Change Through Communities: Lessons from District Bureaucrats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District – Nuh

Containment Plan for Large Outbreaks Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) District – Nuh Micro-plan for Containing Local Outbreak of COVID-19 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background On 31st December 2019, World Health Organization (WHO) China Country office was informed of cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology detected in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China. On 7th January 2020, Chinese authorities identified a new strain of Corona virus as causative agent for disease. The virus has been renamed by WHO as SARS-CoV-2 and the disease caused by it as COVID-19. In India, as on 26th February, 2020 three travel related cases were reported (all from Kerala). These three were quarantined and symptomatic treatment provided to all three until five samples turned negative. On 2nd March 2020 two more passengers from Italy and Dubai respectively tested positive for COVID-19. 1.2 Risk Assessment COVID-19 was declared a pandemic by WHO on 11th March, 2020. While earlier the focus of spread was centered on China, it has now shifted to Europe and North America. WHO has advised countries to take a whole-of-government, whole- of-society approach, built around a comprehensive strategy to prevent infections, save lives and minimize impact. In India also, clusters have appeared in multiple States, particularly Kerala, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Punjab, Karnataka, Telangana and UT of Ladakh. 211 districts are now reporting COVID-19 cases and the risk of further spread remains very high. 1.3 Epidemiology Coronaviruses belong to a large family of viruses, some causing illness in people and others that circulate among animals, including camels, cats, bats, etc. -

List of All Judicial Officers Hr.Pdf

This list is for general information only and is not for any legal or official use. The list does not depict any seniority position. [Updated upto 17.12.2018] Sr. No. Name Place of PoStiNg 1. Dr. Neelima Shangla Ambala (Presiding Officer, Industrial Tribunal-cum-Labour Court) HR0014 2. Shri Ashok Kumar Palwal HR0018 3. Shri Sant Parkash Rohtak HR0019 4. Ms. Meenakshi I. Mehta Chandigarh (Legal Remembrancer & Administrative Secretary to Government of Haryana, Law and Legislative Department) HR0022 5. Shri Ajay Kumar Jain Fatehabad HR0023 6. Shri Deepak Gupta Faridabad HR0025 7. Shri Ravi Kumar Sondhi Gurugram HR0026 8. Shri Jagdeep Jain Karnal HR0027 Haryana Judiciary 9. Shri Harnam Singh Thakur Chandigarh Registrar General, Pb. & Hry. High Court HR0028 10. Ms. Ritu Tagore Kurukshetra HR0029 11. Shri A.S. Narang Jind HR0030 12. Shri Kamal Kant Jhajjar HR0033 13. Dr. Sarita Gupta Panipat (Presiding Officer, Industrial Tribunal-cum-Labour Court) HR0034 14. Ms. Manisha Batra Panipat HR0036 15. Shri Vikram Aggarwal Ambala HR0037 16. Shri Arun Kumar Singal Hisar HR0038 17. Shri Baljeet Singh Sonepat (Principal Judge, Family Court) HR0039 Haryana Judiciary 18. Shri Parmod Goyal Panchkula (Member Secretary, Haryana State Legal Services Authority) HR0041 19. Shri Man Mohan Dhonchak Kaithal HR0043 20. Ms. Bimlesh Tanwar Jagadhri HR0044 21. Ms. Shalini Singh Nagpal Chandigarh Director(Administration), Chandigarh Judicial Academy HR0045 22. Shri Subhas Mehla Panchkula HR0047 23. Shri Surya Partap Singh New Delhi (Registrar, Supreme Court of India) HR0048 24. Dr. Ram Niwas Bharti Sirsa HR0050 25. Shri Puneesh Jindia Rohtak Presiding Officer, Industrial Tribunal-cum-Labour Court, Rohtak with addl. -

