Letters from a Lovelorn Captain Jonathan Varcoe1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POLGOOTH TIMES Winter 2007

May I take this opportunity of thanking Pam, both personally and on 98 POLGOOTH TIMES Winter 2007 behalf of the committee, for her hard work, her knowledge of the village, which she readily shared with us, and her commitment to the 2007 already - it village magazine. However, we won’t lose contact with Pam as she has doesn’t seem 7 years agreed to continue compiling and delivering the Polgooth Times. ago we were Thank you Pam. celebrating or Another thank you goes to Hazel Old whose photograph of the deliberating on the village was used on the front cover of our last issue and also to millennium. We Brendan Sweet for this front cover photograph. have probably all Lastly, please don’t forget my earlier plea for frog spawn – I will seen some changes willingly collect. to our own lives The next date for articles to be since then, some The Editor submitted for the 99th edition is 13th April 2007 good and some sad. I certainly have. Pam Gibbs, presented with flowers from The Committee of The Polgooth Times, Politically and in the at a Thank You meal at The Polgooth Inn. world as a whole there have been many changes and upheavals which give us all reasons to reflect as the new year begins, so lets hope 2007 will be a healthy and happy year and that wars and disagreements will be a thing of the past. An impossibility, I am sure you agree. However, perhaps we could all make an effort to live peacefully with our neighbours in this lovely part of Cornwall and make our own small contribution to a peaceful world. -

January-2021

CALENDAR DATES for JANUARY What’s On in Thurs 31st Dec. Mobile Library – see details Chacewater below 28th January Contact Details st Fri. 1 Bank Holiday Editorial: Tel: 01872 399560 Sat. 2nd Christmas Decorations to be Email:-editor@ taken down. Meet Kings Head car whatsoninchacewater.co.uk park, all welcome, more hands less time taken. 9.30 am What’s On is published and delivered Sun. 3rd CRoW Walk starting in the village across the car park, all welcome. 9.30 am parish every month. Copy Fri. 8th Chacewater Parish Council deadline is at Meeting. To be held on Zoom noon on the please contact the Parish Clerk if 18th day of you wish to attend. 7.00 pm the month [email protected] before. Contact the Editorial Team Mon. 11th Leat, Shute and Green for advice or help. Clear ance Clean-up. Clear silt & vegetation, Meet at Advertising: Sergeants Hill/Leat Bridge. Print-Out 9:30 am. Tel: 01872 242534 Email:- Tue. 12th Leat, Shute & Green Clean-up. [email protected] Day Two. 9:30 am. The inclusion of any article or Wed. 13th New Moon - 5:00 am. advertisement in this magazine does not constitute Thur. 28th MOBILE LIBRARY any form of accreditation by at Twelveheads the editors. The editors are 11:50 am. – 12:10 pm. unable to vouch for the MOBILE LIBRARY at Chacewater professional qualifications, Car Park 13:20 pm. – 14:00 pm. etc. of any advertiser. Readers must satisfy Full Moon - 19:16 pm. themselves that an advertiser meets their requirements. Fri. 29th Chacewater Parish Council Meeting. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS CORNWALL COUNCIL VOTING AREA Referendum on the United Kingdom's membership of the European Union 1. A referendum is to be held on THURSDAY, 23 JUNE 2016 to decide on the question below : Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union? 2. The hours of poll will be from 7am to 10pm. 3. The situation of polling stations and the descriptions of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows : No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 301 STATION 2 (AAA1) 1 - 958 CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 301/1 STATION 1 (AAM4) 1 - 212 THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS KINGFISHER DRIVE PL25 3BG 302 CUDDRA W I HALL (AAA2) 1 - 430 BUCKLERS LANE HOLMBUSH ST AUSTELL PL25 3HQ 303 BETHEL METHODIST CHURCH (AAB1) 1 - 1,008 BROCKSTONE ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DW 304 BISHOP BRONESCOMBE SCHOOL (AAB2) 1 - 879 BOSCOPPA ROAD ST AUSTELL PL25 3DT KATE KENNALLY Dated: WEDNESDAY, 01 JUNE, 2016 COUNTING OFFICER Printed and Published by the COUNTING OFFICER ELECTORAL SERVICES, ST AUSTELL ONE STOP SHOP, 39 PENWINNICK ROAD, ST AUSTELL, PL25 5DR No. of Polling Station Situation of Polling Station(s) Description of Persons entitled to vote 305 SANDY HILL ACADEMY (AAB3) 1 - 1,639 SANDY HILL ST AUSTELL PL25 3AW 306 STATION 2 (AAG1) 1 - 1,035 THE COMMITTEE ROOM COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK ROAD PL25 5DR 306/1 STATION 1 (APL3) 1 - 73 THE COMMITTEE ROOM CORNWALL COUNCIL OFFICES PENWINNICK -

