Let Us Know How Access to This Document Benefits You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(405) 527-0640 (580) 476-3033 (580) 759-3331

Ready-Made Adventures. Take the guesswork out of your getaway. AdventureRoad.com features more than 50 Oklahoma road trips for every interest, every personality and every budget. All the planning’s done — all you have to do is hit the road. AdventureRoad.com #MyAdventureRoad Adventure Road @AdventureRoadOK @AdventureRoad UNI_16-AR-068_CNCTVisitorsGuide2017_Print.indd 1 8/19/16 4:38 PM Ready-Made Adventures. Take the guesswork out of your getaway. AdventureRoad.com features more than 50 Oklahoma road trips for every interest, every personality and every budget. All the planning’s done — all you have to do is hit the road. 3 1 2O 23 31 4₄ Earth 1Air Golf Fire Water Listings Northeast Southwest Courses Northwest Southeast Businesses CHICKASAW COUNTRY CHICKASAW COUNTRY Distances from major regional cities to the GUIDE 2017 GUIDE 2017 Chickasaw Nation Welcome Center in Davis, OK Miles Time Albuquerque, NM 577 8hrs 45min Amarillo, TX 297 4hrs 44min Austin, TX 316 4hrs 52min Branson, MO 394 5hrs 42min Colorado Springs, CO 663 10hrs 7min CHICKASAWCOUNTRY.COM CHICKASAWCOUNTRY.COM Dallas, TX 134 2hrs 15min HAVE YOU SEEN OUR COVERS? We've designed four unique covers - one for each quadrant of Fort Smith, AR 213 3hrs 23min Chickasaw Country - Northeast (Earth), Southwest (Air), Northwest (Fire) and Southeast (Water). Houston, TX 374 5hrs 30min Each cover speaks to the element that's representative of that quadrant. Joplin, MO 287 4hrs 12min Return to your roots in Earth. Let your spirit fly in Air. Turn up the heat in Fire. Make a splash in Water. Kansas City, MO 422 5hrs 57min Each quadrant of Chickasaw Country offers some of the best attractions, festivals, shops, restaurants Little Rock, AR 369 5hrs 31min and lodging in Oklahoma. -

1715 Total Tracks Length: 87:21:49 Total Tracks Size: 10.8 GB

Total tracks number: 1715 Total tracks length: 87:21:49 Total tracks size: 10.8 GB # Artist Title Length 01 Adam Brand Good Friends 03:38 02 Adam Harvey God Made Beer 03:46 03 Al Dexter Guitar Polka 02:42 04 Al Dexter I'm Losing My Mind Over You 02:46 05 Al Dexter & His Troopers Pistol Packin' Mama 02:45 06 Alabama Dixie Land Delight 05:17 07 Alabama Down Home 03:23 08 Alabama Feels So Right 03:34 09 Alabama For The Record - Why Lady Why 04:06 10 Alabama Forever's As Far As I'll Go 03:29 11 Alabama Forty Hour Week 03:18 12 Alabama Happy Birthday Jesus 03:04 13 Alabama High Cotton 02:58 14 Alabama If You're Gonna Play In Texas 03:19 15 Alabama I'm In A Hurry 02:47 16 Alabama Love In the First Degree 03:13 17 Alabama Mountain Music 03:59 18 Alabama My Home's In Alabama 04:17 19 Alabama Old Flame 03:00 20 Alabama Tennessee River 02:58 21 Alabama The Closer You Get 03:30 22 Alan Jackson Between The Devil And Me 03:17 23 Alan Jackson Don't Rock The Jukebox 02:49 24 Alan Jackson Drive - 07 - Designated Drinke 03:48 25 Alan Jackson Drive 04:00 26 Alan Jackson Gone Country 04:11 27 Alan Jackson Here in the Real World 03:35 28 Alan Jackson I'd Love You All Over Again 03:08 29 Alan Jackson I'll Try 03:04 30 Alan Jackson Little Bitty 02:35 31 Alan Jackson She's Got The Rhythm (And I Go 02:22 32 Alan Jackson Tall Tall Trees 02:28 33 Alan Jackson That'd Be Alright 03:36 34 Allan Jackson Whos Cheatin Who 04:52 35 Alvie Self Rain Dance 01:51 36 Amber Lawrence Good Girls 03:17 37 Amos Morris Home 03:40 38 Anne Kirkpatrick Travellin' Still, Always Will 03:28 39 Anne Murray Could I Have This Dance 03:11 40 Anne Murray He Thinks I Still Care 02:49 41 Anne Murray There Goes My Everything 03:22 42 Asleep At The Wheel Choo Choo Ch' Boogie 02:55 43 B.J. -