E55a Oil & Gas

a E55A OIL & GAS Essar Oil Limited Date :28.03.2016 Divisional Office SCO, Plot No. - 9, 1st Floor, New Colony Mor, Old Rly. Road, Ref. No.: Haryana/ NOC/Ujina/WL Gurgaon -'122001, Haryana To, Corporate ldentity Number: 1111 00GJl 989P1C03211 6 The Officer ln charge T +91 124 651 4999 email: eolmarketing@essar conr Wild Life Department www essaroil co in Mewat (Haryana) Subject: "NOC for use of forest land for installation of proposed Retail Outlet/ Petrol Pump in Diversion of forest land 0.0152 Hac. for access to the Proposed Petrol Pump of Essar Oil Ltd. Along at KM Stone No 32 (RHS) Chainage 32.889 at Khewat No. 1234, Khatauni No. 1410, Kila No. L24ll23l8-Ol,t39ll3(7-13), Village - Ujina, on Hodel-Nuh Road (RHS), Tehsil- Nuh, District - Mewat, Haryana ." Dear Sir, We propose to install new Retail Outlet/ Petrol Pump in Diversion of forest land 0.0152 Hac. for access to the Proposed Petrol Pump of Essar Oil Ltd. Along at KM Stone No 32 (RHS) Chainage 32.889 at Khewat No. 1234, Khatauni No. 1410, Kila No. I24/123(8-0\, I39/13(7-L3), Village - Ujina, on Hodel-Nuh Road (RHS), Tehsil - Nuh, District - Mewat, Haryana as per enclosed layout plan. This is to apprise you that there is no animal/ Bird Sanctuary is existing in the above identified site. Also there is no danger to the fauna so hereby we request you to kindly arrange to issue NOC for the proposed Retail Outlet/ Petrol Pump on the site under reference. Copy of layout plan of above mentioned site, is attached for your ready reference. -

ANNUAL REPORT April 2016 - March 31, 2017 Bal Umang Drishya Sanstha (BUDS)

ANNUAL REPORT April 2016 - March 31, 2017 Bal Umang Drishya Sanstha (BUDS) Bal Umang Drishya Sanstha BUDS CORE VALUES (BUDS)LVDUHJLVWHUHGQRQSURÀW • Respects that every organization formed with the child has basic rights to objective of advancing the education, health, nutrition, well being, education, health development and protection and welfare of children in • Promote equitable access India without distinction of • Partners with Government, caste, class, gender, ethnicity, other NGO’s and allied religion, rural/ urban, physical International organization or mental disability. BUDS (QVXUHSURJUDPDQGÀVFDO was established in 2000, and accountability, respect was registered, as an Indian diversity, support community 1RWIRU3URÀW7UXVW self-determination. (Registration No 11686/4 of • Ensure minimal over- ZLWKWKHFRXQWU\RIÀFH head costs. located in New Delhi. • Encourage voluntary participation of professionals BUDS aims is to serve the such as doctors, teachers, underserved children by lawyers, scientists child preventing diseases, promoting rights and social activists. health and providing access to education to every child. REGISTRATION BUDS VISION: envisions a BUDS is registered as an society where every child is in ,QGLDQ1RWIRU3URÀW7UXVW school, free from abuse, neglect, VLQFH 5HJLVWUDWLRQ child labour and poverty. 1RRI BUDS MISSION TAX EXEMPTION D 3URPRWHHYHU\FKLOGLQVFKRRO E 3UHYHQWGLVHDVHDQG All Donation to BUDS are promote early child health exempted U/s 80G (income tax and development, and $FW WD[H[HPSWLRQ F &UHDWHODVWLQJFKDQJH by building healthy community and promote sustainable development. Contact Details BAL UMANG DRISHYA SANSTHA (BUDS) E 10 Green Park Main, New Delhi 110016, India Tel: Email: [email protected] | Website: www.buds.in Bankers Auditors AXIS BANK LTD ALOK MISRA & CO. K 12 Green Park Main, &KDUWHUHG$FFRXQWDQWV New Delhi 110016 1-B, Vikrant Enclave, Mayapuri, New Delhi- 110064 A/C No. -

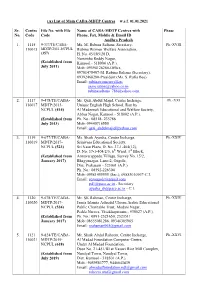

(A) List of Main CABA-MDTP Centres W.E.F. 01.01.2021 Sr. No. Centre Code File No. with File Code Name of CABA-MDTP Centres With

