Pointe of Departure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020

® 2019-2020 Season Overview JULY 2020 Report Summary The following is a report on the gender distribution of choreographers whose works were presented in the 2019-2020 seasons of the fifty largest ballet companies in the United States. Dance Data Project® separates metrics into subsections based on program, length of works (full-length, mixed bill), stage (main stage, non-main stage), company type (main company, second company), and premiere (non-premiere, world premiere). The final section of the report compares gender distributions from the 2018- 2019 Season Overview to the present findings. Sources, limitations, and company are detailed at the end of the report. Introduction The report contains three sections. Section I details the total distribution of male and female choreographic works for the 2019-2020 (or equivalent) season. It also discusses gender distribution within programs, defined as productions made up of full-length or mixed bill works, and within stage and company types. Section II examines the distribution of male and female-choreographed world premieres for the 2019-2020 season, as well as main stage and non-main stage world premieres. Section III compares the present findings to findings from DDP’s 2018-2019 Season Overview. © DDP 2019 Dance DATA 2019 - 2020 Season Overview Project] Primary Findings 2018-2019 2019-2020 Male Female n/a Male Female Both Programs 70% 4% 26% 62% 8% 30% All Works 81% 17% 2% 72% 26% 2% Full-Length Works 88% 8% 4% 83% 12% 5% Mixed Bill Works 79% 19% 2% 69% 30% 1% World Premieres 65% 34% 1% 55% 44% 1% Please note: This figure appears inSection III of the report. -

A SEASON of Dance Has Always Been About Togetherness

THE SEASON TICKET HOLDER ADVANTAGE — SPECIAL PERKS, JUST FOR YOU JULIE KENT, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR 2020/21 A SEASON OF Dance has always been about togetherness. Now more than ever, we cannot“ wait to share our art with you. – Julie Kent A SEASON OF BEAUTY DELIGHT WONDER NEXTsteps A NIGHT OF RATMANSKY New works by Silas Farley, Dana Genshaft, Fresh, forward works by Alexei Ratmansky and Stanton Welch MARCH 3 – 7, 2021 SEPTEMBER 30 – OCTOBER 4, 2020 The Kennedy Center, Eisenhower Theater The Harman Center for the Arts, Shakespeare Theatre The Washington Ballet is thrilled to present an evening of works The Washington Ballet continues to champion the by Alexei Ratmansky, American Ballet Theatre’s prolific artist-in- advancement and evolution of dance in the 21st century. residence. Known for his musicality, energy, and classicism, the NEXTsteps, The Washington Ballet’s 2020/21 season opener, renowned choreographer is defining what classical ballet looks brings fresh, new ballets created on TWB dancers to the like in the 21st century. In addition to the 17 ballets he’s created nation’s capital. With works by emerging and acclaimed for ABT, Ratmansky has choreographed genre-defining ballets choreographers Silas Farley, dancer and choreographer for the Mariinsky Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the Royal with the New York City Ballet; Dana Genshaft, former San Swedish Ballet, Dutch National Ballet, New York City Ballet, Francisco Ballet soloist and returning TWB choreographer; San Francisco Ballet, The Australian Ballet and more, as well as and Stanton Welch, Artistic Director of the Houston Ballet, for ballet greats Nina Ananiashvili, Diana Vishneva, and Mikhail energy and inspiration will abound from the studio, to the Baryshnikov. -

