respective countries for further information in this respect. Arrangements have been made for those who are unable to secure visas to be issued with visas at the point of entry. 4. CURRENCY The Ghanaian currency is the cedi. The current exchange rate is ¢9000 for 1 USD and ¢11000 for 1 EUR. Exchange can be made at the Airport, in the banks and Forex Bureaux located at almost every street corner in Accra. 5. ELECTRIC POWER In general, 220 to 240 V. Please contact the front desk of your hotel for further information regarding voltage. 6. LOCATION Ghana is located on West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea only a few degrees north of the equator, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean between Cote d'Ivoire and Togo.