(A) List of Main CABA-MDTP Centres w.e.f. 01.01.2021 Sr. Centre File No. with File Name of CABA-MDTP Centres with Phase No. Code Code Phone, Fax, Mobile & Email ID Andhra Pradesh 1. 1115 9-337/TE/CABA- Ms. M. Rubina Sultana, Secretary, Ph.-XVIII 110015 MDTP/2011-NCPUL Rubina Women Welfare Association, (357) H. No. 45/185/20 D, Narsimha Reddy Nagar, (Established from Kurnool - 518004 (A.P.). July 2011) Mob: 09394126280-Office, 09701478407-M. Rubina Sultana (Secretary), 09392468280-President (Ms. S. Rafia Bee) Email: rubinawomenwelfare [email protected] [email protected] 2. 1117 9-478/TE/CABA- Mr. Qazi Abdul Majid, Centre Incharge, Ph.-XXI 110017 MDTP/2013- Unique English High School, Run by NCPUL (414) Al Madeenah Educational and Welfare Society, Abbas Nagar, Kurnool - 518002 (A.P.). (Established from Ph. No.: 08518- 235786 July 2013) Mob: 09440716555 Email: [email protected] 3. 1119 9-677/TE/CABA- Ms. Shaik Ayesha, Centre Incharge, Ph.-XXIV 110019 MDTP/2017- Srinivasa Educational Society, NCPUL (523) Sri Vasu Plaza, D. No. 37-1-404(12), D. No. 37-1-404/2/5, 6th Ward, 3rd Block, (Established from Annavarappadu Village, Survey No. 15/2, January 2017) Bhagyanagar, Lane-2, Ongole, Dist. Prakasam - 523001 (A.P.) Ph. No.: 08592-226304 Mob: 09581455555 (Sec.), 09885010967-C.I. Email: [email protected] [email protected] - Secretary [email protected] - C.I. 4. 1120 9-678/TE/CABA- Mr. SK Rahman, Centre Incharge, Ph.-XXIV 110020 MDTP/2017- Jamia Islamia Ashraful Uloom Arabic Educational NCPUL (524) Public Charitable Trust, Madani Nagar, Pedda Narava, Visakhapatnam - 530027 (A.P.). -

Nuh) District, Haryana (India

Current World Environment Vol. 11(2), 388-398 (2016) Analysis of Water Level Fluctuations and TDS Variations in the Groundwater at Mewat (Nuh) District, Haryana (India) PRIYANKA1, GOpal KRISHAN2, LALIT MOHAN SHARMA3, BRIJESH KUMAR Yadav4 and N.C. GHOSH2 1TERI University, New Delhi India. 2National Institute of Hydrology, Roorkee, India. 3Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon, India. 4IIT-Roorkee, Roorkee, India. http://dx.doi.org/10.12944/CWE.11.2.06 (Received: July 18, 2016; Accepted: August 02, 2016) ABSTRACT Groundwater is the major source for fulfilling the water needs of domestic and agricultural sectors in Mewat district, Haryana, India and its continuous use has put an enormous pressure on the groundwater resource, which along with low rainfall and variable geographical conditions lead to the declining water levels. The other problem of this area is high salinity which is reported intruding to the freshwater zone1. Taking into account the twin problem of declining water level and high salinity the study was taken up jointly by National Institute of Hydrology, Roorkee; Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon and Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee. Groundwater level and TDS (Total dissolved solids) data for pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons for the time period of 2011–2015 of 40 monitoring wells developed by Sehgal Foundation, Gurgaon was collected and analysed. It has been found that the groundwater level is decreasing in the area while TDS values show inconsistent trends during 2011-15. Further monitoring of the wells is continued to get the more information on water level and TDS which will help in facilitating the researchers in finding out the applicable solutions for the above problems in the Mewat, Haryana. -