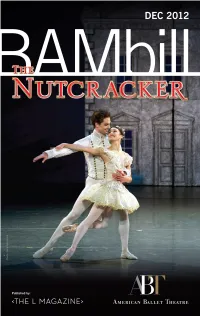

The Nutcracker

American Ballet Theatre Kevin McKenzie Rachel S. Moore Artistic Director Chief Executive Officer Alexei Ratmansky Artist in Residence HERMAN CORNEJO · MARCELO GOMES · DAVID HALLBERG PALOMA HERRERA · JULIE KENT · GILLIAN MURPHY · VERONIKA PART XIOMARA REYES · POLINA SEMIONOVA · HEE SEO · CORY STEARNS STELLA ABRERA · KRISTI BOONE · ISABELLA BOYLSTON · MISTY COPELAND ALEXANDRE HAMMOUDI · YURIKO KAJIYA · SARAH LANE · JARED MATTHEWS SIMONE MESSMER · SASCHA RADETSKY · CRAIG SALSTEIN · DANIIL SIMKIN · JAMES WHITESIDE Alexei Agoudine · Eun Young Ahn · Sterling Baca · Alexandra Basmagy · Gemma Bond · Kelley Boyd Julio Bragado-Young · Skylar Brandt · Puanani Brown · Marian Butler · Nicola Curry · Gray Davis Brittany DeGrofft · Grant DeLong · Roddy Doble · Kenneth Easter · Zhong-Jing Fang · Thomas Forster April Giangeruso · Joseph Gorak · Nicole Graniero · Melanie Hamrick · Blaine Hoven · Mikhail Ilyin Gabrielle Johnson · Jamie Kopit · Vitali Krauchenka · Courtney Lavine · Isadora Loyola · Duncan Lyle Daniel Mantei · Elina Miettinen · Patrick Ogle · Luciana Paris · Renata Pavam · Joseph Phillips · Lauren Post Kelley Potter · Luis Ribagorda · Calvin Royal III · Jessica Saund · Adrienne Schulte · Arron Scott Jose Sebastian · Gabe Stone Shayer · Christine Shevchenko · Sarah Smith* · Sean Stewart · Eric Tamm Devon Teuscher · Cassandra Trenary · Leann Underwood · Karen Uphoff · Luciana Voltolini Paulina Waski · Jennifer Whalen · Katherine Williams · Stephanie Williams · Roman Zhurbin Apprentices Claire Davison · Lindsay Karchin · Kaho Ogawa · Sem Sjouke · Bryn Watkins · Zhiyao Zhang Victor Barbee Associate Artistic Director Ormsby Wilkins Music Director Charles Barker David LaMarche Principal Conductor Conductor Ballet Masters Susan Jones · Irina Kolpakova · Clinton Luckett · Nancy Raffa * 2012 Jennifer Alexander Dancer ABT gratefully acknowledges Avery and Andrew Barth for their sponsorship of the corps de ballet in memory of Laima and Rudolph Barth and in recognition of former ABT corps dancer Carmen Barth. -

Nutcracker 5 Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season ______

2013/2014 5 The Nutcracker Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Three Hundred Eighty-Second Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater as its 55th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffman Michael Vernon, Choreography Philip Ellis, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Design Patrick Mero, Lighting Design The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. ____________ Musical Arts Center Thursday vening,E December Fifth, Seven O’Clock Friday Evening, December Sixth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December Seventh, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December Seventh, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Eighth, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress & Children’s Ballet Mistress The children performing in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music Pre-College Ballet Program. MENAHEM PRESSLER th 90BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION Friday, Dec. 13 8pm | Musical Arts Center | $10 Students $20 Regular The Jacobs School of Music will celebrate the 90th birthday of Distinguished Professor Menahem Pressler with a concert that includes performances by violinist Daniel Hope, cellist David Finckel, pianist Wu Han, the Emerson String Quartet, and the master himself! Chat online with the legendary pianist! Thursday, Dec. 12 | 8pm music.indiana.edu/celebrate-pressler For concert tickets, visit the Musical Arts Center Box Office: (812) 855-7433, or go online to music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. -

Classical Music Learning Guide for Swan Lake

Classical Music Distance Learning Guide Distance Learning Guide This guide is designed to help you: • Introduce the story and artistry of Swan Lake to students. • Introduce students to classical music in a fun an engaging way. Contributors: Vanessa Hope, Director of Community Engagement DeMoya Brown, Community Engagement Manager Table of Contents About Swan Lake Artistic & Production Team………………………………………………………….……….…………...….3 The Swan Lake Story ………………………………………………………………...………………….….4 The Swan Lake Creators………………………………………..……………………...…………………....5 The History of Swan Lake……………………………………………………….…………………………..6 Set Design ……...…………………………………...………………...……………………………………...7 Characters…………………………………………………………………….……………………………….8 Introduction to Classical Music ………………………………………………………………………………………9 Music of Swan Lake …………………………………………………………………………………..10—11 Music Activities………………………………………………………………………………………...12—14 Community Engagement Mission Intrinsic to The Washington Ballet’s mission to bring the joy and artistry of dance to the nation’s capital, our community engagement programs provide a variety of opportunities to connect children and adults of all ages, abilities and backgrounds to the art of dance. We aspire to spark and enhance a love for dance, celebrate our cultural diversity and enrich the lives of our community members. To learn more visit: www.washingtonballet.org The Washington Ballet’s Community Engagement programs are supported by: DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities John Edward Fowler Memorial Foundation Howard and Geraldine Polinger -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