The 1St Marine Division and Its Regiments

thHHarine division and its regiments HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON, D.C. A Huey helicopter rapidly dispatches combat-ready members of Co C, 1st Bn, 1st Mar, in the tall-grass National Forest area southwest of Quang Tri in Viet- nam in October 1967. The 1st Marine Division and Its Regiments D.TSCTGB MARINE CORPS RESEARCH CENTER ATTN COLLECTION MANAGEMENT (C40RCL) MCCDC 2040 BROADWAY ST QUANTICOVA 22134-5107 HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON, D.C. November 1981 Table of Contents The 1st Marine Division 1 The Leaders of the Division on Guadalcanal 6 1st Division Commanding Generals 7 1st Marine Division Lineage 9 1st Marine Division Honors 11 The 1st Division Patch 12 The 1st Marines 13 Commanding Officers, 1st Marines 15 1st Marines Lineage 18 1st Marines Honors 20 The 5th Marines 21 Commanding Officers, 5th Marines 23 5th Marines Lineage 26 5th Marines Honors 28 The 7th Marines 29 Commanding Officers, 7th Marines 31 7th Marines Lineage 33 7th Marines Honors 35 The 1 1th Marines 37 Commanding Officers, 11th Marines 39 1 1th Marines Lineage 41 1 1th Marines Honors 43 iii The 1st Marine Division The iST Marine Division is the direct descendant of the Marine Corps history and its eventual composition includ- Advance Base Brigade which was activated at Philadelphia ed the 1st, 5th, and 7th Marines, all infantry regiments, on 23 December 1913. During its early years the brigade and the 11th Marines artillery regiment. Following the was deployed to troubled areas in the Caribbean. -

American Square Dance Vol. 37, No. 8

Single AMERICAN Annual Issue $9.00 $1.00 SQUARE DANCE L AUGUST 1982 NOW THE DANCE OF AMERICA: DANCING- "THE BOSS" by Wog Power enough for 100 squares— twice the power of our previous models, yet small and lightweight for quick, convenient portability. Exceptional Reliability— proven in years of square dance use. A $1,000. Value— but priced at just $635.! • gr S Why the P-400 Is the Finest Professional Sound System Available This 17-pound system, housed in a 14"x14"x5" sewn vinyl carrying is easy to transport and set up, yet will deliver an effortless 120 R.M.S. watts of clear, clean power. Conservative design which lets the equipment "loaf"results In high reliability and long life. Yet this small powerhouse has more useful features than we have ever offered before: VU meter for convenient visual sound level indication Two separate power amplifiers Two separately adjustable microphone channels Optional remote music control 5-gram stylus pressure for extended record life (Others use up to 10!) Internal strobe BUILT-IN music-only monitor power amplifier Tape input and output Convenient control panel Exclusive Clinton Features Only Clinton has a floating pickup/turntable suspension, so that an accidental bump as you reach for a control knob will not cause needle skip. Only Clinton equipment can be operated on an inverter, on high line voltage, or under conditions of output overload without damage. Only Clinton offers a dual speed control— normal and extended range (0-80 r.p.m.) and automatic speed change from 33 to 45 rpm. -