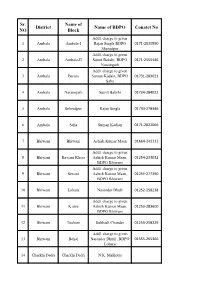

Sr. NO District Name of Block Name of BDPO Conatct No

Sr. Name of District Name of BDPO Conatct No NO Block Addl. charge to given 1 Ambala Ambala-I Rajan Singla BDPO 0171-2530550 Shazadpur Addl. charge to given 2 Ambala Ambala-II Sumit Bakshi, BDPO 0171-2555446 Naraingarh Addl. charge to given 3 Ambala Barara Suman Kadain, BDPO 01731-283021 Saha 4 Ambala Naraingarh Sumit Bakshi 01734-284022 5 Ambala Sehzadpur Rajan Singla 01734-278346 6 Ambala Saha Suman Kadian 0171-2822066 7 Bhiwani Bhiwani Ashish Kumar Maan 01664-242212 Addl. charge to given 8 Bhiwani Bawani Khera Ashish Kumar Maan, 01254-233032 BDPO Bhiwani Addl. charge to given 9 Bhiwani Siwani Ashish Kumar Maan, 01255-277390 BDPO Bhiwani 10 Bhiwani Loharu Narender Dhull 01252-258238 Addl. charge to given 11 Bhiwani K airu Ashish Kumar Maan, 01253-283600 BDPO Bhiwani 12 Bhiwani Tosham Subhash Chander 01253-258229 Addl. charge to given 13 Bhiwani Behal Narender Dhull , BDPO 01555-265366 Loharu 14 Charkhi Dadri Charkhi Dadri N.K. Malhotra Addl. charge to given 15 Charkhi Dadri Bond Narender Singh, BDPO 01252-220071 Charkhi Dadri Addl. charge to given 16 Charkhi Dadri Jhoju Ashok Kumar Chikara, 01250-220053 BDPO Badhra 17 Charkhi Dadri Badhra Jitender Kumar 01252-253295 18 Faridabad Faridabad Pardeep -I (ESM) 0129-4077237 19 Faridabad Ballabgarh Pooja Sharma 0129-2242244 Addl. charge to given 20 Faridabad Tigaon Pardeep-I, BDPO 9991188187/land line not av Faridabad Addl. charge to given 21 Faridabad Prithla Pooja Sharma, BDPO 01275-262386 Ballabgarh 22 Fatehabad Fatehabad Sombir 01667-220018 Addl. charge to given 23 Fatehabad Ratia Ravinder Kumar, BDPO 01697-250052 Bhuna 24 Fatehabad Tohana Narender Singh 01692-230064 Addl. -

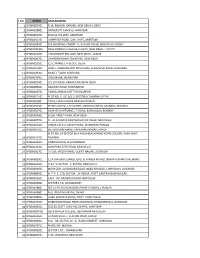

Atms RE CALIBRATED 09.12.2016

S NO ATMID ATM ADDRESS 1 SPSBA007501 E-16, RAJOURI GARDEN, NEW DELHI-110027 2 SPSBA028801 UNIVERSITY,CAMPUS, AMRITSAR 3 SPSBA003101 KHALSA COLLEGE, AMRITSAR 4 SPSBA010201 LAWRENCE ROAD, CIVIL LINES, AMRITSAR 5 SPSBA048701 D-6 SHOPPING CENTRE 11, VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI-110057 6 SPSBA090302 DESH BANDHU COLLEGE, KALKAJI, NEW DELHI - 110 019 7 SPSBA061201 7 SIDHARATH ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI -110014 8 SPSBA000701 CHANDNICHOWK FOUNTAIN, NEW DELHI 9 SPSBA056501 C.S.C MARKET, A-BLOCK, DELHI 10 SPSBA015901 SUNET LUDHIANA OPP MILK PLANT,FEROZEPUR ROAD, LUDHIANA 11 SPSBA029301 MODEL TOWN LUDHIANA 12 SPSBA076401 GTB NAGAR, JALANDHAR 13 SPSBA001901 5/1 D.B.ROAD, PAHAR GANJ,NEW DELHI 14 SPSBA000901 RAILWAY ROAD, HOSHIARPUR 15 SPSBA010701 TANDA URMAR DISTT HOSHIARPUR 16 SPSBA072201 PLOT NO: 2, LSC NO: 3, SECTOR-6, DWARKA, DELHI 17 SPSBA053801 195-B, LOHIA NAGAR NEW GHAZIABAD 18 SPSBA052301 FITWEL HOUSE, L B S MARG, VIKHROLI (WEST), MUMBAI, MUMBAI 19 SPSBA064701 MOHAR APARTMENT,L.T.ROAD, BORIVILI(W), BOMBAY 20 SPSBA087801 B-136, PREET VIHAR, NEW DELHI 21 SPSBA087701 D - 31 ACHARYA NIKETAN,MAYUR VIHAR, NEW DELHI 22 SPSBA061301 URBAN ESTATE GARAH ROAD, JALANDHAR PUNJAB 23 SPSBA087101 B55 GAUTAM MARG, HANUMAN NAGAR, JAIPUR PLOT NO. 14 SECTOR 26-A PALM BEACH ROAD KOPRI COLONY, VASHI NAVI 24 SPSBA046701 MUMBAI 25 SPSBA030001 LINKING ROAD, KHAR BOMBAY 26 SPSBA032301 JANGPURA EXTENTION, NEW DELHI 27 SPSBA091701 3 / 536, VIVEK KHAND, GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW 28 SPSBA088301 12 A JAIPURIA SUNRISE GREEN, AHINSA KHAND, INDIRA PURAM GHAZIABAD 29 SPSBA091201 H-32 / 6 SECTOR - 3, ROHINI, NEW DLEHI 30 SPSBA091601 80/19-20/1 GURDWARA ROAD, NAKA HINDOLA, CHAR BAGH, LUCKNOW 31 SPSBA086501 N. -