Introduction

THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS THE OLIVE WONG PROJECT PERFORMANCE COSTUME DESIGN RESEARCH GUIDE INTRODUCTION COSTUME DESIGN AND PERFORMANCE WRITTEN AND EDITED BY AILEEN ABERCROMBIE The New York Public Library for the Perform- newspapers, sketches, lithographs, poster art ing Arts, located in Lincoln Center Plaza, is and photo- graphs. In this introduction, I will nestled between four of the most infuential share with you some of Olive’s selections from performing arts buildings in New York City: the NYPL collection. Avery Fisher Hall, Te Metropolitan Opera, the Vivian Beaumont Teater (home to the Lincoln There are typically two ways to discuss cos- Center Teater), and David H. Koch Teater. tume design: “manner of dress” and “the history Te library matches its illustrious location with of costume design”. “Manner of dress” contextu- one of the largest collections of material per- alizes the way people dress in their time period taining to the performing arts in the world. due to environment, gender, position, economic constraints and attitude. Tis is essentially the The library catalogs the history of the perform- anthropological approach to costume design. ing arts through collections acquired by notable Others study “the history of costume design”, photographers, directors, designers, perform- examining the way costume designers interpret ers, composers, and patrons. Here in NYC the the manner of dress in their time period: where so many artists live and work we have the history of the profession and the profession- an opportunity, through the library, to hear als. Tis discussion also talks about costume sound recording of early flms, to see shows designers’ backstory, their process, their that closed on Broadway years ago, and get to relationships and their work. -

Kimberly Cilento, of Middletown, DE Is in Her Third Season with the Washington Ballet After Being a Member of Both Their Studio Company and Trainee Program

Kimberly Cilento, of Middletown, DE is in her third season with The Washington Ballet after being a member of both their Studio Company and Trainee Program. Ms. Cilento began her dance training at the Academy of the Dance in Wilmington, DE under the guidance of Victor Wesley and Arthur Hutchinson. At the age of 12 she began training in Philadelphia, PA, first with Barbara Sandonato at the Sandonato School of Ballet and then at the School of the Pennsylvania Ballet with William DeGregory and Arantxa Ochoa. Ms. Cilento has performed with The Washington Ballet in many programs including: The Nutcracker, Sleepy Hollow, Swan Lake, ALICE (in wonderland), Serenade, Theme and Variations, Giselle (staged by Julie Kent and Victor Barbee), Allegro Brillante, The Dream, Jardin Aux Lilac, Les Sylphide, Romeo and Juliet, The Concert, Company B, Duets, The Sleeping Beauty (staged by Julie Kent and Victor Barbee), Teeming Waltzes, RACECAR, and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue. Prior to this, she performed with the Pennsylvania Ballet’s corps de ballet in George Balanchine’s the Nutcracker and Carnival of the Animals. As a member of The Washington Ballet’s Studio Company she performed in several NEWmovement programs, The Sleeping Beauty (Suite), Juanita y Alicia (excerpts), New Works!, Aladdin, Bolero, and Peter and the Wolf. Ms. Cilento has performed with several area arts organizations including Velocity DC Dance Festival, the In Series, and Post Classical Ensemble. She is a past recipient of an Individual Artist grant from the Delaware Division of the Arts and the Louis Vuitton Scholarship at The Washington Ballet. Ms. Cilento has danced choreography by: Sir Frederick Ashton, George Balanchine, John Cranko, Merce Cunningham, Francesca Dugarte, Michel Fokine, John Heginbotham, Jonathan Jordan, Trey McIntyre, Kirk Peterson, Alexei Ratmansky, Jerome Robbins, Brian Reeder, Antony Tudor, Septime Webre, and Christopher Wheeldon. -

East by Northeast the Kingdom of the Shades (From Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena

2013/2014 La Bayadère Act II | Airs | Donizetti Variations Photo by Paul B. Goode, courtesy of the Paul Taylor Dance Company East by Spring Ballet Northeast Seven Hundred Fourth Program of the 2013-14 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents Spring Ballet: East by Northeast The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Music by Ludwig Minkus Staged by Glenda Lucena Donizetti Variations Choreography by George Balanchine Music by Gaetano Donizetti Staged by Sandra Jennings Airs Choreography by Paul Taylor Music by George Frideric Handel Staged by Constance Dinapoli Michael Vernon, Artistic Director, IU Ballet Theater Stuart Chafetz, Conductor Patrick Mero, Lighting Design _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, March Twenty-Eighth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, March Twenty-Ninth, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, March Twenty-Ninth, Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Kingdom of the Shades (from Act II of “La Bayadère”) Choreography by Marius Petipa Staged by Glenda Lucena Music by Ludwig Minkus Orchestration by John Lanchbery* Lighting Re-created by Patrick Mero Glenda Lucena, Ballet Mistress Violette Verdy, Principals Coach Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Premiere: February 4, 1877 | Imperial Ballet, Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre, St. Petersburg Grand Pas de Deux Nikiya, a temple dancer . Alexandra Hartnett Solor, a warrior. Matthew Rusk Pas de Trois (3/28 and 3/29 mat.) First Solo. Katie Zimmerman Second Solo . Laura Whitby Third -