1 Column Unindented

DJ PRO OKLAHOMA.COM TITLE ARTIST SONG # Just Give Me A Reason Pink ASK-1307A-08 Work From Home Fifth Harmony ft.Ty Dolla $ign PT Super Hits 28-06 #thatpower Will.i.am & Justin Bieber ASK-1306A-09 (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes MH-1016 (Kissed You) Good Night Gloriana ASK-1207-01 1 Thing Amerie & Eve CB30053-02 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's CB30094-04 1,000 Faces Randy Montana CB60459-07 1+1 Beyonce Fall 2011-2012-01 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray CBE9-23-02 100 Proof Kellie Pickler Fall 2011-2012-01 100 Years Five For Fighting CBE6-29-15 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Media Pro 6000-01 11 Cassadee Pope ASK-1403B 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan CBE7-23-03 Len Barry CBE9-11-09 15 Minutes Rodney Atkins CB5134-03-03 18 And Life Skid Row CBE6-26-05 18 Days Saving Abel CB30088-07 1-800-273-8255 Logic Ft. Alessia Cara PT Super Hits 31-10 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Media Pro 6000-01 19 You + Me Dan & Shay ASK-1402B 1901 Phoenix PHM1002-05 1973 James Blunt CB30067-04 1979 Smashing Pumpkins CBE3-24-10 1982 Randy Travis Media Pro 6000-01 1985 Bowling For Soup CB30048-02 1994 Jason Aldean ASK-1303B-07 2 Become 1 Spice Girls Media Pro 6000-01 2 In The Morning New Kids On The Block CB30097-07 2 Reasons Trey Songz ftg. T.I. Media Pro 6000-01 2 Stars Camp Rock DISCMPRCK-07 22 Taylor Swift ASK-1212A-01 23 Mike Will Made It Feat. -

Geographic Implications of the Fiddling Tradition in Oklahoma

GEOGRAPHIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE FIDDLING TRADITION IN OKLAHOMA By JAMES HUBERT RENNER 1/ Bachelor of Science University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon 1974 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1979 ~ /979 7( '-/14q QQp. 2_ c ~W51vfA~ fo+~-- ~)', 0 UNIVERSITY (' LIBRARY GEOGRAPHIC IMPLICATIONS OF THE FIDDLING TRADITION IN OKLAHOMA Thesis Approved: 1,029474- ii PREFACE This thesis is a combination of two longstanding in terests--geography and fiddling. The background and origin of this unique study was fostered by Dr. Everett Smith, my undergraduate advisor at the University of Oregon, who first encouraged me to pursue a course of study which would com bine the two. Following my graduation of Oregon, I journeyed to Penn State University to attend the first meeting of the emergent Society for a North American Cultural Survey (SNAGS) and to meet Dr. George Carney, who had pioneered geographic re search in traditional American music. I later joined the graduate program at Oklahoma State University to work under Carney. While conducting my graduate studies, I received a Youthgrant from the National Endowment for_ the Humanities to establish an Archive of Oklahoma Fiddlers. This project was begun in the summer of 1976 and completed in the fall of 1977. During this same period of time, I was chosen to serve as "Resident Folk Artist" for the Oklahoma Arts and Humanities Council. Both of these experiences provided in valuable experience and information concerning music and culture in Oklahoma which became the foundation of this re search. -

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words

Name Artist Album Track Number Track Count Year Wasted Words Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 1 7 1973 Ramblin' Man Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 2 7 1973 Come and Go Blues Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 3 7 1973 Jelly Jelly Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 4 7 1973 Southbound Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 5 7 1973 Jessica Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 6 7 1973 Pony Boy Allman Brothers Band Brothers and Sisters 7 7 1973 Trouble No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 1 6 1972 Stand Back Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 2 6 1972 One Way Out Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 3 6 1972 Melissa Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 4 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Blue Sky Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 5 6 1972 Ain't Wastin' Time No More Allman Brothers Band Eat A Peach 6 6 1972 Oklahoma Hills Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 1 6 1969 Every Hand in the Land Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 2 6 1969 Coming in to Los Angeles Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 3 6 1969 Stealin' Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 4 6 1969 My Front Pages Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 5 6 1969 Running Down the Road Arlo Guthrie Running Down the Road 6 6 1969 I Believe When I Fall in Love Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 My Little Town Art Garfunkel Breakaway 1 8 1975 Ragdoll Art Garfunkel Breakaway 2 8 1975 Breakaway Art Garfunkel Breakaway 3 8 1975 Disney Girls Art Garfunkel Breakaway 4 8 1975 Waters of March Art Garfunkel Breakaway 5 8 1975 I Only Have Eyes for You Art Garfunkel Breakaway 7 8 1975 Lookin' for the Right One Art Garfunkel Breakaway 8 8 1975 My Maria B. -