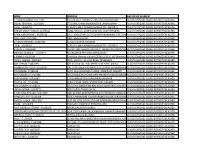

Name Address Nature of Payment P

NAME ADDRESS NATURE OF PAYMENT P. NAVEENKUMAR -91774443 NO 139 KALATHUMEDU STREETMELMANAVOOR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED VISHAL TEKRIWAL -31262196 27,GOPAL CHANDRAMUKHERJEE LANEHOWRAH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED BHIKAM SINGH THAKUR -21445522 JABALPURS/O UDADET SINGHVILL MODH PIPARIYA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ATINAINARLINGAM S -91828130 NO 2 HINDUSTAN LIVER COLONYTHAGARAJAN STREET PAMMAL0CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED USHA DEVI -27227284 VPO - SILOKHARA00 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUSHMA BHENGRA -19404716 A-3/221,SECTOR-23ROHINI CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED LOCAL -16280591 #196 5TH MAIN ROADCHAMRAJPETPH 26679019 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAKESH V -91920908 NO 304 2ND FLOOR,THIRUMALA HOMES 3RD CROSS NGRLAYOUT,CLAIMS CHEQUES ROOPENA ISSUED AGRAHARA, BUT NOT ENCASHED KRISHAN AGARWAL -21454923 R/O RAJAPUR TEH MAUCHITRAKOOT0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED K KUMAR -91623280 2 nd floor.olympic colonyPLOT NO.10,FLAT NO.28annanagarCLAIMS west, CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MOHD. ARMAN -19381845 1571, GALI NO.-39,JOOR BAGH,TRI NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED ANIL VERMA -21442459 S/O MUNNA LAL JIVILL&POST-KOTHRITEH-ASHTA CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAMBHAVAN YADAV -21458700 S/O SURAJ DEEN YADAVR/O VILG GANDHI GANJKARUI CHITRAKOOTCLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD SHADAB -27188338 H.NO-10/242 DAKSHIN PURIDR. AMBEDKAR NAGAR0 CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MD FAROOQUE -31277841 3/H/20 RAJA DINENDRA STREETWARD NO-28,K.M.CNARKELDANGACLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED RAJIV KUMAR -13595687 CONSUMER APPEALCONSUMERCONSUMER CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED MUNNA LAL -27161686 H NO 524036 YARDS, SECTOR 3BALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED SUNIL KUMAR -27220272 S/o GIRRAJ SINGHH.NO-881, RAJIV COLONYBALLABGARH CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED DIKSHA ARORA -19260773 605CELLENO TOWERDLF IV CLAIMS CHEQUES ISSUED BUT NOT ENCASHED R. -