AM ABT Featured Film Interviewees and Dances FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #ABTonPBS #AmericanMasters American Masters American Ballet Theatre: A History Premieres nationwide Friday, May 15, 2015 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Film Interviewees and Featured Dances Film Interviewees (in alphabetical order) Alicia Alonso , dancer, ABT (1940-1960) Clive Barnes , dance critic, The New York Times (1965-1977); now deceased Mikhail Baryshnikov , principal dancer (1974-1978) & artistic director (1980-1989), ABT (archival) Lucia Chase , founding member & co-director (1945-1980), ABT; now deceased (archival) Misty Copeland , dancer, ABT (2001-present); third African-American female soloist and first in two decades at ABT Herman Cornejo , dancer, ABT (1999-present) Agnes de Mille , choreographer, charter member, ABT; now deceased (archival) Frederic Franklin , stager & guest artist, ABT (1997-2012); dancer; co-founder, Slavenska- Franklin Ballet; founding director, National Ballet of Washington, D.C.; now deceased Marcelo Gomes , dancer, ABT (1997-present) Jennifer Homans , author, Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet; founder and director, The Center for Ballet and the Arts at New York University Susan Jaffe , dancer (1980-2002) & ballet master (2010-2012), -

The Australian Ballet 1 2 Swan Lake Melbourne 23 September– 1 October

THE AUSTRALIAN BALLET 1 2 SWAN LAKE MELBOURNE 23 SEPTEMBER– 1 OCTOBER SYDNEY 2–21 DECEMBER Cover: Dimity Azoury. Photography Justin Rider Above: Leanne Stojmenov. Photography Branco Gaica Luke Ingham and Miwako Kubota. Photography Branco Gaica 4 COPPÉLIA NOTE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dame Peggy van Praagh’s fingerprints are on everything we do at The Australian Ballet. How lucky we are to have been founded by such a visionary woman, and to live with the bounty of her legacy every day. Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in her glorious production of Coppélia, which she created for the company in 1979 with two other magnificent artists: director George Ogilvie and designer Kristian Fredrikson. It was her parting gift to the company and it remains a jewel in the crown of our classical repertoire. Dame Peggy was a renowned Swanilda, and this was her second production of Coppélia. Her first was for the Borovansky Ballet in 1960; it was performed as part of The Australian Ballet’s first season in 1962, and was revived in subsequent years. When Dame Peggy returned to The Australian Ballet from retirement in 1978 she began to prepare this new production, which was to be her last. It is a timeless classic, and I am sure it will be performed well into the company’s future. Dame Peggy and Kristian are no longer with us, but in 2016 we had the great pleasure of welcoming George Ogilvie back to the company to oversee the staging of this production. George and Dame Peggy delved into the original Hoffmann story, layering this production with such depth of character and theatricality. -

Houston Ballet 2014-2015 Annual Report

Annual Report 2014 - 2015 BOARD OF TRUSTEES CHAIRMAN Mr. James M. Jordan PRESIDENT Mrs. Phoebe Tudor SECRETARY Mission Statement Mrs. Margaret Alkek Williams OFFICERS Ms. Leticia Loya, VP – Academy Mr. James M. Nicklos, VP – Finance To inspire a lasting love and appreciation for dance through artistic excellence, Mr. Joseph A. Hafner, Jr., VP – Institutional Giving Mr. Daniel M. McClure, VP – Investments exhilarating performances, innovative choreography and Mrs. Becca Cason Thrash, VP – Special Events Mrs. Donald M. Graubart, VP – Trustee Development superb educational programs MEMBERS-AT-LARGE In furtherance of our mission, we are committed to maintaining and enhancing our status as: Ms. Michelle Baden Mrs. F. T. Barr Mrs. Kristy Junco Bradshaw • A classically trained company with a diverse repertory whose range Mrs. J. Patrick Burk Mrs. Lenore K. Burke includes the classics as well as contemporary works. Mrs. Albert Y. Chao Mr. Jesse H. Jones II Mrs. Henry S. May, Jr. • A company that attracts the world’s best dancers and choreographers Mr. Richard K. McGee and provides them with an environment where they can thrive and Mrs. Michael Mithoff Mr. Michael S. Parmet further develop the art form. Mrs. Carroll Robertson Ray Mr. Karl S. Stern Mr. Nicholas L. Swyka • An international company that is accessible to broad and growing local, Mrs. Allison Thacker national, and international audiences. Mrs. Oscar S. Wyatt, Jr. TRUSTEES • A company with a world-class Academy that provides first rate Mrs. Kristen Andreasen Mrs. Richard E. Fant Hon. Mica Mosbacher Mr. Cecil H. Arnim III Mrs. Claire S. Farley Ms. Beth Muecke instruction for professional dancers and meaningful programs for non- Mrs.