New Skye Song List

New Skye Song List Americana Country Acony Bell Gillian Welch Act Naturally Buck Owens Across The Great Divide Kate Wolf Already Gone Eagles Blue and Lonesome Bill Monroe Amie Pure Prairie League Caleb Meyer Gillian Welch Boot Scooting Boogie Brooks & Dunn Crying Madison Violet Cold Day in July Suzy Bogguss Down by the River Neil Young Country Roads John Denver Further in the Hole Claire Lynch Crazy Patsy Cline Give Yourself to Love Kate Wolf Driving My Life Away Eddie Rabbit Harvest Moon Neil Young Family Tradition Hank Williams II High Sierra Trio Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash I Ain't Broke David Grisman Hey Good Lookin' Hank Williams I'll Fly Away Gillian Welch Hurt Me Bad Patty Loveless I’ll Be Waiting Just for You Junior Sisk Jackson Johnny Cash Man of Constant Sorrow Dan Tyminski Jambalaya Hank Williams Oh, Atlanta Allison Krauss Just Good Ol' Boys Moe & Joe Oklahoma Hills Hank Thompson Just One More George Jones Ophelia The Band Louisiana Saturday Night Mel McDaniel Orphan Girl Gillian Welch Pancho & Lefty Emmylou Harris Rag Mama Rag The Band Peaceful Easy Feeling Eagles Stealin' Arlo Guthrie San Antonio Rose Patsy Cline Tecumseh Valley Nanci Griffith Seminole Wind John Anderson This Land Is Your Land Woody Guthrie Silver Wings Merle Haggard Twilight Linda Williams Six Pack to Go Leon Russell Wagon Wheel Old Crow Med/Show Streets of Bakersfield Dwight Yoakam Wichita Gillian Welch Take It Easy Eagles Willin' Little Feat Tequila Sunrise Eagles You Ain't Going Nowhere Bob Dylan The Bottle Let Me Down Merle Haggard You Are My Sunshine -

Coming Events

News You Can Use From The National Kiko Registry Summer 2014 Here’s what the NKR has to offer! You’ve heard the expression that “Bigger is Better!” That The NKR also hosts a major educational conference is especially true when it comes to your Kiko registry. and Spotlight Kiko Sale each year that is open to all The National Kiko Registry has close to 400 clients, clients. These sales have consistently recorded some which includes the largest herds in the industry. These of the highest prices paid for Kiko breeding stock. are active producers that are raising and registering thousands of new Kikos — most of them DNA-tested This is possible because with its large number of and parentage verified. These breeders offer the largest clients, the NKR has more Kiko breeders consigning pool of Kiko genetics available anywhere. more Kiko goats to its sales. A larger selection of ge- netics means more buyers showing up to potentially When you become a client of the NKR, you gain access make purchases. The NKR also heavily promotes its to a modern Kiko registry. You have a professionally clients and their Kikos through advertising in national managed office available to assist with paperwork, and regional publications, letters and postcards — and walk you through the application process and answer now social media. And when you have more buyers, any questions you may have. DNA tests and registra- demand goes up and so do the prices! tion certificates are processed and delivered in a timely manner. And if you happen to live in Canada, All of the above listed benefits easily explain why the there are no extra fees or hidden costs. -

Way Down Yonder in the Indian Nations, Rode My Pony Cross the Reservation from Oklahoma Hills by Woody Guthrie