Department of School Education, Government of Haryana List of High and Sr.Sec

Department of School Education, Government of Haryana List of High and Sr.Sec. Schools,Nuh, District Nuh S.No School Type Location Name of DDO Code 1. 868 GSSS Ghasera Wajid Hussain 2. 869 GSSS Chhapera Dheeraj Singh 3. 882 GSSS Indri Mahender Singh 4. 6625 GSSS Nuh Deen Mohd. 5. 804 GSSS Malab Hasan Mohd 6. 705 GSSS Kairaka Changej Khan 7. 802 GSSS Akera Sunil Kumar 8. 706 GSSS Adbar Khalil Ahmed 9. 707 GSSS Sangail Virender 10. 795 GHS Alduka Urmil 11. 796 GSSS Feroz Pur Namak Sudesh Kumar 12. 797 GHS Ujina Jitender Kumar 13. 798 GGSSS Ujina Narender 14. 800 GGSSS Nuh Saddik Ahmed 15. 6055 GSSS Kamarsika Shyam Kumar 16. 801 GHS Meoli Om Parkash 17. 803 GHS Kurthala Raman 18. 808 GSSS Atta Barota Surender Kumar 19. 915 GSSS Gangoli Jahawar Dagar 20. 916 GHS Khera Khalilpur Dharambir 21. 918 GHS Bhiravati Surender 22. 6048 GHS Kotla Ajit Singh 23. 5869 GHS Alawalpur Nawab Khan 24. 814 GSSS Khor Basai Ramesh Kumar 25. 6060 GHS B.B. Pur Vidya Sagart 26. 713 GHS Manuwas Chokh Ram 27. 6031 GHS Tapkan Deepak 28. 948 GSSS Kherla Satvir Kundu 29. 815 GSSS Rewason Desh Raj 30. 6523 GGSSS Ghasera Satish Kumar 31. F.P.Jhirka 818 GSSS Agon Arun Kumar 9728456645 32. 875 GGSSS F.P.Jhirka Inderjeet Singh majoka 9050113597 33. 884 GSSS Ferozpur Jhirka Vishnu Kumar 9971394231 34. 871 GSSS Sakrash Aalamdeen 9416124398 35. 6088 GSSS Raniyala Satish kumar 9896661977 36. 881 GSSS Baded Anil Gautam 9466054202 37. 819 GSSS Biwan Lal Khan 9991507489 38. -

Supplementary DPR Documents

DAKSHIN HARYANA BIJLI VITRAN NIGAM LIMITED SCHEME FOR HOUSEHOLD ELECTRIFICATION DISTRICT : Mewat (HARYANA) (AS PER SUPLEMENTRY DPR) DEEN DAYAL UPADHYAYA GRAM JYOTI YOJANA Table of Contents Sl.No. Format No. Name Page No. 1 A General Information 1 2 A(I) Brief Writeup 2 3 A(II) Minutes 2 4 A(III) Pert Chart 2 5 A(IV) Certificate 2 6 A(V) Basic Details of District 2 7 A(VI) Abstract : Scope of Work & Estimated Cost 4 8 B Electrification of UE villages 10 9 B(I) Block-wise coverage of villages 11 10 B(II) Villagewise/Habitation wise coverage 12 11 B(III) Existing Habitation Wise Infrastructure 12 12 B(IV) Village Wise/Habitation Proposed Works 12 13 B(V) Existing REDB Infrastructure 12 14 B(VI) Block-Wise Substation 13 15 B(VII) Feederwise DTs 14 16 C Feeder Segregation 16 17 D Connecting unconnected RHHs 17 18 D(I) Block-wise coverage of villages 18 19 D(II) Villagewise/Habitation wise coverage 19 20 D(III) Existing Habitation Wise Infrastructure 19 21 D(IV) Village Wise/Habitation Proposed Works 19 22 D(V) Existing REDB Infrastructure 19 23 D(VI) Block-Wise Substation 20 24 D(VII) Feederwise DTs 21 25 E Metering 23 26 E(I) DTR Metering 24 27 E(II) Consumer Metering 40 28 E(III) Shifting of Meters 42 29 E(IV) Feeder Metering 43 30 F System Strengthening and Augmentation 44 31 F(I) Block-Wise Substation 45 32 F(II) EHV Substation Feeding the District 46 33 F(III) Districtwise Details of Existing 11 KV or 22 KV Lines 51 34 G SAGY 53 35 G(I) Block-wise coverage of villages 54 36 G(II) Villagewise/Habitation wise coverage 55 37 G(III) Existing -

Project Report Regional Mapping of Local Governance

Regional Mapping of Local Governance ACROSS HARYANA, RAJASTHAN AND BIHAR IN INDIA (USING COMMUNITY SCORE CARD METHODOLOGY) DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH AND POLICY INITIATIVES S M SEHGAL FOUNDATION (2019) 1 FOREWORD/PREFACE LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents FOREWORD/PREFACE ................................................................................................ 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................................... 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................ 1 LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND ANNEXURES .................................................... 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Sehgal Foundation’s work on Good Rural Governance ....................................... 4 1.2 Project Objectives ................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Accountability in Governance -via citizen participation ...................................... 5 2.0 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................... 8 3.0 results from citizen report card ............................................................................... 10 3.0.1 Survey methodology ........................................................................................ 10 3.1 profile: samastipur district in bihar ........................................................................