Just a Balloon Report Jan 2017

Just a Balloon BALLOON DEBRIS ON CORNISH BEACHES Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition | January 2017 BACKGROUND This report has been compiled by the Cornish Plastic Pollution Coalition (CPPC), a sub-group of the Your Shore Network (set up and supported by Cornwall Wildlife Trust). The aim of the evidence presented here is to assist Cornwall Council’s Environment Service with the pursuit of a Public Spaces Protection Order preventing Balloon and Chinese Lantern releases in the Duchy. METHODOLOGY During the time period July to December 2016, evidence relating to balloon debris found on Cornish beaches was collected by the CPPC. This evidence came directly to the CPPC from members (voluntary groups and individuals) who took part in beach-cleans or litter-picks, and was accepted in a variety of formats:- − Physical balloon debris (latex, mylar, cords & strings, plastic ends/sticks) − Photographs − Numerical data − E mails − Phone calls/text messages − Social media posts & direct messages Each piece of separate balloon debris was logged, but no ‘double-counting’ took place i.e. if a balloon was found still attached to its cord, or plastic end, it was recorded as a single piece of debris. PAGE 1 RESULTS During the six month reporting period balloon debris was found and recorded during beach cleans at 39 locations across Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly shown here:- Cornwall has an extensive network of volunteer beach cleaners and beach cleaning groups. Many of these are active on a weekly or even daily basis, and so some of the locations were cleaned on more than one occasion during the period, whilst others only once. -

St Mewan Neighbourhood Development Plan

ST MEWAN PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2016-2030 Written on behalf of the community of St Mewan Parish st Version 17 – Examiner’s Final - 31 January 2018 1 The St Mewan Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan Area comprises of the Parish of St. Mewan as identified within the 2013 designation map. DOCUMENT INFORMATION TITLE St Mewan Neighbourhood Development Plan Produced by: St Mewan Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan Steering Group With support from: Cornwall Rural Community Charity (CRCC) 2 CONTENTS PAGE Page Foreword 4 Non-Technical Summary 5 Neighbourhood Development Plan Process 6 Policy Overview 7 Policy 1: Housing Development within Settlement Boundaries 8 - 10 Policy 2: Rural Exception Sites 11 - 13 Policy 3: Natural Environment 14 Policy 4: Environment - Open Areas of Significance Trewoon 15 - 16 Policy 5: Environment – Open Areas of Significance Polgooth 17 - 18 Policy 6: Heritage 19 - 20 Policy 7: Economic 21 - 23 Policy 8: Infrastructure 24 - 25 Policy 9: Community Facilities 26 - 27 Policy 10: Open Spaces 28 - 29 Policy 11: Landscape Character Areas 30 - 31 Appendix 1: Settlement Map Trewoon Appendix 2: Settlement Map Sticker Appendix 3: Settlement Map Polgooth with Trelowth Appendix 4: Settlement Map Hewas Water Appendix 5: St Mewan Parish Map The following documents are Supplementary to this Neighbourhood Development Plan and are displayed on the website www.wearestmewan.org.uk 1: Consultation Statement 2: Basic Conditions Statement 3: Evidence Report 3 FOREWORD The St Mewan Parish Neighbourhood Development Plan is a blueprint for how we, the local community, view the future of our Parish. It describes how we want the St Mewan Parish to look and what it will be like to live here, work here and visit here over the Plan period for the next 14 years. -

Woodland at Pentewan, Pentewan, St Austell, Cornwall, PL26 6BJ

Woodland At Pentewan, Pentewan, St Austell, Cornwall, PL26 6BJ A delightful deciduous bluebell woodland close to a popular beach Mevagissey 2 miles - Beach 0.3 miles - St Austell 4 miles - Truro 16 miles • A delightful bluebell woodland • Secluded and peaceful position • Stream-side location • Close to Pentewan Beach • Copious supply of firewood • Abundance of wildlife & wild flowers, • 11.4 acres • Guide price £45,000 01872 264488 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk Woodland At Pentewan, Pentewan, St Austell, Cornwall, PL26 6BJ SITUATION The whole area is a haven for wildlife, bluebells, wild The woodland is situated in a peaceful position, garlic woodland anemone and other wild flowers and approximately 550m from Pentewan beach, on the will appeal to buyers with an interest in nature. banks of a stream. The historic fishing village of Mevagissey is about 2 miles to the south and The Lost Families who may be looking for an area for children to Gardens of Heligan are just 3 miles away. The town of explore (taking care near the old quarry), play or St Austell has a comprehensive range of every day perhaps enjoy the stream, are also likely to find the facilities and amenities and lies approximately 4 miles woodland appealing. It would also be well suited to to the north. The cathedral city of Truro, being the people wanting to own their own attractive, woodland commercial and retail centre of Cornwall, is nestled in picturesque Cornish countryside, close to a approximately 16 miles to the west. From St Austell popular beach. -