Tulsa Law Review Volume 29 Issue 2 Native American Symposia Winter 1993 Way Down Yonder in the Indian Nations, Rode My Pony Cross the Reservation from Oklahoma Hills by Woody Guthrie Kirke Kickingbird Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kirke Kickingbird, Way Down Yonder in the Indian Nations, Rode My Pony Cross the Reservation from Oklahoma Hills by Woody Guthrie, 29 Tulsa L. J. 303 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol29/iss2/14 This Native American Symposia Articles is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kickingbird: Way Down Yonder in the Indian Nations, Rode My Pony Cross the Res "WAY DOWN YONDER IN THE INDIAN NATIONS, RODE MY PONY CROSS THE RESERVATION!" FROM "OKLAHOMA HILLS" BY WOODY GUTHRIE Kirke Kickingbirdt I. INTRODUCTION "Way down yonder in the Indian Nations, rode my pony cross the reservation, in those Oklahoma hills where I was born...." So begins one of the 1,000 songs written by balladeer Woody Guthrie. The In- dian Nations of which he writes are the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chicka- saw, Creek and Seminole. The phrase refers to both the tribes themselves and the lands which they occupy. An observer of the tribal-state conflicts in Oklahoma over the last century might conclude that the song seems to be based primarily on nostalgia rather than on any sense of legal reality. -

“Amarillo by Morning” the Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1

In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. On Billboard magazine’s April 4, 1964, Hot 100 2 list, the “Fab Four” held the top five positions. 28 One notch down at Number 6 was “Suspicion,” 29 by a virtually unknown singer from Amarillo, Texas, named Terry Stafford. The following week “Suspicion” – a song that sounded suspiciously like Elvis Presley using an alias – moved up to Number 3, wedged in between the Beatles’ “Twist and Shout” and “She Loves You.”3 The saga of how a Texas boy met the British Invasion head-on, achieving almost overnight success and a Top-10 hit, is one of triumph and “Amarillo By Morning” disappointment, a reminder of the vagaries The Life and Songs of Terry Stafford 1 that are a fact of life when pursuing a career in Joe W. Specht music. It is also the story of Stafford’s continuing development as a gifted songwriter, a fact too often overlooked when assessing his career. Terry Stafford publicity photo circa 1964. Courtesy Joe W. Specht. In the early months of 1964, on their inaugural tour of North America, the Beatles seemed to be everywhere: appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, making the front cover of Newsweek, and playing for fanatical crowds at sold out concerts in Washington, D.C. and New York City. -

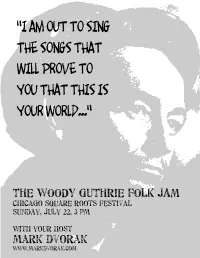

I Am out to Sing the Songs That Will Prove to You That This Is Your World...”

“I AM OUT TO SING THE SONGS THAT WILL PROVE TO YOU THAT THIS IS YOUR WORLD...” THE WOODY GUTHRIE FOLK JAM Chicago Square Roots Festival Sunday, July 22, 3 pm with your host mark dvorak www.markdvorak.com Woody guthrie by STEVE EARLE The Nation, July 21, 2003 When Bob Dylan took the stage at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, all leather and Ray-Bans and Beatle boots, and declared emphatically and (heaven forbid) electrically that he wasn't "gonna work on Maggie's farm no more," the folk music faithful took it personally. They had come to see the scruffy kid with the dusty suede jacket pictured on the covers of Bob Dylan and Freewheelin'. They wanted to hear topical songs. Political songs. Songs like "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll," "Masters of War" and "Blowin' in the Wind." They wanted the heir apparent. The Dauphin. They wanted Woody Guthrie. Dylan wasn't goin' for it. He struggled through two electric numbers before he and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band retreated backstage. After a few minutes he returned alone and, armed with only an acoustic guitar, delivered a scathing "It's All Over Now, Baby Blue" and walked. Woody Guthrie himself had long since been silenced by Huntington's chorea, a hereditary brain-wasting disease, leaving a hole in the heart of American music that would never be filled, and Dylan may have been the only person present at Newport that day with sense enough to know it. One does not become Woody Guthrie by design. Dylan knew that because he had tried.