Cornwall Industrial Settlements Initiative POLGOOTH

Report No: 2004R094 Cornwall Industrial Settlements Initiative POLGOOTH (St Austell Area) 2004 CORNWALL INDUSTRIAL SETTLEMENTS INITIATIVE Conservation Area Partnership Name: Polgooth Study Area: St Austell Valley Council: Restormel Borough Council NGR: SW 99548 50464 (centre) Location: South-east Cornwall, 1 mile Existing No south-west of St Austell CA? Main period of Pre 1809; Main Tin, copper mining and elvan quarry industrial settlement 1809-41 industry: growth: Industrial history and significance Polgooth developed relatively early. Little survives from the early years of the mine in the 16th- 18th centuries when Polgooth was associated with some of the major county families and prominent engineers. This said, there is a good level of survival from the early nineteenth century in the form of workers cottages, the Inn, Count House and the intricate street patterns and leats developed in association with the mine. One of the most enduring legacies of the settlement’s industrial past, however, comes not from the mine but the quarry to the south of the settlement which provided the material for the majority of Polgooth’s buildings. Polgooth is a classic type of early industrial settlement, an uncoordinated scatter of smallholdings on the edge of common land divided between the two parishes of St Mewan and St Ewe (in fact three if the mine area outside the settlement within St Austell is included). Cottages were fitted in and amongst still-working or recently finished mines and processing sites, all set on the no-man’s land of waste, some distance from their respective churchtowns, in land shared by two or three large landowners, often in dispute over overall control of the area. -

Responsibilities for Flood Risk Management

Appendix A - Responsibilities for Flood Risk Management The Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has overall responsibility for flood risk management in England. Their aim is to reduce flood risk by: • discouraging inappropriate development in areas at risk of flooding. • encouraging adequate and cost effective flood warning systems. • encouraging adequate technically, environmentally and economically sound and sustainable flood defence measures. The Government’s Foresight Programme has recently produced a report called Future Flooding, which warns that the risk of flooding will increase between 2 and 20 times over the next 75 years. The report produced by the Office of Science and Technology has a long-term vision for the future (2030 – 2100), helping to make sure that effective strategies are developed now. Sir David King, the Chief Scientific Advisor to the Government concluded: “continuing with existing policies is not an option – in virtually every scenario considered (for climate change), the risks grow to unacceptable levels. Secondly, the risk needs to be tackled across a broad front. However, this is unlikely to be sufficient in itself. Hard choices need to be taken – we must either invest in more sustainable approaches to flood and coastal management or learn to live with increasing flooding”. In response to this, Defra is leading the development of a new strategy for flood and coastal erosion for the next 20 years. This programme, called “Making Space for Water” will help define and set the agenda for the Government’s future strategic approach to flood risk. Within this strategy there will be an overall approach to the assessing options through a strong and continuing commitment to CFMPs and SMPs within a broader planning framework which will include River Basin Management Plans prepared under the Water Framework Directive and Integrated Coastal Zone Management. -

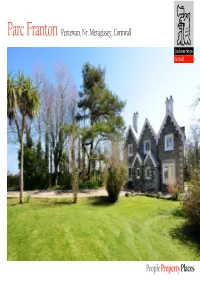

Parc Franton Pentewan, Nr. Mevagissey, Cornwall

Parc Franton Pentewan, Nr. Mevagissey, Cornwall An individual country home recently refurbished, close to the quaint harbourside village of Mevagissey Guide Price £575,000 Features The Property • Generous Kitchen/Breakfast Room Originally part of the Heligan Estate and still • Sitting Room retaining many original architectural features, Parc Franton has been comprehensively • Dining Room refurbished incorporating oak and ceramic • Snug floors, pleasing and well-appointed • Cloakroom kitchen/breakfast room in a range of cream units • Utility Room and a four oven Aga. The property is secluded down a long driveway which provides total • 5 Bedrooms privacy. An adjacent paddock of about 1 acre • En-Suite Shower Room has been leased for some 30 years or so by the • Walk in Wardrobe owners of Parc Franton from the Tremayne • Family Bathroom Estate and it is envisaged that this arrangement could be continued. • Double Carport • Games Room • Stables The Location • Mature Gardens The house is surrounded by its gardens and • 1 Acre Paddock (on Lease) grounds in a secluded setting down a driveway • Secluded Setting of 100 yards or so overlooking rolling countryside and close to the popular harbourside village of Mevagissey. The Lost Distances Gardens of Heligan are close by and can be seen • Mevagissey 1.3 miles across the fields from the rear gardens. Much of • St Austell 4.8 miles the surrounding countryside still remains in the • Truro 19 miles ownership of the Tremayne Estate. • Heligan Gardens 1.3 miles The Cathedral City and administrative centre of • Eden Project 9 miles Truro is some 19 miles to the west with the main commercial town of St Austell some 5 miles to (distances approximately) the north east, both providing multiple shopping facilities and main line rail stations to London Paddington. -

ST MEWAN PARISH COUNCIL Parish Clerk: Wendy Yelland (Cilca) Kerenza the Chase, Sticker St Austell PL26 7HL Tele: 07464 350837

ST MEWAN PARISH COUNCIL Parish Clerk: Wendy Yelland (CiLCA) Kerenza The Chase, Sticker St Austell PL26 7HL Tele: 07464 350837 E: [email protected] W: www.stmewanparishcouncil.gov.uk Follow us on Facebook & Twitter 13th February 2020 TO MEMBERS OF THE PLANNING COMMITTEE I hereby give notice that the Planning Meeting of St Mewan Parish Council will be held on Thursday 20th February 2020 at St Marks Church Hall, Sticker commencing at 09.45am. All Members of the Council are hereby summoned to attend for the purpose of considering and resolving upon the business about to be transacted at the meeting as set out hereunder. Yours faithfully Wendy Yelland Wendy Yelland Parish Clerk/RFO Press & Public are invited to attend. Meetings are held in public and could be filmed or recorded by broadcasters, the media or members of the public. AGENDA 1. Persons Present/Apologies To NOTE persons, present and RECEIVE apologies for absence. 2. Declarations of Interest from Members / Dispensations To RECEIVE any Declarations of Interest from Members. To RESOLVE to grant any requests for Dispensation in line with the Councillor Code of Conduct 2012 if appropriate. 3. Planning Meeting: Minutes 17th January 2020 To RESOLVE that the above Minutes of the Planning Meeting of St Mewan Parish Council having been previously circulated, be taken as read, approved and signed. 4. Matters Arising To NOTE any matters arising from the minutes. While I/Members may express an opinion for or against a proposal at this meeting, my/our mind(s) is/are not closed, and I/we will only come to a conclusion on whether I/we should support the scheme or offer an objection after I/we have listened to the full debate and in receipt of a planning application. -

Notice of Election TP West

Notice of Election Election of Town and Parish Councillors Notice is hereby given that 1. Elections are to be held of Town and Parish Councillors for each of the under-mentioned Town and Parish Councils. If the elections are contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May, 2021. 2. I have appointed Holly Gamble, Claire Jenkin, Ruth Naylor, Sharon Richards, John Simmons, Geoffrey Waxman and Alison Webb whose offices are Room 11, Cornwall Council, St Austell Information Service, 39 Penwinnick Road, St Austell, PL25 5DR and 3S, County Hall, Truro TR1 3AY to be my Deputies and are specifically responsible for the following Towns and Parishes: Towns and Parishes within St Ives Electoral Divisions (SI) Seats Seats Seats Seats Breage 12 Ludgvan (Long Rock Ward) 2 Perranuthnoe (Goldsithney Ward) 7 St Keverne (Coverack Ward) 4 Crowan 13 Madron (Gulval Ward) 6 Perranuthnoe (Perranuthnoe Ward) 3 St Keverne (St Keverne Ward) 9 Cury 7 Madron (Madron Ward) 6 Porthleven 9 St Levan 10 Germoe 7 Manaccan 7 St Buryan, Lamorna and Paul 12 St Martin-in-Meneage 7 Grade Ruan 12 Marazion 11 St Erth 11 Sancreed 10 Gweek 7 Mawgan-in-Meneage 10 St Hilary 10 Sennen 10 Helston (North Ward) 8 Mullion 10 St Ives (Halsetown Ward) 5 Sithney (Lowertown Ward) 1 Helston (South Ward) 6 Penzance (Heamoor & Gulval Ward) 3 St Ives (Lelant Ward) 6 Sithney (Sithney Ward) 8 Landewednack 10 Penzance (Newlyn & Mousehole Ward) 5 St Ives (St Ives East & Carbis Bay Ward) 2 Towednack 7 Ludgvan (Crowlas Ward) 6 Penzance (Penzance East Ward) 6 St Ives (St Ives West Ward) 3 Wendron -

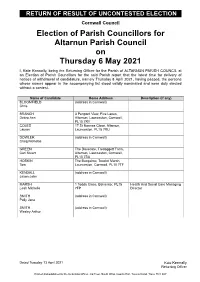

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest.